Introduction

Changing trajectories of media use in children and adolescents

Over the last two decades, the availability and use of digital media, including mobile devices and interactive and social media, has grown among children and adolescents and are now part of the daily activities of young children.1,2

A 2014 study found that in the United States, children younger than two-years spend about three hours a day watching screens. This represented more than double of the screen time (ST) consumption for the same population in 1997.3

In addition, a 2019 report from Common Sense Media found that 8- to 12-year-olds in the United States use screens for entertainment nearly five hours per day.4

In Portugal, a 2019 study by Cristina Ponte in children and adolescents aged 9 to 17 years reported an average screen use of 3,2 hours per day, with an increase to more than four hours in the oldest group.5

Also, the age at which children begin to regularly interact with media has shifted from four years to four months, meaning that children today are “digital natives”, born into an ever-changing digital ecosystem that is enhanced by digital media.6

Regarding the Portuguese population, another study from 2019 concluded that 81% of children up to 18 months of age had already been exposed to a screen and identified a very early age of first exposure, between four and six months.7

With this new reality the term ST has emerged and is defined as the daily time spent in front of any type of screen, namely television, mobile phones, tablets, computers or video games.

The screen use has been classified by the level of engagement as active and passive. Active screen use can include videogames, online learning and video chat with friends and family. Passive ST, in which children receive screen-based information without high levels of cognitive engagement, include watching television, videos or scrolling through social media apps.8

Although there are benefits of media use for children, including educational potential, concerns have also emerged about their overuse, especially in early age, during the crucial period of brain development.

Recommendations from pediatric societies and other associations limit ST to promote healthy development. World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines recommends no screen exposure in children under two-years of age, less than one hour in children aged 2-5 years and no more than two hours of sedentary recreational ST per day in older children.9 A Position statement from the Canadian Pediatric Society also recommends no ST for children under two-years, a limit of less than one hour per day for children two to five years, and two hours of ST for children and youth aged 5 to 17 years.8,10) The 2016 guidelines on ST of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) advise for no screens under the age of two-years and one hour per day of high-quality programming for children two to five-years, with parents watching as well, to help children understand what they are seeing, and help them apply what they learn to the world around them. For children older than six years, recommendation focus on placing consistent limits on the time spent and types of media used and not allowing that ST affects sleep, exercise and other activities.11

Backgroung

There is growing evidence associating COVID-19 pandemic- related lockdown and stay-at- home orders with a remarkable increased in ST in children and adolescents.

The authors present a review of the relevant and current scientific literature about ST in COVID-19 pandemic, and the repercussion of the pandemic on the use of digital media, the inherent risks, as well as its impact in different domains of physical, neurodevelopmental and mental health.

The MeSH terms used were “Screen time” “COVID-19”. Important and specific research describing ST in children and adolescents were also incorporated in this revision.

Main exto

COVID-19 pandemic - impact on screen time

AT March 2020, about three billion people worldwide were sheltered at home, and more than 130 countries have enacted restrictions to limit movement of their citizens hoping to prevent the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).12 This has resulted in a global lockdown and social distancing with incalculable adverse consequences for economic progress, governments, as well as for physical and mental health.13

It has been estimated that due to the global lockdown, 1.5 billion children stayed at home at the end of April 2020 (WHO, 2020).14) The nation-wide restrictions, particularly the closure of schools and child-care facilities and the stay-at-home orders have left children physically cut off from their schools, and daily schedules were severely disrupted. Also, the closure of parks, playgrounds and recreational facilities, reduced the possibilities for children to maintain an active and healthy lifestyle.

In this context, technology has become vital to participate on online educational classes, enable children to interact with each other and with their family, and to recreational and playing time.15

Children have been largely spared from the direct health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic but other long-term effects of pandemics are also concerning, like exacerbation of childhood obesity, ST exposure and increase of mental and neurodevelopmental health problems.16,17 In fact, among the many issues discussed in the realm of the pandemic, a growing number of scientists point towards the problem of digital technology overuse by children and adolescents.18,19

The first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with a dramatic increase in ST time for children of all ages, from very young ones to adolescents. To illustrate this problem scientific studies have been conducted worldwide.

A large European Study in which participated ten European countries, including Portugal, evaluated physical activity (PA) and screen time (ST) during COVID-19 pandemic. 8395 children were enrolled, aged 6-18 years (median age of 13 years), 53,1 % were girls and 57,6% were urban residents.20 This study showed that two months after WHO declared COVID-19 as a global pandemic 81% of children and adolescents did not meet the physical activity recommendation of at least 60 min of moderate to vigorous-intensity physical activity (MVPA) per day. Around 70% of participants exceeded the recommended 2h/day of total ST on weekdays in the whole sample, and just under two-thirds of participants exceeded the ST recommendation on weekends.

The findings were similar in both Canadian (Moore et al. 2020) and Chinese (Xiang et al.2020) surveys reported a much higher ST during the pandemic than before. The Canadian study of 1472 children (5-11 years) and youth (12-17 years) found that 81.2% were not meeting physical activity goals and 88,7% did not meet ST guidelines. The leisure ST was reported as much higher than before the COVID-19 outbreak (5.1 h/day and 6.3h/day, for children and youth respectively). Also the social media ST was much higher.21 The Chinese survey analysed data from 2426 children and adolescents. The median time spent in PA decreased drastically, from 540 min/week (before the pandemic) to 105 min/week (during the pandemic), yielding 435 min reduction on average. Total ST considerably increased (+1730 min [or approximately 30 h] per week on average)- ST during leisure was also prolonged, indicating that nearly a quarter of students engaged in long ST for leisure.22

In Portugal, the COVID-19 pandemic motivated the closure of daycare centers on 16th of March 2020 and lockdown measures between 18th of March and 2nd of May 2020, which inevitably changed family routines. These changes also had an impact on the children ST. A study by Pombo et al (2022) about the effects on household routines of children under 13 years old, involving a sample of 2159 children, found that ST had increased since the pandemic onset and that boys were more likely to engage in active ST; along the age groups, there was a trend for an increase of the overall sedentary time and an associated decrease of the overall PA time.23

Data from 12 countries focusing on a large cohort of toddlers and preschooolers (n=2209, aged 8 to 36 months) during COVID-19 lockdown reported that toddlers with no online schooling requirements were more exposed to ST during lockdown than before.24

A previous study from Chile (Aguilar-Farias et al. 2021), evolving 3157 children from 1 to 5-years (mean age 3,1 years), also found that, across all ages, mean time spent in physical activity decreased (3,6h/day to 2,82h/day) and recreational ST increased (1,66h/day to 3,05h/day). Although sleep duration increased 10.92h/night to 11,01h/night; p =0.001), sleep quality declined (5,68 to 4,93).25

In a 2021 study from Portugal with 520 children aged one to five years, the mean age of first exposure to screens was 13.9±8.0 months and most of the children were exposed to ≥1 screen daily. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, 74.0% and 78.5% of children had excessive ST during the week and the weekend, respectively; during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, these values increased to 95.2% and 92.7%.26

Available data from other studies also demonstrated decline in physical activity and remarkable increase in ST during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, and alert for the increased risk of obesity and myopia.21,27,28

Factors associated with screen time in children and adolescents

Studies have identified factors associated with excessive exposure to screens: child´s age, existence of siblings, socio-economic status, parent´s age, caregiver’s education, caregiver´s ST and behavior towards ST, household size and structure, number of screens and its location at home.20,24,29

Of note, these effects appear to vary across studies and countries, and robust relationships have been challenging to define.

ST during COVID-19 lockdown was negatively associated with socio-economic status and maternal educational level and positively associated with child age (with older children reported to have more ST than younger ones).20-21,24,26

The median age of first exposure to screens also showed a significant association with excessive ST.26,29

Caregiver ST and attitude towards ST was shown to influence children´s ST, with caregivers who reported having more ST themselves also reported their children had more ST.24) Furthermore, parental encouragement, support and engagement were also positively associated with healthy behaviors, including lower ST.21

Other factor contributing to increasing ST during COVID-19 pandemic was the disruption in childcare, particularly among under-resourced families. It has been challenging for parents, especially those who take care of children alone, to supervise their screen time, letting children entertain themselves as they need to engage in other household tasks and/or online work.30,31

Schedules are important for children as they engage in a greater number of unhealthy behaviors on less-structed days.32,33) Following a daily schedule/ routine increased the odds of meeting ST recommendations.20

Playing outdoors more than two h/day and being active in online platforms of physical education increased the odds of healthy levels of physical activity and ST and acted as a health factor promoter.21,22

Research shows that the level of cognitive engagement while using screens can modify risks associated with its prolonged use. In the COVID-19 pandemic there has been a reported shift to more passive ST.21) Passive use has been associated with a reduced ability for children to process verbal information and with increased anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescence.34

The identification of factors associated with excessive ST during COVID-19 pandemic is extremely important as could indicate possible areas for individual - parental and policy health interventions.

Screen Time and Health Outcomes - Benefits and risks

Media use harbors both risks and benefits to the health of children and teenagers.

Evidence-based benefits on the use of digital and social media were identified and include: exposure to new ideas, knowledge and information; raising awareness of current events and issues; educational and recreational activities; contacts with friends and relatives; access to valuable support networks (especially helpful for children with ongoing illnesses or disabilities); social inclusion promotion; enhancing wellness and promoting healthy behaviors on online platforms (e.g. smoking cessation, healthy nutrition and physical exercise).11,35,36

During COVID-19 pandemics the media technology allowed online classes and access to educational materials with important educational opportunities and benefits. In addition, social media and video chatting allowed children to be connected with their friends and family, while keeping social distancing. It also allowed for enabled the access to platforms of physical activity and recreational activities.37,38

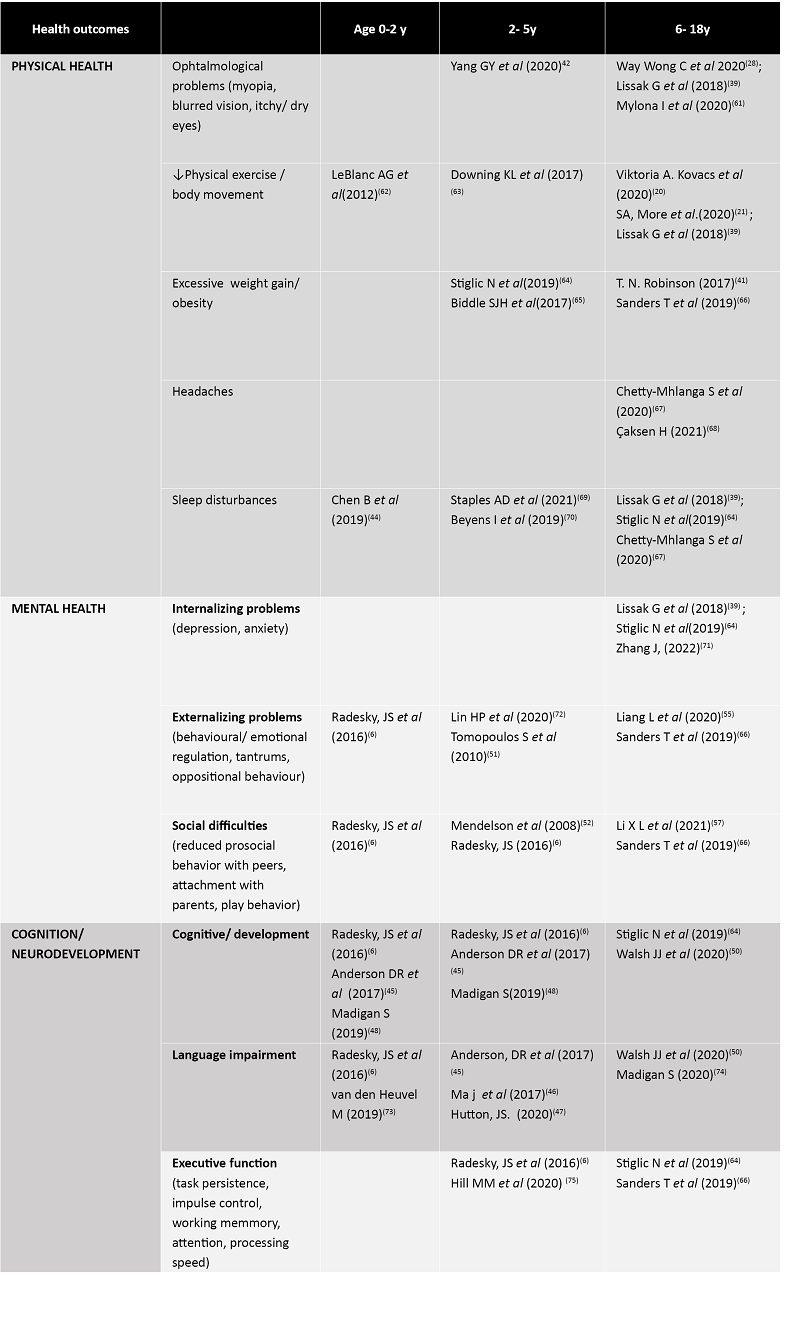

A growing body of evidence associates excessive and inadequate use of digital media with physical, psychological, social and neurodevelopmental adverse consequences.34,36)Table 1 shows the adverse effects attributed to increased screen use by children and adolescents across age categories.

Additionally, it seems that there is a dose-response relationship, as the time of exposure increases, the greater is its functional impact.29,39

Excessive ST has been associated with physical health effects such as obesity and metabolic syndrome, myopia and ophthalmological problems as well as with headaches.28,39,41,42

Sleep disturbances are also common and the mechanism underlying this association include arousing content and suppression of endogenous melatonin by blue light emitted from screens.36,43-44

Population-based studies suggested a negative association between excessive ST in early childhood and poor language development and literacy.6,45,46 One recent study found an association between increased screen-based media use and lower microstructural integrity of brain white matter tracts supporting language and emergent literacy skills in pre-school-aged children.47 On the other hand, another study found that while increased ST was associated with lower language skills, quality screen time (educational programs) and caregivers co-viewing and supporting during ST was associated with stronger language skills.48

Other neurodevelopmental implications include impaired executive function, such as task persistence, impulse control, attention, working memory and general cognition.6,39,46,49,50

It is important to state that children younger than two years need hands-on exploration and social interaction with their caregivers in order to develop their cognitive, language, motor and social-emotional skills. Because of their immaturity, infants and toddlers cannot learn new information from digital media as they have difficulties in transferring knowledge from screen to their three-dimensional life. They need their parents and caregivers to watch it with them: co-viewing, and reteaching the content in real life parent- child interaction.6,11

Regarding social-emotional development in youth, play is crucial because provides enriched experiences between parents and child, building social reciprocity.6 Media use is associated to decreased parent-child engagement, including playing and reading together.51,52

Young people can be particularly vulnerable to the harms associated with excessive screen time or gaming including exposure to inappropriate, erroneous information, harmful content (violent or sexual) and unsafe content and contacts. During the pandemic concerns about increases in online child abuses and cyberbullying also emerged.35,37

Excessive ST can also result in online gaming and addictive behavior leading to development of gaming disorder. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined Internet Gaming Disorder criteria in the International Code Disorders - ICD-11.53

Furthermore, media screen time use in children has been associated with adverse mental health outcomes and impaired social communication skills.39

This impact has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic as reported in several studies. A recent study in USA showed that nearly 45% of youths reported a negative impact on mental health.54 Another study from China suggested that 40.4% of the sampled youth were suffering from psychological problems.55

Studies have shown an association between high prevalence of mental health problems, namely anxiety and depression, and prolonged exposure to social networks, both in children and in adults.56

A longitudinal study of Ontario children examined different types of screen time (television, computer, video games, electronic learning) and mental health. In younger children (mean age 5.9 years) higher television or digital media time was associated with higher levels of behavioral problems and hyperactivity/inattention. In older children and youth (mean age 11.3 years) they were associated with higher levels of depression, anxiety, and inattention.57

Research tells us that the implications of COVID-19 on the mental health of children and young people will presumably be prolonged in time and long- term follow-up is needed to help children and identify intervention needs even after the pandemic.58

Further multi-level studies on different aspects of ST are warranted.

Recommendations for parents/ caregivers to promote healthy screen use

“Screen hygiene” is important to encourage healthy screen habits, in order to diminish the adverse effects of screen use and underpin its benefits.

Educators and doctors/ pediatricians play a vital role in helping parents to identify good and high- quality content and to find strategies to monitor, co-view, limit, and reinforce what is learned from ST.6,29,35,36)

It is important to set rules about content, time limits and where children can use media. Parents should establish sufficient screen free periods each day and ensure that children get the recommended time of duration of sleep and, more important, better quality of sleep.35,36,59,60 Regarding physical activity, parents and caregivers should encourage children to integrate at least two hour of outdoor safe activities into daily routines.9,10

Based on studies, setting structured daily programs by following the usual school schedule and organizing the remaining daily time might be a promising intervention strategy to increase physical activity and limit sedentary recreational ST.20,29

Most importantly, because parent media use is a strong predictor of child media habits, parents must act as role models for digital media healthy habits. Advice on achieving this goal may include enhancing child- parent interactions, preserving time for learning, physical, social and emotional experiences.35,36

There are digital tools that can help parents and caregivers and support implementation of consistent rules about media use, monitoring and setting limits to ST, like the Family Media Use Plan (www.healthyclindren,org/MediaUsePlan) and Family Link (https://families.google.com/familylink/ ).36

There are evidence-based strategies to promote healthy screen habits for children and their families which offer an approach to encourage healthier screen use in the home setting and mitigate potential harms. Overall evidence- based recommendations for promotion of healthy screen hygiene are listed in table 2.

Table 2 Recommendations about healthy screen use for parents and families

Adapted from Toombs E et al. Science Briefs of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. 2022 29

Policy interventions to promote healthy screen use

The rise in ST during the pandemic is a public health concern and policy-level interventions are also necessary to support parents, caregivers and children to reduce ST. Policies which promote accessible outdoor facilities and green spaces for recreational and physical activities, offer active and social alternatives to screens, contribute to healthy child and youth development. These could include, for example, avoiding closure of schools and recreation ensuring open access to in-person school and related extracurricular activities for children of all ages, as well as access to community recreation.29

In the context of COVID-19 pandemic it is also crucial to ensure that there are appropriated resources in school and community to overcome any developmental delays (particularly in the preschoolers and school-aged children) and mental health advisers, particularly for adolescents.60

Investments must also be done in health education programs to teach children and youth to use media technology in a conscious, safe and healthy way.

Conclusion

Scientific evidence associates COVID-19 pandemic-related restrictions with increased ST in children and adolescents.

Prolonged and inadequate use of media can affect physical, cognitive and mental health outcomes.

More research is required, including randomized-controlled- trials, to further understand the impact of ST increase during COVID-19 on health outcomes and potential relationships with types of screens, level of engagement, direct and long-term effects and influences of parental monitoring, among others.

Research tells us that the implications of COVID-19 in children's health will presumably be prolonged in time and long- term follow-up is needed.

Interventions are needed to mitigate this effect and prevent this increase in ST to become the new normal.

It is important to inform parents and caregivers about the importance of controlling their child´s ST and content and give them evidence- based recommendations to encourage healthy digital media use.

In addition, policies are needed to ensure alternatives to ST, promoting socialization and physical activity, and health educational programs about media use should be implemented.