Introduction

Findings in the physical examination of the external genitalia in children are often a source of concern for parents and caregivers, not only due to the emotional significance people attribute to these structures − in part for their role in the reproductive function −, but also to the potential physical and psychological impact on the child.

Due to the role in the child’s close monitoring and periodic surveillance, the family physician has a crucial role in identifying and initially guiding these situations. Physical examination is a fundamental part of the child’s regular clinical evaluation and usually the most useful and effective tool for establishing a specific diagnosis. Variants of normal with maintenance of normal physiological function are the most frequent cases, not requiring intervention other than clinical surveillance and reassurance. However, some cases require medical intervention, frequently in the secondary health care setting, with early intervention being key for success of implemented measures.

As the family physician is often responsible for diagnosing these anomalies, he/she should be informed about guidelines for each particular situation, not only for reassuring parents in cases without pathological significance, but also for properly and timely referring the child to secondary health care, when necessary.

Objectives

To review available evidence and discuss the diagnosis, medical approach, and guidance at primary health care of the principal anomalies of the female external genitalia in pediatric age. Discussion of anomalies related to sexual differentiation disorders is beyond the scope of this article, since they are frequently diagnosed in hospital setting and have a highly specific approach.

Changes in physical examination of the female genital tract

Fusion/coalescence of labia minora

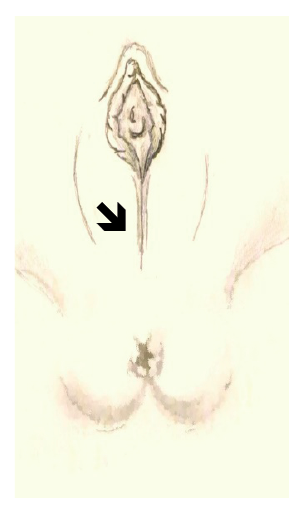

Fusion of labia minora, also designated labial adhesions or labial coalescence, refers to adhesion of the small vaginal labia on the midline, often in upward direction.1 Physical examination often reveals a thin semitransparent pale membrane between the labia minora, sometimes obstructing the vaginal introitus (Figure 1).2 The condition has an incidence of 1.8−3.3% at two years of age and a peak between 13 and 23 months.3 However, several minor cases are likely to go unnoticed in regular observations, with some authors pointing real incidence rates as high as 40%.4 Tissue hypoestrogenism, more pronounced between the age of three months and six years, seems to be the most determining factor for development of this alteration, even though studies have not yet found a clear link between hypoestrogenism and incidence of this pathology.3

Chronic vulvar inflammation, poor hygiene habits, infection, or genital trauma (including sexual abuse and female circumcision) may contribute to this alteration by acting on a hormonally propitious terrain.5

Diagnosis is clinical and usually asymptomatic. In some cases, the child may report local itching, pain, or genital discharge.6

Although rare, recurrent urinary and vulvovaginal infections are possible complications. Coalescence of labia minora may also interfere with genital hygiene.2,3,7 Urinary changes, as vaginal reflux, have been reported in most severe cases, although urinary retention is uncommon, since urine stream passage prevents labia adhesion in the urinary meatus area.

An expectant attitude should be adopted in most cases, especially if asymptomatic and involving a small labia portion, thus not interfering with urine flux. High rate of spontaneous healing (about 80% in one year) is usually observed.8

In case of symptoms or complications, first-line treatment consists of application of topical estrogen 0.01% cream three times daily, applied in the fusion line with a small and downward traction massage, until adhesion resolution (usually two to four weeks).6 Efficacy of this treatment is however debatable and probably higher in relapse prevention. Treatment is generally well tolerated and with mild side effects, such as local hyperpigmentation, vaginal bleeding, and rarely breast augmentation, which resolve with treatment discontinuation.9 Topical betamethasone 0.05% applied in two to three cycles for four to six weeks is an effective and well tolerated treatment, with some studies reporting at least identical efficacy to local estrogen therapy.10-11 Manual lysis is commonly performed under sedation, to avoid pain and psychological trauma, although it can be done with topical anesthesia if the child accepts and cooperates. Vaseline, estrogen cream, or local emollient application is recommended after mechanical adhesion resolution to reduce recurrence, which occurs in around 14% of cases.12

Hypertrophy/asymmetry of vaginal labia

Despite parents’ concern, in most cases this situation is a variant of normal.

It is usually a transient finding in the newborn (edema of the labia majora), resulting from fluid accumulation in tissues.

Hypertrophy of the labia minora can be associated with difficulties in genital hygiene, pain, or use of tight clothing. Reduction labiaplasty may be indicated in some cases, due to its important impact on quality of life, comfort, and self-image, but always after menarche.13

Clitoris hypertrophy

Clitoral hypertrophy may be related to fetal exposure to androgens, usually resulting from congenital deficiency of cortisol synthesis enzymes in the adrenals, such as 21-alpha-hydroxylase deficiency (adrenal hyperplasia) or tumor testosterone producer. Suspected cases should first rule out sexual differentiation disturbances,14 which require referral to specialized consultation for hormonal study.

Depending on hypertrophy degree, reduction clitoroplasty may be indicated.15

Congenital vaginal obstruction

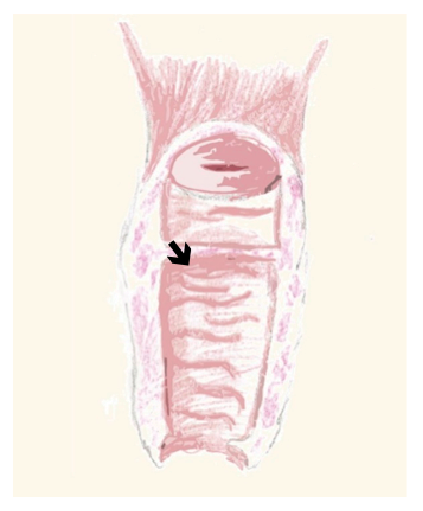

Congenital vaginal obstruction is often caused by imperforate hymen (0.5:1000) or more rarely by transverse vaginal septum (1:30000 to 1:80000) (Figure 2), in which case is frequently associated with Mullerian anomalies.16 Hemivagina obstruction by a longitudinal septum may also be present, a situation that may be associated with di-delphic uterus and unilateral renal agenesis (Herlyn-Werner-Wunderlich Syndrome).17

Diagnosis is difficult in the newborn, since an asymptomatic pattern due to mucus reabsorption is often the rule, and frequently goes unnoticed on physical examination of external genitalia.

This condition may present as interlabial cysts, especially if the obstruction is caused by an imperforate hymen, causing lower abdominal swelling.

Ultrasound is the exam of choice and diagnosis is often established at the time of menarche. By this time, blood accumulation is present in the vagina (hematocolpos) and/or uterus (hematometra), depending on the obstruction type and location. Primary amenorrhea occurs, as well as cyclic or continuous pelvic pain, and it is often possible to see an interlabial swelling or transverse septum on gynecological examination.18 CT or preferably MRI may be useful to characterize the vaginal septum and associated structural abnormalities of the reproductive and urinary systems.18,19

Excision or incision of the hymen or transverse septum is ideally performed prior to hematocolpos or hematometra development, but preferably after tissue estrogenization.20,21

Genital polyps

Vaginal and hymenial polyps are rarely observed.

This condition is characterized by growth of "fingerlike" fleshy fibroepithelial tissue in the vagina or hymen, sometimes accompanied by genital discharge, being rare in newborns.22 Without immediate indication for surgical correction, lesion biopsy or excision should be considered to exclude malignancy, namely rhabdomyosarcoma.23

Urethral eversion

Urethral eversion is a rare entity in girls and more frequently reported in the black race. It consists in eversion of a portion of the distal urethral mucosa through the external meatus, with a cleavage plane between the internal longitudinal and external circular-oblique smooth muscle layers of the urethra.24,25

Urethral eversion can occur with perineal hemorrhage due to vascular congestion of the spongy body and dysuria, and with eversion of the urethral mucosa on physical examination.

Topical estrogen twice daily for three to four weeks and two-week sitz baths may be effective in mild cases.26,27

Excision of prolapsed urethral mucosa and suturing of the remaining mucosa into vestibule is an option in more severe or nonresponsive cases.28

Vulvar cysts

Vulvar cysts are rare in pre-pubertal children and often require pediatric gynecology evaluation.

Skene cysts (para-urethral cysts) are retention cysts secondary to inflammatory obstruction of the Skene ducts (usually asymptomatic and regressing between the 4th and 8th weeks).29,30

Gartner cyst is a remnant of the Wolff duct, being most common in the lateral and posterior portion of the vagina.31

Bartholin gland cyst occurs when drainage from this gland is blocked, with subsequent inflammation.

Cysts are usually identified in physical examination and present as inter-labial masses.

Treatment is conservative in asymptomatic cases, requiring antibiotics in case of infection. Drainage/marsupialization/surgical excision may be indicated.32

Botryoid sarcoma

Botryoid sarcoma corresponds to an embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma subtype and is the most frequent neoplasia of the female genital tract in childhood, accounting for approximately 5% of all children malignancies.33

It presents as polypoid and multilobular, smooth-surface tumors often resembling a bunch of grapes, which protrude through the vagina and lead to abnormal vaginal bleeding and leucorrhea.34

The most common metastatic sites are the lungs, liver, and bone marrow.

Referral for biopsy and histological examination is paramount in this type of lesion, and treatment is individualized and consists of a combination of surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy.35

Prolapse of ectopic ureterocele

Ureterocele is a cystic dilation of the terminal ureter that can dictate varying degrees of ureteral obstruction, being more frequent in girls. It is termed ectopic ureterocele when prolapse extends from the bladder neck to the urethra.

Diagnosis is often established in prenatal ultrasound and can be associated with ureteral duplication, with frequent drainage of the superior renal pole.

Ectopic ureterocele may rarely cause bilateral urinary obstruction and may insinuate through the urethral meatus, thus becoming visible on physical examination of female pediatric patients.36,37

Treatment is surgical, with presence of lower ureteral reflux representing an important factor determining the approach.38-40

Conclusion

Anatomic genital pathology in prepubertal children is most often diagnosed by systematic and careful physical examination and in most cases has a very favorable outcome. Although these situations cause increased anxiety in parents due to their meaning, it is the physician's role to reassure parents and clarify the condition’s meaning. When necessary, implementing simple and feasible therapeutic measures in primary health care is often enough to solve the problem, which in many cases is self-limited.

It is also the responsibility of the family physician to identify situations which, due to their less favorable evolution, complexity, or potential functional or emotional impairment, require timely referral for specific diagnostic study, implementation of therapeutic measures, or even specialized surveillance.

In most cases, with implementation of the correct measures, prognosis of genital pathologies in the pre-pubertal child is favorable.