Introduction

The rapid evolution of communication technologies has enabled children and young people to access social media, the internet, and smartphones at an early age. The use of these technologies to vent frustrations and aggressions has led to the emergence of the term cyberbullying,1 which is defined as a type of intentional and repeated aggression occurring in an electronic or digital context.2 Although bullying and cyberbullying are related, it is known that cyberbullying on its own has a significant emotional impact on children, sometimes surpassing the effects of traditional bullying.3 The potential anonymity of the perpetrator, the large audience reach, the difficulty in disconnecting from the social world, and the lack of face-to-face contact, all characterise cyberbullying.4

Cyberbullying has thus become a phenomenon of increasing importance globally, occurring across different age groups.5 The most common forms of cyberbullying are manifested through mobile phones (calls, text messages, videos, or images) and the internet (emails, chat rooms, messages, websites, social media, etc.). It is estimated that 95% of American teenagers use the internet, and of these, 81% have social media accounts.4

Hashemi differentiates cyberbullying from traditional bullying, suggesting that cyberbullies can intimidate a large number of victims simultaneously in a short time, potentially leaving lasting memories, also known as digital footprints.6

Cyberbullying takes various forms in different situations. For example, "flaming" occurs when a perpetrator uses offensive and violent language during online communication, and "trolling" involves provoking a person or group in a humorous but degrading manner. “Defamation” involves spreading malicious information to damage a victim's reputation. "Masquerading" is pretending to be someone else, usually the victim. Some other modern forms of cyberbullying include "outing" and "cyberstalking".7

In the digital environment, aggression can occur with or without the specific intent of the perpetrator to make it repetitive or targeted at a less powerful victim. For example, a single online comment by a user can easily be spread beyond the initial post.3

Several factors, such as a lack of peer support, emotional intelligence, violent behaviour, substance use, and access to social media and the internet, can influence the association between cyberbullying victimisation and various types of mental health disorders. Additionally, the increased prevalence of cyberbullying victimisation among female adolescents, leading to mental health issues and suicidal ideation, is reported in several studies.8,9

Most studies involving cyberbullying have been conducted with adolescents and secondary school students, assuming a later onset of access to social media and the internet. However, it is estimated that in 2016, 90.6% and 93.1% of children aged 10 and 11, respectively, were already internet users.5 The indiscriminate use of social media by young people who are still in a stage of social and emotional development is concerning.4 Chronic victimisation from early adolescence can be particularly alarming, potentially increasing the risk of further victimisation episodes and psychological problems.5

Thus, this research study was motivated by the need to conduct studies with younger children to analyse the prevalence of cyberbullying in this age group and to tailor intervention and prevention strategies accordingly.

The primary objective of this study was to analyse the prevalence of cyberbullying among children in the second and third cycles of basic education in schools within the city of Vizela. The investigation aimed to determine the most frequently implicated forms of cyberbullying in this age group and to explore the nature of behaviours related to cyberbullying from the perspectives of the perpetrator, the victim, and the bystander.

Methods

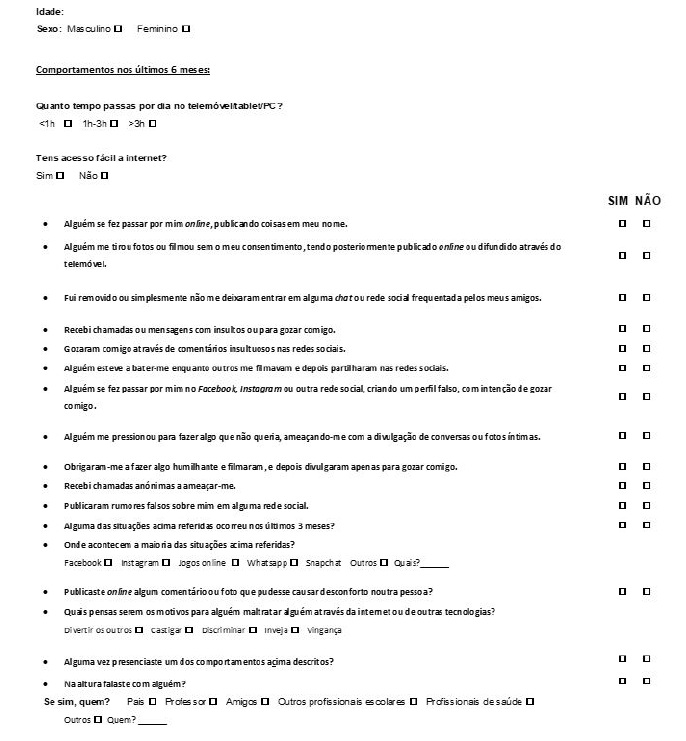

A cross-sectional observational study was conducted, with descriptive analysis of data collected through questionnaires distributed in second and third cycle basic education schools in the municipality of Vizela (Appendix A).

The study population included all young people attending the second and third cycles of basic education at schools in Vizela - Agrupamento de Escolas de Caldas de Vizela and Agrupamento de Escolas de Infias -during the 2022/2023 academic year.

Consent was obtained from a legal representative to participate in the study, through the signing of the Informed Consent Form (Appendix B) distributed beforehand. Children and pre-adolescents without Informed Consent or without permission to participate in the study were excluded.

An initial session was held to inform teaching and non-teaching staff about the current landscape of cyberbullying and the study’s objectives in determining the prevalence of this phenomenon (and its characteristics), which could help develop future preventive strategies. The study design and methodology were explained, and the Informed Consent Forms authorising participation in the study were handed over to the respective Class Directors. During a second visit to the schools, the researchers collected the Informed Consent Forms and distributed the questionnaires (Appendix A) to students who met the inclusion criteria.

To ensure maximum confidentiality, the questionnaires were anonymous, and students were instructed not to include any identifying information when completing them.

The researchers defined the following study variables: age; gender (male/female); time (in hours) spent on a mobile phone/tablet; and the cyberbullying questionnaire. This questionnaire included an adaptation of the Cybervictimisation Questionnaire,10 specifically designed for this purpose, which was later subjected to a pre-test that revealed easy understanding of the responses. The researchers chose to remove some items from the original version of the questionnaire and add new questions to assess the perspectives of the perpetrator and the bystander.

The collected data were recorded and subjected to statistical analysis using the SPSS® v22.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Chicago, Illinois, USA) software and Microsoft Excel® 2016. Pearson chi-square tests were conducted between the variables, with the authors setting statistical significance for p-values (test probability values) below 0.05.

Results

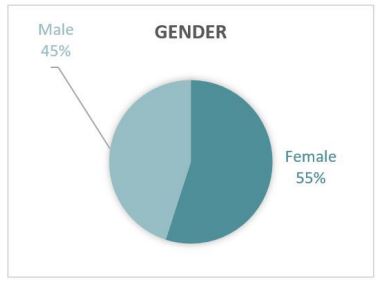

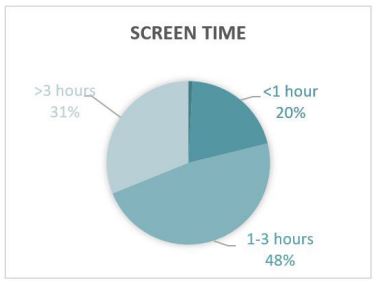

The study included a population of 1,235 students enrolled in the second and third cycle school during the 2022/2023 academic year. Out of these students, only 482 met the inclusion criteria defined by the researchers to participate in the study. From the sample of 482 students, ages ranged from 9 to 15 years, with a median age of 12 years, and a similar gender distribution-55% female and 45% male (Figure 1). Regarding daily screen time, 20.5% reported spending less than 1 hour, 47.7% between 1 and 3 hours, while 31.1% spent more than 3 hours per day (Figure 2).

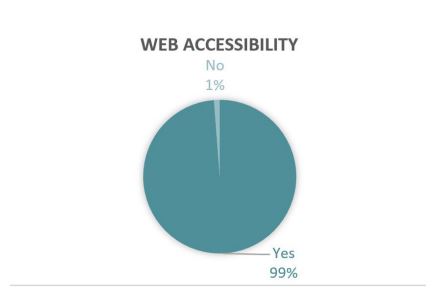

The vast majority reported having easy access to the internet, with only 1% responding negatively to this question (Figure 3).

Students were classified as victims of cyberbullying if they scored on at least one of the items corresponding to the categories described in the Cybervictimisation Questionnaire.10 Thus, the recorded prevalence in this sample was 30.9%, representing 149 students, with 34.9% of them reporting being victims within the last three months. The most frequently reported forms of cyberbullying in this population were: “I was removed from or simply not allowed to enter a chat or social network frequented by my friends” (47%), “I received calls or messages with insults or to make fun of me” (42%), and “Someone took photos or filmed me without my consent, later posting them online or sharing them via mobile phone” (35%).

In this study, a statistically significant higher prevalence of female victims was observed (61.8% were female, p = 0.046; 38.2% were male). Only 50% of the victims sought help, with 61% of those being female. Most requests for help were directed towards parents (53.4%) and friends (51.9%), followed by teachers (21.8%), other school professionals (8.3%), and other family members.

Potential “bullies” were identified as students who responded affirmatively to the question: “Have you ever posted a comment or photo online that could cause discomfort to another person?” (3.3%), with a median age of 12 years and a similar gender distribution. Despite this, 34.4% of respondents admitted to having witnessed cyberbullying. Of those witnesses, 77% reported the incident, with females again being more likely to report these behaviours (59.5% vs 40.5%). A statistically significant association was found between having previous experiences of cyberbullying as a victim and current behaviour as a perpetrator (70.6% of aggressors had been victims, p < 0.001).

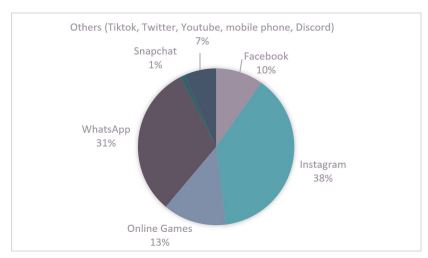

Regarding the digital spaces where these aggressions occur, Instagram was the most frequently mentioned platform, followed by WhatsApp (Figure 4). The most commonly identified reason by students for acts of cyberbullying was "Jealousy" (55.4%), with "Discrimination" and "Entertaining others" also highlighted as causes.

In the subsample of students who experienced cyberbullying, the percentage of aggressors was considerably higher compared to students who had never been exposed to it, with a statistically significant relationship (8.1% vs 2.4%, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Adolescence is a transitional period between childhood and adulthood, characterized by distinctive life-cycle traits, during which significant biological, cognitive, and psychosocial changes occur. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines pre-adolescence as the period between 10 and 14 years of age, corresponding to the second and third cycles of Portuguese schooling (years 5 to 9).

As observed in this study, exposure to digital technology in this age group is almost universal (98.8%), with a cyberbullying prevalence of around 31%, an alarming rate of victimization at a crucial stage of social, psychological, and emotional development. Unlike face-to-face bullying, which is more prevalent among males,11 this research, similar to the existing literature, documents a higher prevalence of cyberbullying among females, with a statistically significant relationship (p = 0.046).

Regarding the most frequently reported forms of digital aggression in this age group, "ostracism/exclusion," the act of intentionally excluding others from an online group, stands out, followed by "flaming" or "roasting," which involves a personal and direct attack with insulting, destructive, and mocking messages in a forum or social group.12

In line with current evidence, this study also highlights the predominance of females as the population group most frequently reporting and seeking help, both as witnesses and victims. Despite this, about 50% of victims do not seek help from an adult, which can lead to a cycle of uncontrolled and irrational violence, with damaging effects on the child's self-esteem and self-determination.

As witnesses, most of the pre-adolescents in the study sample reported and sought help (77%), with parents and school professionals being the most frequently involved parties.

The investigation also revealed that victims are more likely to become aggressors than children who have never been exposed to cyberbullying, with the relationship between aggressors and victimization being statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Rice et al. correlate increased screen time with a higher risk of cybervictimization; however, the researchers in this study did not find a statistically significant relationship between accessibility and screen time with the degree of victimization.

Overall, cyberbullying can have a profound emotional impact on individuals, often independent of traditional forms of bullying.3 This underscores the need for comprehensive strategies to address and prevent cyberbullying, as well as support systems for those who have experienced it.

Being a target of bullying during adolescence is considered a global public health issue related to the psychological development of adolescents, which often persists into adulthood. Multiple studies document that adolescents victimized by their friends or peers are at greater risk of mental health problems, including lower self-esteem, feelings of loneliness, depression, suicidal ideation, self-harm, and aggression towards others.8

A multidimensional approach involving various stakeholders is necessary to reduce cyberbullying. At the school level, policies should be developed and implemented to ensure a safe school environment with mental health services available on-site or through appropriate referral systems for both victimized students and aggressors.9

Studies are needed to analyse the relationships between victims and aggressors and the long-term consequences of cyberbullying for both parties involved. Ongoing research is required to keep pace with the evolution of cyberbullying in the context of constantly changing digital apps and technological platforms. Qualitative research is needed to provide a deeper understanding of the context, content, and effects of cyberbullying. Interventions mediated through digital channels are especially promising as they can leverage the rapid increase in technology use among young people and be delivered through the same platforms where cyberbullying occurs.9

There are three important limitations in this study that should be highlighted and discussed. First, as a cross-sectional study, it cannot establish causal relationships. Additionally, the sample includes only one geographic area from a single municipality, which may limit and influence the extrapolation of results to the national population. Lastly, the inability to characterize the population not included in this study (due to the lack of legal guardian consent) may underestimate the actual prevalence of cyberbullying, as potential victims, aggressors, or witnesses may not have been included in this study.

Conclusion

Current evidence shows significant variations in the prevalence of cyberbullying; however, increased accessibility to digital media has led to growing exposure to victimization at increasingly younger ages.

Technological globalization makes cyberbullying an issue that exceeds the limits of traditional bullying, with serious implications for public health. This study identified a high prevalence of cyberbullying and raised awareness of certain concerning situations, such as the high risk of victims potentially becoming future aggressors and the fact that only half of the victims report the violence they experience.

The lack of scientific information on this issue in Portugal highlights the urgent need for further research to develop effective preventive measures in the near future.

Awards

The research received the 1st prize for Best Oral Communication presented at the 28th National Patient Care Conference, on February 23, 2024.

Authorship

Vanda Melo - Formal analysis; Investigation; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Visualization; Writing - original draft and Writing - review & editing

Pedro Pacheco - Resources; Visualization; Writing - original draft

Mariana Portela - Conceptualization; Data curation; Methodology; Project administration; Validation

Sandra Costa - Conceptualization; Data curation; Methodology; Validation

Helena Ribeiro - Conceptualization; Data curation; Methodology; Supervision and Writing - review & editing