INTRODUCTION

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is an important cause of hospitalization, morbidity and mortality, being responsible for an important fraction of health expenses.1-2 This entity comprises uncomplicated cystitis, uncomplicated pyelonephritis, asymptomatic bacteriuria and complicated UTI.2 The latter by definition is an UTI with increased risk of complications and treatment failure and is thereby associated with worse prognosis. The main risk factors for complicated UTI are male gender, pregnancy, urine flow obstruction, functional abnormalities such as neurogenic bladder and vesicoureteral reflux, foreign bodies, immunosuppression and diabetes mellitus.1-2 Treatment usually comprises antibiotic therapy, however several complications, such as renal abscesses and xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis, may require more aggressive measures and even nephrectomy.2

Schistosomiasis is a parasitic disease usually acquired through contact of skin or mucocutaneous membranes with contaminated waters, allowing the entry of Schistosoma cercariae. These then migrate through lymphatics and blood vessels into the perivesical or portal venous system where they mature. Females lay eggs in the vesical or intestinal mucosa are expelled in the urine or faeces. Infection typically occurs in teen years, however it’s complications may spread through the fourth or fifth decades. The most common species capable of infecting humans are Schistosoma haematobium, Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum. Usually S. haematobium affects the urinary tract and S. mansoni and S. japonicum usually affect the colon, rectum and liver, but all three can cause metastatic lesions in other organs.2-4 Genitourinary Schistosomiasis is usually diagnosed by analysing a fresh urine sample for ova, although serologic tests may be used in the absence of ova or for evaluating treatment response and there is also the option of polymerase chain reaction assay for S. hematobium in the serum however, its costs limits its use. Diagnosis can also be made by identifying: radiologic bladder and seminal vesicle calcification; pseudotubercles, sandy patches with masses, polyps or neoplasms on cystoscopy; or the parasite in the tissue biopsy.2

We present an antibiotic resistant case of pyelonephritis that finally culminated in nephrectomy and revealed the unexpected diagnosis of an underlying Schistosomiasis.

CASE REPORT

A 52-year old black male born in Cabo Verde, but living in Portugal for the past 20 years, presented at the emergency department with pain in the left iliac fossa that irradiated to the lumbar region and cloudy urine for the past two weeks. Clinical examination revealed a positive left Murphy’s punch sign and gross pyuria. Lab work exposed severe microcytic hypochromic anaemia (haemoglobin 4.9 g/dL, ferritin after transfusion 600 ng/mL, transferritin saturation 8%, folates 3.7 ng/mL and vitamin B12 >2000 pg/mL), high inflammatory markers (leucocytosis of 21660/mm3, neutrophylia of 18860/mm3 and C-reactive protein of 54.4 mg/dL), leucoerythrocyturia (500 leucocytes/uL,150 erythrocytes/uL), serum creatinine of 4.33 mg/dL, urea of 93 mg/dL and metabolic acidosis. Abdominal X-ray displayed a heterogeneous calcified mass over the left renal shadow and echography showed diffuse parietal thickening of the bladder with diverticula, a small left kidney (9 cm of diameter) with numerous calcifications and slightly increased echogenicity of the right renal parenchyma.

Past medical history review revealed altered kidney function since 2001 (20 years earlier), with last serum creatinine from 2 years ago of 2.55 mg/dL, as well as positive interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) without overt tuberculosis, several episodes of renal colic and pyelonephritis.

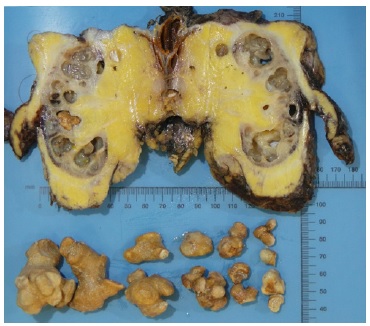

To clarify the imagiological findings, a computed tomography (CT) scan was ordered. It showed a swollen left kidney with a staghorn calculus and intraparenchymal hypodensities, as well as left lateroaortic adenopathies (Fig. 1).

In what regards cultural specimens, blood cultures were negative, urine cultures were consistently contaminated and urine and blood mycobacterial cultures were also negative. We assumed the presumptive diagnosis of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis and, after a failed trial of large spectrum antibiotics (empiric ceftriaxone switched after 48 hours to meropenem due to persistence of elevated inflammatory markers which was maintained for 10 days), the patient was submitted to left radical nephrectomy with significant clinical improvement in the following days. The kidney function also improved after the procedure to a serum creatinine of 2.9 mg/dL. For multifactorial anaemia control, the patient needed transfusion of five erythrocyte concentrates and was started on erythropoiesis stimulating agent (darbepoetin 80 mcg/week) and folic acid, achieving haemoglobin of 8.5 mg/dL at discharge.

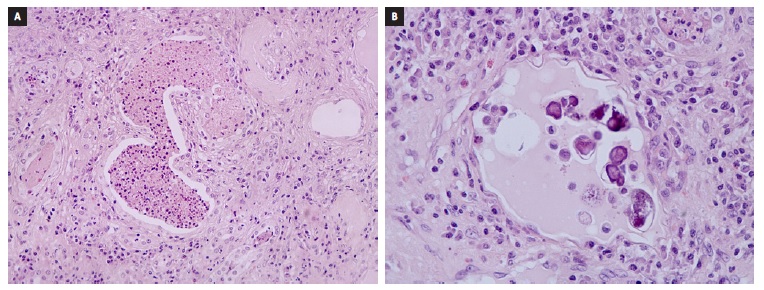

Gross examination showed a markedly dilated pyelocalicial tree, filled with several staghorn calculi and purulent secretions with associated parenchymal atrophy (Fig. 2). Histopathologic evaluation revealed exuberant chronic pyelonephritis with an acute inflammatory infiltrate that extended into the perinephric fat, with areas of necrosis and abscess formation. There were multiple Schistosoma ova, predominantly calcified, along with at least one viable egg. Arterio- and arteriolonephrosclerosis, and atrophy with thyroidisation of tubules, extensive stromal fibrosis and glomerulosclerosis were identified (Fig. 3). In the intraoperative culture specimen it was isolated a multi-sensitive Parvimonas micra.

Given the histological diagnosis of Schistosomiasis, the patient was then given a single dose of praziquantel (40 mg/kg) in order to eradicate any viable parasite and prevent further urinary tract damage.

At follow-up, one year after the initial presentation, the patient had stable kidney function with serum creatinine of 2.4 mg/dL and steady hemoglobin at 11.5 g/dL (without darbepoetin).

DISCUSSION

Although prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions, being especially common in sub-Saharan African migrants, Schistosomiasis is not an endemic disease in Europe, as its distribution throughout the globe is mainly related to its’ secondary host (a specific type of snail - Biomphalaria spp.), demography and poverty.2,4-5 Thus, it is not a usual diagnosis in our clinical practice in Portugal. However, globalization and migration amplified the potential individual and public health effect of this disease.6

Schistosoma nephropathy can be related to: 1) Direct tissue injury with egg deposition in the lower urinary tract in S. haematobium, manifesting as haematuria, pseudotubercles, masses or ulcers and predisposing to nephrolithiasis, UTI and neoplasia (mainly squamous cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder).2-3 Rarely, it can affect the upper urinary tract leading to interstitial chronic nephritis; 2) Effects of immune system to circulating antigens (more commonly associated to S. mansoni), which includes immunecomplex-mediated interstitial chronic nephritis, secondary amyloidosis and immunecomplex-mediated glomerulonephritis.2-3

In this case report, the authors present a severe pyelonephritis in a male patient from Cabo Verde with exuberant clinical and imagiological features suggesting xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis and ending in radical nephrectomy with subsequent identification of Schistosoma.

These findings suggest that previous genitourinary Schistosomiasis predisposed to chronic pyelonephritis and subsequent staghorn nephrolithiasis.

Even though antiparasitic treatment with praziquantel may cure early Schistosoma lesions, it is ineffective in fibrotic lesions.2 In this clinical case authors chose to eradicate Schistosoma infection albeit the predominantly chronic lesions, as Schistosoma ova with cuticle and viable visceral structures were identified in the in the removed kidney and in order to preserve the right kidney.

Although uncommon, Schistosomiasis should be considered in cases of recurrent or even antibiotic resistant urinary tract infections.