INTRODUCTION

Chronic kidney disease is increasingly more prevalent worldwide. Many options are available for patients who progress to end‑stage kidney disease (ESKD), but a kidney transplant remains the best option for patient survival1. Regarding transplant type, living kidney transplants (LKT) have advantages over those performed with deceased donors2,3, such as longer graft survival, lower ischemia time, better HLA match, as well as the possibility for preemptive transplant and decreased waiting time on the transplantation list. Furthermore, a faster transplantation allows better control of complications associated with ESKD, such as cardiovascular disease and mineral bone disease, and better patient survival4.

Although it has many advantages, LKT is not always attainable for multiple reasons. The main barrier is the absence of a suitable living donor, especially in families with genetic kidney disease.

Despite donor availability, a meticulous evaluation has to be performed to assess the safety of kidney donation5. Evaluation for kidney donation encompasses multiple clinical aspects5: screening for kidney disease and other chronic diseases that may put donors at risk for CKD after donation, evaluation of immunological compatibility, exclusion of anatomical contraindication for nephrectomy, and careful psychosocial evaluation. Depending on country regulation or center availability, performing ABO HLA incompatible or kidney paired donation may be an option6. Also, country regulation may impose donor‑related transplants, as is the case in our center, where a transplant is performed only between relatives of first, second, third, or fourth‑order and between spouses. For deceased donors, the consent regarding organ donation is attributed to the donor’s family (or their legal representative). In Brazil, donation from non‑heart‑beating donors is not permitted; only after brain death. Living kidney donation also must be made freely with no coercion and not subject to financial benefit, as established by the Istanbul declaration7.

Consequently, a substantial proportion of patients screened for living kidney donation are not accepted as candidates for many reasons8,9. Herein, aiming at identifying primary reasons for donor rejection, we reported our experience regarding acceptance or rejection of living kidney donor candidates at Hospital do Rim (HRim) (São Paulo - Brazil), which is a world leader in kidney transplantation10.

METHODS

Study design and site

This is a retrospective, observational, and descriptive cross‑sectional study carried out at HRim. Data of medical appointments of living kidney donors evaluated at our center between January and December 2020 were included. Hospital do Rim is a high‑volume transplant center in Brazil and worldwide10, where more than 1,000 patients were transplanted in 201511, and LKT is an important part of the transplant program.

Reflecting the national transplant program, most patients are transplanted at HRim from a deceased donor12. In the last year, the percentage of LKT was about 25‑30%. An efficient program is established at the hospital to optimize medical and psychosocial evaluation and necessary laboratory exams or evaluations by other medical specialties

to determine whether potential donors are suitable for LKT10.

Approach for living kidney donation

At HRim, LKD evaluation follows a comprehensive multi‑step approach: a complete medical history and physical examination are performed to exclude any major contraindication on the first appointment. After that, blood collection for ABO, HLA compatibility and crossmatch are performed. In the second appointment, if crossmatch is negative, another subset of exams is requested: general blood test routines including screening for infectious diseases (HIV, HCV, HBV, CMV, syphilis, and Chagas disease), urine exam (24h collection for determining creatinine clearance and proteinuria, as well as urinalysis) and chest X‑ray. If all exams are unremarkable, at the third appointment a contrast abdominal CT scan is requested for kidney anatomical and vascular evaluation. Depending on exam results and medical history, other exams or specialty evaluations may be requested at any time during this process. Also, all donors are screened for neoplasia according to the general population screening programs. Simultaneously, the recipient is screened for suitability for kidney transplantation and maintains his place on the waiting list13.

Established contraindications for LKD at HRIM are the presence of CKD, diabetes mellitus, hypertension with target organ damage or treatment requirement with more than two antihypertensive agents, cardiovascular disease, body mass index (BMI) > 35, young donor age (less than 25 years old), nephrolithiasis (recurrent or bilateral), active neoplasia (or previous history of melanoma, monoclonal gammopathy, testicular, renal, pulmonary, gastrointestinal or breast cancer), active chronic viral infection (HIV, HBV, HCV, and HTLV) and drug abuse. Moreover, at HRim, the donation from sons to parents is not performed. Other relative contraindications are individualized according to the patient’s clinical situation and the risk threshold acceptable for the center13. Donor voluntary withdrawal is available during evaluation and, if requested, a medica excuse not to donate is given.

Brazil has a very robust national and public health system that supports most treatments for chronic kidney disease, such as the dialysis system and the transplant program. The public health system covers all Brazilian citizens, so cost is not a restriction for transplantation.

Variables of interest and Statistical analysis

Reasons for not proceeding with the donation were evaluated and were categorized as medical, surgical, immunological, psychosocial, or other. Descriptive statistics and variable frequency were performed.

RESULTS

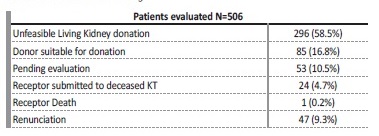

A total of 506 donor‑receptor pairs were enrolled for evaluation during the study period. However, a considerable proportion of patients voluntarily withdrew themselves at variable time points during the evaluation process, a total of 79 (15.6%): 47 not showing up for the initial interview and 32 during ongoing evaluation.

Other reasons for evaluation discontinuation were deceased donor transplantation (N=24, 4.7%) and receptor death (N=1, 0.2%). About 53 (10.5%) of the donor‑receptor pairs are on ongoing evaluation (mainly pending exams, evaluation by other medical specialties or reversible contraindications) and 85 patients (16.8%) were accepted for donor nephrectomy (Table 1).

REASONS FOR DONOR REJECTION - CHARACTERIZATION

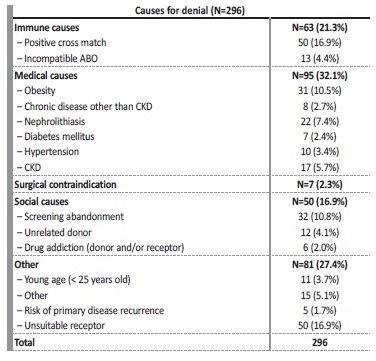

More than half of screened donor‑receptor pairs (N=296, 58.5%) were not considered feasible for LKT. Regarding this group of patients, the reasons for not proceeding to LKT are shown in Table 2. The primary cause for denial was medical contraindication (N=95, 32.1%) followed by immune (N=63, 21.3%) and social (N=50, 19.,3%) causes.

Of note, 17 (5.7%) donors had a positive screening for CKD, either because of abnormal urine sediment or decreased measured creatinine clearance. Surgical causes for denial were related to complex vascular anatomy, mainly the presence of multiple arteries and/or veins and the decision to not procced with donation was always discussed with the surgical team. A total of 50 evaluated pairs were considered infeasible for LKD due to receptor contraindication ascertained during LKD evaluation. Other causes include donor religion precluding blood transfusion, a donation from son to parent (which is not performed at our center) and a prioritized recipient.

DISCUSSION

Living kidney donation is a safe15 procedure, but donor selection and evaluation must be performed in a meticulous way5. Furthermore, studies have shown that the risk of CKD among donors is the same as in the general population but higher than in the healthy population16,17.

Nonetheless, ESKD in kidney donors is extremely rare and usually secondary to preventable causes (such as hypertension or diabetes)15.

As CKD is becoming more prevalent, the gap between the need and availability of organs is increasing, and investment in LKT can aid in diminishing this gap. In addition, an increase in public awareness about living donation is crucial as a significant proportion of patients enrolled in the evaluation of kidney donation voluntarily withdrew or had medical contraindication for LKD, as seen in the data depicted above and in other similar data from centers worldwide8.

Moreover, living donor transplants represent about 30% of all kidney transplants in Brazil, and this rate has decreased over the last 15 years. There is no kidney paired donation program thus all living donations are performed between relatives of first, second, third, or fourth order and between spouses. Although non‑relative donor is allowed, this represents a low percentage of performed kidney transplants (only 7% in 2019, according to the Brazilian Registry of Transplantation)14. Since reports have shown that ESKD in living kidney donors is more frequently related to preventable causes, it is essential to provide them with continuous support in the donation process and during their lifetime after donation5. As such, follow‑up at the transplantation center, general nephrologist, or at a primary care facility with easy access to the transplantation center is fundamental, and a post‑donation care plan should be provided before donation5. Also, prioritizing transplantation for previous donors who evolve to ESKD is another essential practice. Since 2010, previous donors who evolve to end‑stage kidney disease can be prioritized for deceased kidney transplant.

In our center, most patients did not meet the criteria for kidney donation because of medical reasons, similarly to other centers8,18, and this reflects the importance of meticulous donor screening. These medical contraindications relate to metabolic syndrome and related cardiovascular disease (such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, CKD and cardiac and vascular disease). It poses a big challenge for LKT programs as these diseases are increasing worldwide19,20,21 and, in a future perspective, will add further difficulty in kidney donor feasibility.

A possible opportunity for increasing LKT is to target public awareness and educational programs in order to try to diminish the proportion of potential donors that withdraw from the screening process. Further, immune causes constitute a considerable proportion for denial, in which paired donation programs and incompatible ABO transplants could be a possible solution.

Living kidney transplant program and Covid‑19 pandemic

Since 2020, with the Covid‑19 pandemic, health programs were affected in various ways, with living kidney transplants being no exception. Many centers considered LKT as an elective procedure and suspended or reduced it, especially in the first wave of the pandemic, where little was known about the disease impact on transplant patients. Currently we already know that mortality is high among transplanted patients, as much as 25%22,23,24, and procedures were adopted in order to maintain transplantation a safe procedure (at HRim, in addition to clinical screening for respiratory symptoms, pre‑operative nasopharyngeal Covid‑19 PCR as well as thoracic CT scan are performed). Also, patients are instructed to maintain social distancing, mask use and frequent hand cleaning.

Of note, 53 of the enrolled patients (10.5%) (donor or receptor) have pending issues regarding their evaluation; the majority exams or other specialized medical evaluation, which were significantly delayed because of the constraints regarding the Covid‑19 pandemic.

Also, screening abandonment after initial evaluation (donor and receptor) was high (N=32, 10.8%), which may be associated with the pandemic. In addition, HRim evaluates patients from all over Brazil and many restrictive measures adopted have made it difficult for patients to reach the hospital. For instance, the number of internal flights in Brazil was substantially reduced or even canceled in the initial phase of the pandemic.

Adopted measures varied according to the transplant center, although in the beginning, many centers opted for transplant program suspension (LKT or even both living and deceased donor transplant), especially in the first wave, or adapted the transplant program to make the transplant procedure safer. Nowadays we know much more about this disease and although an effective treatment is still not available, many are being researched and many vaccines are on the market. Nonetheless we still do not know the exact efficacy of the vaccine in immunosuppressed patients. Further, the pandemic is still not controlled, especially in countries which have vaccinated a small proportion of citizens only, and there could be several further waves of the epidemic before group immunity is reached. As such, it is essential to adopt measures to ensure safe maintenance of the transplant program from the initial screening of donor/receptor pairs (for instance telemedicine could help) to the transplant procedure itself.

Unfortunately, the number of living kidney transplants dropped drastically in 2020 due to the Covid‑19 pandemic. Therefore, the results from the transplants performed over 2020 cannot represent all livin kidney donations. In 2020, 116 kidney transplants were performed at Hospital do Rim. Among them, the 3‑and 6‑month patient survival was 100%, and the 3‑and 6‑month graft survival was 99.1%.

Our study has some limitations that should be pointed out. First, we used a tertiary source of information without access to medica records, which could introduce some bias, in addition to having a reduced amount of information available. Second, as discussed above, the transplant program was affected by the pandemic in diferente ways. Third, being a single‑center study, some results may not reflect the same reality as other centers in our country. Last, due to cross‑sectional analysis, we could not assess factors associated with the probability of each cause of donation denial. On the other hand, the high number of pairs enrolled in the present study is relevant and these pivotal results may drive further research.

In conclusion, most patients did not meet the criteria for kidney donation due to medical reasons, similarly to other centers, and this reflects the importance of meticulous donor screening.