Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Nascer e Crescer

versão impressa ISSN 0872-0754versão On-line ISSN 2183-9417

Nascer e Crescer vol.29 no.2 Porto jun. 2020

https://doi.org/10.25753/BirthGrowthMJ.v29.i2.18631

REVIEW ARTICLES | ARTIGOS DE REVISÃO

Growing in the shadows of suicide

Crescer nas sombras do suicídio

Ana Vera CostaI, Sandra MendesI, Ana Sofia PiresI, Sara MeloI, Sandra BorgesI, Joana JorgeI, Graça MendesI

I. Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Centro Hospitalar Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho. 4434-502, Vila Nova de Gaia, Portugal.ana.bessa.costa@chvng.min-saude.pt; sandra.mendes@chvng.min-saude.pt; ana.rodrigues.pires@chvng.min-saude.pt; sara.veloso.melo@chvng.min-saude.pt; sborges@chvng.min-saude.pt; joana.jorge@chvng.min-saude.pt; gmendes@chvng.min-saude.pt

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Children/adolescents mourning the death of a primary caregiver face several challenges, including bond breaking and family restructuring due to loss. The negative connotation associated with suicide loss is enhanced by stigma, increasing acceptance difficulties and feelings of isolation, abandonment, shame, and guilt in face of what happened.

Objective: The aim of this study was to retrieve data on childhood bereavement due to primary caregiver suicide and explore psychopathological and psycho-affective developmental consequences of this type of grief.

Methods: Literature review of articles published on PubMed database about the subject.

Results and Discussion: Bereavement of a suicidal parent is associated with multiple psychopathological conditions: mood disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, self-injurious behavior, suicidal behavior. Suicide and depressive disorder risk is higher when parental death occurred early in life course, with maternal suicide having greater impact. Antidepressants are more commonly used in cases of early parental death from suicide and are associated with increased hospitalizations for Major Depression and Bipolar Affective Disorder in adulthood. Consequences of parental death by suicide may be explained by several factors, as genetics, biological reactions, psychological factors originated from loss of an attachment figure, or social and environmental changes.

Conclusions: Parental suicide can be impactful for children’s developmental trajectory and later functioning level. The authors alert to the need for prevention and early intervention strategies associated with this process.

Keywords: bereavement; parental death; suicide; transgenerational

RESUMO

Introdução: São vários os desafios das crianças/adolescentes enlutados de um cuidador principal, entre os quais a quebra de um vínculo e reestruturação familiar em função da perda. No caso da perda por suicídio, há um acréscimo de uma conotação negativa, estigmatizante, aumentando dificuldades de aceitação, sendo referidos sentimentos de isolamento, abandono, vergonha e culpa face ao sucedido.

Objetivo: O objetivo deste estudo foi analisar os dados de luto na infância por suicídio de um cuidador principal e explorar as consequências deste tipo de luto no processo de desenvolvimento, bem como as suas consequências psicopatológicas.

Métodos: Revisão da literatura publicada na base de dados PubMed sobre o tema.

Resultados e Discussão: O luto de uma figura parental por suicídio encontra-se associado a múltiplos quadros psicopatológicos: perturbações do humor, perturbação do stress pós-traumático, abuso de substâncias, comportamentos auto-lesivos, comportamentos suicidários. O risco de suicídio e perturbações depressivas é tanto maior quanto mais precoce for a morte da figura parental, revelando maior impacto o suicídio materno. Verifica-se uma maior utilização de antidepressivos face a uma morte parental precoce por suicídio e a mesma está associada a um aumento de hospitalização por Depressão Major e Perturbação Afetiva Bipolar na idade adulta. As consequências da morte parental por suicídio poderão ter várias origens explicativas genética, reações biológicas ao stress, causa psicológica da perda de uma figura de vinculação ou ainda por mudanças sociais ou ambientais.

Conclusões: O suicídio parental pode ser impactante nas trajetórias desenvolvimentais e no nível posterior de funcionamento. Neste processo, os autores alertam para a necessidade de prevenção e estratégias de intervenção.

Palavras-chave: luto; morte parental; suicídio; transgeracional

Introduction

Children/adolescents mourning the death of a primary caregiver face several challenges, including bond breaking and family restructuring due to loss.1 According to Freud, mourning is a natural experience in response to loss of an object of love, supposing a change in object relation.2 Grief experience will depend on relationship patterns established with the deceased, child’s age, temperament, Piaget cognitive development stage, cultural influences, and presence of other significant figures in the child’s life, which represents an important protective factor. Children with markedly egocentric thinking blame death on themselves and may feel insufficiently loved when facing abandonment by loss, showing death and abandonment fear. Under the age of five, in the preoperational stage, death is felt as reversible and part of magical thinking. Between 6−9 years old, children take death as irreversible, understanding it as a concrete state of vital body function interruption. Children show awareness of the impossibility of controlling over the death event and understand causality as opposed to randomness, still resisting in accepting the universality of death. At 9−15 years, children understand the mature concept of universal and inevitable death, demonstrating fear regarding their loved ones. Pre-adolescents, with formal thinking, develop physiological and theological explanations for the occurrence and may later start questioning their own death. Grief experience changes throughout each new developmental stage, with a new redesign of the grief process, making children revisit suffering at different stages.3

Reactions of sadness, anger, confusion, and isolation are similar, regardless of the type of death. Connotation associated with suicide loss is even more negative and enhanced by stigma, increasing acceptance difficulties (additional burden of being intentional and not making sense). Feelings of isolation, abandonment, shame, guilt, and responsibility have also been referred.4 In addition to loss of a primary caregiver, children are exposed to suicide death of a significant person. Children are particularly vulnerable to suicide due to its unpredictability, stigmatizing reactions from the surrounding environment and communication difficulties with adults regarding the incident.5

It is easier to keep silent, devalue the suicidal individual, and devalue family difficulties when talking about psychological factors leading to suicide. An unprotected mourning may be created this way, with the mourner deprived of the right to suffer.4

Death by suicide may not be shared − out of shame, guilt, fear of rejection, and judgment or anxiety related to stigma −, leading to lack of support and understanding, promoting isolation, decreasing confidence, and leading to fear of abandonment.4 The transgenerational power of suicide includes feelings of guilt, shame, family secrets, evasion, avoidance of parenting, and communication of negative expectations, which can spread to many generations.6

Published studies have been inconsistent in differentiating consequences of mourning for suicide and for other causes.5,7-9 Despite the lack of studies and consistent results, this is a very important issue in clinical practice, as the offspring of suicidal parents are at risk for a variety of psychopathological problems, including suicidal behavior, mood disorders, personality disorders, and substance abuse, among others.5,10

Objectives

The aim of the present study was to conduct an exploratory bibliographic analysis about children and adolescent grief due to primary caregiver suicide and to analyze psychopathological as well as psycho-affective developmental consequences of this type of grief. Exploring this subject is relevant to develop supportive care measures directed at suicide-bereaved children.

Methods

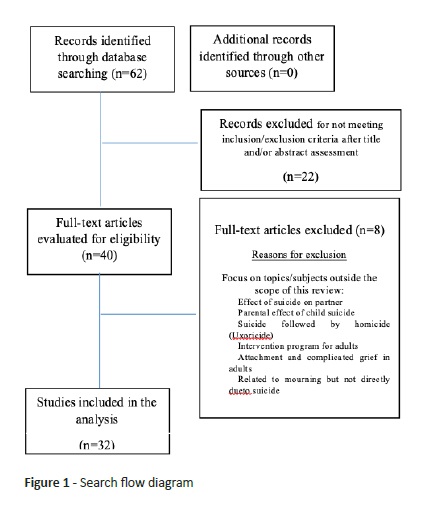

A literature review was conducted on PubMed database in March 2018 using the following MeSH terms: “bereavement” AND “suicide” AND “parental death” AND (“adolescent” OR “child” OR “infant” OR “ child, preschool”). Articles were selected according to the following criteria: a) population: children or adolescents at the time of exposure; b) exposure: death of a primary caregiver by suicide; c) outcome: grieving process difficulties and psychopathology throughout development and into adulthood. Studies were excluded if not meeting inclusion criteria, diverging from study purpose, not written in English or Portuguese, or article’s full text could not be retrieved online. When the decision for study inclusion or exclusion could not be made based on title and abstract reading only, article’s full text was read to ensure a better decision.

Results and discussion

Search strategy retrieved 62 articles, 32 of which were selected according to inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Impact and psychopathology

Long-term consequences are most impactful on mourners from unnatural causes (suicide, overdose, homicide) when compared to other predictable types of grief.11 Stigma and acceptance difficulties in adult caregivers are often associated with lack of honesty about death causes.12 Suicide mourning was associated with increased feelings of shame, anxiety, anger, and greater externalizing behaviors compared with other grief causes.13, 14

Mourning a parental figure due to suicide has a lasting effect throughout development and adulthood, being associated with poorer functionality and multiple psychopathological conditions: complicated childhood mourning disorder, non-suicidal self-injurious behavior, suicidal behavior and effective suicide, major depressive disorder, bipolar affective disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, multiple risk behaviors and substance abuse.7,9-12,14-25,27-29

Parental suicide can be impacting on children’s developmental trajectory and later functioning level. Bren et al. assessed acquisition of developmental skills in a group of children and adolescents whose parental figure suddenly died (including by suicide) compared with ungrieved children and found that the first had lower working skills, career and educational aspirations, and peer attachment.15 These results were not related to age at time of death, gender of the deceased parent, or death cause.

In a prospective cohort study assessing sudden death mourners, 10.4% of children and adolescents whose primary caregiver committed suicide developed complicated grief disorder, while 30% displayed increased grief reactions, with increased risk of depression and decreased functionality.16 Prior psychopathology of the suicidal caregiver or child was associated with a higher risk of developing the disorder. The most complicated mourning process was related to non-acceptance and associated with increased feelings of self-guilt and holding others accountable for what occurred.12,16-18

The transgenerational transmission of suicidal behavior is higher. Compared with children whose parents are alive or whose parents died from other causes than suicide, children whose parents have committed suicide have a higher risk of dying by suicide or committing suicide attempts. Similarly, children of parents with a history of suicide attempts have a higher risk of committing or attempting suicide.7 A population-based study showed a higher incidence of suicide death in bereaved suicide from other causes or non-bereaved, and this incidence was higher when parental death occurred before the age of six years, remaining high in the first group for at least 25 years.20 Risk of suicide was 82% higher in children of parents who committed suicide compared to parents who died from other causes.20 Risk of suicide was significantly higher in older siblings.20 Fatal or non-fatal suicide parenting behaviors are associated with suicidal behavior in the offspring, with children being more vulnerable than adolescents and adults.7,10,22 Risk of suicide in the offspring was three times higher when parental suicide death occurred before adulthood.10

While suicide risk was higher for males, the same was not true for non-suicidal self-injurious behaviors.7,20,11 Maternal behavior has a greater influence on learned behavior, as well as an increased impact on offspring suicide compared with paternal suicide.7,20,19 However, risk of non-suicidal self-injurious behavior is similar in maternal and paternal suicide.11 In case of non-suicidal self-injurious behavior, a strong association is observed in children who have lost a primary caregiver due to suicide, which weakens if the loss occurred during adolescence.11

Depression incidence is higher in suicide-bereaved children.7,17,29 Children of parents who committed suicide have a slightly higher risk of developing subsequent depression compared with children of parents who died from other causes.7 Compared to other grief causes, parental suicide death can lead to the most severe depressive symptoms.23 Risk of Major Depressive Disorder is higher after maternal suicide compared to paternal suicide.19,23,24,29 The closer the relationship with the deceased caregiver, the greater the risk of depression, and when complicated grief disturbances occur, depression risk increases even more.7,17,29 Caregiver’s grief in childhood is associated with increased risk of hospitalizations for Major Depression in adulthood, with a stronger association with suicide compared with other grief causes.24,10,19 A population-based Danish national study reported an increase in antidepressant use due to early parental death, with a higher association in case of suicide mourning, especially in women and in cases of early maternal figure loss.25 Risk of starting antidepressants ensues up to two years after the loss, with an increased risk of long-term treatment, suggesting potential chronicity.25

There is also an increase in hospitalization for future Bipolar Affective Disorder in the development trajectory after an early death of a caregiver by suicide, but not in mourning for other causes, even after adjusting for parental psychopathology history.24 Another study demonstrated an increased risk of bipolar affective disorder in children of parents who committed suicide compared with children with living parents and children bereaved by parental death for another cause.26 In case of maternal death by suicide before the age of ten, risk of bipolar affective disorder in adulthood is seven times higher.26

Compared with sudden death causes (e.g. heart attack, car accident, etc.), prolonged death and suicide processes have higher levels of post-traumatic stress disorder.12,17

After parental death, children and adolescents have higher rates of violent and sexual risk behaviors, increased in cases of Anxiety or Antisocial Personality Disorder diagnoses of the deceased caregiver.28 Increased abuse of alcohol and other recreational substances reaches a higher level in bereaved youth.27,29 Clinicians dealing with grieving adolescents should be more aware of potential substance abuse.27 Children of parents who committed suicide contribute to a higher incidence of hospitalizations for drug abuse.10

Some studies suggest early death for cardiovascular causes in children of parents who commit suicide. If, on the one hand, obesity seems predominant in bereaved children (with no differences between the type of death), on the other hand caregiver depression before the suicide event is associated with children’s normal body mass index. However, caregiver depression in non-bereaved children has a strong association with obesity.30

It should also be noted that the surviving caregiver, immersed in his/her own pathology or grief, may become disconnected from the child’s emotional needs and may exacerbate their psychopathological disorders. Surviving caregivers showed higher rates of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder and less functionality compared to ungoverned controls.17 Surviving caregivers showed higher depression symptoms in sudden death cases.12 As survivor caregiver mourning predicts depression in childhood, higher surviving caregiver functioning can be a protective factor for child depression.16,17

Etiological explanatory hypotheses

Consequences of parental death by suicide may have several explanations: genetics, biological stress reaction, psychological cause from loss of a bonding figure, emotional dysregulation, or even social and environmental changes resulting from the loss.11,20,26

Rates of psychiatric illness are higher in bereavement suicide victims compared with bereavement victims from other sudden deaths, suggesting a pre-existing family vulnerability (multi-headed families with psychosocial risk, exposure to previous parental psychiatric illness) and increased risk of adverse outcomes in the grieving process.16,26 Genetic predisposition may explain a greater association between Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder in children of parents who committed suicide, depending on the underlying psychopathological history.11,20,26

Parenting influence and mental state of the surviving caregiver may also explain suicide adverse consequences in the offspring.12,16-18

Regarding age at the time of loss, studies have indicated that younger populations are at increased risk, which translates into greater difficulty in elaborating and re-elaborating the loss, increased suicidal behavior as children are younger at the time of parental suicide, and decreased risk of developing Depressive Disorder with increasing age at the time of loss.10,20,24 Young children are more dependent on their parents and lack cognitive and emotional strategies to internalize death and manage feelings of loss. Moreover, high stress levels are present and, in a neurobiological approach, chronic stress at an early age may affect brain development and predispose to depression.11,20

Transgenerational transmission of suicidal behavior can be explained by the learning effect of behavior or the genetic predisposition to mental disorder that leads to behavior.7

Parental role impairment can lead to an attempt to assume the deceased caregiver family role by older fraternity children, exposing themselves to an increased risk.20

Intervention

Parental suicide can be impacting on the developmental trajectory and later functioning level throughout life course. During this process, awareness should be raised of the need for prevention and early intervention strategies, enhancing the importance of recognizing particular features in children and their families and mobilizing protective and resilience factors. Appropriated family and child psychoeducation applied to suicide nature and development and experience, awareness of feelings of loss, and normalization of bereavement process becomes an effective strategy in helping children and adolescents manage their feelings and cope with the grieving process.4,31,32

Several communication difficulties may arise between the surviving caregiver and the bereaved child / young person. This issue should be approached with authenticity/veracity and the child cannot be denied the reality of loss, a loss that must be explained using concrete words and avoiding euphemisms. Death and death cause must be explained according to the child’s level of developmental understanding in every particular situation. In case of suicide death, it is important to reassure children that they are not responsible for what happened, that none of the caregivers is responsible, that the deceased was ill, and that death is an irreversible part of the natural life cycle. The child should have the opportunity to ask questions that must be heard and honestly answered. Feelings related to death, loss, fear, and lack of knowledge about the after death can be shared. Consistency regarding death causes and circumstances is very important. Taking care of grieving children necessarily implies taking care of the other bereaved caregiver, who may be absolutely shaken up and unable to deal with the child’s emotions, believing that he/she should spare them from suffering. Such situation increases isolation and abandonment feelings. Conversely, it is important to share feelings of sadness with the child, who should also be encouraged to express feelings of sadness and anger and have support throughout his/her emotional experience. It should be noted that loss impact on young children is often associated with routine changes. However, children need predictability and consistency, and presence of available and supportive figures is extremely important. The child should also be explained that a farewell is usual after death, to share feelings of loss but also good memories of the time spent together. The child’s decision in participating in funeral ceremonies and other family rituals should be valued.1-4,31,32

Group intervention for bereaved suicide children may be a good strategy, since it diminishes the isolation effect that a suicide bereavement can cause, showing effectiveness in reducing anxiety, depression, and scholar dropout rate.32 A profound understanding of mourning phenomena in children of suicidal descent may help improve psychoeducational strategies, promote protective factors, and reduce stigma.4 Hope instillation, emphasizing on universality and interpersonal learning, is particularly useful therapeutic factor and facilitates cohesion and catharsis in a safe place, bringing together psycho-educational measures. Hope promotes persistence of normal psycho-affective development and resilience among survivors. Among bereaved peers, the child develops satisfying relationships, increasing self-esteem and lowering abandonment and disapproval perception. They also expand communication, decreasing inappropriate behavioral expression.31 Interventions should not forget the bereaved caregiver for treatment of his/her own psychopathology and integration in positive parenting programs.16,32,33 Familiar intervention in grief may also be useful in decreasing levels of depression and antisocial behavior as in decreasing suicidal thoughts, and acting out.34 Concerning psychosocial interventions in parental suicide-bereaved children and adolescents, a systematic literature review from 1975 to 2016 retrieved only two studies, evidencing lack of studies on the subject and failing to meet review objectives of bringing empirical validity to child’s interventions.35 A cognitive behavioral-based intervention program for bereaved children and adolescents has been shown to improve long-term bereavement, post-traumatic stress, and depression and is less effective in those facing suicide

Limitations

No international or national data was found regarding the proportion of children/adolescents losing a caregiver due to suicide. Most studies refer to cases (and with patients were at some point hospitalized or followed on an outpatient setting), which may represent a bias. Data is lacking regarding the total number of cases of children whose parents committed suicide. Population-based studies are required to assess the pediatric proportion of bereaved suicide, as well as psychopathology in the offspring of parents who committed suicide using standardized tools.

Despite establishing an age comparison at time of grief, no study reported data concerning development of the death concept (especially suicide) and the understanding process throughout each developmental stage.

Conclusion

Children and adolescents’ experience with the grieving process depends on their developmental stage. Suicide grief becomes more difficult to elaborate due to its unpredictability and to attributing caregiver abandonment as volunteer. It should also be noted that the surviving caregiver, immersed in his/her own suffering, may become disconnected from the child’s emotional needs.

Children and bereaved youth from parental suicide are considered a risk group and may have impaired developmental trajectories, later level of functioning throughout life, course and higher psychopathological risk. Bereavement of a suicidal parent is associated with multiple psychopathological conditions: Mood Disorders, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, Substance Abuse, Self-injurious Behavior, and Suicidal transgenerational Behavior.

Consequences of parental death by suicide may have several explanations: genetics, physiological stress reaction, psychological cause due to bonding figure loss, or social and environmental changes.

With this study, the authors alert to the need for psychopathological prevention and early intervention strategies, which are currently poorly validated. Equally important is to conduct populational studies to identify the prevalence of suicide descendants and incidence rates of psychopathological conditions.

REFERENCES

1. Bowlby J. Loss, sadness and depression. Attachment and Loss, Volume III. Travistock Institute of Human Relations, 1980. [ Links ]

2. Freud S. Trauer und melancholie.. Translation, introduction and notes: Marilene Carone. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 1ª electronic edition, 2013. [ Links ]

3. Golse B. Le developpment affetif et intellectuel de l’enfant. Translation: Emmanuel Pestana. Climepsi editores, 2005. [ Links ]

4. Schreiber JK, Sands DC, Jordan JR. The Perceived Experience of Children Bereaved by Parental Suicide. Omega (Westport). 2017; 75:184-206. [ Links ]

5. Hung NC, Rabin LA. Comprehending childhood bereavement by parental suicide: a critical review of research on outcomes, grief processes, and interventions. Death Stud. 2009; 33:781-814. [ Links ]

6. Cain AC. Parent suicide: pathways of effects into the third generation. Psychiatry. 2006; 69:204-27. [ Links ]

7. Geulayov G, Gunnell D, Holmen TL, Metcalfe C. The association of parental fatal and non-fatal suicidal behaviour with offspring suicidal behaviour and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2012; 42:1567-80. [ Links ]

8. Brown AC, Sandler IN, Tein JY, Liu X, Haine RA. Implications of parental suicide and violent death for promotion of resilience of parentally-bereaved children. Death Stud. 2007; 31:301-35. [ Links ]

9. Janet Kuramoto S, Brent DA, Wilcox HC. The impact of parental suicide on child and adolescent offspring. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2009; 39:137-51. [ Links ]

10. Wilcox HC, Kuramoto SJ, Lichtenstein P, Långström N, Brent DA, Runeson B. Psychiatric morbidity, violent crime, and suicide among children and adolescents exposed to parental death. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010; 49:514-23 [ Links ]

11. Rostila M, Berg L, Arat A, Vinnerljung B, Hjern A. Parental death in childhood and self-inflicted injuries in young adults-a national cohort study from Sweden. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016; 25:1103-11. [ Links ]

12. Kaplow JB, Howell KH, Layne CM. Do circumstances of the death matter? Identifying socioenvironmental risks for grief-related psychopathology in bereaved youth. J Trauma Stress. 2014; 27:42-9. [ Links ]

13. Cerel J, Fristad MA, Weller EB, Weller RA. Suicide-bereaved children and adolescents: a controlled longitudinal examination. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999; 38:672-9. [ Links ]

14. Cerel J, Fristad MA, Weller EB, Weller RA. Suicide-bereaved children and adolescents: II. Parental and family functioning. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000; 39:437-44. [ Links ]

15. Brent DA, Melhem NM, Masten AS, Porta G, Payne MW. Longitudinal effects of parental bereavement on adolescent developmental competence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2012; 41:778-91. [ Links ]

16. Melhem NM, Porta G, Shamseddeen W, Walker Payne M, Brent DA. Grief in children and adolescents bereaved by sudden parental death. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011; 68:911-9. [ Links ]

17. Melhem NM, Walker M, Moritz G, Brent DA. Antecedents and sequelae of sudden parental death in offspring and surviving caregivers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008; 162:403-10. [ Links ]

18. Melhem NM, Moritz G, Walker M, Shear MK, Brent D. Phenomenology and correlates of complicated grief in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007; 46:493-9. [ Links ]

19. Kuramoto SJ, Stuart EA, Runeson B, Lichtenstein P, Långström N, Wilcox HC. Maternal or paternal suicide and offspring’s psychiatric and suicide-attempt hospitalization risk. Pediatrics. 2010; 126:e1026-32. [ Links ]

20. Guldin MB, Li J, Pedersen HS, Obel C, Agerbo E, Gissler M, et al. Incidence of Suicide Among Persons Who Had a Parent Who Died During Their Childhood: A Population-Based Cohort Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015; 72:1227-34. [ Links ]

21. Burrell LV, Mehlum L, Qin P. Risk factors for suicide in offspring bereaved by sudden parental death from external causes. J Affect Disord. 2017; 222:71-78. [ Links ]

22. Burrell LV, Mehlum L, Qin P. Sudden parental death from external causes and risk of suicide in the bereaved offspring: A national study. J Psychiatr Res. 2018; 96:49-56. [ Links ]

23. Pitman A, Osborn D, King M, Erlangsen A. Effects of suicide bereavement on mental health and suicide risk. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014; 1:86-94. [ Links ]

24. Appel CW, Johansen C, Deltour I, Frederiksen K, Hjalgrim H, Dalton SO, et al. Early parental death and risk of hospitalization for affective disorder in adulthood. Epidemiology. 2013; 24:608-15. [ Links ]

25. Appel CW, Johansen C, Christensen J, Frederiksen K, Hjalgrim H, Dalton SO, et al. Risk of Use of Antidepressants Among Children and Young Adults Exposed to the Death of a Parent. Epidemiology. 2016; 27:578-85. [ Links ]

26. Tsuchiya KJ, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB. Parental death and bipolar disorder: a robust association was found in early maternal suicide. J Affect Disord. 2005; 86:151-9. [ Links ]

27. Hamdan S, Melhem NM, Porta G, Song MS, Brent DA. Alcohol and substance abuse in parentally bereaved youth. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013; 74:828-33. [ Links ]

28. Hamdan S, Mazariegos D, Melhem NM, Porta G, Payne MW, Brent DA. Effect of parental bereavement on health risk behaviors in youth: a 3-year follow-up. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012; 166:216-23. [ Links ]

29. Brent D, Melhem N, Donohoe MB, Walker M. The incidence and course of depression in bereaved youth 21 months after the loss of a parent to suicide, accident, or sudden natural death. Am J Psychiatry. 2009; 166:786-94. [ Links ]

30. Weinberg RJ, Dietz LJ, Stoyak S, Melhem NM, Porta G, Payne MW, et al. A prospective study of parentally bereaved youth, caregiver depression, and body mass index. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013; 74:834-40. [ Links ]

31. Mitchell AM, Wesner S, Garand L, Gale DD, Havill A, Brownson L. A support group intervention for children bereaved by parental suicide. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2007; 20:3-13. [ Links ]

32. Pfeffer CR, Jiang H, Kakuma T, Hwang J, Metsch M. Group intervention for children bereaved by the suicide of a relative. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002; 41:505-13. [ Links ]

33. Spuij M, Dekovic M, Boelen PA. An open trial of ‘grief-help’: a cognitive-behavioural treatment for prolonged grief in children and adolescents. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2015; 22:185-92. [ Links ]

34. Sandler I, Tein JY, Wolchik S, Ayers TS. The Effects of the Family Bereavement Program to Reduce Suicide Ideation and/or Attempts of Parentally Bereaved Children Six and Fifteen Years Later. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2016; 1:S32-8. [ Links ]

35. Journot-Reverbel K, Raynaud JP, Bui E, Revet A. Support groups for children and adolescents bereaved by suicide: Lots of interventions, little evidence. Psychiatry Res. 2017; 250:253-55. [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência | Dirección para correspondencia | Correspondence

Ana Vera Costa

Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Centro Hospitalar Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho

Rua Conceição Fernandes

4434-502, Vila Nova de Gaia

Email: ana.bessa.costa@chvng.min-saude.pt

Received for publication: 26.09.2019. Accepted in revised form: 13.03.2020