Introduction

The present study started from a reflection on the potential benefit of identifying parental perceived self-efficacy (PSE) determinants, as it has been linked to a number of relevant parental and child outcomes.1,2 PSE can be defined as the level of confidence felt by caregivers during daily parenthood challenges. It can be usually classified in three distinct dimensions: task-especific, domain-specific, and general or broad, based on Bandura’s conceptual framework.3,4 According to previous investigations, it is an important determinant of positive parental behavior and hence of good development and child well-being.1,2,5,6 When looking at the underlying factors regarding PSE, there is considerable evidence of parental depression and infant behavior as two important variables inversely correlated in cross-sectional studies.7,8 Self-efficacy as initially conceptualized could be useful in parenting challenges, reciprocally interacting with performance. Although parental depression and measures of psychological well-being have been studied, there is a lack of information regarding each parent individually. Regarding fathers, much remains to be known about PSE during early childhood. Regarding mothers, an inverse relation has been shown between PSE and depressive and anxious conditions, as well as an insecure attachment pattern.7,8 From the toddler perspective, better adjustment capacity, greater enthusiasm, and less avoiding behavior and negativism have been shown in those taken care of by parents with higher PSE.2,7,8

The New Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood DC:0-5 pays particular attention to relational information (which can be included in a new Axis I diagnostic category) as a movement to better classify the network of close relationships surrounding the child.10 During clinical practice in a Child Psychiatry Unit, assessment of parental perceptions holds an important position, as it can influence not only behavior but also how relational experience is integrated. From this starting point, this study aimed to explore how parental beliefs could relate to their own psychologic well-being and explore the role of family interactions as a relevant mediator.

From the importance of a perception-mediated construct, this study sought to investigate the relevance of other perceptions potentially relevant for parents, namely parental support. Specifically, the study aimed to assess parental perceptions of mutual support and support from each parent’s family of origin, thus exploring horizontal relations within the family as a potential mechanism influencing vertical (parent-child) relations through association with PSE. More than quantifying help and behavior, the study’s main interest was to investigate how support is mentally integrated as a feeling or cognition, accessible through perceptions rather than through inventory and description of concrete actions. The hypothesis under investigation is the existence of a link between perception of mutual support or perception of support from the family of origin and parental PSE.

Materials and methods

Study design: Cross-sectional, clinical sample.

Sample: Parents of babies and toddlers assessed for the first time in an Early Childhood Child Psychiatry Unit.

Exclusion Criteria: 1) Children attending foster residential care or raised by other than biological or foster parents; 2) Death of a parent; 3) Physical abuse or any legal situation.

Data collection: Self-completed parental Parenting Sense of Competence (PSOC) scale (portuguese translation, reported internal consistency α=0.75-0.83) and two additional questions concerning perception of support from the other parent (SOP) and from the family of origin (SFO) completed at the end of the first medical appointment or at the beggining of the second one.

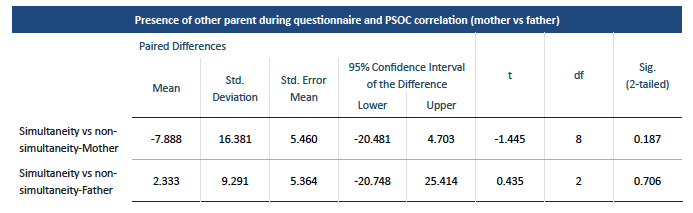

Presence of the other parent when completing the form was registered by the physician, in an effort to look at possible bias generated by inhibition or interference when declaring support perceptions. Two distincts situations were identified: simultaneity and non-simultaneity.

Assessment scale: Portuguese version of PSOC: Escala de Sentimento de Competência Parental - ESCP).11 Support perceptions were addressed through two additional questions also evaluated in a Likert scale concerning support perception from the other parent and from one’s own family of origin. Formulation of additional questions had a similar presentation to the original PSOC instrument: “I feel supported and understood by the father/mother of the child” and “I feel supported and understood by my family”. Answers were quantitative and dichotomous - negative from 1 to 3 and positive from 4 to 6.

PSOC is a self-reported questionnaire with 17 different items which allow to evaluate perception of general sense of competence in two main dimensions: self-efficacy and parental satisfaction, with reported Cronbach alpha values of 0.75 and 0.76, respectively. The scale has been redesigned to its current formulation by Johnston and Mash and does not include a cutoff threshold. It has been tested in the portuguese population, and a factorial analysis considering satisfaction, self-efficacy, and interest confirmed its validity.11

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® version 21. Inferential analysis was performed through t-test for unpaired samples and variable correlation was performed through Pearson r. The level of significance admitted in the presente study was 0.05.

Results

Descriptive analysis

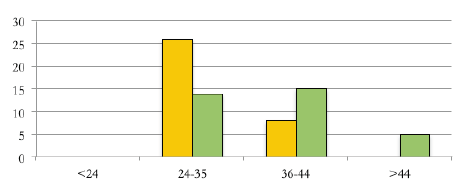

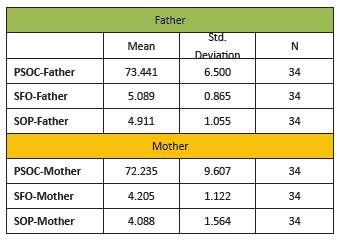

A sample of 34 correctly completed questionnaires was collected, with an average maternal and paternal age of 32.8 and 37.3 years, respectively. Regarding educational level, most parents had higher education (20 mothers and 18 fathers), followed by highschool (11 mothers and 11 fathers) and basic (three mothers and five fathers) education.

Inferential analysis

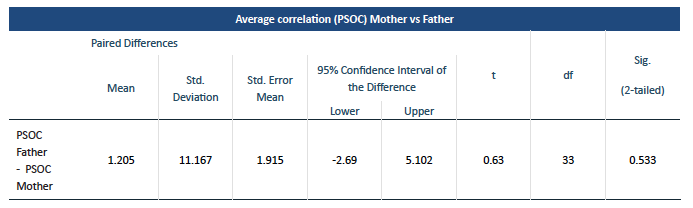

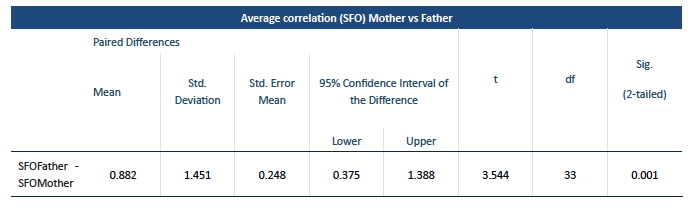

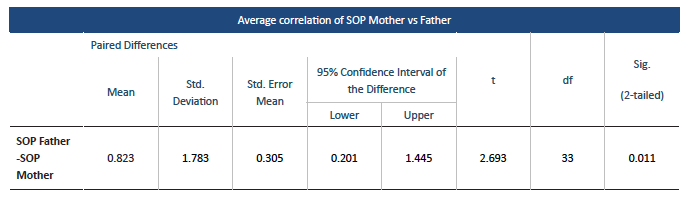

No significant differences were found between average PSOC in fathers versus mothers (73.44 vs 72.24, p=0.533). Perception of SFO in fathers achieved a superior average score than in mothers (5.09 vs 4.21, p=0.001). Perception of SOP in fathers was also higher compared to mothers (4.91 vs 4.09, p=0.011).

Table 1 PSOC (Parenting Sense of Competence), SFO (Perceived Support from Family of Origin) and SOP (Perceived Support from the Other Parent)

When analyzing presence of the other parent as an interference factor individually, mother’s PSOC did not significantly change when answering in presence of the father (simultaneity situation; 69.76 vs 76.11, p=0.187). Father’s average PSOC in presence of the mother also did not significantly change (73.16 vs 72.0, p=0.706). When analyzing simultaneity effect, neither parental PSOC reached statistical significance, despite a descending trend observed in mother’s PSOC in the simultaneity situation.

Results: Father

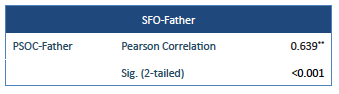

A positive correlation was found between PSOC and perception of SFO in fathers (r=0.639, p<0.01).

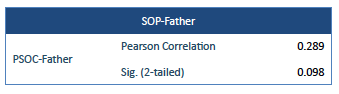

No significant correlation was found between PSOC and perception of SOP in fathers (r=0.289; p=0.098), as well as between perception of SOP and perception of SFO.

Table 4 Correlation analysis of Parenting Sense of Competence (PSOC) and perception of Support from Family of Origin (SFO) in fathers

Table 5 Correlation analysis of Parenting Sense of Competence (PSOC) and perception of Support from the Other Parent (SOP) in fathers

Results: Mother

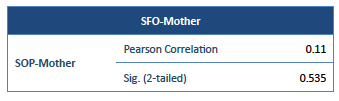

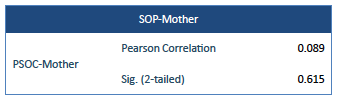

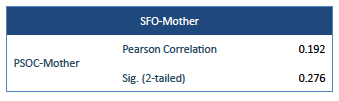

When analyzing maternal results, no correlation was found between PSOC and perception of SOP or SFO.

Also no association was found between perception of SOP and perception of SFO in mothers.

Table 6 Correlation analysis of Parenting Sense of Competence (PSOC) and perception of Support from the Other Parent (SOP) in mothers

Table 7 Correlation analysis of Parenting Sense of Competence (PSOC) and perception of Support from Family of Origin (SFO) in mothers

Discussion

As an overview, one might discuss how parental support perceptions could be integrated in the process of developing parental sense of competence. In addition to bringing some insights on how PSE could relate to caregiver’s horizontal network of significative relations, we included fathers in the study design, looking for differences in perceptions between both genders. The impact of family relationships on PSE remains understudied,2 and results from this study may indicate that it is important to separate relationships individually within the family (i.e. marital support and support from family) for environmental assessment, reinforcing the idea of different constructs.

PSE as a measure of parental satisfaction and efficacy is known to promote healthy development of babies and toddlers in the clinical setting. More than quantifying tasks, examining parental behaviors, or assessing marital status or general agreement concerning raising and educational issues, this study looked at perceptions, which can be regarded as one of the structural components of psychic life, called to act during parenthood everyday challenges. The present study does not seem to support an association between higher levels of PSE and more positive family functioning or greater marital satisfaction in the mother, as previously demonstrated.2

Considering the constant emotional interplay between a child and his/her caregiver during early childhood psychic development, it is acknowledged that relational quality and reciprocity could be easily influenced by the emotional status of the caregiver, as it will influence the child’s acquisition of new functional and emotional capabilities. Therefore, the required relational capabilities of the caregiver could in some way depend on the emotional availability from (or, more importantly, on the way it is perceived by) other relevant people with who he relates closer to. The relationship-based therapies delivered during some of our clinical interventions highlight the importance of emotions, not only expressed by the children, but also by caregivers, some of which are secondary to perceptions, cognitions, or beliefs regarding their own individual experience.

There is a growing body of literature focusing on coparenting and whole-family dynamics. Distinct patterns of triadic family interactions have been discerned and the coparenting construct itself can be seen as a specific form of triadic or higher-level family process early in the family life cycle.14 The role of the father within the triadic interaction influences the child’s well-being, not only through his own process of attachment, but also through cooperative and warm interactions, thus increasing coparenting quality.

According to Belsky’s conceptualization of parental behavior, this is the result of the interplay between the child’s temperament and gender, parental personality traits, and social contextual influences. At present, it remains unclear how PSE varies with environmental factors or gender.

When looking at the literature, personal determinants like depression and stress have been inversely correlated with maternal PSE.1,2 PSE may be sensitive to various contextual factors, without identifying family relationships as one of them.12 However, other authors suggest it could depend on the support and encouragement of one’s partner.3 The apparent conflicting evidence regarding mother’s PSE and environmental factors could result from a mostly internalizing functioning compared to fathers, reinforcing the idea of greater independence from outer compared compared with inner variables. In this context, studying parental perceptions could help to clarify the reach of a frequently projective description (towards the family of origin or other parent) regarding the cause of the child‘s difficulties/symptoms/needs or alternatively their own.

The authors’ expectation was to find differences according to the subpopulation of parents, since perception of support could be affected by emotional instability, conflict within the parental couple, or personality traits which could be tested in subsequent analyses. On the other hand, mothers rehearsing a symbiotic appeal or with a mainly fusional vertical relationship with their children usually perceive themselves as more competent. In situations of a burdening diagnosis on axis I, it could also contribute to a lower perception of parental self-efficacy, as previously suggested in the literature.1-8

Regarding gender differences, perception of SFO averaged higher in fathers than in mothers in this study. Additionally, perception of SOP was found to be higher in fathers. No differences were found considering PSE between parents, although theoretically the clinical environment and the fact that most children were boys could interfere with parental perceptions, mostly through the child’s behavior, as the literature finds mothers to rate themselves with lower PSE in a temperamental child.8 Our clinical population of parents, vulnerable by the burden of disease or infant condition, could easily face anxiety, depressive symptoms, or simply tiredness. Additionally, very heterogeneous clinical situations were behind each child psychiatry visit.

The correlation of father’s PSE with their family of origin is in line with existing data, since family environment has been considered a significant factor in father behavior and father-child relationship.13 That could add some insights on how within-family relationships influence men’s self-efficacy and parenting behavior.

Limitations

This study has some limitations that should be acknowledged, as the fact that the assessment was based on self-reported measures and the selection bias of the clinical population of parents enrolled, without sorting children characteristics, behavior, or temperament. Also, the study’s cross-sectional design does not allow causal interpretations. The fact that perception of support was evaluated with a quantitative and dichotomous question may have interfered with answering accuracy, since it implies judgment (although it was stratified in negative [1−3] and positive [4−6]). Although simply and directly formulated, this assessment method is not validated as a perception evaluating instrument. Also, although assumptions for the use of parametric tests (t-test) have been verified in the present study (i.e., normal distribution for samples < 30), the small sample size may have influenced the results obtained.

Conclusion

The initial purpose of identifying associations between parental perceptions and PSE was partially achieved, with a positive correlation between father’s PSE and perception of SFO. Regarding mothers, no significant correlation was found between PSE and perception of support, neither from the father nor from the family of origin. Mothers and fathers did not differ significantly concerning perceived self-efficacy.

Although perception of support from the other parent does not seem to correlate with PSE according to study results, considering the study’s limitations and reduced sample, further insights into gender differences are recommended to individualize clinical therapies.

Further studies are necessary to understand how father’s PSE could be influenced by relevant people with whom he relates closer to during the process of raising babies and toddlers in face of developmental difficulties, thereby adding valuable information when assessing relational context or wider psychosocial elements. In further studies, it could be interesting to correlate parental perceptions with child’s primary diagnosis.