Introduction

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute, self-limited vasculitis of small and medium arteries, with a predilection for the coronary arteries, predominantly occurring in young children.1-12 Untreated, it can lead to coronary artery (CA) ectasia, being the leading cause of acquired heart disease in developed countries.1-8

The condition’s etiology remains unknown and diagnosis relies on characteristic clinical features.5,6,8

It is important to recognize the early signs and symptoms of the disease in order to initiate intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) before the tenth day of illness and reduce the development of coronary abnormalities.3,4,8,10

Case report

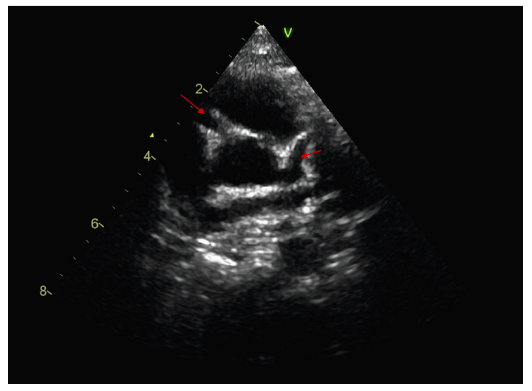

A previously healthy five-month-old boy was admitted to the Pediatric Critical Care Unit (PCCU) due to suspicion of sepsis/meningitis. He was transferred from another hospital where had been admitted for the last five days with a history of fever and cough, being diagnosed with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. The boy was previously healthy and had no recent travel abroad, animal exposure, or recent immunizations. His father had had acute tonsillitis and the five-year-old brother had a herpetic gingivostomatitis a few days earlier. Sequential onset of signs was reported before he was admitted to PCCU, including conjunctival injection, cracked lips, swelling of hands and feet, and polymorphous rash of the limbs. On the third day of hospitalization, clinical worsening was noted, with periods of decreased consciousness and signs of respiratory distress and need for oxygen. Electroencephalogram, brain computed tomography, and chest x-ray were performed, which revealed no abnormalities. Blood, urine, and liquor analyses showed leukocytosis with neutrophilia, elevated C-reactive protein, hyponatremia, hypoalbuminemia, elevated clotting time, sterile pyuria, and aseptic meningitis (negative cerebrospinal fluid culture, polymerase chain reaction for enterovirus, herpes 1 and 2, and streptococcus pneumoniae). Before the boy was transferred, broad-spectrum antibiotics, albumin infusion, and vitamin K were started and an echocardiogram was performed, revealing mild tricuspid insufficiency. On PCCU admission, the patient completed five days of fever and physical examination revealed an irritable infant with a temperature of 37.5ºC, elevated capillary refill time, poor general condition, dry, cracked and erythematous lips (Figure 1), swelling of extremities (Figure 2), and polymorphous rash of the limbs (Figure 3). Since he met KD criteria, IVIG 2 g/kg over 12 hours was started. After 48 hours, echocardiogram revealed ectasia of the left main coronary artery (LCA) (2.5 mm, Z-Score +2.6) and left anterior descending artery (LADA) (2 mm, Z-Score +2.4), CA perivascular brightness, mild pericardial effusion, mild mitral and aortic regurgitation, and normal left ventricular function and ASA 4 mg/kg/day was started. During hospitalization, albumin levels and clotting times normalized, and thrombocytosis developed (686.000/uL). Parvovirus, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, and Epstein-Barr virus serologies were negative. Immunoglobulin levels were within normal range. The ophthalmologic evaluation was normal. On the 9th day of hospitalization, fingertip and toe tip peeling were observed. The boy had good clinical evolution, with apyrexia after IVIG, and was discharge 11 days later with ASA. In a follow-up consultation eight days after discharge, he was readmitted due to worsening echocardiographic changes. Echocardiogram revealed major and diffuse ectasia of the right coronary artery (3 mm, Z-Score +4.8), LCA (3.5 mm, Z-Score + 5.7), and LADA (3 mm, Z-Score +5.7) (Figure 4). Electrocardiogram showed pathological 7-mm Q-wave in the inferior leads, but negative myocardial ischemia markers in blood tests. Double antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and ASA was started, together with a 3-day regimen of intravenous methylprednisolone followed by oral prednisolone for four weeks.

During follow-up, the patient displayed normalization of cardiac changes after five months and clopidogrel therapy was discontinued, maintaining treatment with ASA by the 9th month of follow-up. No further complications or readmissions were reported.

Discussion

KD was first recognized as a clinical entity in 1961 by Dr. Tomisaku Kawasaki.6,8 Incidence is higher in boys and is most common in winter and spring, as seen in the present case.8,12

The condition’s etiology remains unknown, but clinical and epidemiologic features suggest an infectious origin.7,8,13 One study showed that 8.8% of KD patients have documented respiratory viral infection.13 The study authors concluded that those patients had a higher frequency of CA ectasia and that the presence of concomitant viral infection should not exclude KD diagnosis.13,14 It should be noted that the present patient had a positive test for syncytial respiratory virus, being initially admitted for acute bronchiolitis, which delayed KD suspicion.

The classic KD diagnosis is based on a history of fever with five or more days of evolution associated with at least four of five clinical features: polymorphous rash, oropharyngeal mucous membrane changes, conjunctival injection, extremity changes, and lymphadenopathy.2,5-8,12,14 This patient met criteria for classic KD, except regarding lymphadenopathy, which is usually present in 50% of cases.12 A specific diagnostic test for KD is not available, but some characteristic laboratory features of the disease are identified, as leukocytosis with neutrophilia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, normocytic, normochromic anemia, thrombocytosis, sterile pyuria, hypoalbuminemia, hyponatremia, serum alanine aminotransferase level >50 U/L, plasma lipid abnormalities, and cerebrospinal and synovial fluid pleocytosis, most of which observed in the present patient.6,8,11,12Echocardiographic abnormalities supporting KD include CA aneurysm, Z-score of LADA or RCA of 2.5 or higher, pericardial effusion, mitral regurgitation, and decreased left ventricular function.6,8,11,12 Initial echocardiogram in the first week of illness is typically normal and does not rule out the diagnosis.12

According to North American recommendations, the primary treatment for KD is IV immunoglobulin and high-dose ASA (80-100 mg/kg/day).1,2,4,8,12 Japanese guidelines suggest lower ASA doses (30-50 mg/kg/day) and a recent study showed that there was no difference in the risk of CA abnormalities in the low-dose compared with the high-dose ASA group, concluding that a dose between 3 to 5 mg/kg/day may be indicated in acute KD.4 In the present case, low-dose ASA (4 mg/kg/day) was used, with good results. Corticosteroids may be added to the primary treatment in high-risk patients (IVIG resistance and/or evolving CA aneurysm), in order to prevent CA aneurysm progression.1,8,12 In this case, given CA ectasia worsening, the option was for three days of intravenous methylprednisolone followed by a long oral prednisolone taper, with good clinical outcome.

Management beyond the acute stage consists in regular echocardiography, given the risk of aneurysm development, especially in the subacute stage.8,12 CA aneurysms or ectasia occur in 15% to 25% of untreated children and in less than 5% if treatment is started within the first ten days of fever. 5,12,14 Myocardial infarction is the most common cause of death, and usually occurs in the first year after diagnosis.8,12 After stabilization of cardiac changes, a six-to-twelve-month echocardiographic follow-up is performed in several centers.8,12

KD is an acute and self-limited disease, but cardiac abnormalities that develop may be progressive and children’s prognosis is determined by the degree of cardiac involvement and sequelae.8,12 Most children present resolution of aneurysm or CA ectasia in the first two years of disease, with worst prognosis occurring in children with giant aneurysms. 12

Recurrence may occur in 2% to 4% of cases and is more common in children younger than three years.12 In the present patient, normalization of cardiac abnormalities after five months suggested a likely favorable prognosis.

In conclusion, this case report suggests that KD should be considered in infants with concomitant viral infection and initial normal echocardiogram. Recognition of KD clinical criteria associated with laboratory findings are of paramount importance in these patients’ prognosis, as early treatment is associated with fewer cardiac complications.