INTRODUCTION

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) describes a glomerular-injury pattern common to a heterogeneous group of diseases that is further classified based on immunofluorescence staining (IF) and pathophysiological process. It can be mediated by deposition of complemente or immunoglobulin (Ig) either polyclonal or monoclonal.1

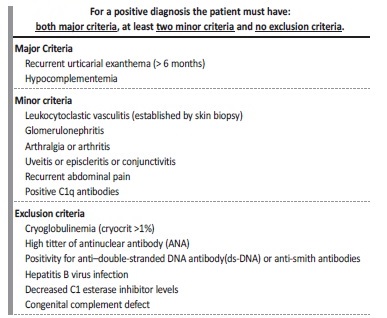

Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome (HUVS) is a rare multiorgan autoimmune disease. It was first described in 1973 by McDuffie et al. based on four patients presenting with recurrent urticarial lesions and hypocomplementemia.2 Later, Schwartz et al. established the diagnostic criteria (shown in Table 1).3-5

Recently, the International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference defined HUVS as an immune complex small-vessel vasculitis accompanied by urticaria and hypocomplementemia, strongly associated with anti-C1q antibodies, introducing the term anti-C1q vasculitis.6

The incidence of HUVS is unknown.5,7 It affects particularly women (female to male ratio of 8:1) in fourth-fifth decade of life.7-9The pathophysiology remains poorly understood, but the presence of IgG antibodies to the Fc portion collagen‑like region of C1q seems to be involved. Activation of the classical complement pathway leads to tissue injury mediated by the membrane attack complex and the influx of inflammatory cells with subsequent mast cell degranulation, chemotaxis of neutrophils and increased vessel permeability resulting in urticaria and/or angioedema.4,5,7

Renal involvement occurs in up to 50% of cases and is usually mild. About 70% of patients presents with variable degrees of proteinuria and/or hematuria. Nonetheless end‑stage renal disease can occur.

Kidney biopsy most commonly show MPGN (35% of cases), but histopathological findings are heterogeneous and may include mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis, membranous nephropathy, crescentic necrotizing vasculitis and minimal change disease.4,8‑10

Since it is a rare disease, there is no consensus on the appropriate treatment. In their recent report, Ion et al analysed 60 out the 92 indentified cases of HUVS on literature. Clinical data and presentation, histopathological findings, therapeutic scheme and final outcome (end stage renal disease and/or death) were all detailed. Based on pathophysiology clinical practice supports the implementation of immunosuppressive therapy. Glucocorticoids are usually the first‑line agent. The association of other agents is generally guided by the clinical presentation. It includes cyclophosphamide with or without plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulin for severe systemic vasculitis or rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis; cyclosporine‑based regimens for nephrotic syndrome and mycophenolate mofetil based regimens for mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis.9,10 Clinical outcome remains unpredictable, but the degree of hypocomplementemia and severity of presentation herald a poor prognosis.4

CASE REPORT

A 40‑year‑old white woman with past medical history of breast lobular carcinoma in situ submitted to radical mastectomy and under tamoxifen since August 2018 was referred by her primary physician to the emergency department for generalized edema, arterial hypertension and asthenia with 6 months of evolution.

Clinical and laboratorial presentation

Upon admission, physical exam was remarkable for pallor, anasarca, grade‑3 arterial hypertension and urticarial rash of the limbs and trunk. Blood tests revealed anemia (hemoglobin 9.1 g/dL), decreased renal function (serum creatinine 1.4 mg/dL, serum urea 48 mg/dL) and altered urinalysis with microscopic hematúria (1182u/L), leukocyturia (183u/L) and proteinuria (>600mg/dL). Considering the cutaneous urticarial rash and renal dysfunction, the patient was admitted.

When questioned, the patient reported long‑lasting paroxysmal episodes (1 to 2 per year) of non‑pruritic and self‑limiting (less than 24 hours) skin papules mainly confined to limbs and trunk, apparently stable until 2018, when she underwent a mastectomy. After this, she developed progressive worsening of skin lesions, which became multiple, itching with increased frequency and duration and essentially described as urticarial plaques. Eight months after, in February of 2019, she presented her first episode of angioedema. A course of antihistamines, corticosteroids and subsequent interruption of tamoxifen (on suspicion of tamoxifen anaphylaxis) were tried, unsuccessfully.

Evolving from there, she additionally started progressive fatigue, arterial hypertension, generalized edema and foamy urine, recurring bi‑tri‑monthly to her physician for at least one of the triad of pitting edema, urticarial skin lesions and/or labial angioedema. Renal function remained stable (serum creatinine 0.79 mg/dL, serum urea 32mg/dL) during this period but presenting 3+ erythro‑proteinuria on urinalysis. She was referred to the emergency department in November 2019.

Diagnostic procedures

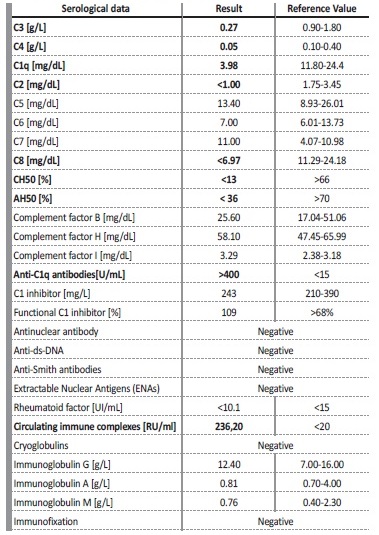

Key laboratory findings confirmed nephrotic syndrome (proteinuria of 8.5 g/day; albumin 19.5 g/L; total cholesterol 203 mg/dL, triglycerides 201 mg/dL); dysmorphic erythrocyturia; elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (79 mm/h); increased sérum levels of circulating immune complexes 236,20 RU/mL ([<20]), hypocomplementemia (C3 0.27 g/dL [0.90‑1.80], C4 0.05g/dL [0.10‑0.40], C1q 3.98 mg / dL [11.80‑24.4], C2 <1,00 mg/dL [1.75‑3.45], CH50 <13%, AH50< 36%), and increased anti‑C1q antibody of >400 U/mL [<15]). Complement factor B, H and I and complement C1 inhibitor levels were normal. Antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti‑ds‑DNA and anti‑Smith antibodies, anti-SS‑A/SS‑B and other Extractable Nuclear Antigens (ENAs), rheumatoid factor, cryoglobulins, anti‑streptolysin.

O titer, anti‑glomerular basement membrane, antineutrophil cytoplasmic and anti‑phospholipase A2 receptor antibodies were all negative. Serum immunofixation was negative

for a monoclonal protein. Blood and urinary cultures, hepatitis B surface antigen, anti‑hepatitis C virus and anti‑HIV 1/2 antibodies were also negative. There were no signs of thrombotic microangiopathy. (Shown in Table 2)

Kidney biopsy

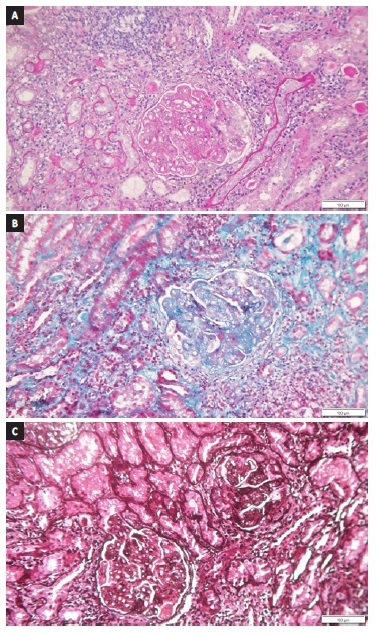

Prior to kidney biopsy, a dermatology consultantation was obtained. An urticarial lesion was sampled and was compatible with leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LV). The kidney biopsy specimen is shown in Figure 1 and 2. A total of 10 glomeruli were obtained. Under light microscopy, glomeruli appeared hyperlobulated, with endocapillary hypercellularity and double contour formation. There were exuberant subendothelial deposits and thrombi and one glomeruli showed cellular crescent.

Figure 1 (a) PAS, (b) methenamine silver and (c) masson trichrome x 160 - Hyperlobulated glomeruli with endocapillary hypercellularity, double contour formation, exuberant subendothelial deposits and thrombi and cellular crescent. Mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate on peri-glomerular interstitium. Droplets of protein reabsorption on the cytoplasm of proximal tubules and tubular hematuria.

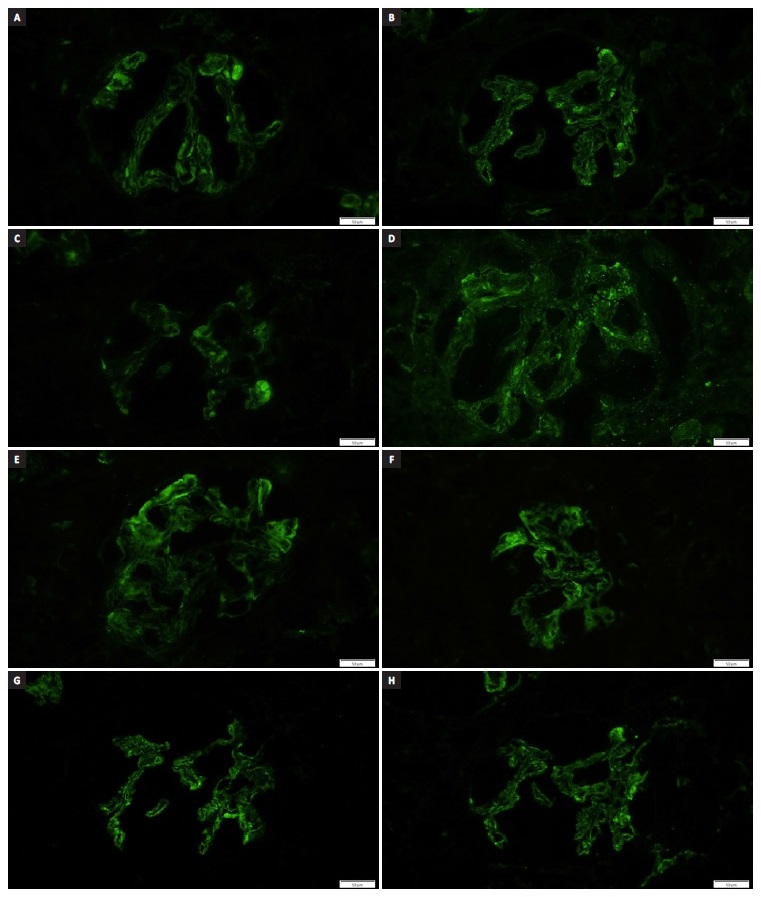

Figure 2 Direct IF - Granular glomerular capillary wall, mesangial and tubulointerstitial (not shown) deposits strongly positive with antisera directed against (a) lambda, (b) kappa, (c) immunoglobulin M, (d) G, (e) A, (f) C4, (g) C3 and (h) C1q.

Thirty percent of the interstitium was occupied by mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate, mainly distributed in the peri‑glomerular region, forming nodules. The cytoplasm of proximal tubules was full of droplets of protein reabsorption. Tubular hematuria was also observed. Direct IF examination of frozen renal tissue demonstrated granular glomerular capillary wall, mesangial and tubulointerstitial deposits strongly positive with antisera directed against immunoglobulin G, A and M, C3, C1q, C4, kappa and lambda.

These findings were consistent with MPGN with a lupus‑like pattern on IF.

Final diagnosis, treatment and follow‑up

On the basis of the presence of 2 major criteria (recurrent urticaria for 6 months and hypocomplementemia) and 3 minor criteria (positive anti‑C1q antibody, cutaneous LV and glomerulonephritis) the diagnosis of HUVS was made.

The patient was treated with 3 daily doses of 1g of methylprednisolone followed by oral prednisolone at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day, mycophenolate mofetil 2 g/day and 200 mg/day of hydroxychloroquine. After discussion with oncology, hormonal therapy with tamoxifen was stopped and replaced by exemestane, an aromatase inhibitor. Shortly after starting immunosuppressive therapy, the urticarial lesions disappeared and her general condition improved.

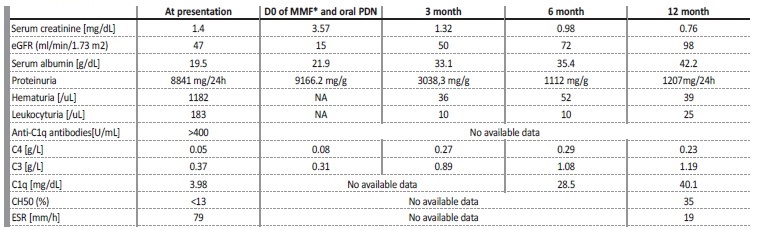

No more episodes of angioedema have been noted. A year after discharge she remained asymptomatic on 5 mg/day of prednisolone and 1.5 g/ day of mycophenolate mofetil. Parallel to clinical stability, creatinine, albumin and proteinuria improved to 0.76 mg/dL (eGFR 98mL/min/1.73 m2), 42.2 g/dL and 1.2 g/day, respectively. Complement levels normalized and stayed stable during follow‑up (shown in Table 3).

DISCUSSION

MPGN is a pattern of glomerular injury that is shared by a heterogeneous number of diseases. Immune‑complex mediated MPGN should lead to evaluation for the presence of an infection, autoimmune disease or a monoclonal gammopathy.1

Our patient presented with skin lesions and nephrotic syndrome due to immune complex mediated MPGN. The diagnosis of HUVS was confirmed, as Schwartz criteria, 2 major (chronic urticarial exanthema and hypocomplementemia) and 3 minor (glomerulonephritis, skin LV and a high anti‑C1q antibody titer), were fulfilled. None of the exclusion criteria were met.9,10

The differential diagnosis between HUVS and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) remains a controversial issue with many authors considering HUVS as a subset of SLE.4,12With regard to renal involvement, these two diseases may actually be indistinguishable.4,7,10 Not infrequently, they share clinical presentation, commonly a combination of hematuria and proteinuria. Furthermore, they may both presente with MPGN pattern and express the full house immunostaining on kidney biopsy, a finding usually reported as highly suggestive of lupus nephritis.11

In contrast, serological findings and skin involvement differentiate HUVS from SLE.4,5Although 50% of HUVS patients have ANAs in their serum, they do not have ds‑DNA or anti‑Smith antibodies.11,12 Other typical HUVS laboratory findings include increased ESR and C‑reactive protein, hypocomplementemia and the presence of anti‑C1q antibodies4,5,7,11 Low C1q (almost invariably present) and low C3 and C4 (that can fluctuate during disease) result from activation of the classical complement pathway and correlate with severity of illness. Anti‑C1q antibodies are present in all cases of active HUVS but they lack specificity and may be also present in 30‑60% of SLE patients.4,5,7,11 Particularities of the anti‑C1q binding to the C1q have been described and may represent a useful tool to differentiate the two diseases in the future.11

Chronic, recurrent, urticarial‑like lesions, lasting longer than 24‑72 hours that resolve with post inflammatory hyperpigmentation are a major diagnostic criterion in HUVS. Biopsy of active skin lesions is the gold standard of diagnosis and should reveal the presence of LV. Direc immunofluorescence of skin biopsy, not done in this case, usually

shows immunoglobulin and complement deposition in blood vessels walls or on endothelium. C1q immunostaining is almost constant in active lesions. If the vasculitis also involves deeper vessels, angioedema may be present. Such deposits also occur together with vasculitis in SLE, but in SLE patients they are typically found along the basal membrane (the SLE band). C1q immunostaining is almost constant in active lesions.5,7,9,11

Other features that may help distinguish HUVS from SLE, are a higher incidence of angioedema (50‑70%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and uveitis (each one, 50%‑60%) in HUVS, all typically absent in SLE.7,12 Our patient presented with angioedema.

Despite the role of anti‑C1q antibodies in HUVS pathogenesis, the disease’s trigger is still a matter of debate.9,11 Viral infections have been described as a possibility, but the data is scarce.11 Analyzing the clinical events in this case, it is not possible to exclude a hormonal trigger for the disease exacerbation, associated to tamoxifen introduction and that is why, after extensive reflection, we decided to suspend it.

Finally, although we believe that HUVS and SLE are different diseases, given the overlapping renal, immune‑mediated, histopathological features, an identical treatment to lupus nephritis was used and complete remission was obtained upon one year of immunosuppressive treatment and replacement of tamoxifen.