Background

The first cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) were reported in December 31, 2019, with its causative agent ─ severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) ─ soon identified. One month later, in January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern. The disease quickly spread beyond control, overwhelming health care systems and economies on a global scale, and in March 11, 2020 WHO formally attributed COVID-19 the pandemic status.1

In the first couple of months, the incidence of cases and deaths was low, and the consequences of the disease were modest in Portugal. However, COVID-19 subsequently became a major national concern in the following pandemic waves, with Portugal even leading world country in new cases and deaths per million people for a short period of time.2

The burden of COVID-19 has been less significant in the pediatric compared to the adult population, with children accounting for approximately 15% of the total number of cases reported to date.3) In addition, the severity of symptoms and mortality associated with the disease are reported to be much less severe in younger patients, who show an overall asymptomatic rate ranging from 15 to 42% and an overall mortality rate lower than 0.1% (compared to ≈2% in adults).4,5

Due to the clinical course of the disease, it was reasonable to promote close symptom surveillance at home for children who did not fulfill criteria for immediate hospitalization. In our center, daily follow-up by telephone was secured to all pediatric COVID-19 patients during the isolation period (10-20 days), with monitoring of patients’ clinical evolution and drug use and advise for medical assessment when necessary . With this close approach, it was possible to track disease symptoms and evolution in an accurate way, allowing to draw conclusions regarding its management and prognosis.

The present study aimed to investigate COVID-19 manifestations in the pediatric population, based on the experience with patients followed at our center.

Material and methods

A retrospective descriptive and analytic cohort study of children with positive nucleic acid amplification of SARS-CoV-2 by real-time-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) after nasopharyngeal swab was carried at our tertiary pediatric center between March 2020 and September 2021. Patients from 0 to 18 years old with a positive RT-PCR test performed in the setting of Emergency Department (ED), hospitalization for any medical reason, or prior to elective surgery at our institution were included, as well as patients followed in regular medical appointments at our center who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 elsewhere. Cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) associated with COVID-19 were excluded.

The national Portuguese Directorate-General of Health (DGS) guidelines for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR testing in ED were followed. Suspicious cases eligible for testing included patients with at least one of the following symptoms: cough, fever, respiratory distress, anosmia, and/or dysgeusia. In children presenting with at least two other disease symptoms (namely nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal pain) or with a known epidemiological link, the decision for carrying out SARS-CoV-2 testing was made on a case-by-case basis.

Data collected included patients’ age, gender, and chronic conditions, presence of an epidemiological link, symptoms, need for medication, number of days with symptoms, and disease severity. The number of patients who required emergency referral or hospitalization after initial discharge was also retrieved.

COVID-19 was classified according to severity in (i) asymptomatic (positive test but absence of symptoms); (ii) mild (presence of mild symptoms, such as short-term fever, cough, or rhinorrhea, without respiratory distress, dyspnea, or abnormal chest imaging); (iii) moderate (clinical or radiographic lower respiratory disease with oxygen saturation ≥94% on air); or (iv) severe (oxygen saturation <94% on air, ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) <300 mmHg, and respiratory rate above normal or lung infiltrates >50%).

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 for MacOS was used for statistical analysis. Regarding descriptive analysis, continuous variables were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR), and categorical variables as frequency and percentage. The t-student test was used for comparisons between continuous variables, while the Chi-squared test was used for comparisons between categorical variables.

The study’s research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of our center, and all data collected was kept confidential.

Results

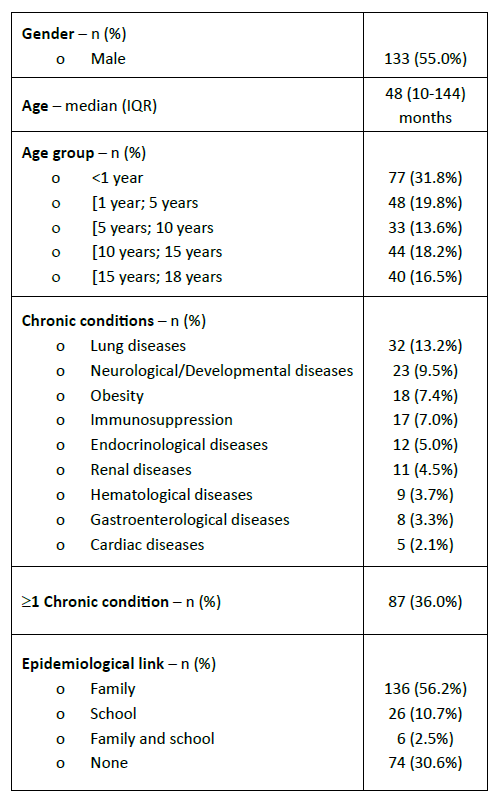

A total of 242 patients with higher male prevalence (n=133; 55.0%) were followed at our center. Infants represented almost one third of this population (n=77; 31.8%), and most were under the age of 10 years (Table 1). The median age at presentation was 48 months (=4 years; IQR 10-144 months).

Around one third of patients (n=87; 36.0%) had at least one chronic medical condition, the most frequent being lung disease (n=32; 13.2%), and 30 patients (12.4%) had more than one chronic condition (Table 1). Seventeen patients (7.0%) had immunosuppression before the development of COVID-19.

At the time of diagnosis, 136 patients (56.2%) had contacted a relative with prior COVID-19 infection, 26 (10.7%) reported a COVID-19 case in their school context, and 6 (2.5%) reported COVID-19 cases in either family or school context. For 74 children with COVID-19 (30.6%), there was no known epidemiological link with COVID-19 cases (Table 1).

The vast majority of this patient cohort (n=150; 62.0%) was diagnosed with COVID-19 in the ED, but also in regular appointments at the hospital (n=36; 14.9%), in pre-surgery screening (n=30; 12.4%), in other hospitals (n=24; 9.9%), and during the assessment of patients who were already hospitalized and developed further symptoms (n=2; 0.8%).

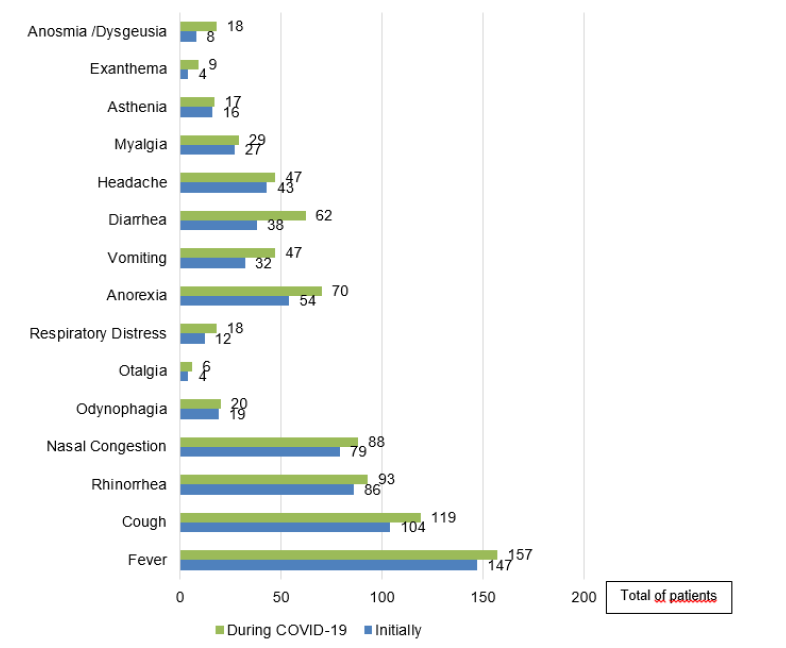

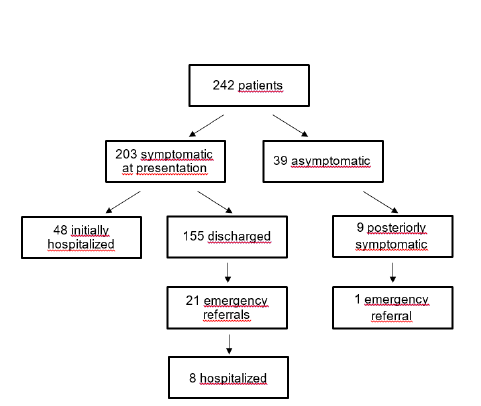

At diagnosis, 203 patients (83.9%) had at least one symptom and 39 (16.1%) were asymptomatic. Of these, nine (23.1%) subsequently developed symptoms. Among symptomatic patients (n=212; 87.6%), the most frequent complaints were fever (n=157; 74.1%), cough (n=119; 56.1%), rhinorrhea (n=93; 43.9%), and nasal congestion (n=88; 41.5%; Figure 1). The average number of days with symptoms before diagnosis was 1.6 1.8 days. Regarding symptoms that were not initially present but developed during the course of the disease, a relevant increase was observed in the incidence of diarrhea (3862), anorexia (5470), vomiting (3247), cough (104119), anosmia/dysgeusia (818), and fever (147157).

In the group of symptomatic patients, 48 were initially hospitalized (23.6%). Among the 194 patients who were discharged, 21 (10.8%) required medical re-observation, with eight of these (38.1%) requiring hospitalization (Figure 2). In the group of asymptomatic patients, only one (2.6%) required medical re-observation for symptoms subsequently developed, and none required hospitalization.

The main reasons for referral among the 21 patients who needed emergency assessment were gastrointestinal manifestations (abdominal pain, vomiting, or diarrhea; n=9; 42.9%), fever reemergence (n=7; 33.3%), and respiratory distress (n=5; 23.8%). These patients had a median age at presentation of 84 months (IQR 12-168), and 11 (52.4%) had chronic diseases.

Hospitalized patients had a median age of 12 months (IQR 2-144), and 26 (49.1%) were younger than 1 year old. The median days since disease onset until the decision for hospitalization was 3, with 18.9% of patients admitted after more than one week of symptoms. The percentage of these patients with chronic conditions was 35.8% (n=19). The main reasons for hospital admission was young age at presentation in 19 patients (35.8%), COVID-19 manifestations in 18 patients (34.0%), and prior chronic conditions in 10 patients (18.9%). Only three patients required rehospitalization, which was due to urinary tract infection, fever reemergence, and prolonged diarrhea. No significant differences were found between hospitalized (n=53; 21.9%) and non-hospitalized (n=189; 78.1%) children regarding age (p=0.123), sex (p=0.358), obesity (p=0.176), history of chronic diseases (p=0.323), respiratory diseases (p=0.644), or prior immunosuppression (p=0.305).

Most patients in this study sample (n=212; 87.6%) only required symptomatic therapy, and even among hospitalized patients, few required specific therapies, such as oxygen (n=10; 4.1%), non-invasive ventilation (n=2; 0.8%), high-flow nasal cannula (n=2; 0.8%), lopinavir/ritonavir and hydroxychloroquine (n=1; 0.4%), or remdesivir (n=1; 0.4%).

The median time of symptom duration in symptomatic patients was six days (IQR 4-10 days), with 112 patients (53.4%) experiencing symptoms for no more than one week.

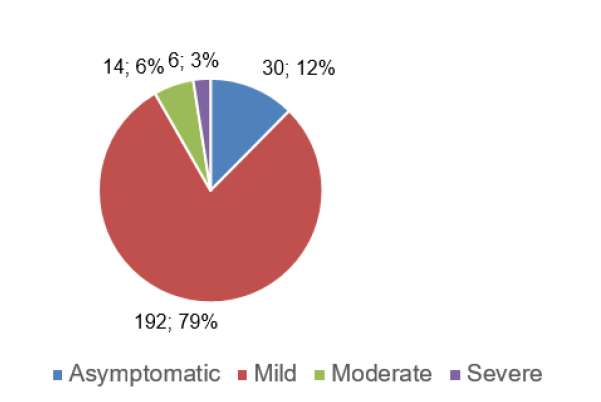

Regarding disease severity, the great majority of patients had mild disease or were asymptomatic through the entire course of the disease (91.7%), with only 14 (5.8%) patients fulfilling criteria for moderate disease and six (2.5%) for severe disease (Figure 3). When comparing children with asymptomatic or mild disease (n=222; 91.7%) with those with moderate or severe disease (n=20; 8.3%), no significant differences were found regarding age (p=0.847), sex (p=0.350), obesity (p=0.176), history of chronic diseases (p=0.287), respiratory disease (p=0.314), or prior immunosuppression (p=0.580). Only two patients required admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) due to respiratory distress in the context of pneumonia; one spent six days in the ICU and a total of 12 days in the hospital, and the other spent 12 days in the ICU and a total of 18 days in the hospital. One of these patients, a 14-year-old adolescent with a chronic degenerative disease, died after being admitted to the ICU with severe respiratory insufficiency.

Discussion

The understanding of the COVID-19 disease in children is still limited, with conflicting data reported in different studies. Regarding age, while the literature documents a growing incidence of the infection with increasing age,6 in the present study infants represented around one third of the sample (31.8%), with most (51.6%) being under the age of five years. This difference may be explained by the fact that they tend to go to the ED more often, on the one hand, and by the number of infants admitted to our hospital (49.1%), which is a referral center for pediatric hospitalization, on the other.

In this study, more than half (56.2%) of children with COVID-19 had previously contacted with an infected relative, which is in agreement with the literature reporting a low viral transmission in child care setting due to the social measures imposed by the lockdown.7) Around 16% of patients in this study had a positive SARS-CoV-2 test during screening, despite being asymptomatic at diagnosis. In the literature, this incidence varies substantially among hospitals, ranging between 0.6 and 1.3%.8 Moreover, a considerable number of children (30.6%) had no known epidemiological link (n=74), suggesting that this link should not be an isolated criterion for the decision to perform SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR testing. The sample included in this study had a high incidence of COVID-19, which may be related to its high incidence in the community.

In line with previous studies, fever and cough were the most frequent symptoms in this cohort.9) However, in view of the considerable number of patients that did not report fever during COVID-19 infection (25.9%), the strategy to perform SARS-CoV-2 testing based solely on this criterion is debatable and not recommended by the experts.4 On the other hand, and differently to the time of presentation, the most frequent symptoms arising since viral detection until disease resolution were gastrointestinal complaints, namely diarrhea, anorexia, and vomiting. Therefore, a high degree of suspicion and awareness should be kept for these symptoms, so as not to miss a potential diagnosis.

According to previous reports, COVID-19 appears to be less severe in children, with 15-42% presenting with mild disease and no symptoms.4,8,9 In agreement with this, 12% of patients in this cohort were asymptomatic and 79% had mild disease, with only 6% and 3% presenting with moderate and severe disease, respectively. A relevant proportion of patients (almost 20%) required hospitalization at diagnosis, which is a higher figure than the reported in recent studies, where hospitalization rates varied between 2.5 and 4.1%.10 The authors believe that this is due to the fact that this study hospital is a tertiary center, thus receiving children in need of hospitalization from other hospitals. Contrarily to other studies describing high rates of hospitalization in patients with chronic conditions (15-22% versus 2.5-4.1% in this study),11 in this study the percentage of patients with chronic diseases was similar in the overall patient population and in hospitalized patients. Additionally, pulmonary conditions, immunosuppression, or younger age at presentation, described elsewhere as risk factors for more severe disease, (10,12,13 were not identified in this study as contributors for more severe disease or hospitalization.

The burden that COVID-19 pandemic imposed on health systems prompted the development of new strategies to address and manage this new and unknown disease. Homecare surveillance enabled the follow-up of symptomatic patients and minimized unnecessary ED visits and hospitalizations. During follow-up, few patients required emergency referral, but a considerable number required hospitalization.

This study has some limitations that should be acknowledged, starting with its retrospective nature, which limited data collection and the information available for each patient. On the other hand, patient inclusion in the study was limited to September 2021, excluding the analysis of subsequently uncovered SARS-CoV-2 mutations. Lastly, the limited sample size, number of hospitalizations, and moderate/severe COVID-19 cases may have limited the conclusions.

Conclusion

COVID-19 presented as a mild disease in most children in this study, with non-specific and multiple symptoms. The close approach to these patients conducted at our center enabled a better understanding of this new disease and minimization of unnecessary visits to the Emergency Department and hospitalizations, while maintaining an adequate patient follow-up. Although most patients assessed in the study developed mild disease, some cases with moderate and severe presentation were also observed. No specific risk factors for disease severity were identified. Last but not the least, a homecare approach to pediatric COVID-19 patients showed to be a valid and safe option, even in patients with chronic conditions.