Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Nascer e Crescer

versão impressa ISSN 0872-0754versão On-line ISSN 2183-9417

Nascer e Crescer vol.29 no.2 Porto jun. 2020

https://doi.org/10.25753/BirthGrowthMJ.v29.i2.18420

ORIGINAL ARTICLES | ARTIGOS ORIGINAIS

Dating violence - knowledge and attitudes of adolescents and evaluation of the effectiveness of a brief intervention in high school students

Violência no namoro - conhecimentos e atitudes dos adolescentes e avaliação da efetividade de uma intervenção breve em alunos do ensino secundário

Sofia Simões FerreiraI, Mafalda OliveiraII, Benedita AguiarIII, Márcia FerreiraI, Raquel GuedesIV, Márcia CordeiroIV, Hugo Braga TavaresIV

I. Department of Pediatrics, Centro Hospitalar Vila Nova de Gaia e Espinho. 4400-129 Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal. sofiaferreira20@gmail.com; marcia.c.ferreira@gmail.com

II. General and Family Medicine Consultation, Unidade de Saúde Familiar de Santo André de Canidelo. 4400-712 Vila Nova de Gaia. Portugal. mafalda.i.s.oliveira@gmail.com

III. Department of Pediatrics, Centro Hospitalar Entre Douro e Vouga. 4520-211 Santa Maria da Feira, Portugal. beneditabaguiar@gmail.com

IV. Adolescent Medicine Unit, Centro Hospitalar Vila Nova de Gaia e Espinho. 4400-129 Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal. raquelguedes@hotmail.com; marcia.cordeiro@chvng.min-saude.pt; hugotavaresmd@gmail.com

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

ABSTRACT

Teen’s inexperience and willingness to please others make them especially susceptible to violent behavior in relationships, which they accept as natural and as displays of affection.

The present study determined the prevalence of dating violence (DV) in a sample of adolescents from a high school in the northern region of Portugal and their knowledge and attitudes about DV, as well as the effectiveness of a brief intervention to empower adolescents to deal with DV.

This longitudinal, interventional study randomly selected adolescents from a high school and divided them into six groups. Three were subject to an intervention focusing DV. Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI) and Attitudes Toward Dating Violence (ADV) surveys were filled out prior to the intervention. ADV survey was repeated by the intervention group after the intervention.

A total of 138 adolescents from regular and professional education were included. Of these, 75.5% resorted to abusive conflict resolution strategies, 33% to severe violence, and 40.6% were victims of severe violence. Males revealed higher emotional, physical, and sexual violence legitimization perpetrated by both genders. Sixty-nine adolescents participated in the intervention, with girls showing a non-significant decrease in sexual violence legitimacy perpetrated by females and boys showing a non-significant decrease in emotional violence legitimacy perpetrated by males.

A high percentage of adolescents used abusive conflict resolution and severe violence strategies. Despite adolescents active participation during the intervention, its impact in decreasing legitimization of DV was lower than expected.

Keywords: adolescent; intervention study; partner abuse

RESUMO

A inexperiência e vontade de agradar ao próximo tornam os adolescentes particularmente suscetíveis a comportamentos violentos nos relacionamentos, aceitando-os como naturais e, muitas vezes, como manifestações de afeto.

Este estudo pretendeu determinar a prevalência de violência no namoro (VN) numa amostra de adolescentes de uma escola secundária da região norte de Portugal e os seus conhecimentos e atitudes sobre VN, assim como a eficácia de uma breve intervenção na capacitação dos adolescentes em lidar com esta problemática.

Tratou-se de um estudo longitudinal, interventivo, em adolescentes de seis turmas escolhidas aleatoriamente, três das quais acolheram uma intervenção sobre VN. Os inquéritos Inventário de Conflitos nos Relacionamentos de Namoro Adolescentes (CADRI) e Escala de Atitudes acerca da Violência no Namoro (EAVN) foram preenchidos antes da intervenção e o último repetido no grupo submetido à intervenção.

Foram incluídos 138 adolescentes do ensino regular e profissional. Os adolescentes revelaram utilizar estratégias de resolução de conflito abusivas em 75,5% dos casos, recorrer a violência severa em 33% dos casos e ser vítimas de violência severa em 40,6% dos casos. O sexo masculino revelou legitimação superior da violência psicológica, física e sexual perpetrada, quer por rapazes, quer por raparigas. Um total de 69 adolescentes participaram na intervenção, registando-se nas raparigas uma diminuição não estatisticamente significativa da legitimação da violência sexual perpetrada por raparigas e nos rapazes uma diminuição não significativa da legitimação da violência física perpetrada por rapazes.

Uma elevada percentagem de adolescentes utilizaram estratégias de resolução de conflitos abusivas e violência severa. Apesar da participação ativa dos adolescentes durante a intervenção, o impacto desta na diminuição da legitimação da VN foi inferior ao esperado.

Palavras-chave: adolescente; intervenção; violência no namoro

Introduction

Dating violence (DV) in adolescence has been the object of growing awareness.1 Although data on the prevalence and effectiveness of intervention strategies are still scarce, a growing number of studies have sought to determine the true impact of this problem on adolescent health, as well as the most effective strategies to prevent it.2-8

DV includes, not only physical violence, but also other not less important forms of violence, as emotional and sexual.9

Physical violence involves the use of physical force to cause pain and physical harm. It includes actions such as pushing, pulling hair, kicking or punching, burning, tightening arms, among others. Psychological/emotional violence, the most frequent form of violence, consists in criticizing, humiliating, and despising through words and/or behaviors. Sexual violence, on the other hand, covers all forms of sexual practice imposition against the assaulted person’s will.

Adolescence is a period of profound change, learning, and growth. The first relationship experiences emerge at this stage and, given adolescent inexperience, they often interpret certain violent behaviors as acts of love, accepting them.

DV often results from transgenerational transmission of violent attitudes in conflict resolution. Many young people witness violence within their families, becoming more susceptible to suffering from and/or reproducing it in their relationships.10

Regarding gender role, population studies suggest that both males and females may be DV aggressors and victims, although these studies have not analysed factors as motivation or intention. Conversely, studies about violence against women show a male predominance regarding frequency, intensity, and impact of violence in relationships.11,12 This difference is prominent in marital relations, probably motivated by women’s economic dependence and the existence of children.11,12 Gender differences are not so conspicuous among younger populations, what may be understood as greater gender equity at this age.11

The following risk factors have been identified for DV: family factors (parental violence), environmental factors (violence and violence tolerance among peers and community), depression, low self-esteem, interpersonal factors (communication skills, past relationship experiences, and relationship duration), and situational or contextual factors (alcohol and/or drug abuse).10-12

DV is becoming an increasingly relevant health problem due to the worrisome frequency of victimization and violence perpetration. Additionally, it has a substantial impact on victims due to physical and mental health implications, often leading to low self-esteem, anxiety, feelings of shame and guilt, social isolation, and depression. In the long term, DV compromises the victim’s personal and professional quality of life.9 At the same time, it is also considered a strong predictor of violence in marital relations.11,13

Although most adolescents disapprove of intimate partner violence, some studies report DV rates as high as 20−50%, 26−46% of which involve physical violence and 3−12% sexual violence.5-7

In Portugal, a study including college students showed that 15% reported having been violence victims and 27% claimed to have engaged in violent behavior, more frequently emotional violence.5 Also in a sample of young people from college education, 52% admitted to be violent with their partners and 42% to have been violence victims.10

A study with a sample of 4,667 professional, high school, and college students aged 13 to 19 years revealed that 19.5% experienced emotional violence, 13.4% physical violence, and 6.7% more serious aggressions (punching, kicking, forcing the other to perform unwanted sexual acts, threatening with weapons, causing injuries that required medical assistance, among others).15 Among young violence perpetrators, 22.4% admitted having resorted to emotional violence, 18.1% to physical violence, and 7.3% to more serious aggressions.15

Another study with college students reported rates of emotional violence of 53.8%, sexual violence of 18.9%, physical violence without sequelae of 16.7%, and physical violence with sequelae of 3.8%.3

The present study aimed to determine DV prevalence in a sample of adolescents from a high school in the northern region of Portugal, as well as their knowledge and attitudes toward DV. The study also sought to evaluate the effectiveness of a brief intervention to empower adolescents with the ability to cope with DV.

Methods

Sample

This longitudinal and interventional study included six classes of high school students from the northern region of Portugal. Three classes from regular education and three classes from professional education were randomly selected, with each group including a 10th, 11th, and 12th grade class.

The three professional education classes were selected to be object of a brief intervention (intervention group) considering initial CADRI (Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory) and ADV (Attitudes Toward Dating Violence) survey assessment results. The remaining students only completed surveys from the presents study.

Surveys

CADRI survey, previously validated for the Portuguese adolescent population, was used to assess violent behavior in adolescent relationships.16 This survey includes two components: the first component, with 35 items, evaluates the use of abusive or non-abusive conflict resolution strategies; the second component, also with 35 items, evaluates the use of abusive or non-abusive conflict resolution strategies by the intimate partner.

To evaluate the intervention impact, ADV survey, also validated for Portuguese adolescents, was applied.8 This survey includes 76 items grouped into six subscales: Attitudes towards male emotional violence; Attitudes towards male physical violence; Attitudes towards male sexual violence; Attitudes towards female emotional violence; Attitudes towards female physical violence; and Attitudes towards female sexual violence.

Study design

Adolescents initially completed CADRI and ADV surveys, as well as a demographic survey. Due to logistical difficulties in analysing all adolescents included in the study, only professional students were selected for the intervention. This group was selected as an intervention target after revealing higher alcohol or drug consumption, peer violence, significantly more frequent use of abusive conflict resolution strategies, and significantly higher violence legitimization in demographic, CADRI, and ADV surveys. At the end of the third intervention session, adolescents again completed ADV survey to assess intervention’s potential impact on their attitudes toward DV. Adolescents were informed about the study’s voluntary nature and confidentiality and their legal guardians signed an informed consent statement to participate.

Description of intervention sessions

Adolescents included in the intervention participated in three DV sessions (one per week) with the duration of one hour and 30 minutes each.

The first session started with a dynamic presentation (adolescents were paired and tagged their name and something they identified with). Cards with DV truths and misconceptions were distributed and analysed, followed by group discussion.

The second session began with a brief review of the first session. The lecturer threw a ball to some students and the student holding the ball should complete the sentence: “Boys are ...” or “Girls are...”, as a means of discussing gender inequality in DV. Discussion was followed by a short theoretical DV presentation. “White Knight” story was distributed and analysed, allowing students to reflect on how power and control relationships are allowed in dating and how they escalate. Some relationship characteristics were presented − as respect, trust, jealousy, power, control, among others −, which adolescents classified as healthy/unhealthy. Finally, they watched a campaign video against DV.

In the last session, questions and remarks anonymously written by students were clarified. Strategies for safely ending a violent relationship and how to act in DV situations affecting peers were addressed. Lastly, adolescents presented DV posters previously prepared, conveying the message to their peers.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS® version 21. Correlation analysis was performed through Chi-square and Fisher’s tests. Intervention efficacy evaluation was performed through t-test for paired samples.

Results

This study included 138 high school students with a mean age of 16.7 ± 1.0 years, 51.4% (n=71) of which females. Of those, 46.7% were in the 12th grade, 27.7% in the 11th grade, and 25.5% in the 10th grade.

Regarding use of abusive and non-abusive conflict resolution strategies (Table I), 96.2% (n=102) of adolescents in the total sample reported using non-abusive strategies in conflict resolution. However, 75.5% (n=80) reported using abusive conflict resolution strategies, such as inciting jealousy, speaking in an aggressive manner, or recalling something negative from the past. Regarding severe violence, 33% of adolescents reported having physical and/or sexual violence behavior in their relationship, such as kissing without consent or hitting, pushing, kicking, or punching. Severe violence was more prevalent among boys (43.1% vs. 23.6% in girls). A total of 40.6% of adolescents reported having been victims of physical and/or sexual violence, with males reporting higher victimization (47.1% vs. 34.5% in females). Regarding threat behaviors, 59.4% of adolescents reported having already threatened their partners (52.7% females vs. 66.7% males) and 59.4% having already been threatened by their partners (49.1% females vs. 70.6% males).

Males reported to be significantly more often subject to threatening behaviors (p=0.017), while no statistically significant difference was found between genders for the remaining violence types.

Attending the 12th grade, having depression/anxiety symptoms, being sexually active, and being/having been exposed to domestic violence were factors significantly associated with the adoption of abusive conflict resolution strategies (p <0.05). Being male, attending the 12th grade, considering DV acceptable, assaulting colleagues, having friends with a DV history, being sexually active, and being/having been exposed to domestic violence were factors significantly associated with the adoption of severe violence (p <0.05).

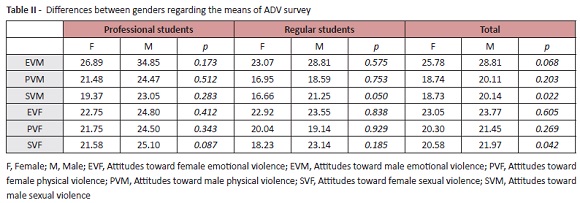

Regarding attitudes toward DV (Table II), boys had a higher legitimization rate for emotional, physical, and sexual violence perpetrated by both boys (emotional violence by male [EVM]; physical violence by male [PVM]; sexual violence by male [SVM]) and girls (emotional violence by female [EVF]; physical violence by female [PVF]; sexual violence by female [SVF]), with statistical significance for SVM (p=0.022) and SVF (p=0.042).

SVM legitimization was significantly associated with lower parental education and adolescents who reported having assaulted peers (p <0.05). A significant association was also found between maternal unemployment and higher PVF and SVF legitimization (p <0.05). SVF legitimization was significantly higher among boys (p <0.05). Adolescents who reported having friends with a DV history had a significantly higher EVM and PVM legitimization rate (p <0.05).

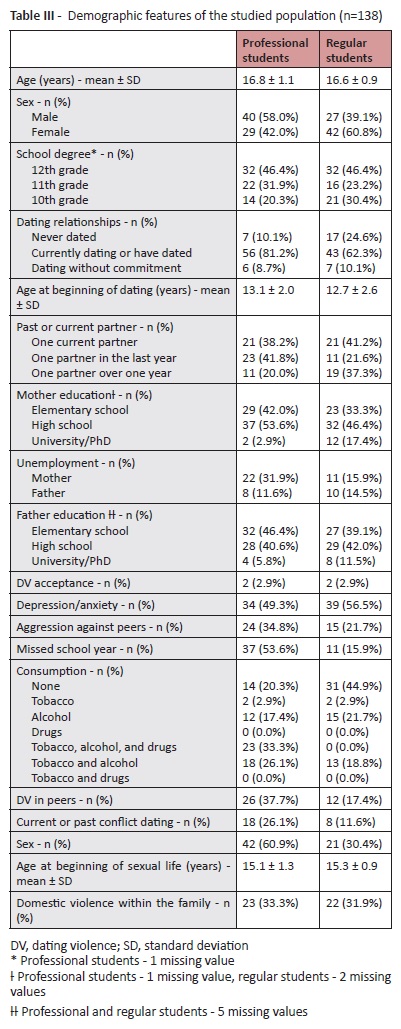

Differences in demographic data between professional and regular education groups are described in Table III.

Students in professional education had significantly lower maternal education (p=0.017) and unemployment (p=0.031), past school failure (p=<0.001), drug or alcohol consumption (p=0.003), peer DV history (p=0.007), conflictive relationships (p=0.048), sex (p=<0.001), and abusive conflict resolution strategies (p=0.033). They were also more frequently from male gender (p=0.027).

No significant differences were identified between both groups regarding age, grade level, father’s education and unemployment, DV acceptance, depression, aggression toward peers, age of first date and sex, domestic violence witnessing, use of non-abusive strategies, severe violence, or threatening behaviors.

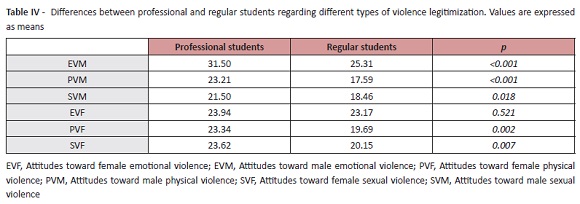

Regular education students reported higher PVF legitimization, but without statistical significance. Legitimization of remaining types of violence was higher in boys, with statistical significance regarding SVM (p=0.05) (Table II). When comparing both groups (Table IV), professional students revealed higher violence legitimization, which was statistically significant (p <0.05) for all types of violence except EVF.

Sixty-nine adolescents attended the first intervention session, eight of which did not participate in the following sessions and were therefore excluded from the study. Three adolescents were additionally excluded for incorrect survey filling. Overall, 58 adolescents were included in the study to assess intervention effectiveness, including a change in attitudes toward DV (Table V). In all areas, violence legitimization was higher after the intervention, with statistical significance for SVM (p=0.003). Regarding gender differences, boys showed decreased EVM legitimization but without statistical significance. However, violence legitimization was higher in all other types of violence, with statistical significance for SVM (p=0.001). As for girls, there was a non-statistically significant decrease in SVF legitimization and a non-significant legitimization increase for the remaining types of violence.

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

Discussion

This study showed that a high percentage of adolescents use abusive conflict resolution strategies (75%) and severe violence behaviors (33%). Additionally, 40.6% of adolescents are or have been severe violence victims, stressing the urgent need to develop intervention strategies and programs accessible to all adolescents at an earlier age, as dating relationships begin early in life. Although results from this study are worrisome compared with other studies conducted in the Portuguese adolescent population, in those studies a distinction was made between major and minor violence, while in this study any act of physical and/or sexual violence was considered an act of severe violence.3,15

Interestingly, in this study male adolescents reported more severe violence behaviors than females, in disagreement with previous studies. This may be explained by the fact that social pressure more easily condemns these behaviors in boys, and thus they are more reluctant to admit them.3,5,15 Boys also admitted more often being violence targets, a trend found in several studies which contradicts the idea that they are always the aggressors and girls always the victims and reinforces the notion that relationship violence is often mutual.3,5,12,13

Males revealed a higher tolerance toward different types of violence, whether perpetrated by boys or girls, a trend also found in various studies and explained by the greater likelihood of boys being more social agressive in their interpersonal relationships.4,15,17

According to a study conducted in Portugal, adolescents in professional education have a higher violence prevalence in their relationships.15 Indeed, students in professional education in this study revealed increased risk factors for DV, including higher alcohol or drug consumption, peer violence, significantly more frequent use of abusive conflict resolution strategies, and significantly higher violence legitimization. Thus, this group of adolescents represents an urgent intervention target.

Despite adolescents’ active participation during intervention sessions and these having been described as positive and enlightening, there was an increase in legitimization of male and female sexual and physical violence and female psychological violence after the intervention, with statistical significance for male sexual violence. There was also a non-significant decrease in legitimization of male psychological violence. In females, a non-significant decrease in female sexual violence legitimization and a non-significant increase in male and female psychological and physical violence as well as male sexual violence were reported.

These results may be partially justified by intervention limitations, including its short duration and predominantly informative (although also dynamic) nature. Professional education students showed higher violence tolerance what, in addition to above-described factors, may have contributed to a greater difficulty by this group in changing attitudes towards violence. Intervention facilities may have also had a negative impact on survey filling, by not providing suitable privacy to adolescents.

Non-random selection of students submitted to the intervention also represents a study limitation, as well as memory bias from the fact that the same students replied to ADV survey with one month interval. A desired follow-up assessment could not be performed, since school year ended and adolescents left school for internships.

In conclusion, physical and sexual violence were reported by one third of adolescents in this study and 75.5% reported using abusive conflict resolution strategies. Male gender, depression/anxiety symptoms, attending the 12th grade, being sexually active, violence within the family, violence acceptance, and violence among peers were risk factors for DV. Despite adolescents’ satisfactory participation in the intervention, ADV survey results at the end of intervention revealed its apparent non-effectiveness. However, in addition to study limitations, we believe that ADV survey addresses issues that are still not taken seriously by adolescents, probably contributing to the unexpected results. Noteworthy, one adolescent approached teachers during the intervention period reporting having been victim of DV and seeking help, emphasizing the relevance of such initiatives.

Screening and intervention strategies aimed at detecting and preventing DV, particularly directed at boys, are an unmet need. Furthermore, the increasingly early age at which adolescents begin dating relationships reveals the need for interventions at earlier ages.

REFERENCES

1. Caridade S. Vivências Íntimas Violentas : Uma Abordagem Científica. 1st. Braga: Almedina; 2011, p. 292. [ Links ]

2. Caridade S, Machado C. Violência nas relações juvenis de intimidade: uma revisão da teoria, da investigaçao e da prática. Psicologia. 2013; 27:91-113. [ Links ]

3. Paiva C, Figueiredo B. Abuso no relacionamento íntimo - Estudo de prevalência em jovens adultos portugueses. Psychologica. 2004; 36:75-107. [ Links ]

4. Matos M, Machado C, Caridade S, Silva MJ. Prevenção Da Violência Nas Relações de Namoro: Intervenção Com Jovens Em Contexto Escolar. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática - 2006, 8:55-75. [ Links ]

5. Machado C, Matos M, Moreira AI. Violência nas relações amorosas: Comportamentos e atitudes na população universitária. Psychologica. 2003; 33:69-83. [ Links ]

6. Hickman LJ, Jaycox LH, Aronoff J. Dating Violence among Adolescents: Prevalence, Gender Distribution, and Prevention Program Effectiveness. Trauma, Violence, Abus. 2004; 5:123-42. [ Links ]

7. Connolly J, Josephson W. Aggression in Adolescent Dating Relationships: Predictors and Prevention. Prev Res. 2007; 14:3-5. [ Links ]

8. Saavedra R, Machado C. Violence in dating relationships among adolescents: Evaluation of the impact of a program of awareness and information in schools. Anal Psicol. 2012; 30:109-30. [ Links ]

9. Paiva C, Figueiredo B. Abuso no contexto do relacionamento íntimo com o companheiro: Definição, prevalência, causas e efeitos. Psicol Sáude Doenças. 2003; 4:165-84. [ Links ]

10. Oliveira MS, Sani AI. Comportamentos dos jovens universitários face à violência nas relações amorosas. Actas do VIII Congr Galaic Psicopedag. 2005:1061-74. [ Links ]

11. Caridade S, Machado C. Violência na intimidade juvenil: Da vitimação à perpetração. Análise Psicológica. 2006; 24:485-93. [ Links ]

12. Machado C, Martins C, Caridade S. Violence in Intimate Relationships: A Comparison between Married and Dating Couples. J Criminol. 2014: 897093. [ Links ]

13. O’Keefe M. Factors mediating the link between witnessing interparental violence and dating violence. J Fam Violence. 1998; 13:39-57. [ Links ]

14. Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Newman DL, Fagan J, Silva PA. Gender differences in partner violence in a birth cohort of 21-year-olds: Bridging the gap between clinical and epidemiological approaches. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997; 65:68-78. [ Links ]

15. Machado C, Caridade S, Martins C. Violence in juvenile dating relationships self-reported prevalence and attitudes in a portuguese sample. J Fam Violence. 2009; 25:43-52. [ Links ]

16. Simões MR, Almeida L, Gonçalves M, Machado C. Instrumentos e Contextos de Avaliação Psicológica (Vol. I). 1st. Coimbra: Almedina; 2011, p. 312. [ Links ]

17. O’Keefe M, Treister L. Victims of dating violence among high school students: Are the predictors different for males and females? Violence Against Woman. 1998; 4:195-223. [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

Sofia Simões Ferreira

Department of Pediatrics

Centro Hospitalar Vila Nova de Gaia e Espinho

Rua Dr. Francisco Sá Carneiro

4400-129 Vila Nova de Gaia

Email: sofiaferreira20@gmail.com

Received for publication: 07.08.2019. Accepted in revised form: 07.02.2020