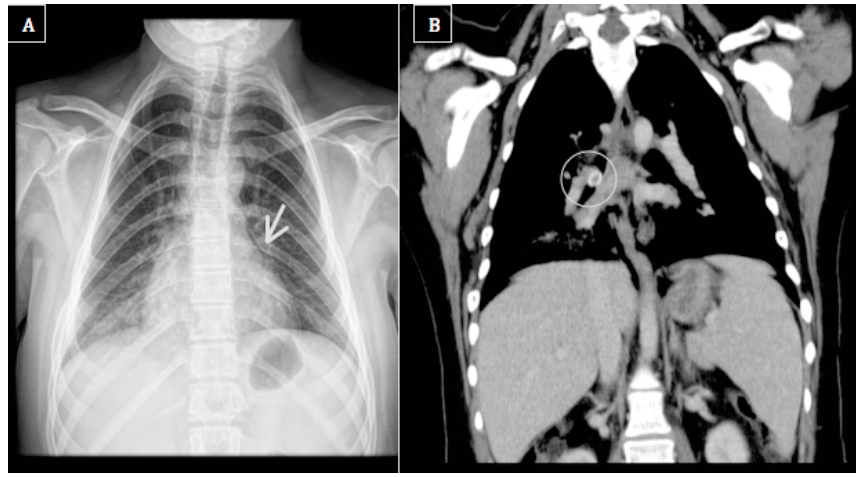

A 15-year-old female teenager with Chiari type I malformation (a pathogenic microdeletion of the chromosome 16 ─ 16p13.11 microdeletion syndrome ─ associated with global development delay) presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with a history of fever with 24 hours of evolution. She had choked with an olive pit the day before, saying that it was spontaneously expelled through coughing. Despite the absence of respiratory signs or symptoms and possible non-radiopaque nature of the foreign body, expiratory chest radiograph and abdominal x-ray were performed, showing no changes, and the girl was discharged with the probable diagnosis of viral infection. Eleven days later, she returned to the ED with persistent fever, dysphagia, and productive cough with hemoptoic sputum. On admission, she presented nasal obstruction and crackles and decreased lung sounds on the right hemithorax. No hypoxia, respiratory distress, or expiratory stridor were identified. Laboratory assessment revealed leucocytosis (14,670/μL) with neutrophilia (11,190/μL) and increased C-reactive protein (250 mg/L), and chest x-ray showed a small-volume pneumomediastinum and a less prominent right cardiac silhouette, suggesting condensation on the right lower lobe (Figure 1A).

What is your diagnosis?

Discussion

In the present case, chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed an obstruction of the bronchus intermedius by a foreign body (Figure 1B). Rigid bronchoscopy was later performed with extraction of an olive pit. The patient had favorable clinical outcome after a full 10-day treatment course with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid and prednisolone.

The clinical findings, complementary exam results, and favorable outcome in this case confirmed the diagnosis of foreign body aspiration (FBA) with pneumonia.

FBA is a relevant concern in pediatric age, particularly in children under the age of five years and in vulnerable children, like those with global development delay or neuromuscular disorders.1-5 The girl in the present case had Chiari type I malformation and 16p13.11 microdeletion syndrome, with global development delay, thus having a high risk of FBA.6 Besides potentially life-threatening, FBA can remain undetected due to absent or atypical history and misleading clinical and/or imagiological findings. It is not uncommon to find patients treated for suspicion of other disorders, such as infectious diseases, asthma, or psychiatric conditions.2 A high index of clinical suspicion, combined with accurate history, with or without abnormal radiological features, is mandatory to recognize this entity and prevent delayed diagnosis and complications.1,2

Clinical symptoms are associated with the patient’s age, size, location, and type (organic, inorganic) of foreign body, and time elapsed from the moment of aspiration until presentation. The most common complaint is sudden onset of cough, which can present with wheezing and/or signs of respiratory distress. For patients who delay seeking medical support, fever, flank pain, crackles, and diminished breathing sounds may be observed, similarly to the present case.1-4 Recurrent pneumonia, that occur in the same anatomic location, can also be a form of presentation. Foreign body extraction is crucial for successful treatment.

In the first hours, local hyperinflation at the affected side represents an indirect radiological finding potentially suggestive of FBA. Later signs include pleural effusion and/or consolidation. However, all of these are nonspecific.1,4 Importantly, the absence of pulmonary signs on chest x-ray should not rule out FBA, since at least 90% of foreign bodies are non-opaque. Consequently, it is crucial to determine whether the patient should undergo additional imaging exams, as CT scan or bronchoscopy, based only on the possibility of aspiration. CT scan might help in cases with atypical presentation or radiologic findings, as the differential diagnosis includes tracheobronchial obstruction caused by external compression (e.g., tumors, cardiac enlargement) or intraluminal obstruction (e.g., granulomatous tissue, cystic fibrosis, asthma).2,4 Due to radiation exposure and possible need for general anesthesia, there is conflicting evidence in the literature regarding the benefit of performing CT scan before bronchoscopy. Nevertheless, CT is a non-invasive, feasible, and reliable imaging technique that can prevent unnecessary endoscopic procedures under general anesthesia.5 It can be performed with intra-rectal/nasal midazolam administration and a tolerable amount of radiation nowadays.5 Still, rigid bronchoscopy remains the gold standard, as it enables not only a definite diagnosis but also extraction of the foreign body(ies) and oxygen administration.4

In conclusion, every parent should be aware of early symptoms of FBA, as most events occur with no witnesses. Also health professionals should maintain a high index of suspicion, especially in cases with atypical history and nonspecific imaging findings. Additional imaging exams and rigid bronchoscopy should be used to confirm FBA diagnosis and treat the condition, crucial for a favorable clinical outcome.