Introduction

Pediatric Palliative Care (PPC) encompasses an active and global approach to the care of children and young people with life-limiting or life-threatening conditions (LLC or LTC), from the moment of diagnosis or recognition and throughout the child’s life until potential death and beyond. It embraces physical, emotional, social, and spiritual elements and focuses on enhancing the quality of life of the child/young person and supporting the family. (1 Conditions in PPC can be grouped in four broad categories: (i) LTC for which there is curative treatment, but it can fail (e.g., cancer, irreversible organ failure of the heart); (ii) LLC with inevitable premature death (e.g., cystic fibrosis, muscular dystrophy); (iii) progressive LLC without curative treatment options (e.g., Batten disease); and (iv) non-progressive, irreversible LLC associated with severe disability, health complications, and premature death (e.g., cerebral palsy). (1 Pediatric conditions requiring palliative care are known to impact the family network. (2), (3 Coupled with the threat of premature death, the emotional impact on the family of a lifetime diagnosis in a child is profound. (4 Furthermore, the demands of treatment may be highly disruptive, not only to parents but also to siblings at home. (5 As a result, the family-centered approach in PPC should seek to maintain the integrity of each individual and family as a whole, providing guidance and support through the entirety of child medical care, from diagnosis to end of life and bereavement, and allowing time to prepare for impending challenges. For that purpose, understanding the needs of each family member, including siblings, is fundamental. (3), (6

According to previous studies, siblings of children with cancer do not consistently show elevated rates of psychopathology, but they do have psychosocial needs that should be recognized and addressed, such as loss of needed attention and threatened sense of security within the family. (7), (8 The demands of caring for a child with cancer often limit «parents’ physical and emotional availability to fully attend the needs of other children». Consequently, recommendations indicate that the extended family, health care professionals, siblings’ school staff, and relevant community members should consider the unique needs of siblings, in addition to the needs of the family in general and the health of the child with cancer. (7 Moreover, studies investigating the psychological functioning of siblings of children with chronic illnesses also show a risk of negative psychological effects, demanding intervention programs. (8

Accordingly, support for siblings in PPC setting is widely recommended. (1 This support should include the identification of increased needs and access to more specialized support when required, assuming that most siblings will cope with upcoming challenges if the appropriate support is given. Bereavement support should also be provided to all children and young people experiencing the death of a sibling. (1 However, sibling support is still an emerging area, and proposed recommendations are based on clinical experience and adaptation from specific settings, as Pediatric Oncology or chronic diseases. (7), (8 In fact, although a variety of tools have been developed to assess the needs of caregivers of adult palliative patients, few are in place for siblings of patients in PPC. (6 Overall, there is a lack of primary research on the needs and concerns of siblings of children in PPC. Additionally, no reviews on the topic have been found in a preliminary search in Medline.

The aim of this scoping review was to assess and describe the needs and concerns of siblings of children in PPC, as a greater understanding of this subject may lead to improved sibling support and, eventually, more specific clinical recommendations.

Methods

A scoping review was performed based on the methodological frameworks proposed by Arksey and O’Malley9 and Joanna Briggs Institute. (10 First, the research question was defined: “What should a young researcher in Pediatric Palliative Care know about the needs and concerns of siblings?”, pinpointing participants (siblings), concept (needs and concerns), and setting (PPC).

The literature search was conducted in Medline database until December 31, 2020, using the following queries: 1) ("Siblings"[Mesh]) AND ("Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing"[Mesh] OR "Palliative Medicine"[Mesh] OR "Palliative Care"[Mesh] OR "Hospice Care"[Mesh] OR "Terminal Care"[Mesh] OR "Hospices"[Mesh]); 2) children palliative care siblings. The search strategy was limited by publication date (2000-2020) and language (English or Portuguese).

The following inclusion criteria were used: 1) research articles; 2) studies related to PPC; 3) studies having siblings themselves as study participants (as the evidence shows that children’s perspective on their experiences offers useful augmentation to parental proxy reports, which may obfuscate some of the more sensitive issues and opinions); (2 4) studies with siblings in the pediatric age range at the time of diagnosis. Exclusion criteria applied comprised: 1) studies related to adult Palliative Care; 2) studies whose participants were not siblings themselves (but instead parents, health professionals, etc.); 3) studies not exploring the needs and concerns of siblings in PPC; 4) studies with no abstract available; 5) review articles.

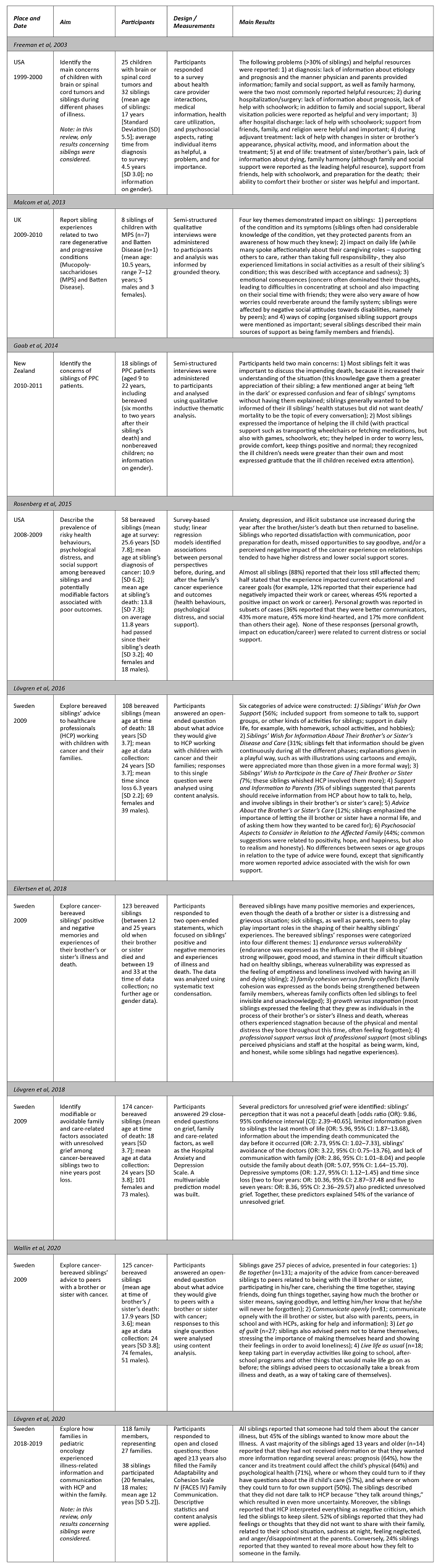

Data about place and date, aim, participants, design/measurements, and main results were retrieved from studies included in the analysis and narratively described.

Results

The literature search retrieved 151 citations. After exclusion of duplicates, 131 articles were screened for eligibility, resulting in the further exclusion of 122 articles. In the end, nine articles were fully assessed and included in the analysis.

Data are summarized in Table 1. Studies included show that perceptions of the condition of the ill child and his/her symptoms, impact on daily life, emotional consequences, and way of coping seem to be key issues for siblings of children in PPC. (2 Particularly, siblings report the need for their own support, (11 referring engagement in the exchange of information and in care of the brother/sister as relevant to them. (6), (11), (12 Siblings also report insufficient or poor information regarding the ill child’s prognosis and psychological health outcomes, but also where to seek support for themselves. (13 Siblings’ needs vary across the course of the disease: the most common problems are initially centered in deriving information to understand what is happening and why, in trying to keep up with self responsibilities (schoolwork) afterward, and in learning to cope with changes in the ill brother/sister in later stages. Regarding end-of-life, relevant concerns experienced by siblings include pain palliation, the ability to provide comfort to the brother/sister, the need to obtain information about death, preparing for death, and obtaining social support and family harmony. (4 Bereaved siblings of cancer patients are generally resilient and, although risky behaviors and psychological distress increase during the year after the brother/sister’s death, most return to baseline over time. Siblings who report dissatisfaction with communication, poor preparation for death, missed opportunities to say goodbye, and/or perceived negative impact of the cancer experience on relationships tend to have higher distress and lower social support scores. (5 Furthermore, siblings’ perception of a nonpeaceful death and avoidance of physicians, poor medical information, and poor communication about the brother/sister’s death with family and friends predicted unresolved grief two to nine years post-loss. (14 On the other hand, supporting the siblings of children with cancer throughout the cancer journey and afterward into bereavement has shown to have a positive buffering effect on their own endurance and personal growth, family cohesion, and social support. (15

Discussion

Results of this study indicate that there is room for improvement in the support to siblings of children in PPC11), (13), (15 in various dimensions (informational, instrumental, appraisal, and emotional) and throughout the course of the disease. (4 Informational support should be tailored to siblings in a developmentally targeted manner5 and include the description of the disease and possible side effects of treatment that may involve changes in the appearance and level of activity of the affected child. Most importantly, health care providers should emphasize that siblings had no role in causing the disease. (4 Additionally, siblings may benefit from being prepared for the death of the brother/sister and from having the opportunity to say goodbye. (5 In fact, the International Society for Paediatric Oncology guidelines for the support of siblings of children with cancer16 advise health care professionals and parents to involve siblings from the time of diagnosis, keeping them informed. (4), (11), (16 As shown by Roseberg et al., a period of great vulnerability seems to exist during and immediately after the illness (or death) experience. Sharing information during this time may be challenging for parents, with most seeking to protect their children from difficult information. (5 Additionally, staff overidentification with parents’ needs to protect the sibling often leads to a lack of information. Consequently, these siblings often have mistaken ideas regarding the disease, (4 which may ultimately hamper the bereavement process, (5 leading to unresolved grief. (14 Actually, the consequences of talking to siblings about sensitive issues are likely to outweigh the costs of remaining silent. (6 Caregivers who are apprehensive about involving siblings should be explained that being involved in the care of the ill child and having conversations about his/her general health status are generally viewed as important by the siblings themselves. (6 In the study by Freeman et al., one of the most helpful resources identified by siblings was the ability to visit the hospitalized child when desired. According to the authors, visiting allows the sibling to directly observe how the ill brother or sister is doing medically and the type of treatment and care provided, promoting the reality of the situation and positioning the sibling to interact with health care providers for the acquisition of information. Additionally, visiting likely involves other family members, which may foster feelings of family cohesion. (4 It is also important to be aware of how siblings engage in protective buffering. Consequently, professionals need to assess siblings’ level of knowledge of the condition and its impact directly from the child, rather than from parental proxy reports, which may underestimate the impact on siblings. (2 Siblings also need instrumental support, especially as the disease progresses and they tend to return to their own concerns, requiring parental attention. (4 In the study by Lövgren et al. (2016), more than half of siblings suggested advice related to their own need for day-to-day support from diagnosis to several years after bereavement. (11 Also, in the study by Wallin et al., siblings advised peers to occasionally take a break from illness and death as a way of taking care of themselves. (12 Accordingly, studies in pediatric cancer setting show that minimal gestures, such as asking healthy siblings how they are doing (instead of asking about the child with cancer) or providing them with individual attention concerning their interests, may be beneficial and appreciated. (7 It may be important to increase support for siblings from their extended family, school, and community members, by raising awareness of the situation of the healthy sibling in these groups. (7), (11 Siblings may also benefit from appraisal support, including instruction in coping strategies to deal with changes of the affected child and engagement in his/her actual care and comfort. (4), (15 With open, transparent, directive instructions on how to care for their brothers/sisters and family in general, siblings may engage in helping behavior, fulfilling their cognitive and active coping styles. (6 Additionally, this may in turn promote strong family cohesion, thus contributing by helping bereaved siblings to create more positive experiences with and memories of the sick sibling. (15 This has been previously recommended for siblings of children with cancer, with advice for the Oncology team to include siblings in treatment, as appropriate (e.g. giving tours of the hospital ward; explaining tests, procedures, and treatments), as this may help siblings feel more included and less isolated. (7 The need for emotional support can be addressed with support groups during hospitalization, throughout treatment4 and, importantly, after the child’s death. (5 Health professionals have an active role in this domain, since they must mediate hope in a realistic and honest way. (11 It is important to adopt a systemic approach to better understand the mutually reinforcing relationship between the family and wider environment on sibling adjustment. (2 This review parallels previous findings in siblings of children with cancer, where higher levels of distress were more common within two years after diagnosis, with most siblings responding well with minimal support. As in Oncology setting, (7 it seems reasonable to recommend that those who display significant distress should be referred to evaluation and treatment by mental health care specialists.

Although seven studies included in this review refer to the Oncology setting, siblings’ needs may vary substantially, (6 as PPC patients have a great diversity of medical conditions, with very different trajectories and prognosis, making generalizations from disease-specific studies inappropriate. For example, for siblings of children with progressive LLCs, the ongoing deterioration of the child’s condition requires that support be flexible enough to respond to changes, symptoms, and relationships, to provide the best care to siblings. (2 In fact, previous studies show that chronic illnesses with daily treatment regimens are associated with negative effects compared to chronic illnesses that do not affect daily functioning. (8

Five of the nine studies included in this review focused on the bereavement stage. However, as previously described, PPC encompasses a far broader and earlier approach than solely bereavement support. (1 Therefore, future research should focus on the needs and concerns of siblings in PPC using an earlier and longitudinal assessment. It should also be noted that the exclusion of studies in which participants were not the siblings themselves, although informed by evidence showing that siblings’ own perspectives provide beneficial augmentation to proxy reports, (2 may have omitted research articles concerning younger siblings - a population that requires special attention and care.

Conclusion

Siblings of children in palliative care have the need for information, engagement in brother/sister’s care, and psychosocial support. In the future, quantitative studies of siblings’ wishes may enable a more effective assessment. (6 Prospective studies in which siblings are interviewed as they go through the different stages of disease should be performed in order to evaluate their perspectives, experiences, and outcomes. (4), (5 Clinical practice recommendations should also be developed, taking into account the general principles of palliative care but also leaving room to include the specificities of each disease course and, most importantly, the uniqueness of each child, family, and sibling.