Introduction

Anaphylaxis is a potentially fatal systemic hypersensitivity reaction with rapid onset of signs and symptoms following exposure to an allergen. (1 Its exact incidence and prevalence are hampered by underdiagnosis and underreporting.2 This is due to the variability of presentations and definitions of the condition, as well as the non-specificity of disease coding systems and the lack of data and specific laboratory tests that allow a rapid, reproducible, and unequivocal diagnosis. In addition, the onset of anaphylactic episodes is acute and unpredictable and may resolve spontaneously, leading to underdiagnosis and thus underreporting. The prevalence of anaphylaxis in children is increasing, currently ranging from 0.04% to 1.8%.3,4 In the age group under four years, the incidence of anaphylaxis is three times higher than in other groups.2,5

Food is the most common cause of anaphylaxis in children, followed by drugs and hymenoptera sting.1,3-5 In a Portuguese study conducted over 10 years, the main culprits were cow's milk (32%), tree nuts (16%), shellfish (13%), eggs (12%), and others.6 The type of food involved varies according to geographic area and local diet.1,6-8 Drug-induced anaphylaxis has been mostly related to antibiotics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).6,9 However, this type of reaction is more common in adults than in children.6,9

In children, asthma, laryngitis, bronchiolitis, and mastocytosis with skin involvement greater than 90% increase the risk of severe anaphylaxis.10 The presence of fever, upper respiratory tract infection, exercise, and emotional stress stand out as common cofactors involved in anaphylactic reactions.10

The diagnosis of anaphylaxis is a clinical one. Clinical criteria have been proposed by various organizations, including the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) and the World Allergy Organization (WAO).1,11 Signs and symptoms from various organ systems may be present, including the skin (with pruritus, urticaria, erythema, angioedema), gastrointestinal system (with abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea), upper and lower respiratory system (with rhinitis, hoarseness, laryngeal edema, stridor, dyspnea, cough, wheezing), and cardiovascular system (with dizziness, hypotension, syncope, shock). The diagnosis of anaphylaxis is more challenging in younger children due to their difficulty in describing certain symptoms. In these cases, signs such as irritability and behavioral changes may be present.1 Laboratory tests are available to support the diagnosis, but they are not specific for anaphylaxis and have low sensitivity. Some of these tests include measuring levels of mast cell mediators such as tryptase, histamine, and platelet-activating factor, which may be elevated in these reactions.10

The first-line treatment for anaphylaxis is intramuscular epinephrine administration at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg, which can be repeated after five minutes.1,11 There are no absolute contraindications to its administration. After administration, patients may experience anxiety, palpitations, dizziness, headache, and skin pallor. If the reaction and epinephrine administration occur outside the hospital, the patient should be immediately taken to the hospital for clinical evaluation. Second-line treatment includes removal of the trigger if possible, correct positioning of the patient, and administration of high-flow oxygen, intravenous fluids, short-acting bronchodilators, antihistamines, and glucocorticoids.

Several studies have reported the underuse of epinephrine in children, with the most common reasons being the caregiver's inability to recognize the severity of the reaction, fear of injection, waiting for other symptoms to develop, uncertainty about whether epinephrine would be needed, or unavailability of an autoinjector.12

Patients with respiratory compromise should be observed for six to eight hours. If hypotension is present, observation should be extended from twelve to twenty-four hours.1,13

Discharge should include advice on allergen avoidance (if identifiable and possible), a prescription for an epinephrine autoinjector (EAI), education on how and when to use the EAI, and referral for outpatient consultation with an allergy specialist.1,11

Goals

The aim of this study was to analyze the episodes of anaphylaxis in children admitted to the Pediatric Emergency Department (ED) of a central hospital between 2012 and 2021, and to perform a detailed characterization of this population and the etiopathogenesis, clinical features, and therapeutics of anaphylactic reactions.

Material and methods

This was a retrospective study based on the clinical records of children/adolescents admitted to the Pediatric ED of a central hospital for anaphylaxis. Anaphylaxis episodes were characterized according to the 2014 EAACI guidelines.1

The following ALERT and ICD9 diagnostic codes were screened for patient selection: (995.0), (995.0), (995.6), (995.60); (995.61); (995.62); (995.63); (995.64); (995.65); (995.66); (995.67); (995.68); (995.69); (V14); (V15.06); (V14.0); (995.3); (V14.0); (V14.2);(V15.06); (V14); (V14.1); (V14.4); (V14.5); (V14.6); (V14.7); (V15.02); (V15.05); (V15.08); (V15.01); (V15.03); (V15.04); (V15.07); (525.66); (V14.3); (V14.9); (V15.09).

All cases that did not meet the diagnostic criteria for anaphylaxis according to the 2014 EAACI guidelines were excluded.

Data were anonymized and subsequently stored and processed in Microsoft Excel 2019 and SPSS Statistics 28. Categorical variables were presented as absolute and relative frequencies, and continuous variables that were not normally distributed were presented as medians and ranges.

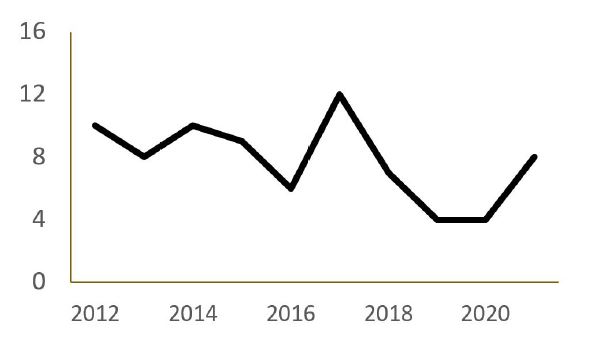

Figure 1 Number of anaphylaxis episodes of per year in the Pediatric Emergency Department of the study hospital

This study was approved by the Health Ethics Committee of Centro Hospitalar de Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho, EPE.

Results

A total of 78 anaphylaxis episodes were recorded in 57 children and adolescents between 2012 and 2021. Most patients were male (n=49; 62.8% vs. n=29; 37.2% of females) and the median age was 9.5 years (range 0.5-17 years). In 7.7% of cases, children were one year old or younger.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of anaphylaxis episodes per year. The highest number of anaphylaxis admissions to the Pediatric ED (n=12;15.4%) was recorded in 2017, and the lowest number of admissions (n=4; 5.4%) was recorded in 2020.

At least one previous episode of anaphylaxis was identified in 5.7% (n=10) of patients.

Anaphylactic reactions occurred more frequently at home (n=53; 67.9%), followed by school (n=10; 12.8%).

Asthma was recorded in 29.8% (n=17) of patients and allergic rhinitis in 21.1% (n=12).

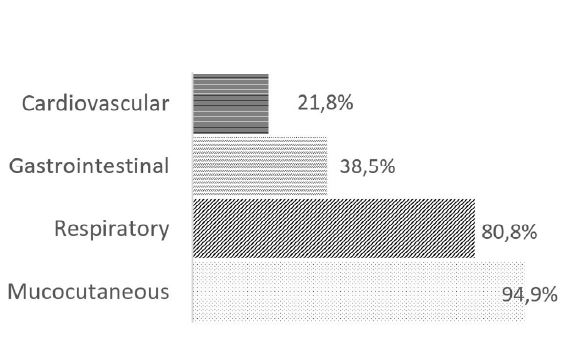

Mucocutaneous manifestations were seen in 94.9% (n=74) of the episodes, followed by respiratory manifestations in 80.8% (n=63), gastrointestinal manifestations in 38.5% (n=30), and cardiovascular manifestations in 21.8% (n=17; Figure 2).

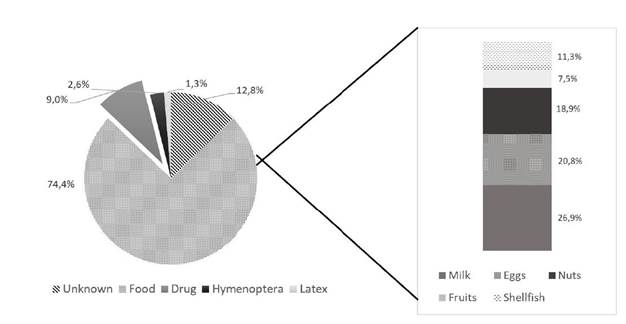

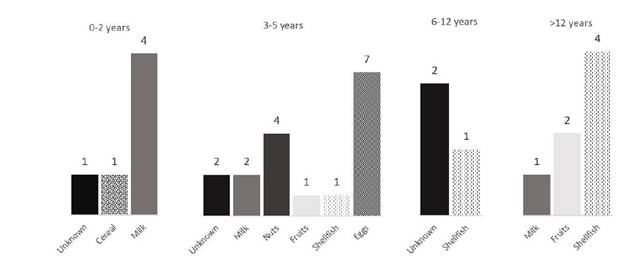

Trigger foods were identified in 74.4% (n=58) of cases. The most common trigger food was milk in 26.9% of cases (n=16), followed by eggs in 20.8% (n=11; Figure 3). Drug reactions were identified in 9% (n=7) of cases, and the main culprits were NSAIDs (42.9%) and antibiotics (28.6%). No etiologic agent was identified in 12.8% (n=10) of cases. Figure 4 shows the causes of food anaphylaxis categorized by age at first reaction, with milk and eggs standing out in the youngest children and shellfish in the oldest children.

EAI was used by 52.9% (n=18) of patients who already had the device. In the ED, epinephrine was administered in 65.4% (n=51) of cases, with prevalence of the intramuscular (n=42; 82.4%) over the subcutaneous (n=9; 17.6%) form. In the 44 first episodes, epinephrine was administered in 79.5% (n=35) of cases. In the 34 recurrent episodes, epinephrine was administered in 88.2% (n=30) of cases. Epinephrine was used alone in 2.6% (n=2) of cases. Systemic corticosteroids and antihistamines were used in 94.9% (n=74) of cases each. Bronchodilators were used in 34.6% (n=27), oxygen therapy in 10.3% (n=8), and fluid therapy in 30.8% (n=24) of cases. Only in one episode were all pharmacological classes used.

The median observation time in the ED was 13 hours (range 2-26 hours). No patient required intensive care.

At discharge, 67.9% (n=53) of children were referred to an outpatient consultation. Of note, some patients were already being followed at this consultation and may not have been included in this referral.

Overall, 95.5% (n=42) of first episodes were referred to an outpatient allergy consultation, and an EAI was prescribed in 84.1% (n=37) of cases.

Discussion

The present study found that hospitals’ diagnostic coding systems do not include the diagnosis of anaphylaxis, but only some subtypes of “anaphylactic shock” and questionable classifications such as “hypersensitivity diseases”, leading to diagnostic inaccuracy. This makes it difficult to estimate the true incidence and prevalence of the condition.

There was a decrease in the frequency of anaphylaxis episodes in 2020, with only four episodes identified. This may be related to the COVID-19 pandemic, as children were confined to their homes and less exposed to triggers, and ED visits decreased significantly during this period.14 In a study of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s health in Portugal, a significant proportion of parents reported that they would have gone to the ED earlier, more often, or instead of other medical services for their children’s symptoms if there had been no pandemic.14

Milk and eggs are the most common food triggers of anaphylaxis in infants born in Portugal, where the Mediterranean diet is common, as confirmed by the results of the present study.8,15,16 This study also showed that food etiology prevailed over other etiologies, followed by drug etiology, in agreement with previous studies carried out in Portugal.6,7,17 In younger children, foods such as milk and eggs predominate, while in older children, shellfish and fruits predominate, which is in line with the results of other Portuguese studies.6,7 The difference between younger and older children is due to dietary diversification and the inclusion of more foods in the diet as children grow.8,16

In this study, there was a significant proportion of patients with asthma, which is of concern as it is associated with an increased risk of severe anaphylaxis.10

Clinically, mucocutaneous and respiratory manifestations stood out in this cohort, in contrast to cardiovascular manifestations reported in the literature as more common in adolescents and adults.10 The rate of cardiovascular symptoms was similar to the results reported in other Portuguese studies.6,7 Although mucocutaneous manifestations are very common in children, their absence in four cases in this study does not exclude anaphylaxis. Respiratory symptoms are also common and are often associated with the presence of asthma.18) In this study, 89.2% of the cases corresponding to children with a previous diagnosis of asthma presented with respiratory symptoms, confirming what is described in the literature.18,19

Epinephrine is the first-line treatment for anaphylaxis and was used in most episodes in this study, which is positive given its underuse reported in other studies.7,20 This high rate of epinephrine prescription is also positive because non-prescription is associated with an increased risk of mortality.1) Still, only about half of the patients who had the EAI in this study actually used it.

Nine anaphylaxis episodes in this study were monitored for 24 hours or more, most of which were characterized by cardiovascular symptoms such as hypotension. Early discharge and therapeutic noncompliance increase the risk of recurrence due to biphasic anaphylaxis, increased severity, and death.13

The criteria for epinephrine prescription are controversial. Some authors argue that EAI should be prescribed in cases of anaphylaxis to food, latex, aeroallergens, and other potentially unavoidable allergens, as well as in cases of exercise-induced anaphylaxis , coexistence of poorly controlled asthma and food allergy, idiopathic anaphylaxis, anaphylaxis to hymenoptera, and in children with severe skin reactions or mast cell changes.1

National and international guidelines recommend referral to a specialist in allergic pathology for further evaluation, education, EAI prescription (if not already prescribed), and development of preventive strategies.1,11 In this study, more than half of children were referred for outpatient allergy consultation, including almost all cases of first anaphylaxis episodes.

Conclusion

Anaphylaxis has a wide spectrum of severity: some reactions may resolve spontaneously, while others may be fatal.

Although the incidence of anaphylaxis is low, it is part of everyday life in pediatric wards and EDs. Training of healthcare professionals in the diagnosis and management of this type of reaction is essential. It is necessary to develop action protocols with rapid and assertive approaches to the problem.

In this study of pediatric patients, food was the most common anaphylaxis trigger. This confirms that there is still a lot of work to be done in this field, such as educating parents and children to identify allergens and choose alternative foods.

Patient and family awareness of the seriousness of this condition is critical to its early recognition and management. Knowing the indications and how to administer the EAI can save patients’ lives.

AUTHORSHIP

Cristina Coelho - Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Visualization; Writing - original draft

Liliana Patrícia Pereira - Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology

Cátia Santa - Conceptualization; Methodology

Cláudia Pedrosa - Supervision; Writing - review & editing