Introduction

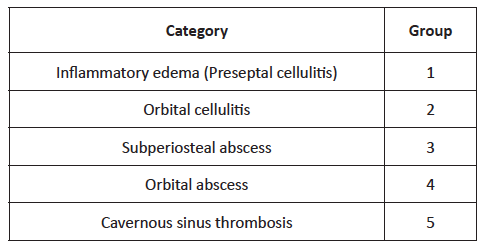

Acute sinusitis is responsible for up to 82% of cases of orbital infection. (1 Before the widespread use of antibiotherapy, 17% of patients affected by orbital cellulitis died from meningitis and 20% suffered permanent visual loss. (2 Orbital complications can occur either directly through a defect in the lamina papyracea or from an septic emboli. (3 Diagnosis is usually established through the combination of clinical examination and radiologic findings. (4 Chandler’s classification (Table 1), published fifty years ago, still represents the most complete and popular classification of orbital infection severity. (5

The best pharmacological modality for these patients remains controversial, and the optimal surgical approach has been debated, especially since the widespread use of endoscopic nasal surgery. (6 The aim of this study was to analyze the outcomes of patients admitted to the Department of Otorhinolaryngology of our institution with orbital complications due to acute sinusitis over an eight-year period.

Material and methods

A retrospective review of medical records of all children (age <18 years) diagnosed with orbital complications of acute sinusitis admitted to our hospital department between 2010 and 2017 was conducted. Data retrieved included demographics, clinical signs and symptoms, laboratory study, radiologic evidence of orbital inflammation and sinusitis, treatment with intravenous antibiotic, and surgical intervention.

Stata® 15.0 was used for data descriptive and analytical statistics. Associations between dichotomic variables were assessed with chi-squared test (or Fisher’s exact test, when applicable), and continuous measures were compared using a two-sample student t- test. Statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Results

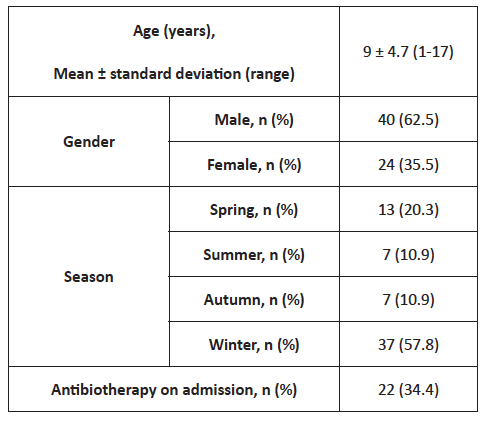

A total of 64 children were admitted to our institution between January 2010 and December 2017, with a mean age of 9 ± 4.7 (range 1-17) years and predominantly (62.5%) male. Most patients were admitted during winter months (57.8%) and 65.6% were not under any medication on admission (Table 2).

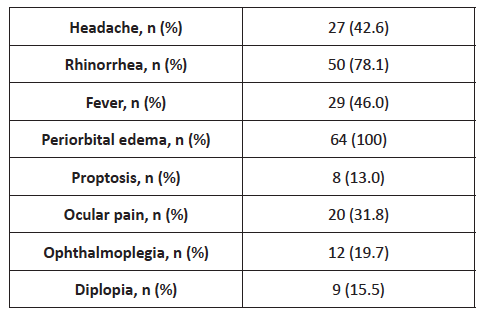

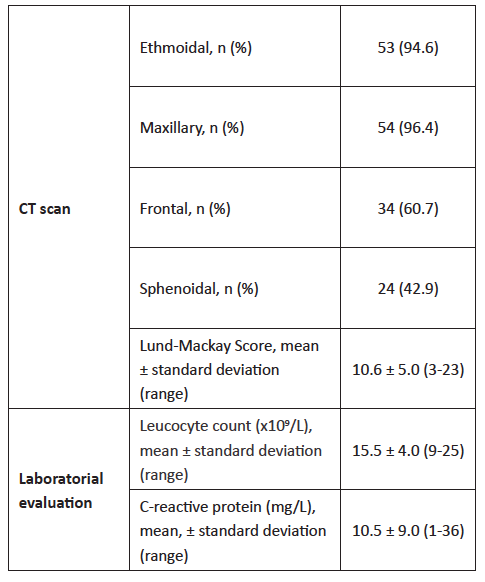

Clinical findings are resumed in Table 3. Most patients were admitted with rhinorrhea (78.1%) and only 46% presented with fever. Patients with rhinorrhea tended to be admitted earlier to the Emergency Department compared with patients without this symptom (2.6 vs. 4 days, respectively; p=0.05). Ocular signs were uncommon, with ocular pain being the most relevant ophthalmologic sign (31.8%), followed by ophthalmoplegia, diplopia, and proptosis. Computed tomography (CT) scan was performed in 65 (87.5%) patients, with ethmoidal and maxillary being the most commonly affected sinuses (95.6% and 96.4%, respectively; Table 4) . Frontal disease was more prevalent in older patients (11.0 ± 4.0 vs. 7.9 ± 4.2; p=0.01). Lund-Mackay score was used for sinusitis radiologic staging, showing a mean value of 10.6 ± 5.0 (range 3-23) and inverse correlation with age (p=0.01). Most (53.8%) patients with proptosis on admission presented abscesses in CT scan (p=0.001). Laboratory findings showed a mild rise in white blood cells (15.5 ± 4.0 x 109/L) and C-reactive protein (10.5 ± 9.0 mg/L; Table 4).

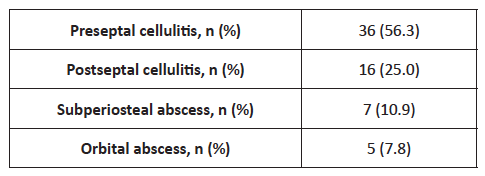

Cellulitis was the most prevalent complication in this patient population (Table 5). Thirty-six patients (56.3%) developed preseptal (Chandler type I) and 16 patients postseptal (Chandler type II) cellulitis. Overall, 12 patients (18.8%) presented subperiosteal (n=7) or orbit (n=5) abscesses. Two patients with orbital abscesses developed intracranial complications: cerebral abscess in one patient and cavernous sinus thrombosis in another patient.

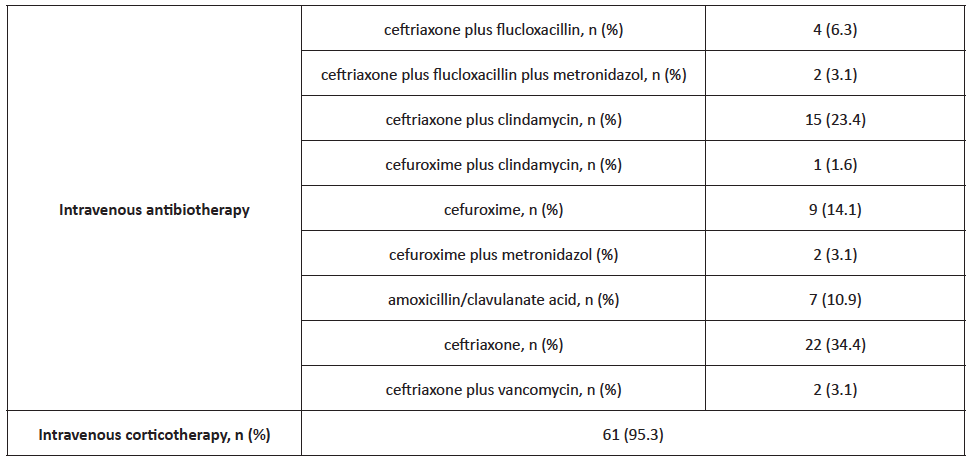

Treatment predominantly included high doses of intravenous ceftriaxone combined with other drugs (flucloxacilin, clyndamicine, or metronidazole; Table 6). Sixty-one (95.3%) patients received concomitant intravenous corticotherapy. Patients exclusively treated with medical therapy had a lower mean age (8.75 ± 4.8 years; p>0.05). Only four patients, with a mean age of 12.8 ± 3.0 years, required surgical drainage, three of whom with external approach and one with combined approach. Two of these patients presented positive culture, one for Fusobacterium necrophorum and the other for Streptococcus constellatus. The mean length of hospital stay was 8.0 ± 5.5 days (range 2-38), and was longer in patients submitted to surgery (11.3 ± 2.9 vs. 7.8 ± 5.6 days in patients undergoing pharmacotherapy, p >0.05) and in older patients (R=0.2546, p= 0.04).

Seven patients (10.9%) recurred shortly after hospital discharge (mean 10.6 ± 7.3 days) due to relapse of orbital signs and were submitted to a longer period of parenteral antibiotherapy, with full recovery. Programmed adenoidectomy was performed in two of these patients (with five and eight years, respectively), and functional endoscopic sinus surgery was performed in a 13-year-old patient to improve nasal breathing.

Discussion

Ethmoid sinuses are separated from the orbit by the lamina papyracea, a paper-thin layer that contains many perforations for nerves and blood vessels, as well as some natural dehiscences. (7 Ethmoidal and maxillary sinuses are usually the only cavities present in childhood, and complicated sinus infections mainly result from disease in these sinuses. The orbit is a cone-shaped structure lined by periosteum and surrounded by paranasal sinuses. The orbital septum is a thin connective tissue membrane that separates the superficial portion of the lids (preseptal region) from the deeper orbital structures (postseptal region). Preseptal infection usually only results in cellulitis. However, postseptal infection can evolve from cellulitis to an abscess collection, either intraconal (orbital), extraconal (SPA), or intracranial (directly or through cavernous sinus thrombosis). (8)-(9 Sinus involvement and orbital extension can be difficult to predict based only on clinical examination, and account for the high number of patients (87.5%) evaluated with CT scan in the present study. Patients in this retrospective cohort were slightly older (mean age of 9 ± 4.7 years) compared with other studies, (1), (10), (11), (12), (13 what may explain the high prevalence (60.7%) of frontal sinus involvement found. In agreement with the results obtained, other authors have also reported a strong statistical correlation between ophthalmoplegia and proptosis and presence of orbital abscesses. (1), (2), (7), (12 Gonçalves R et al. investigated a group of 110 children and found that ophthalmoplegia (p <0.001) and proptosis (p <0.001) were significant features for post-septal infections. (7 Although abscess volume was not measured in the present study, bigger abscesses are more prone to surgical drainage, with abscesses larger than 1.250 mm3 likely requiring surgical drainage, according to Todman MS and colleagues. (12), (13), (14), (15

Management of these patients remains a critical issue. Several studies reported a high percentage of patients successfully treated with medical therapy only, (4), (11), (14), (16), (17 in agreement with findings from this study. Parenteral therapy should include broad-spectrum agents, with some authors recommending maintaining it for up to 2-3 weeks. (18 Itzhak Brook recommended an association with a beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor (e.g., ampicillin-sulbactam, amoxicillin-clavulanate, piperacillin-tazobactam), a carbapenems (e.g. imipenem, meropenem), or a third-generation cephalosporin (e.g. ceftriaxone, cefotaxime) and metronidazole or clindamycin to cover anaerobic bacteria. (19 In this study, patients were preferentially treated with high doses of ceftriaxone, associated with metronidazole or clindamycin in cases of high suspicion of abscess.

Improvement can be assessed by clinical (decrease of ocular edema, erythema, and discomfort) and laboratory progress, with serial CT scans not recommended, for not being a reliable indicator of clinical improvement. (5), (9), (12 In this study, all patients requiring surgery were above nine years of age. However, results in the literature remain inconclusive regarding age as a potential risk factor for surgical therapy. The odds ratio for requiring surgical treatment increase by 1.5 with each year of age above 5 (p=0.004, 95% CI 1.33-1.89), according to a study by Ryan J et al. (14), (17 However, another study reported that age was not a predictor of surgical intervention, (13 in agreement with results from the present study. Sciarretta et al. proposed that surgical treatment should be guided by Chandler system score (Table 1), as stage I and stage II are usually best managed with medical therapy and other stages usually require surgical approach to clear the purulent collection. (1 Regular evaluation of these patients is critical, as failure to improve after the first 48 hours likely reflects treatment failure and need for surgical intervention. (2

Conclusion

This eight-year experience indicates that early diagnosis and prompt institution of appropriate intravenous antibiotic therapy in hospitalized children with orbital complications of acute sinusitis can lead to favorable clinical outcomes without surgical intervention in most children. All patients should be closely monitored with serial ophthalmologic examination, and any deterioration should lead to timely drainage.