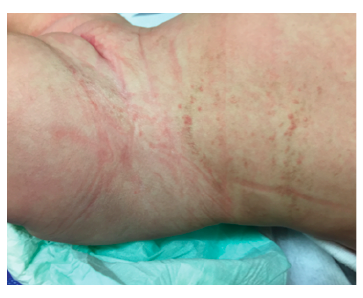

A four-month-old girl was observed at the Emergency Department due to an acute bacterial conjunctivitis. The patient had no other complaints and no relevant prior medical history. Physical exam revealed hyperpigmented macular lesions in the lower limbs (Figure 1) and hyperpigmented and papular lesions in the abdominal region, disposed according to Blaschko’s lines (Figure 2). The mother mentioned presence of cutaneous lesions in the same locations since birth, which progressively changed appearance and became hyperpigmented.

The child had normal growth, psychomotor development, and neurological examination. Family history was also unremarkable, with no parent displaying similar lesions.

The patient was referred to Pediatric and Dermatology consultations, with no skin lesion alterations after three months. At the age of 18 months, she attended a Neuropediatric consultation that showed normal growth and psychomotor development and no alterations on physical and neurological examination. Skin lesions were less pigmented and no new lesions were identified.

What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis

Incontinentia pigmenti (IP, MIM#308300).

Clinical diagnosis of incontinentia pigmenti (IP) was established and later confirmed by genetic testing, which identified a heterozygous IKBKG pathogenic variant with deletion of exons 4 to 10.

Brain magnetic resonance image (MRI) was requested, and the patient was referred to Ophthalmology, Stomatology, and Genetic Counseling consultations.

Discussion

Incontinentia pigmenti, or Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome, was first described in 1906. It is a rare X-linked genodermatosis, with an estimated incidence of one case per 40,000-50,000 newborns.1-4

IP is a neuroectodermal dysplasia affecting tissues embryologically derived from the ectoderm.2 It is a genetic disease inherited as an X-linked dominant trait, caused by a defect in the IKBKG/NEMO gene. The most common pathogenic variant is a recurrent exon 4 to 10 deletion, as in this case report. It is usually lethal in males (with the exception of cases of mosaicism, Kleinefelter syndrome (47,XXY), or hypomorphic mutations in IKBKG gene), while heterozygous females survive (due to functional mosaicism), accounting for 95% of living affected individuals.2,4,5 The disorder’s phenotypic expression is variable, ranging from very mild to severe cases.5

Clinical manifestations usually start at birth or early childhood.2 Regarding clinical findings, skin lesions are the sole major IP criteria and are present in all patients, displaying a specific pattern (along Blaschko lines), stage progression, and timeline. These lesions typically evolve through four stages, although lesions in different stages can simultaneously occur: (i) stage one (or vesicular stage) is identified in 90% of patients and characterized by linear papules and vesicles present at birth or within the first weeks of life; (ii) stage two (or verrucous stage) is identified by wart-like verrucous papules and keratotic patches and occurs within the first few weeks or months of life in 70% of patients; (iii) stage three (or hyperpigmented stage) consists in the development of linear or whorled hyperpigmentation lesions appearing in early infancy and slowly disappearing during adolescence and is observed in up to 98% of patients; and (iv) stage four (or hypopigmented stage) is characterized by patchy areas of hypopigmentation and cutaneous atrophy and is present in 75% of cases during adolescence, persisting into adulthood.2,3,6

IP differential diagnosis, based on dermatological findings, is extensive and depends on the stage of lesions.

Other organs may be affected in 70−80% of patients.6 Hair anomalies (alopecia, sparse hair, hypoplasia, or absence of eyebrows), nail alterations (yellowish pigmentation, dystrophy, or transverse or longitudinal slits), periungual and subungual keratotic tumors, and dental abnormalities (partial anodontia, hypodontia, delayed dentition, cone/peg-shaped teeth, impactions) are present in approximately 30% of IP cases. Breast and musculoskeletal abnormalities can also be present.2-6

IP females have heterogeneous and often severe clinical signs. Neurological defects (seizures, motor and mental retardation, microcephaly, brain ischemia) are present in 30% of patients, and ophthalmological anomalies (strabismus, cataracts, optic atrophy, retinal vascular pigmentary abnormalities, microphthalmia) in up to 70%. Eye and brain impairment are associated with significant morbidity and disability.2-6

IP clinical diagnostic criteria were proposed in 1993 and revised in 2014.7 If genetic testing is unavailable, presence of one major criterion or two or more minor criteria is necessary for diagnosis.7 Major criteria include presence of typical skin lesions in any of the four stages. Minor criteria include anomalies of the hair, nails, and teeth, retinal and extra-retinal abnormalities, alterations of the central nervous system, palate, and breast, and typical skin histologic findings.7

Clinical diagnosis can be confirmed by genetic testing, which also establishes the inheritance mode and allows for genetic counseling, when needed. Genetic testing and counseling enable prognostic evaluation, prenatal testing, and risk assessment for relatives4. Although expensive, it is readily available, has high sensitivity, and obviates the need for other invasive diagnostic tests, as skin biopsy.4

There is no cure for IP and treatment is limited to symptom management.2 As the condition can have multiorgan involvement, all cases should have a multidisciplinary approach involving Dermatology, Neuropediatrics, Ophthalmology, Stomatology, and Genetics.1-5 Brain MRI should be performed in all patients at baseline and repeated in cases of seizures, neurological abnormalities, or retinal neovascularization, since not all findings are present at birth. A thorough ophthalmologic examination must be performed early.2,3,5

With this case, the authors aim to emphasize the importance of a complete physical examination, as it has the potential to identify rare genetic conditions as IP. In the present case, a careful examination enabled lesion detection and clinical suspicion led to timely IP diagnosis in the child, prompting appropriate multidisciplinary follow-up.