Introduction

Several gastroesophageal diseases have been associated with psychiatric conditions.1) Notably, psychiatric comorbidities are observed in more than one in seven children diagnosed with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), an immune-mediated disease of the esophagus characterized by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and eosinophil-predominant inflammation (≥15 eosinophils per high-power field) on biopsy.2) While EoE often presents with gastroesophageal symptoms, children may also present with extraintestinal manifestations and behavioral issues. In addition, the chronic nature of the disease, combined with long-term treatment regimens and strict follow-up protocols, can significantly impact the quality of life of patients and their families.3) In fact, children with EoE have been found to experience higher rates of anxiety symptoms compared to healthy counterparts, and evidence suggests that these patients face increased emotional and behavioral challenges and poorer adjustment strategies as they grow older, with anxiety symptoms worsening with age, underscoring the need for developmental considerations in the management of these cases.4) Studies in the pediatric population report that 15.5% of children and adolescents with EoE exhibit symptoms of anxiety and depression, with 19% of older patients (11-17 years) reporting these symptoms compared to 9.3% of younger patients.5) Of note, when not stratified by age, the overall prevalence of anxiety in children with EoE has been reported to be as high as 41%.4)

The most commonly identified symptoms include excessive worry about the disease, physical symptoms of anxiety such as autonomic arousal, and school avoidance.6,7) Anxiety symptoms are often linked to concerns about food reactions, dietary choices, and the stress associated with medical procedures such as upper endoscopies.8,9) Interestingly, a patient’s perception and emotional response to EoE symptoms − such as how much attention they pay to the symptoms and how distressing they find them − may play a more significant role in explaining symptom severity than objective medical findings.10) Two related cognitive-affective processes − esophageal hypervigilance and symptom-specific anxiety − are emerging as critical factors in understanding patient-reported outcomes across esophageal diseases. Hypervigilance, or the tendency to overly focus attention on physical sensations in the esophagus, and anxiety related to the presence or possibility of symptoms may better characterize dysphagia symptoms than the physiological data typically used to assess esophageal conditions.11,12

Herein is reported the case of a 12-year-old male adolescent with anxiety and somatic symptoms since the diagnosis of EoE. The case highlights the cognitive, behavioral, familial, and psychosocial challenges that children and adolescents with EoE may face and contributes to the growing understanding of the broader impact of this condition.

Case report

A 12-year-old male was referred to the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Liaison consultation for anxiety symptoms related to a recent diagnosis of EoE. His medical history was notable for asthma, which had been controlled for the past two years without significant episodes.

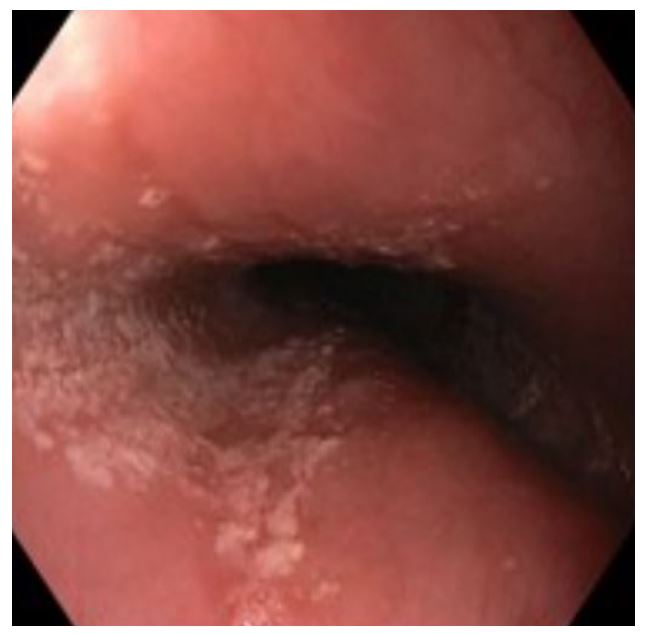

The patient reported a physical sensation of a lump in the oropharynx during meals and a persistent fear of choking on solid foods. Approximately one month prior to the diagnosis of EoE, which was confirmed by the Gastroenterology team three months before the consultation, the patient experienced dysphagia and episodes of food impaction when attempting to eat solid foods. There was no history of nausea, vomiting, or other gastrointestinal symptoms. In addition, the patient had no constitutional symptoms such as weight loss, fever, or other signs of systemic disease. The diagnosis of EoE was confirmed by upper endoscopy and biopsy, which revealed longitudinal striations and concentric rings along the esophagus and a dense eosinophilic infiltrate (60 eosinophils per high-power field), respectively (Figures 1 and 2).

The patient was prescribed a proton pump inhibitor (lansoprazole, 30 mg/day) and an inhaled corticosteroid (fluticasone, 125 mcg/day). Despite a thorough evaluation that ruled out alternative organic etiologies and appropriate treatment of EoE with topical corticosteroids, the patient continued to experience a persistent pharyngeal sensation of occlusion ("like a ball in the throat") and a foreign body sensation when attempting to eat. These symptoms were accompanied by an increasing fear of swallowing solid foods, resulting in a diet restricted to liquids. This fear extended to all previously preferred foods and all contexts of daily life, taking on the characteristics of a phobia. Symptoms were particularly aggravated on days preceding follow-up visits or endoscopic re-evaluations for EoE, highlighting their psychosomatic nature.

During the initial assessment, significant avoidance was observed, particularly in social settings involving meals. The patient demonstrated a refusal to participate in mealtimes at school or with friends due to fear of not receiving adequate assistance in the event of swallowing difficulties. Since being diagnosed with EoE, he exhibited intense concern and anxiety about his health. This was characterized by persistent thoughts about the severity of his condition, accompanied by recurrent upper gastrointestinal symptoms and heightened physical awareness of these sensations.

The patient showed an inhibited temperamental profile and was entering 7th grade, reporting few but long-lasting friendships. In particular, a fusional relationship with his mother was observed, characterized by significant dependence on her during meals and bedtime, suggesting a marked psycho-affective immaturity relative to his developmental stage. The family consisted of a nuclear unit, including both parents and the patient. The mother exhibited personality traits indicative of neuroticism, over-involvement, and an intense focus on food-related issues. She frequently emphasized that the patient had been a "difficult child" in terms of food acceptance since early childhood. In addition, the mother described the family dynamic as globally anxious and hypervigilant. Despite these observations, there was no documented history of formal psychiatric diagnoses within the family. The family belonged to a low socioeconomic class, with the mother working as a maid as the sole source of income. The father was retired due to a history of prostate cancer.

On mental status examination, the patient showed a passive and highly suggestible demeanor with an apparent age that seemed younger than his chronological age. Cognitive and behavioral features of anxiety were prominent, including an increased focus on somatic symptoms and a tendency to misattribute normal upper gastrointestinal sensations to physical illness. These misinterpretations were accompanied by catastrophic thoughts about the act of swallowing. Emotionally, the patient exhibited negative affectivity characterized by a limited range of positive emotional expressions.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR), the patient’s symptoms met the criteria for a diagnosis of somatic symptom disorder. He presented with distressing somatic symptoms, including globus pharyngeus and dysphagia, accompanied by maladaptive thoughts centered on the eating process. These symptoms were exacerbated by an avoidant behavioral pattern in response to distress. The excessive time spent thinking about these symptoms and the significant functional impairment caused by his condition led to his symptom severity being classified as severe at the initial assessment.

Given the pervasiveness of symptoms and their significant functional impact, pharmacologic treatment was initiated with sertraline oral solution, starting at 12.5 mg/day for seven days, followed by 25 mg/day until the next evaluation. At the same time, cognitive-behavioral strategies were implemented to encourage increased oral intake and greater autonomy from his mother. Improvement was observed four weeks after starting sertraline, with the patient able to swallow solid foods without behavioral distress. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry follow-up was conducted monthly. However, at the next evaluation, the boy’s speech remained focused on food and related anxiety. To optimize response, the sertraline dose was increased to 37.5 mg/day. Over the next three weeks, the patient’s anxiety decreased significantly and he expressed comfort eating a variety of foods.

Four months after the initial Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Liaison consultation, significant clinical improvement in the patient’s anxiety symptoms was observed. He demonstrated more spontaneous speech and effective coping mechanisms, even in the presence of significant stressors. Progress in autonomy and peer integration was also evident. Follow-up upper endoscopy revealed no significant lesions or features indicative of EoE, reflecting a favorable response to treatment.

Discussion

The literature indicated that the unpleasant symptoms of EoE have a significant impact on psychosocial aspects of life. While the clinical and histologic features of EoE have been extensively studied, there has been limited systematic evaluation of its psychosocial dimensions. These include depression, anxiety, somatization, conduct problems, self-esteem, and emotional, behavioral, and social adjustment.4) Because feeding skills are developed in infancy and continue to develop throughout childhood, any disruption in this process-whether due to discomfort or inflammation-can lead to long-term maladaptive feeding behaviors, potentially altering the child’s overall quality of life.13

Only a limited number of reports have explored the spectrum of feeding dysfunctions associated with EoE in adolescence. Despite his age, this patient exhibited significant functional impairment characterized by a pronounced dependence on his mother. Social disruption was evident, as his dysphagia had led to a pervasive fear and anxiety about eating in social settings.

This case highlights the critical importance of recognizing feeding dysfunction and food avoidance as cardinal symptoms of anxiety, which emerged immediately after the diagnosis of EoE. The patient also reported a sensation of an oropharyngeal mass that occurred exclusively at mealtimes, despite thorough evaluations that ruled out organic causes. This symptom is consistent with the psychological construct of the hysterical globus, also known as globus pharyngeus or globus sensation, and highlights the role of stress and psychological factors in its manifestation.14

Children and adolescents with globus sensation often exhibit traits such as neuroticism, introversion, and symptoms of anxiety and depression.15) For this patient, the pharyngeal sensation of a “lump in the throat” was a distressing experience, driven by an interpretation of physical symptoms as threatening and harmful, leading him to assume the worst about his health.

It should be noted that a somatic symptom disorder can coexist with an underlying medical condition. In this case, the patient exhibited anxiety-like traits accompanied by emotional and behavioral responses to the diagnosis of EoE. His distress was disproportionate to the actual severity of the disease, suggesting heightened psychological reactivity.

The persistence of somatizing symptoms in children may be influenced by individual characteristics such as hypersensitivity and anxiety, as well as difficulties in adapting to everyday challenges due to these emotional and temperamental factors. This highlights the need for a holistic management approach that addresses both the physical and psychological dimensions of such conditions.16) In this case, the somatic symptoms presented were highly distressing and significantly disrupted the patient’s daily life. The symptoms, localized in the throat, reflected a hyperfocus on a trivial physical sensation that occurred during eating. Although there was no evidence of serious organic disease, this sensation caused considerable discomfort.

A combination of cognitive-behavioral techniques − including psychoeducation, anxiety exposure, and feeding therapy − proved effective in reducing anxiety and improving the patient’s eating behavior. In addition, appropriate administration and dose optimization of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), specifically sertraline, reduced anxiety symptoms and allowed for more effective psychotherapeutic progress. Notably, research highlights a higher prevalence of psychotropic medication use among children and adolescents with EoE, even in the absence of formal psychiatric diagnoses, compared to their healthy peers. More than 1 in 7 children with EoE receive a psychiatric diagnosis, and similar proportions are prescribed psychiatric medications, underscoring the psychological distress prevalent in this population.2

This case highlights the need for a multidimensional approach to the management of somatic symptoms, even in the presence of organic disease. It also highlights the potential value of enhanced child and adolescent psychiatry liaison interventions for early identification and management of anxiety and somatic symptoms in patients with gastroesophageal disease.