INTRODUCTION

The greatest ethical challenge in incorporating palliative care (PC) into medical care is probably to establish PC as early as the diagnosis of chronic illness.

Palliative care is important not only for people with cancer or near death, but also for patients with other chronic incurable disease. While competencies (defined in medicine as a holistic combination of knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes needed to perform specific activities effectively)1 are urgently needed in the field PC, there are few specific education and training opportunities worldwide in PC, and Portugal is no exception.

According to the European Association Palliative Care (EAPC) Guide to Palliative Care Education published in 2015, at the first level

- Palliative Care Approach - all health professionals should be trained in the principles and practices of PC. At the second and third levels

- General Palliative Care and Specialist Palliative Care - expertise should be provided.2

Given the large and growing number of patients with advanced and severe illnesses who require high-quality palliative care, it is critical that the above essential principles and practices of PC be incorporated into the practice of all physicians. Today, several initiatives are promoting the integration of palliative care education, evidence-based assessments, and treatment algorithms into the care of patients in a variety of medical settings.1,2 Efforts to strengthen the PC knowledge and skills of all physicians caring for seriously ill patients through training3 are increasing.

Nephrology is one of the few specialties in which physicians care for the entire duration of the disease, from the earliest stages to the end of the patient’s life. Specialists treat patients in dialysis centers regularly and frequently (weekly or monthly) for many years. In this context, nephrology fosters strong human bonds between physicians and patients.

The scoping review presented here aims to identify the PC competencies that nephrologists should acquire to develop an integrated model of medical care in nephrology.

The competencies of palliative care for nephrologists are mapped in the Scoping Review (SR) providing a basis to validate from the PC competencies identified in the theoretical study those that are applicable in practise in Portugal.

METHODS

This study is based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI ) method for scoping reviews.4

Review question

The review aims to answer the two specific questions:

(i) What are the PC core competencies required for nephrologists?

(ii) What specific competencies are required for nephrologists in each core competency of PC care?

Search strategy

In this review, we used the PCC strategy to formulate the questions:

“P” for Population, “C” for Concept, and “Co” for Context. By aligning the aim of the study with the PCC strategy, we define the guiding questions as follows: “What PC competencies are required for nephrologists?” and “What specific competencies in each PC care core competence are required for nephrologists?”

“P” was defined as “medical professionals by specialty, ie, nephrologists,

“C” was defined as “clinical competencies,” and “Co” was defined as “palliative care.”

Participants

This scoping review considers studies conducted by or aimed at nephrologists and physicians with generalist palliative care expertise. Concept PC clinical competencies.

Context

Studies in the context of broad palliative care.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We applied broad inclusion criteria to cover most topics on clinical competencies required for PC in nephrology, including emerging ones. The inclusion criteria include articles related to specific competencies relevant to nephrology and to general PC that are also applicable to nephrology.

The scoping review includes both quantitative and qualitative studies and grey literature, case studies, and descriptive/review articles/ reviews.

Publications in English, French, Portuguese, and Spanish were included in the abstract review.

In addition, we did not limit the search by year of publication. Excluded from the review were: (i) unpublished studies, reports, expert

opinions, conference proceedings, and letters to the editor; (ii) publications for which the full text was not available; and (iii) studies for which the competencies were paediatric-focused or reflected the opinions of patients or family members.

Types of Sources

Quantitative, qualitative, mixed method studies, review articles and systemic reviews.

All identified keywords and index terms were entered into PubMed and CINAHL, where they were combined with the Boolean operators OR /AND. For databases using CINAHL and PubMed, MeSH terms, and equivalent in the CINAHL, were used.

Keywords were used as headings in the search, and when necessary, the keywords were adopted as headings. While searching throughout the grey literature databases, the search terms were modified to include only “palliative care competencies”.

With regard to the grey literature, the following search tools were used: (i) web search, (ii) international/national reference sites, and(iii) web-based catalogues and databases.

The search procedure is described in detail in Appendix I so that the study can be replicated in other searches.

Information sources

In December 2019, the following electronic databases were searched: PubMed, CINAHL. Complete (from EBSCO). Grey literature was also included.

All resulting articles were reviewed using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Only published studies were reviewed. Ethics approval was therefore not required.

Study selection

After searching, all identified citations were uploaded to Mendeley v1.19.4 (Mendeley Ltd., Elsevier, The Netherlands). Articles collected in Mendeley were exported to the Rayyan QCRI

- Qatar Computing Research Institute web application. Duplicate articles have been removed. After, we begun the initial screening of abstracts and titles using a semi-automated process while providinga high level of usability.

The selection of articles to be included followed a two-step procedure. First, we reviewed all titles and abstracts found through the specified search for eligibility based on the above inclusion and exclusion criteria. In a second step, we evaluated all articles that were deemed relevant in the first review and articles whose abstracts did not contain enough information to make an informed decision. Articles that met the inclusion criteria of this second full-text search were included in the review. Reviews were conducted by two independent investigators.

Data extraction

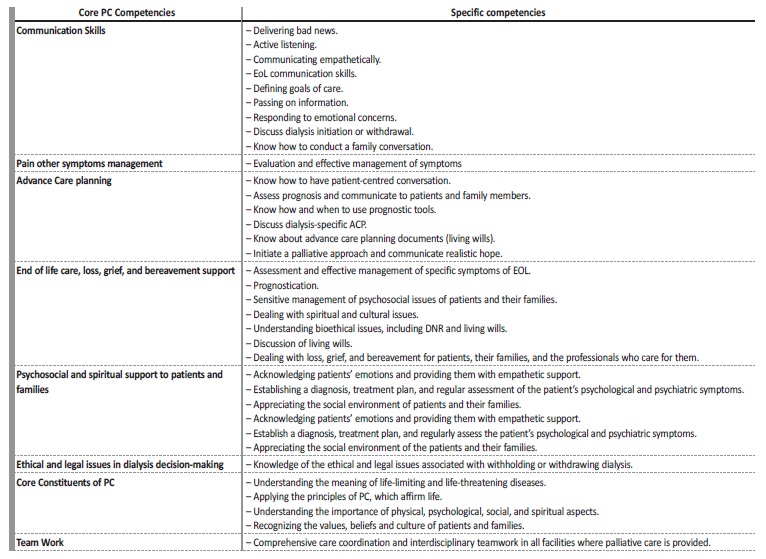

Quantitative and qualitative data were extracted from papers in the review, considering the review questions (Table 1).

Data presentation

Data extracted from the selected papers, were input into Microsoft Excel (Redmond, Washington, USA) worksheets.

One author selected the data and in case of doubt a second author was involved in the decision.

RESULTS

Study inclusion

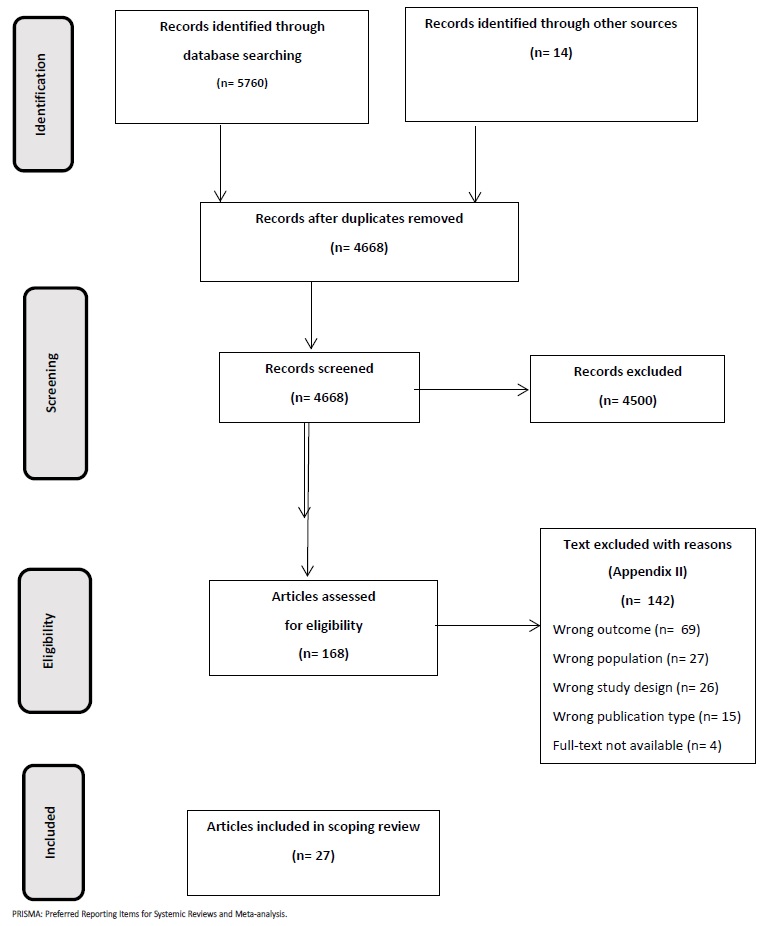

After removing duplicate publications (n= 1092), 4668 citations were identified for study selection.

A total of 168 references met the inclusion criteria based on titles and abstracts, and 165 articles were found in full text. Of these, 142 papers were excluded; the reasons for exclusion are listed in Appendix II. Finally, 27 studies met the inclusion criteria and were evaluated.

The stages of the scoping review process are shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1). In Appendix II the articles ineligible following the full text review are recor.

Characteristics of included studies

All articles selected for this review were published between 1999 and 2018, with 48.1% (n=13) published in the last 10 years. Eighty-five percent (n=23) were published as journal articles, mainly review articles, and 15% (n=4) were published as grey literature. Most participants in the studies were nephrologists (56.8%). Of the 27 studies, 14 were conducted in the United States,5,16 3 in the United Kingdom,17-19 2 in Canada,20,21 1 in Switzerland,22 and 1 in Spain.23

In the grey literature, 5 documents were found, of which 1 was conducted in the United Kingdom,24 2 in Canada,25,26 1 in Belgium27 and 1 in Ireland.28

Appendix III summarises the 22 articles identified in journal articles and Appendix IV summarises the 5 documents identified in grey literature, including: (i) sample data, (ii) participants, (iii) palliative care core competencies, (iv) specific PC competencies in each core competence and (v) main outcome.

Review findings

Fourteen studies included participants exclusively from the field of nephrology.6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,17,19,23,29-31The other thirteen articles and documents involved primary care professionals and specialists treating patients with life-threatening illnesses for which general palliative care skills are required.2,5,15,16,18,20,22,24,26,27,28,32,33

The core competencies found in the literature were grouped into the following eight areas during the scoping review: (i) Communication issues; (ii) Advance care planning; (iii) Pain and other symptom management in renal patients; (iv) Psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families; (v) End-of-life care, loss, grief and bereavement support; (vi) Ethical and legal issues in dialysis decision making (withholding or withdrawing dialysis); (vii) Core components of PC (viii) Teamwork.

Regarding question 1 of the review - What are the core competencies required for nephrologists in palliative care? the following core competencies were identified as most important in the different articles (i) communication skills (21.3%), (ii) EoL care (18.6%), (iii) pain and other symptom control (16%), (iv) advance care planning (16%), (v) ethical and legal issues in dialysis decision making (12.2). Other core competencies such as psychosocial and spiritual support for patients and families were identified as necessary in 5.6% of studies, the core components of PC in the environment of patients and their families in 3.7%, and finally teamwork in 6.6%.

Regarding question 2 - What specific competencies are required of nephrologists in each area of PC? are presented in Table 1.

The specific competencies are presented in most of the studies and are often transversal to the different main areas of PC, showing the connection between the different core competencies. For this reason, we decided not to quantify them in percentage for each study.

DISCUSSION

In our scoping review, we noted that much of the literature on PC focuses on non-nephrology PC, whereas nephrology has specific characteristics that require unique or adapted PC. Indeed, some of the competencies that apply to non-oncologic conditions need to be adapted to the field of nephrology. It should be noted that most of the literature in the field of nephrology PC comes from the USA and Canada. Work in this field began 20 years ago, so it has a considerable degree of maturity.

The following section identifies the specific competencies of PC in nephrology (communication skills, end-of-life care, symptom management, advance care planning, ethical and legal issues in dialysis decision making, other competencies) and justifies their need in this area.

Communication skills

In our review, the number of publications found in the literature on communication skills in nephrology (NCS) has the highest proportion (21.3%) compared to other skills, suggesting that NCS is the fundamental pillar for all core competencies in nephrology. This also reflects the greater importance of communication skills in nephrology compared with other non-oncology conditions. For example, prognostication, which is critical for patients, is much more difficult or impossible. This stems from the fact that kidney disease can take a variety of courses, making prognosis often difficult or unpredictable.

In contrast, for most oncologic diseases, a single course is the most likely scenario.

Another difficult and sensitive topic in nephrology is talking with elderly and frail patients about forgoing or discontinuing dialysis. Most nephrologists do not address this issue because they do not have appropriate communication skills. To face this challenging conversation, clinicians must (i) understand the patient’s disease course and associated comorbidities; (ii) acquire effective communication skills, including inquiring about individual communication and treatment preferences, listening, and tailoring information about prognosis and treatment options to the patient; and (iii) be able to deliver bad news as well as other difficult topics that arise in the end-of-life phase.

Many models have been recommended to identify patients who need a conversation about serious illness. To identify such patients in nephrology, the so-called surprise question (“ Would you be surprised if this patient died within the next year? “) is used effectively.

The identification of critically ill patients is a wake-up call for nephrologists to stimulate the necessary actions to achieve the goals of care discussions. These should be initiated immediately after the patient is identified, as cognitive and functional decline can be extremely rapid in elderly and frail dialysis patients.34

End of Life Care, loss, grief, and bereavement

In our scoping review, EoL care, loss, grief, and bereavement appear second in importance at 18.6%. Lack of planning ahead may justify this high percentage. No advance planning means missed opportunities for symptom control, inadequate support for patients and families, and, in some cases, unintended hospitalizations.28 ESKD is usually characterized by rapid onset (two to three months before death), an increase in symptoms, and a worsening of functional status.35,36

According to the United States (US), published data37 have shown that more than 4/5 of ESKD patients are hospitalized in the last three months of life; approximately 63% are admitted to the intensive care unit. The number of ICU admissions in the last ninety days of life has increased over the last fifteen years.

At different stages of kidney disease, nephrologists should refocus treatment goals. This includes conversations that focus on patient wellness rather than cure while minimizing potentially harmful interventions.

We need to ensure that treatment options and end-of-life care are discussed as kidney disease progresses. Subsequently, these discussions need to resume once patients begin dialysis and then be updated periodically.

Unfortunately, data measuring end-of-life care and hospice utilization in the ESKD population show that patients are not receiving the palliative care expertise they need in most cases.38,39

This is largely due to (i) lack of access to outpatient palliative care services and global palliative care workforce shortages; (ii) inadequate palliative care recognition of the needs of patients with progressive renal failure and ESKD; (iii) deficits in nephrologists’ knowledge and skills in palliative care, which in turn are due to a lack of palliative care training in nephrologist curricula.40

Family support is also an important component of palliative care.

Axelsson et al38 found that less than half of patients’ families received bereavement support (at the medical facility where the patient died) during the dying phase. Importantly, close relatives may also need reassurance and closure with dialysis staff they know well after prolonged dialysis treatment, independent of discussions with staff at the patient’s place of death.41 Therefore, the dialysis clinic team should contact the next of kin independently of other bereavement care.

Pain and Symptom Management

Knowledge of basic kidney disease symptoms is a key component of nephrology PC, as shown in our review with a 16% rate. Symptoms fall into three main categories: renal physical symptoms, non-renal physical symptoms, and psychological/spiritual symptoms. Quality care requires consideration of all aspects of the patient’s symptoms, including non-renal physical symptoms and emotional and spiritual distress.

The symptom burden of dialysis patients can be comparable to that of cancer patients.42 Studies show that the severity of symptoms in CKD and ESKD patients is underestimated and usually not treated.43-45 Particularly severe and worrisome symptoms include fatigue, bone/joint pain, depression, sleep disturbances, uremic pruritus (itching), and restless legs syndrome.44 Some of these symptoms (fatigue and bone/joint pain) affect more than 50% of patients.46

Treatment of pain in renal patients is more difficult due to renal excretion of some opioid metabolites and the development of opioid neurotoxicity.47

This tremendous distress may be one of the reasons for dialysis withdrawal, with rates as high as 35% in the oldest groups.48 Studies show that nephrologists and other health care providers are largely unaware of the presence and severity of symptoms in hemodialysis patients suffering from depression and anxiety.49 This situation contributes to the burden of kidney disease.

Advance care planning

Advance care planning is a communication process that helps adults of any age or health status understand and communicate their personal values, life goals, and preferences to ensure future medical care.

The goal of advance care planning is to ensure that people with serious and chronic illnesses receive medical care that is consistent with their values, goals, and preferences, even when they are no longer able to make decisions for themselves.

The literature reports that few CKD patients participate in advance care planning and that most do not have a written advance directive or surrogate decision maker, leaving them unprepared to make medical decisions in an emergency situation.50,51,52Because the risk of cognitive decline is high among dialysis patients, many are unable to speak for themselves if their condition worsens.

The lack of advance care planning plunges patients, families, and providers into avoidable crises that often result in families opting for aggressive and burdensome care that the patient may not have wanted.

For CKD patients, there is a special need for advance planning because they rely on life-sustaining treatments to survive. In approximately 25% of these patients, death is preceded by a decision to discontinue dialysis.53,54

In our review, the proportion of advance care planning was 16%, as was the proportion of pain and other symptom control.

Ethical and legal issues in dialysis decision-making

Today’s ESKD patients have changed dramatically over the past sixty years. The age of dialysis patients has increased tremendously, as have comorbidities that affect cognition, including dementia.

In this scenario, decision making regarding dialysis initiation, withholding, and discontinuation is complex and should ideally occur within the context of a therapeutic relationship between patient and practitioner with early family involvement. However, decisions are often made in situations where patient´s cognitive abilities are inadequate.

Nephrologists should be aware of and promote the early implementation of advance directives if patients lose their decision-making capacity, so that the patient’s right to autonomous decision-making is preserved.

According to our review, the above competencies account for 12.2% of the selected publications.

Other competencies

Other competencies not mentioned above are the ability to apply:(i) the core components of PC in the setting of patients and their families and (ii) a holistic approach that includes psychological, social, spiritual, religious and existential aspects of care; (iii) teamwork. Surprisingly, in our review, we found that the above core competencies are addressed throughout the non-nephrology literature, but not in the specific nephrology literature, even though they are so important to this field. The first competence (i) appears throughout the non-nephrology literature as a separate field, whereas in the nephrology publications it is distributed among the other specialties, where it is clearly visible. The second competence (ii) is most important in nephrology because of the characteristics of ESKD: it is a chronic and debilitating disease in which renal failure requires an artificial method of excretion to survive. Patients with ESKD must accept various lifestyle, dietary, and hydration restrictions to manage their disease. These restrictions affect patients’ beliefs about the disease and their sense of personal control, leading to anxiety and depression.55 In addition, the loss of freedom associated with dialysistreatment alters marital, family, and social relationships.

This review has some strengths and limitations.

Although we identified many relevant keywords to guide our search, we may have overlooked articles that used other keywords.

In addition, we chose to focus our review on palliative care competencies broadly, without specifying the competencies in question.

This may have limited the breadth of content areas we would have liked to examine (e.g., symptom management). Finally, in accordance with the principles of scoping reviews, we did not exclude articles based on their methodological quality or critically appraise studies based on the quality of the methods used, which not only allowed us to explore the literature more broadly but also may have resulted in the inclusion of some poor-quality studies in our analysis.

CONCLUSION

The review presented here is based on international literature selected using several criteria to capture competencies relevant to nephrology in PC. The review demonstrates the progress of research in geriatric and PC nephrology in recent years and points to the urgent need to introduce PC competencies into nephrology practice. To achieve this goal, it is of utmost importance to include the core competencies PC as an integral part of nephrology training.

The future of this type of integrated care will be based on the principles and practices of PC in the various areas of nephrology: Hemodialysis, Peritoneal Dialysis, Kidney Transplantation. It also addresses CKD patients for whom conservative treatment is most appropriate and end-of-life patients.

Great emphasis should be placed on informing and raising awareness among policy makers and opinion leaders about the benefits of palliative care to alleviate the suffering of patients and their families, promote dignity, and uphold human rights.

To achieve these goals, it is essential that education in PC be introduced during nephrology residency training.

The National Boards of Palliative Medicine and Nephrology must convince the Colégio da Especialidade de Nefrologia and the Ordem dos Médicos to include PC as a mandatory subject in the undergraduate and postgraduate nephrology curriculum.