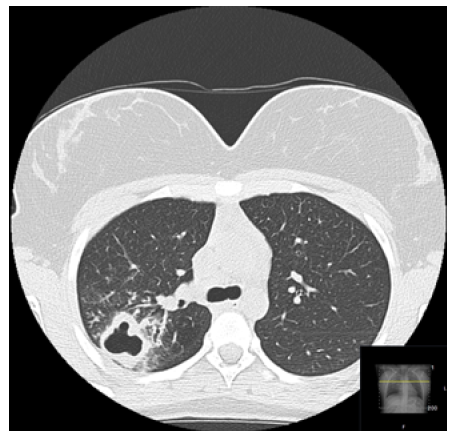

A 15-year-old female was observed at the Pediatric Emergency Department due to an episode of hemoptoic cough during physical activity and fever with 24 hours of evolution. She also reported myalgia, asthenia, dry cough, and thoracalgia for three days. No weight loss, night sweats, skin lesions, or adenomegaly were referred. On physical examination, scattered wheezing was detected on pulmonary auscultation. The patient tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 infection in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. Plain chest radiograph documented cavitation in the right upper lobe and interstitial infiltrate in the lower third of the lungs (Figure 1), and chest CT scan confirmed the cavitation with 30 mm in diameter (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Chest CT scan showing the posterior segment of the upper lobe of the right lung with central cavitation with 30mm of diameter, with a thick and slightly anfractuous wall

What is your diagnosis?

The patient was hospitalized in the Pediatric Department for surveillance and treatment. A more detailed study was performed, showing acid-fast bacillus (Ziehl-Neelsen) on sputum microscopy, positive PCR and culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, positive Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA), and negative anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), as well as anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) and anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies were negative. Notification was carried out through the National Surveillance System (SINAVE).

Treatment consisting of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol was instituted, and apyrexia was achieved on the fifth day of hospitalization. Four episodes of hemoptoic cough, in moderate amount, without hemodynamic instability were ascertained, during hospitalization.

Significant clinical improvement was observed, and the girl was discharged on day 12 with referral to the attending physician and to a Pneumology Diagnosis Center. Contacts were tracked, including teachers, classmates, and cohabitants. Only the patient's younger sister had positive IGRA, performing chemoprophylaxis for latent tuberculosis (TB) infection.

Discussion

TB is an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis that can be multisystemic, but mainly affects the pulmonary system.1,2 Being a slowly progressive disease, symptoms are usually discrete in the beginning and become more conspicuous with time and according to the site of manifestation. In pulmonary tuberculosis, initial symptoms usually consist of cough with production of scanty sputum and hemoptysis, evolving to dyspnea and chest pain as the disease progresses.1,2

In the assessment of adolescents with suspected tuberculosis, the workup usually consists of a combination of history and physical examination and radiological and microbiological tests (smear microscopy, mycobacterial culture, and/or PCR testing).2 Most adolescents present with intrathoracic tuberculosis, defined as parenchymal lung disease (infiltrates, cavities, miliary disease), pleural effusion, or intra-thoracic (hilar, mediastinal) lymphadenopathy.2

The recommended drug therapy for tuberculosis in adolescents is the same as in children and adults and consists of a combination of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol.2

Many adolescents with pulmonary disease are able to transmit the condition in large scale due to the high number of social contacts, so investigating their contacts is a priority.2

Early diagnosis and intervention are crucial for favorable outcomes.3,4 In this clinical case, the presence of cavitation supports a delay in diagnosis, possibly related to the COVID-19 pandemic context, which delayed patients’ arrival at health institutions. Improvements in the prevention and diagnosis of the condition are necessary.4