Introduction

Unifying organic and inorganic materials enhances their electrical and conducting properties, and facilitates their usage in energy storage devices. Electron transmission due to oxidation or reduction in PANI chain increases its affinity to many chemical molecules, thus limiting its electrochemical performance. Spontaneous charge transfers interactions occurring in the polymer backbone are complex and difficult to control 1,2. A potential way of increasing PANI’s electrochemical properties is to incorporate an inorganic substance into its matrix 3-9.

The combination of metal oxide nanomaterials and PANI has proved to provide SC electrodes with very high energy and power density, which possess synergistic properties that are absent in each individual component. The synergistic effect facilitates a path for electron density transformation through distinct reaction sites on the electrode surface, by controllable interactions. The drastic enhancement of electrochemical properties and charge-discharge characteristics of the hybrid material depend not only on the synergistic effect of the constituents but also on their combined morphology and interfacial characteristics 10,11.

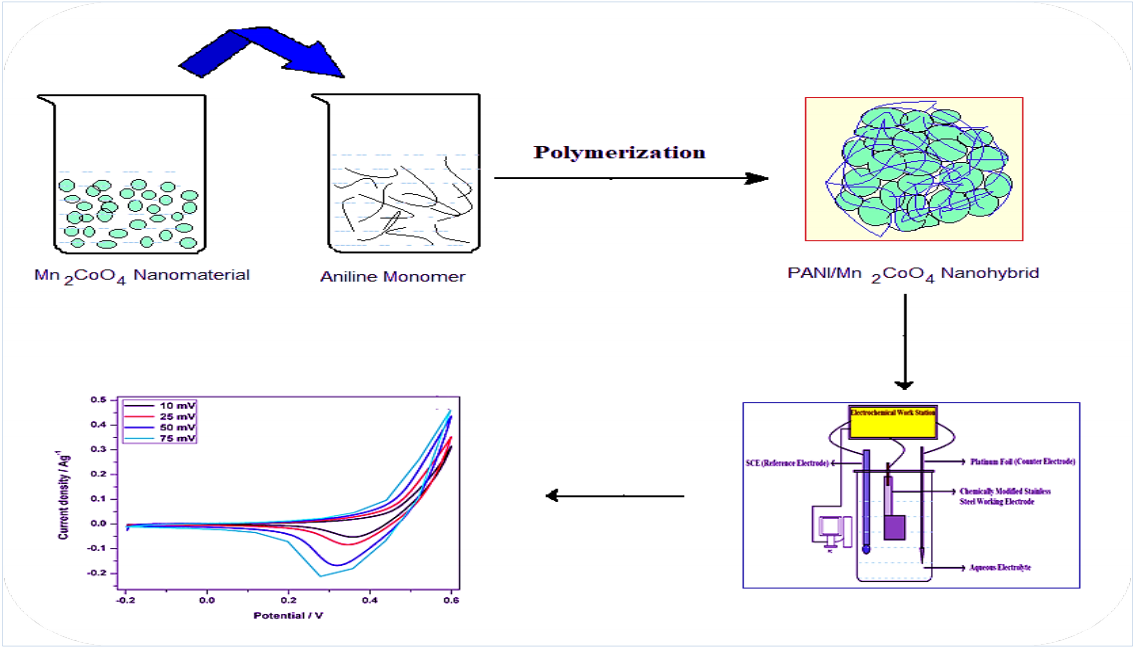

MnCo2O4 has been reported as a potential material for energy storage 12-15, although its electrochemical performance is reduced at higher j values. So, there is the need to combine metal oxides with other materials, to improve their capacity and stability. Herein, NHP from PANI/Mn2CoO4 was synthesized by a simple chemical polymerization method. Its structural properties were studied by various physicochemical characterization methods, such as FT-IR, X-RD and SEM. Electrochemical and charge-discharge results revealed PANI/Mn2CoO4 enhanced SC potential.

Experimental method

Synthesis of NHP from PANI/Mn2CoO4

NHP from PANI/Mn2CoO4 was synthesized by surfactant-assisted dilute polymerization method. The dopant Mn2CoO4 nanomaterial was prepared by a solution combustion method reported in literature 16. The monomer solution was prepared by dissolving 0.2 M pure aniline in 100 mL/1 N HCl. DBSA and triton X-100 (2:1 mole ratio) surfactants were added to it, and mechanically stirred for 1 h. Mn2CoO4 (5 wt%) was suspended in 100 mL/1 N HCl, and stirred for 30 min. Then, these two solutions were mixed together and continuously stirred for 1 h. (NH4)2S2O8 was dissolved in a 1 M (50 mL) HCl solution, and added dropwise to the monomer-surfactant solution, with continuous stirring. The whole polymerization process was carried out in ice cold conditions (0-5 ºC), and the stirring proceeded for about 6 h. The product was filtered and washed several times with distilled water, until the filtrate became colorless. Then, the solid hybrid polymer was rinsed with HCl aqueous solution and methyl alcohol. Finally, the green colored PANI/Mn2CoO4 NHP were filtered and dried under dynamic vacuum, at 80 ºC, for 8 h.

Preparation of the modified electrode

The slurry was prepared by mixing 80 wt% PANI/Mn2CoO4 with 10 wt% carbon black and 10 wt% PVdF in NMP, respectively. Then, the mixture was uniformly coated on a clean surface (1 × 1 cm) of the stainless-steel plate. Chemically modified PANI/Mn2CoO4 was heated at 70 ºC, to remove the organic solvent, and then used as working electrode. Pt foil and SCE were the counter and reference electrodes, respectively. CV scan (Versa STAT MC Electrochemical Workstation - Princeton Applied Research) was performed at different SR (10, 25, 50 and 75 mV/s-1), with a wide E window from -0.2 to 0.6 V, in a 1 M KOH electrolyte solution. GCD tests were carried out at different j values, to study the cyclic stability and power characteristics of PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode. Capacitive properties, such as specific capacitance, columbic efficiency, power and energy density were calculated by standard equations reported in literature 17-19.

Results and discussion

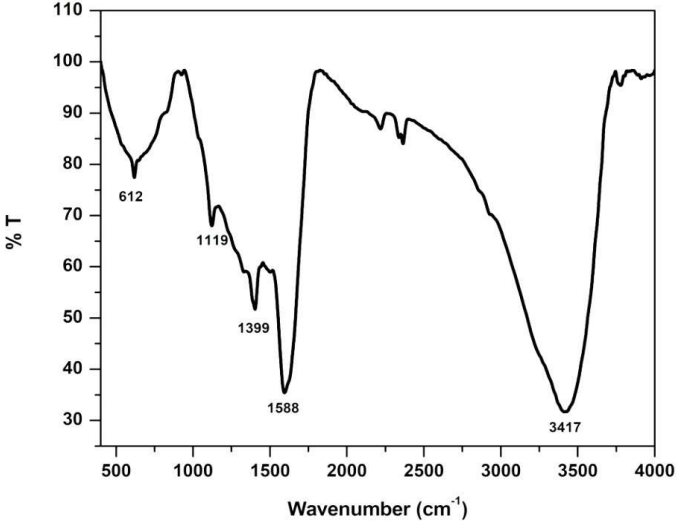

Fig. 1 shows FT-IR spectra of PANI/Mn2CoO4. It is clear that the spectrum contains a number of characteristic vibrations originating from both Mn2CoO4 dopant and PANI host.

N=Q=N ring vibration mode appeared at 1119 cm-1. C=C for quinonoid and benzenoid rings occurred at 1588 and 1399 cm-1, respectively 20-22. The sharp intense peak that came at 612 cm-1 was assigned to Co-O bonding, and confirmed Mn2CoO4 incorporation into PANI matrix. Wider and broader band centers at 3417 cm-1 were attributed to N-H and O-H vibration stretching modes. This broad vibration confirmed hydrogen bond formation between Mn2CoO4 nanoparticles and N-H groups of PANI 23.

However, peaks obtained in NHP from PANI/Mn2CoO4 slightly shifted and are different from those in pure Mn2CoO4 and PANI. This significant change in stretching vibrations suggests that there was an interaction between PANI and Mn2CoO4.

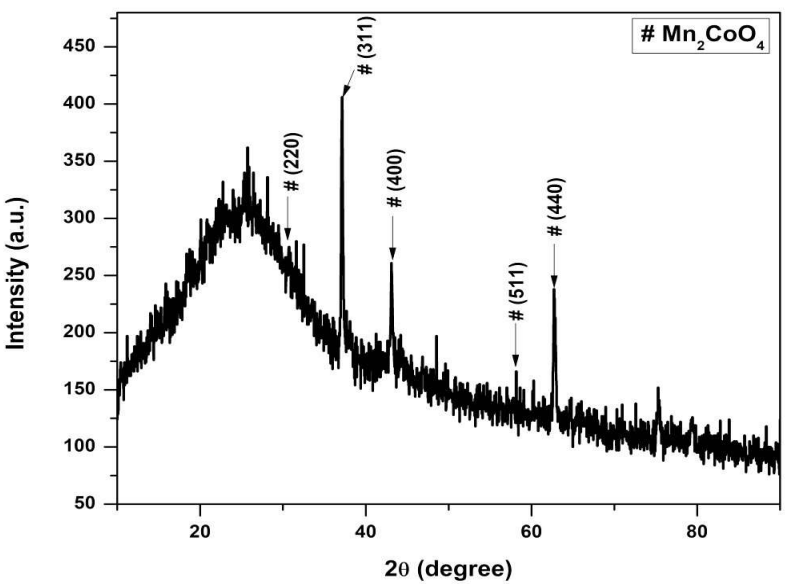

X-RD pattern of NHP from PANI/Mn2CoO4 is shown in Fig. 2. The intense peaks that appear in X-RD indicate that PANI’s increased crystallinity was due to Mn2CoO4 addition.

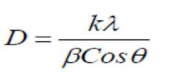

Most of the intense peaks usually obtained in the case of pure Mn2CoO4 nanoparticles (2θ = 31.8340, 34.4853, 36.3303, 47.6017 and 56.6575) are present in the hybrid material, which is consistent with standard JCPDS values (No. 26-0168). The peaks at 19.7, 23.4, 29.0, 31.3, 32.9, 38.6, 47.1 and 57.8º are characteristic from PANI (JCPDS No.53-1717) 24. PANI amorphous nature was improved by Mn2CoO4 incorporation into its matrix. The sharp peaks that appear in X-RD depict the high degree of crystallinity due to extended π conjugation in the hybrid polymer 25,26. The average particle size (D) was calculated using Debye-Scherrer eq. (1):

(1)

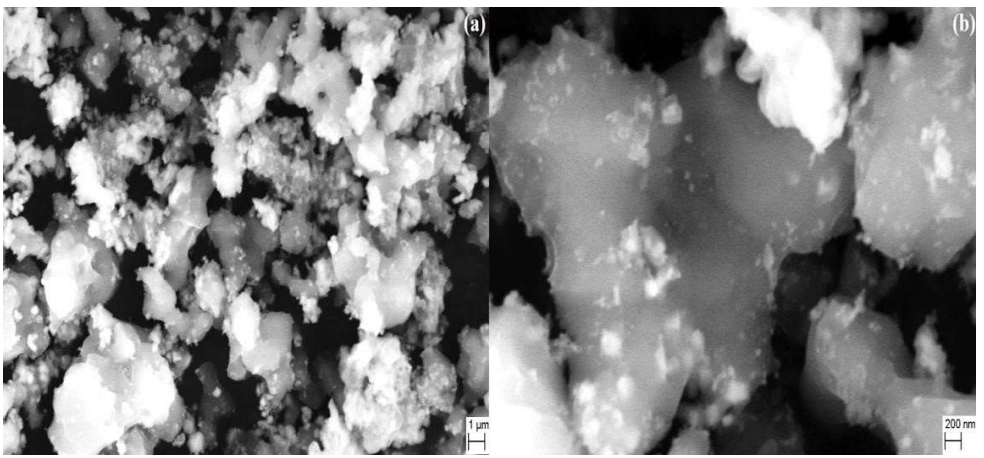

where k is 0.9 (constant), λ is Cu-kɑ radiation wave length (1.5418 Å), β is FWHM in radians, and θ is Bragg’s diffraction angle at maximum intensity. PANI/Mn2CoO4 average particle size (60 nm) was calculated from the most intense XR-D maxima, by applying this equation. SEM images of PANI/Mn2CoO4 are shown in Fig. 3 ((a) and (b), where the particles are clearly seen, highly aggregated, and have a porous nature.

The average grain size was estimated to vary from 40 to 100 nm. The addition of nanosized Mn2CoO4 to the PANI matrix reduced its crystalline size, and caused agglomeration. The uniformity of PANI/Mn2CoO4 individual particles was disturbed due to particle aggregation. The hybrid polymer core was made up of PANI, and its surface had encapsulated Mn2CoO4. The interaction between Mn2CoO4 and PANI prevented the polymer over aggregation during the hybrid formation, and facilitated a synergistic effect, which is a key factor in enhancing its electrochemical performance.

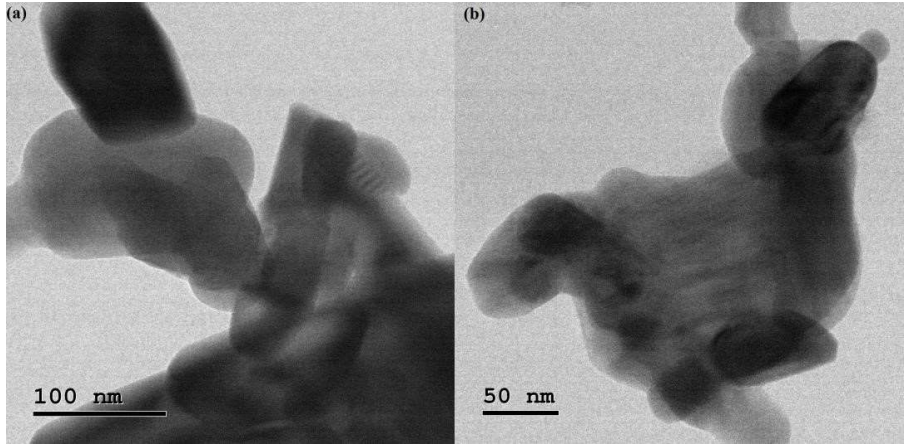

PANI/Mn2CoO4 formation was confirmed from TEM images (Fig. 4 - (a) and (b).

TEM images show that NHP particles do not have a uniform size and shape, due to Mn2CoO4 nanoparticles incorporation into PANI matrix, which significantly changed the material morphology and size. Mn2CoO4 appeared as dark black particles well embedded into PANI matrix whole surface.

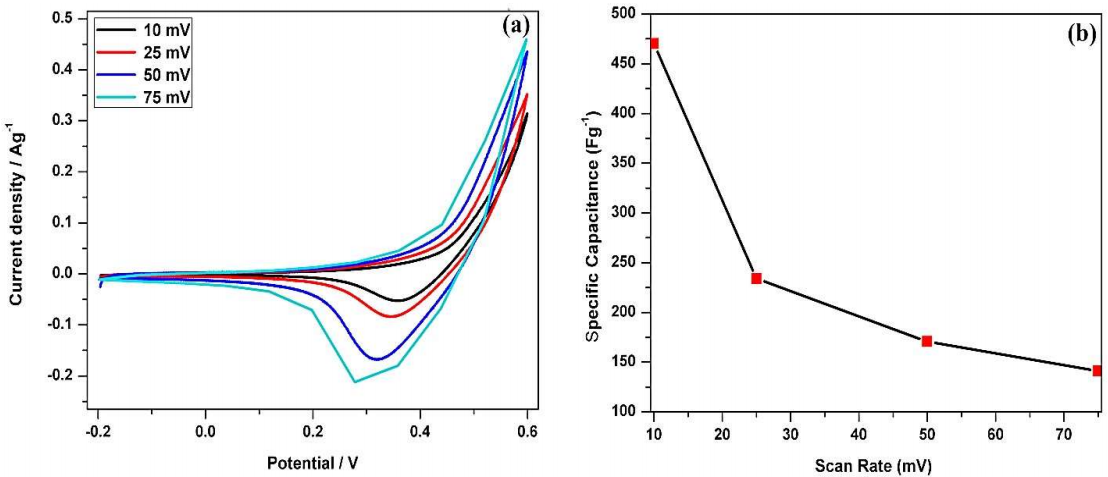

PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode capacitive properties were qualitatively evaluated by CV scanning, at different SR, in a 1 M KOH electrolyte solution, within E window from 0.2 to 0.8 V (Fig. 5a).

Figure 5: (a) CV of PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode in a 1 M KOH aqueous solution; (b) Plot of SR vs. specific capacitance.

CV results at all SR (10, 25, 50 and 75 mVs-1) are similarly shaped, with good reversibility, and confirm the electrode pseudo capacitive nature. However, CV curves did not have a regular rectangular shape 27, due to the large number of redox reactions by the conjugated bonds present in PANI’s chain 28. The peak current increased significantly when SR changed from 10 to 75 mV/s1, due to the confinement of the active material on the electrode.

A wide rectangular area in the CV indicates the higher electro capacitive nature of the PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode and its very high specific capacitance value. The CV forward and reverse sweeps confirm the existence of all three different forms of PANI. Fully reduced leucomeraldine was observed at negative E of -0.2 V. During the sweep towards positive E, leucomeraldine was oxidized and converted into emeraldine form, at E from 0.2 to 0.35 V. Further oxidation occurred at more positive E (from 0.5 to 0.6 V), and yielded pernigraniline, PANI completely oxidized form 29-32.

The resulting current under CV curves was used to calculate the active material capacitance values at all four SR. PANI/Mn2CoO4 specific capacitance values were 470, 234, 170.5 and 141.5 Fg-1, respectively, at the SR of 10, 25, 50 and 75 mV/s-1, respectively.

Fig. 5b depicts PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode variation in its specific capacitance, with respect to SR. It was seen that specific capacitance values steadily decreased with increasing SR from 10 to 75 mV/s-1. E sweep was slow at the lower SR. This facilitated the diffusion of a greater number of ions into the electrode, which increased the utility of the active material present on its surface. The specific capacitance values observed at higher SR (25, 50 and 75 mV/s-1) were relatively much lower, due to quick E sweep, which reduced ionic diffusion rate. The synergistic effect between Mn2CoO4 and PANI accelerated the reaction rate at the electrode-electrolyte interface, which facilitated the occurrence of redox reactions 33.

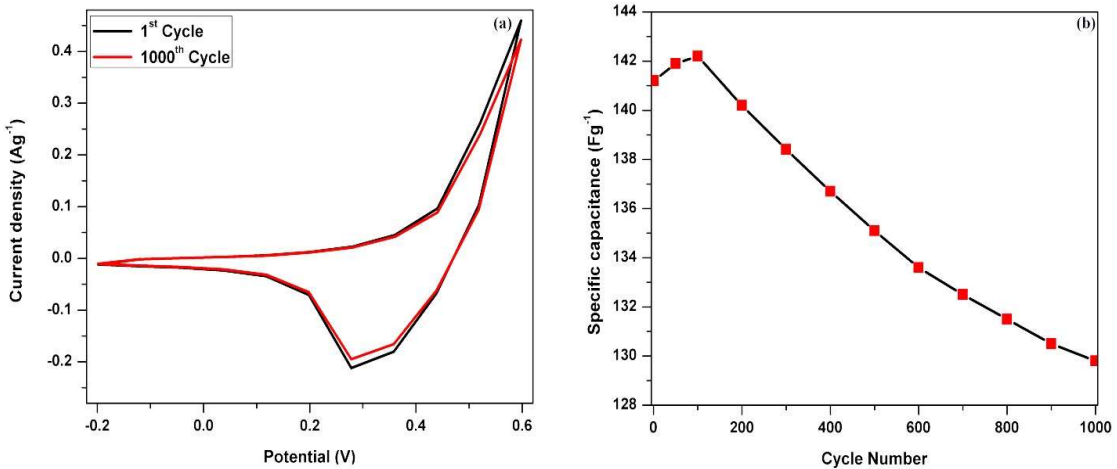

Stability is the key factor for any electrode material that can be used commercially in SC applications. PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode electrochemical stability was evaluated by continuous cycling up to 1000 cycles, at a SR of 50 mV/s-1.

Fig. 6a shows CV curves of 1st and 1000th cycles of PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode operated within E window from -0.2 to 0.6 V.

X-RD shape was not distorted even after 1000 continuous cycles. This indicates that the loss of active material was much lower during the cycling and was not affected by the reactions occurring at the electrode surface.

Figure 6: (a) 1st and 1000th cycle of PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode in a 1 M KOH aqueous solution; (b) Plot of cycle number vs. specific capacitance.

Fig. 6b shows specific capacitance of PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode as a function of cycle number. The specific capacitance gradually rose during the initial cycles, and showed a 5% increase after 100 cycles. The brisk ionic diffusion on PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode surface increased the porosity level and, thus, the specific capacitance value 34. After reaching the maximum at the 100th cycle, the specific capacitance value steadily decreased during consecutive cycles. The capacitance fading was weaker after 650 cycles, and almost flattened at the 1000th cycle. The decrease in capacitance was expected even after 1000 cycles, but its fading may be insignificant. The capacitance retained by the active electrode material after 1000 successive cycles was 96%. The repeated redox reactions continuously occured during the long cyclic process, and generated the swelling effect which led to PANI backbone slight degradation, reducing specific capacitance value 35,36. PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode hybrid material withstood about 1000 cycles without any significant decrease in capacitance, indicating its superior stability in energy storage applications. Mn2CoO4 incorporation into PANI effectively increased the polymer material stability and its capacitance retention ratio.

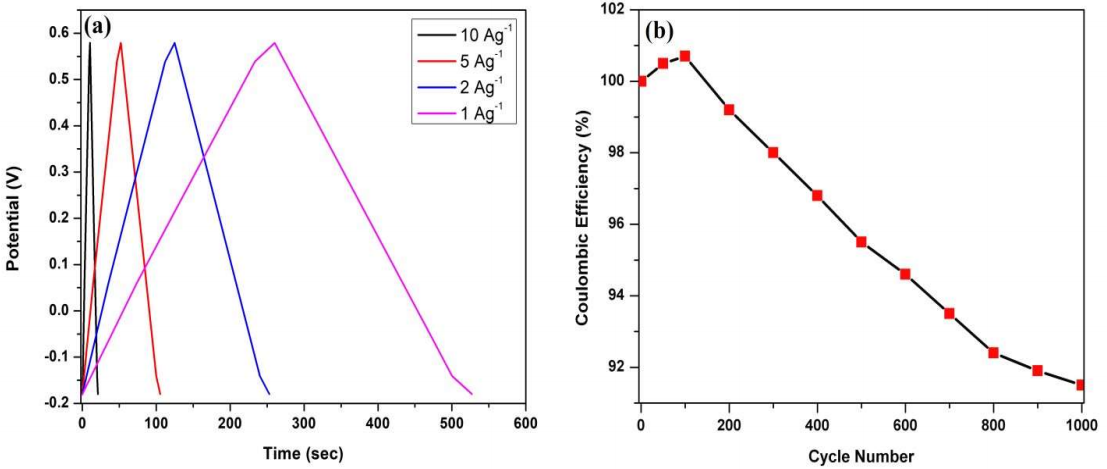

Fig. 7a shows GCD profile of PANI/Mn2CoO4 hybrid electrode at an E window from -0.2 to 0.6 V, with different j values. The linear charge-discharge curves clearly indicate PANI/Mn2CoO4 perfect reversibility and capacitive nature.

Figure 7: (a) GCD curves of PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode in a 1 M KOH aqueous solution at different j values; (b) plot of cycle number vs. columbic efficiency.

The amount of charge stored on the PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode was calculated by integrating the amount of current discharged during a complete charge-discharge cycle. The specific discharge capacitance calculated from the charge-discharge curve was 141.2 Fg-1, at the SR of 75 mV/s-1, which indicated the high capacitive nature of the hybrid electrode, even at higher SR cycling. The energy and power density measured at j of 2 mA/cm-2 were 2.28 and 762.6 wk/g-1, respectively. PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode energy density was lower than that from the values of pure Mn2CoO4 electrode reported in literature. The decrease in PANI/Mn2CoO4 energy density was mainly due to the short discharging time during the cycling. However, its measured power density value was much higher than that from bare PANI 37,38 and metal oxide doped PANI nanocomposites 39,40.

The relation between the columbic efficiency and cycle number is shown in Fig. 6b. The columbic efficiency of the PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode after 1000 cycles was found to be 87.1%, which shows its high charge efficiency and superior electron transfer rate, even after 1000 cycles.

Conclusion

This work described the synthesis of NHP from PANI/Mn2CoO4, by a surfactant assisted chemical polymerization method. Physicochemical methods such as X-RD, FT-IR and SEM were employed to characterize PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode. Its highest capacitance value was 470 Fg-1, at a SR of 10 mV/s-1. The electrode also displayed a maximum energy density of 2.28 Wh/kg-1 and a maximum power density of 762.6 W/kg-1, at j of 2 A/g-1. This power density value was higher than that of pure PANI or bare metaloxide-based SC. PANI/Mn2CoO4 electrode superior electrochemical performance was due to the surface activation induced by the synergistic contribution between them.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript never received any funding, grants and support from the persons, agencies, industrial or commercial parties and declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contributions

M. Shanmugavadivel: sample preparation; carried out the experiment and performed calculations with results. M. Subramanian: designed and developed the research work; wrote the manuscript with support from authors. V. Dhayabaran: supervised and validated the research findings.

Abbreviations

A/g: applied current (A)/amount of electrode material (g)

CV: cyclic voltammetry

DBSA: dodecyl benzene sulphonic acid

E: potential

Fg-1: specific capacitance

FT-IR: Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

FWHM: full width of half-maximum

GCD: galvanostatic charge discharge

HCl: hydrochloric acid

j: current density

JCPDS: Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards

KOH: potassium hydroxide

Mn2CoO4: manganese cobalt oxide

(NH4)2S2O8: ammonium persulphate

NHP: nanohybrid particles

NMP: N-methyl-2-pyrrolidine

PANI: polyaniline

PVdF: polyvinylidene difluoride

redox: reduction-oxidation reaction

SC: supercapacitor

SCE: saturated calomel electrode

SEM: scanning electron microscopy

SR: scan rate

TEM: transmission electron microscopy

XRD: X-ray diffraction

Wh/kg-1: gravimetric energy density