Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Sociologia

versão impressa ISSN 0872-3419

Sociologia no.tematico8 Porto dez. 2018

https://doi.org/10.21747/08723419/soctem2018a4

ARTIGOS

The touristic Porto – gazing over the city

O Porto turístico - olhares sobre a cidade

Le Porto touristique - regards sur la ville

El Oporto turístico - miradas sobre la ciudad

Tiago Miranda

Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto

Endereço de correspondência

ABSTRACT

This article is the outcome of a research in Sociology about tourism in the city of Porto in the year of 2015, viewed through the emerging city break modes of travel. We endeavored to understand, through the foreign tourists' gazes as well as from images that shape the city as touristic, whether Porto was an “authentic” city, unlike any other, in the context of rampant growth tourism has seen there and in Portugal during the first two decades of the twenty-first century, subject to a larger European circuit. The most relevant conclusions point toward the touristic and global turn of Porto, with ever-growing visitors, and grappling with potentially nefarious effects derived therefrom; but keeping - in the eyes of the foreign tourist who visits it – its authenticity, unique in its own way, and in the distinct way of each one who experiences and beholds this city.

Keywords : city; tourism; the tourist gazes.

RESUMO

O presente artigo resulta de uma investigação sociológica sobre o turismo na cidade do Porto no ano de 2015, entendido na sua configuração emergente de city break. Procurou-se compreender – a partir dos olhares de turistas estrangeiros que a visitam, bem como de imagens que a constroem como destino turístico – se o Porto seria uma cidade “autêntica”, diferente das outras, no contexto de crescimento galopante que o turismo regista em e para Portugal nas primeiras duas décadas do século XXI, subjacente a um circuito europeu mais amplo. As conclusões mais relevantes apontam para a viragem turística e global do Porto, recebendo cada vez mais visitantes, deparando-se com efeitos potencialmente nefastos daí derivados; mas mantendo – aos olhos do turista estrangeiro que o visita – a sua autenticidade, única à sua maneira, e à maneira distinta de cada um que contempla e vivencia esta cidade.

Palavras-chave : cidade; turismo; olhares dos turistas.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article est le résultat d'une recherché en sociologie sur le tourisme dans la ville de Porto pendant l'année 2015, vu à travers de nouveaux modes de tourisme urbains, comme le city break. Nous avons essayé de comprendre, à travers les regards des touristes étrangers et les images qui font la ville touristique, si Porto était une ville “authentique”, pas comme les autres, dans le contexte de croissance rapide que le tourisme a connu au Porto et au Portugal pendant les deux premières décennies du XXIe siècle, soumises à un circuit européen plus large. Les conclusions les plus pertinentes pointent vers le virage touristique et global de Porto, recevant de plus en plus de visiteurs, rencontrant des effets potentiellement néfastes qui en découlent ; mais en gardant – aux yeux du touriste étranger qui la visite – son authenticité, unique à sa manière, et à la manière distincte de chacun qui contemple et expérimente cette ville.

Mots-clés : ville; tourisme; regards des touristes étrangers.

RESUMÉN

Este artículo es el resultado de una investigación en sociología sobre el turismo en la ciudad de Oporto en el año de 2015, vista a través de los modos emergentes de viaje city break. Nos esforzamos por comprender, a través de las miradas de los turistas extranjeros y de las imágenes que le dan forma turística, si Oporto era una ciudad “auténtica”, como ninguna otra, en el contexto del galopante crecimiento que el turismo ha visto allí y en Portugal durante las dos primeras décadas del siglo veintiuno, sujetos a un circuito europeo más grande. Las conclusiones más relevantes apuntan hacia el viraje turístico y global de Oporto, recibiendo cada vez más visitantes, encontrándose con efectos potencialmente nefastos derivados; pero manteniendo – a los ojos del turista extranjero que lo visita – su autenticidad, única a su manera, y a la manera distinta de cada uno que contempla y vivencia esta ciudad.

Palabras-clave : ciudad; turismo; miradas de los turistas.

Introduction

This article retraces the footsteps of a sociological research made by the author within the scope of his master's degree thesis (Miranda, 2015): the underlying purpose is to condense its findings in a more approachable form. The research itself was about tourism in the city of Porto, in Portugal, having taken place there throughout the year of 2015. The main objective was twofold, looking to find out, through the gazes of the foreign tourist, what makes a city to be authentic and different from others – in our case, Porto; and, on the other hand, to explore tourism and globalization's roles in the making of their representations of the same city. The specific nature of our work dwelled in urban tourism, and in particular, in the emerging configurations of city break, a touristic trip-taking noted for its shorter length and increasing popularity amidst the choices of foreign visitors to Porto. Accordingly, this city has come to be established of late as a touristic destination of growing appeal to the foreigner, gradually reinforcing its presence in the tourist trails of Europe since the middle of the first decade of the twenty-first century: in this milieu and through this relationship, “city break” is seen as decisive. Nevertheless, the city and tourism sprang forth as fundamental themes, regarded as two mutually influenced phenomena, at the same time placing the tourist as a favored agent in that dialectical context – their gazes would step in as a metaphor of their own representations, a way to translate the city. Was Porto a unique city in the background of tourism and globalization?

We wanted to know where the foreign tourists to Porto were coming from, how they felt, the sentiments created and maintained with the city. Would they travel so much – a chance granted by city break modes of voyage – insofar as to reduce the charm of any given city? Would they be influenced during the bustle of their visit by previous, stereotyped, viewings of the destination in the Internet and mass media? How would the act of taking photos in the visit per se intersect with their imagination and general practices of tourism? Through these and other questions we strove to ascertain the perceived uniqueness (or authenticity) of Porto, whether that remained unscathed in the vortex of modern urban tourism, or otherwise levelled and tarnished regarding other visits made to different cities by the same tourists.

1. Manifest affinities between the city, tourism and the tourist

First things first, like packing up before a trip. In the briefest of sociohistorical framings, tourism knows its first inception as the British aristocracy's grand tour between the seventeenth and eighteenth century: with several sojourns across Europe, its constituents hoped to garner a universal education and spiritual clarity whilst socially distinguishing themselves from other groups who could not yet make this new kind of journey (Gagliardi, 2009: 246-248). Despite the rest of Europe's nobility following suit, the next breakthrough only came in the nineteenth century, with the advent of a trip more concerned with leisure rather than ethereal improvement. As the Industrial Revolution began, those who held the means of production found themselves with increasing wealth; the bourgeois class, then, could and would spend that newfound wealth in leisure and joyful travelling (Gagliardi, 2009: 248-249), adjoined by myriad advances in the means of transport and spatial displacement (Lash and Urry, 1998). Capitalism continued to grow, and at the outset of the twentieth century, tourism did so too: it is truthfully born here, in organized capitalist fashion (Gagliardi, 2009: 250-251), wherein a conjunction of collective and individual rights (better wages and vacations, for example) widens the possibility of travelling to other social groups (Fortuna, 1999a: 48-51). With Bauman, we argue tourism was a human activity nestled in the outskirts of European society, undertaken by few, before becoming a central facet of contemporary social life, engaged by many (Bauman, 1996: 29).

One of the theoretical anchors of this research was set by Urry (2002), and the “tourist gaze” he drew upon to analyze tourism and its inherent travelling. Tourism as a “visual contrast” tried to place the act of practicing tourism as different from everyday social life through eyesight: by having, living and seeing common experiences in the latter, the former would elicit extraordinary experiences by providing a series of different visual elements for the tourist to set his gaze upon. Tourism, therefore, carved a boundary between the experiences it encouraged and the recurring, perhaps even methodical, everyday life of people; first and foremost, through eyesight, which nonetheless served as a gateway for the rest of the human senses to be enlivened by a distinct set of circumstances. More so than tourism as an illusion, as purported by Boorstin (1992), whereupon touristic sites presented a forged event ready to be consumed by hapless visitors, and tourism as a means of proximity between visitor and visited in staged authentic locales where the first can quench his curiosity about the second, as defended by MacCannell (1999), the tourist gaze rose to us as a more suitable conceptual framework which to encompass contemporary urban tourism with.

In Portugal, in spite of some travel literature in line with the bourgeois kind of journey, written by famous novelists like Eça de Queiroz (Cunha, 2010: 129-130), amongst others, tourism began institutionally with the foundation of the Sociedade Propaganda de Portugal in 1906, a united effort of both republicans and monarchs to develop tourism indoors and its innate economic potential (Cunha, 2010: 131). Notwithstanding this pioneer movement, tourism moderately grew in the coming decades, bereft of political support (Portugal limped through a dictatorship of nearly 50 years, from 1926 to 1974, a system mostly incompatible with international openness), a professional body of individuals and ideas. Only during the last three decades of the twentieth century, and the following of the twenty-first, did Portugal grow in quantity and quality in terms of touristic flows, supply and demand (Moreira, 2008: 185-205). Considering recent data, Portugal has built itself into a “touristic destination” by excellence, diversifying the visages it can take (urban, countryside, business, enotourism, to name a few) as well as the outbound markets it can attract (a type of tourism for each type of tourist). Tourism in 2013 was accountable for 16% of Portugal's gross domestic product, a driving (and growing) force in the national economy (Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos, 2015: 113-114). Porto, in the same vein as its national counterpart, found a stronger touristic leaning in the decade of 1980 thenceforth (Silva, 2007: 15-18). Beginning in earnest in the decennium of 1990, the city managed to redefine its local resources outwards, entering headlong in the international network(s) of culture and tourism: to this much contributed the selection of its historical centre as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 19961 ; the designation, made by the European Union, to be the European Capital of Culture in 2001 (Silva, 2007: 18-19; 26-27); and the growth in the Internet marketing of its touristic assets after the millennium switchover (Azevedo, 2007: 251-259). Following new patterns of national segmentation, “city break” thus emerges as a defining touristic product for the city of Porto during the first decade of the twenty- first century and beyond, remarkable for being short, flexible and discretionary, finely adapted to growing individual expenses related to leisure. Besides having a hand in rejuvenating different urban landscapes strongly in favor of city break, this type of journey redraws the European travelling map, discovering and cementing new territories where tourists can embark to (Dunne, Flanagan and Buckley, 2010).

Tourism does not happen in a vacuum: in our case, “city break” was caught on the horns of an intricate urban landscape. We argued, following Fortuna (2001: 3-4; 23), that the city of the twenty-first century was, within itself, a redoubt of innumerable cities, laying bare the multitude of its significances and spaces, crisscrossed and continually overlaying; fragmented and hybrid, no longer the uniform counterpart of the rural countryside (if it ever was). The “touristic city” would be one of these cities-within-the-city, one more way of making and consuming the city, side by side with the remainder of urban territories it encircled, more often than not in discord rather than in harmony (Fortuna and Leite, 2009: 7). Following these thoughts, we laid the stress on the differing manners urban space could be used by social agents. Lefebvre (1991) viewed space as both the producer and product of social life: it was a representation, as much as it could be projected and designed by architects and urbanists; and through social use it was also a living space, where individuals carried out their lives, conforming or nonconforming to what was planned beforehand. In regards to tourism, “touristic places” in any given city are meant (“designed”) to be lived and trodden by tourists, but, on the other hand, the tourists themselves may feel them inadequate, challenging the homogenization of spaces created for them by deviating to other, less touristic, urban pockets (Lopes, 2002: 21) (which, in turn, become “touristic” not through the original act of a handful of urban planners or policymakers, but because of reiterated action/use of passing tourists). This is profoundly linked, as we viewed it, to the heterotopies of Foucault (1984), or the counter-place opposite to the place we perceive as real, whereupon the first is within the limits of the second but comes from outside of it. Tourists, in general, carry their own images of a given place, furthered by their imagination and the curiosity of previewing the destination; when that core of images does not match what is truly found and lived there, the tourist can, and probably will, reinterpret the space around him. Through different usages of (urban) space, we argued that it was always an unfinished matter, ready to be employed again and again by social agents.

Taking heed of what was said earlier about Porto's touristic disposition, cities that strive to become “global” endeavor to monetize their local resources (like their historical heritage and other equipment) in order to capture overseas mobility flows, of which tourism is a prime example (Fortuna, 2001: 14-15). In a competitive, capitalist world, cities henceforth become much like regular, private enterprises, building corresponding brands (like, in our case, “Porto Ponto” or just “Porto.”2 ), seeking success, profits, investors, recognition (Ferreira, Rua, Marafon and Silva, 2013: 9; 13). Leaning on Choay's (1999) important remarks about the subject, we beheld the historical centre of Porto as having been redefined as merchandise, revalued when it was undervalued, preserved when it was supposedly about to be forgotten. Enveloped by the idea of “if it's old, it's valuable”, this particular urban space is later embellished, more palatable for consumption, viewed and viewing itself as more of a commodity than history or culture. Regardless of the pessimism imbued in these arguments, they provide an apt context in which to perceive World Heritage Site declarations by UNESCO: this institution consecrates historical locales as worthy of being preserved, thus allowing their entrance into a so-called “authenticity market” (Fortuna, 1999a: 66). These places are, so to speak, thoroughly globalized at this moment, transferring their local, perhaps unknown, uniqueness to the global tribune; and through that process, their authenticity is debased by what is necessarily added and invented by way of tourism. Ultimately, Porto gains legitimacy as a brand and touristic destination – it is more sought after than before.

In our research, we tackled this subject through Benjamin's (1992) reasoning about the aura of the work of art. As the city enters contemporary touristic markets, does it keep its “aura of uniqueness”, or is otherwise levelled by a commercial logic which attempts to commodify everything in its wake? Benjamin (1992: 77; 84-86) defined “aura” as subject to the single occurrence of the work of art, holding a sort of cult value, the “here and now” of its creation; being technically reproduced, contended Benjamin (1992: 79; 84-86), the same aura would increasingly fade, going from a single event to a mass occurrence, its value measured by newfound exposure and renewed rendezvous with more individuals. One does seem indeed unable to “copy and paste”, technically reproduce a city in its specific spatial uniqueness: the “aura” is thus treasured intact (Fortuna, 1999a: 57). Even so, we argued there were particular spaces that were being duplicated all around the world, not directly opposing “unique” or “aural” locales within the historical city, but being besides them and in their midst: “non-places” (Augé, 1994), like a mere automobile or touristic bus and, more strikingly, airports, chains of fast food restaurants, apparel shops, hotels, commercial brands known worldwide (Fortuna, 1999a: 58). In this sense, the city was perfectly reproducible, because parts of it could be found in endless other cities across the globe. Closely following Benjamin's (1992: 78; 83) thoughts on photography as well, we discerned that unique urban elements - like singular historical monuments of a given city - could be reproduced through imagery, thrusting them to heights which could not erstwhile be reached: films, photos, advertising, symbols, all subordinate to the technical, and now increasingly virtual, reproduction of a city's landscapes. The far-off observer, in this context, could now (pre)view the aural uniqueness, as a result conveying its supposed cult value to a more exposed form; in touristic terms, the local, previously reserved to the inhabitants, is thrown open to the global, to the throngs of visitors.

Justly, we argued that these “throngs of visitors”, namely the tourists, were the translators of the contention upstream. More than passive figurants in the grand stage of urban tourism, we tended to view tourists-in-tourism as living through great upheaval in their lives. Change based on distance from home, but also cultural, symbolic, experiential: they left their usual world – ordinary, marked by work and everyday pendulums, in a word structural – toward another one entirely unusual, out of the structure of daily life – extraordinary, most certainly in vacations, perhaps happy and cathartic (Urry, 2002: 10-11). The touristic experience was to be, then, an intermission in life, a moment of exception, a world upside down: in the transition of non-tourist forms of social life to another deeply touristic, one is relieved of its customary life in order to search for something different, often times overvaluing those circumstances and moments within (Fortuna, 1999a: 69). The collision of different time rhythms brings about an awkward uncertainty in the identity of the tourist, though: in a world apart, certain variables like class, work condition and ethnicity, for instance, are thrown out of balance, in favor of more ephemeral variables like a full-fledged leisure of body and mind, the experimentation of novelties, the imagination of being “out” of oneself. Solid identities are figuratively and creatively destroyed, giving birth to new, transient figments of personality (with corresponding attitudes and actions), more capable of wading through the chaotic social world of tourism (Fortuna, 1999b: 16-25).

Moreover, we defended tourists had ancillary capacities imbued in their gazes to delve into historical urban contexts. Imagination was the first of those, a quality which allowed them to eye distant times from their own present backgrounds. The “official” written history of urban places, monuments and famed people, perhaps overbuilt and with appended charms (Peixoto, 2003), could be challenged by their own perceptions of reality, by their study, ultimately ascribing personal significances to them which could differ from their official or original properties (Fortuna, 1999c: 30-32). Physical space, to this extent, interferes in the symbolic space of each social agent, and vice versa: the hypothetical rebellious nature of experiencing one place differently from what was planned for it, as glimpsed by Lefebvre (1991) and Foucault (1984), is fully underlined here. The second feature was photography. The tourist gaze is reaffirmed by photography, whereby the whole process of visiting someplace in tourism is underscored by the “canonical” ritual of taking pictures: a “routinized non-routine” (Urry, 2002: 11). In all likelihood, the tourist photographs: it proves the journey was made, that he or she was there (Sontag, 2012:17). By extensive use of the camera (or smartphone nowadays), the natural gaze runs the risk of being replaced by a photographic one, setting aside reality by turning the journey into a mere hoarding of photos. In all fairness, tourists may photograph because it is a go-to action in face of uncertainty, the unknown and the different (Sontag, 2012: 17; 85): it is easy to do so because they are facing a new reality with the littlest of times to grasp it – and memorize it (Sontag, 2012: 160). To that degree, the touristic picture commands the gaze, telling us where to look, where we should look, in a context where the tourism industry strives to glorify some urban locales to the detriment of others, and especially in an epoch when online viewings of the destination abound, having the potential to preordain the tourist gaze even before it angles the surroundings in loco.

2. Our methodological design and its connection to Porto

Looking to answer the questions raised in the preliminary lines of this article, and in regards to our research design, we adopted a methodological configuration which entailed both quantitative and qualitative approaches to the subject at hand. Through the lens of a mixed type of research, we tried to reach a compromise between both angles, hoping to gain a more panoramic outlook on reality (Bericat, 1998: 9-15). We started on a strong exploratory note, and went forward constantly shuttling between experience and ideas; as if we wanted not only to say but to testify that experience needed an object of theory, as well as theory needed an empirical counterweight (Guerra, 2006). The outcome was a frequent and enriching discussion between reality, the data acquired, and our analytical “touchstones”.

Throughout the year of 2015, we traced several researching steps in order to fulfill our purposes. Besides the library of social investigation about tourism, which we started reading and kept coming back to, we started our fieldwork by conducting several observations in the historical centre of Porto3 , hoping to grasp the relationship between foreign tourists and the urban space(s) they were visiting; as said earlier, eyesight will often serve as gateway for the rest of the human senses to be expressed, and with this in mind we tried to pinpoint an element of performance on behalf of the visiting tourists, to capture their bodies in motion across the great urban maze (Crang and Franklin, 2001: 12-14). Afterwards, we amassed, and in turn analyzed, a coherent body of touristic and nigh- touristic images from specialized websites and from the tourists themselves, named afterward in this article. With this fundamental step, we tried to determine the role of touristic photographs in the making of the foreign tourists' representations, namely the search of information about the destination; the sacralization of certain touristic places (Fortuna, 1999a: 53-60); or even the conversion of a city's inherent value into symbolic capital (Gagliardi, 2009: 260).

During this latest step, we also started fieldwork anew by going out and inquiring foreign tourists by survey4 . This technique allowed up to “stop” the tourists in their tracks, as it was as brief as the short stay most of them would be having in Porto through city break. Approaching tourists in their very visits and hustle and bustle can be troublesome, and the survey was the ideal way of quickly gleaning information from them and their worldviews. The historical centre of Porto was once again the preferred site of operations. We finalized by interviewing foreign tourists within a more restricted scope, digesting what was discovered in straightforward questions about the nature of city break travelling to, and in, Porto. Apart from one, more prolonged interview to a Portuguese emigrant of the city, who often returns as a tourist, all others were administered online through personal email, left behind as part of the survey, in a tentative way of reaching out some tourists after having returned home5 .

Hereupon, some subtle remarks are due about the author's relationship with the research subject, his city, Porto. The becoming of this research made us acutely aware that the scientific knowledge we produce is not entirely objective, in the strict sense that it may contain autobiographical vestiges (Santos, 2003: 50-55), as purported by segments of post-modern science. Although we agree about the contentious nature of this statement or belief, it is indisputable that the knowledge we may discover or author is inseparable of our own life experience: the subject of our research thus follows our own footsteps by other means, preceded by values, beliefs (Santos, 2003: 52) and - most boldly in our case - more than two decades of living in the studied city. We owe a bow of reverence to Porto for igniting within us the spark of curiosity: as we witnessed more and more strange faces, different accents and laughter around the usual pathways and squares, we came to the realization that tourism and its intricate phenomena were changing our city of old. From that initial outburst of clairvoyance this work was borne, before a single letter was brought to bear. How to deny the influence?

3. The budding relationship between Porto and tourism

In the mapping of the sociodemographic regularities of the surveyed foreign tourists in the historical centre of Porto, 82 of them during the month of August of 2015, we verified a prevalence of young people between the age of 18 and 30 years old, as many women as men; mostly travelling in pairs (romantic couples), with college education; at the time working but on vacation, arising from several European countries (with considerable French and Spanish presence) and some intercontinental ones. Most were staying three or less nights within the city's limits, in line with city break modes of travelling, but finding that temporality perfectly reasonable to visit a city like Porto, and probable a possible return, so far as air travel remained low cost. We suggested that a city's authenticity started with each and every tourist who set foot in it, and by the motives which permeate their visit: “History” and “local culture”, “sights and landscapes”, all moved ahead of “touristic advertising” and “spontaneous travelling” drawn forth by discounts or low travel fares. We viewed advertisement as more insidious than explicit; and even if the “Porto idea” had sprung through word of mouth (digitally too), that does not counteract an ulterior virtual research of the destination, anticipating and imagining its landscapes, nooks and corners by photography. One of the most regular dynamics was the pace of travelling demonstrated by the surveyed tourists within the space of a single year: three quarters added Porto to at least another visited destination, with two or three complementary destinations nearly becoming a fait accompli shortly after. They indeed travelled a lot, across dispersed latitudes; and in Porto's example, it was not surprising to confirm that this city break in particular extended its usefulness to neighboring regions, expanding a theoretically concise journey.

We also discovered that the distinction between one city and another is promoted by the relationship the visitor construes with each of them. An array of different ways to touristically relate oneself to a city is discernible; but eyesight, the innate as the one obtained by photographic lens, is the way which acquires dominance toward everything else. To touch, savor, tread, wander about patterned itineraries or routes off the beaten tracks, speaking or not to local denizens, taking photos: everything is filtered first and foremost by the sieve of the eye, providing the frame to fill in afterward. To eye existent photographs of the destination, the map, the guide's hand, the human panorama, then to act (and photograph). Perhaps here we can recognise the paradox of the inability of the surveyed tourists to relate with the local population, despite saying they greatly valued it as an authentic element of the city's culture: beyond linguistic barriers, the eye captures first, the photograph stores, and the journey is resumed. But even at this point contradictions work in favor of variation: the foreign visitor may want to know a little bit more of the habits and daily tempos of inhabitants, in a curious and unpretending fashion (“ the true life”, as the interviewed French tourist said); and these may want to devote themselves to that potential relationship, despite the always looming commercial exchange. The authentic of a city and the diverse options of embodying it by means of the tourist gaze. Borrowing the title of a poetic anthology of Ana Hatherly (2004), we sustained that the touristic relationship of the individual with the urban space is often settled by eye interfaces, planes of vision which expand and overlap with the remainder of the human senses and personal resourcefulness – for instance, taking pictures also entails a tactile, tangible bodily function.

This “resourcefulness”, we advanced, is tied to the imagination of each tourist, not just on site, but before the journey per se. The mind travels as well as the body, and the tourist gaze is startled right at home. We tried to build a corpus of images intrinsically connected to tourism, ones which plausible tourists would look at by searching about the destination at hand. We privileged three very graphical channels: “Visit Porto and North”, a conglomerate of public and private regional agencies representing tourism in the north of Portugal (Miranda, 2015); “European Consumers Choice”, an independent non-profit organisation based in Brussels, Belgium which evaluates consumer products – this institution provided a touristic guide of Porto on the Internet after having crowned the city as the best European destination through online voting in 2012, 2014 (Miranda, 2015) and again in 20176 ; and the tourists themselves, by staging a kind of ethnographic challenge which positively provoked some tourists to photograph the surroundings after having answered the survey.

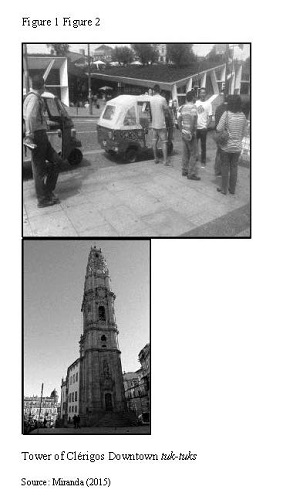

Needless to say, we don't have the confines in this article to fully and graphically translate what was done in this regard. Nevertheless, we adopted a strategy oft-used in the making of touristic guides to analyze the extracted body of images and photographs (Gorp, 2012): by symbolically transforming one place, which isn't touristic by default, into another place, now touristic and denoting a nuanced representation of reality amongst many possible others, these images hold an important role within the tourism apparatus throughout the world. Images derived from the first two aforementioned channels marked the presence of some typical strategies used to transfigure a place into “another”. The first one was petrification, throwing a place to “another time” by extolling its historical monuments and glorious past (Gorp, 2012) - in Porto's case, the frequency of images depicting the tower of Clérigos (of the clergy), São Bento's train station and the Port wine cellars was considerable7 . The second was virtualisation, the creation of ambiance in and around a physical place, trying to take the viewer there by imagining, and seeding the desire to travel to a destination in order to fulfill an experience which is meant to be but isn't quite so yet (Gorp, 2012) – in our research, we found a recurrent “human approach” to this kind of strategy (Barthes, 1997: 115), framing persons, much like the potential tourists, in their daily touristic activities, like sipping a glass of Port besides the Douro river (the watercourse which bathes Porto, flowing toward its end here, in the Atlantic ocean). Akin to this strategy is the unavoidable backdrop of stereotyped landscapes with which distinction is attained, in regards to the tourists' country of origin; through simplified and enhanced imagery of places and geography, ones which the eye can quickly glimpse and be enraptured, “another” physical locale is created, reaching out an invitation to whomever is checking (Gorp, 2012). In Porto, the Douro river is ever present, both riverbanks captured at all times of the day to fuel expectations of a daylong adventure.

The last channel mentioned above was special to us, as it was borne out of our own doubts and quandaries considerably late in the research. We wanted to involve the surveyed tourists by setting their gazes to work in situ, right after answering our scientific plight; apart from industry photographs, we thought we would've liked to see how they were taking their own photos whilst visiting the city: an “ethnographic challenge” was thus presented to them. The results were interesting, as no statistical analysis could be inferred from them; on the other hand, we discerned the diverging angles the tourist gaze could pivot: conforming, oriented toward what they had seen before in advertising, or what stood as a “mandatory” target for the camera, like a surrounding monument or church; and nonconforming, defiant in the sense the camera targeted less defining, more prosaic, elements of the same context, like a touristic tuk tuk (a sort of auto rickshaw which carries people around the city) and the encircling people, instead of the actual tower of Clérigos just beside8 . We stressed the ambiguous tourist gaze derived from this research step, the double significance that same physical place could elicit on the foreign tourists' representations of visited destinations.

In pursuit of this theme, we asked ourselves what Porto had to offer of most “unique” to the visiting, eye-first tourist (notwithstanding the virulence of this trait, since we reasserted the eye was like a spillway for the rest of the human senses); and its historical and monumental heritage came as a reply, those exemplary urban tracts declared as World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1996. We found a correlation between Porto being more authentic because of that specific “official and global” lining, despite having concluded the matter was exceedingly difficult to formalize. The aura of the typical and historical buildings and squares of Porto, taken from the “aural work of art” of Benjamin (1992) remained foggy: it was obvious that the tourists' attention would always be directed toward those urban elements, in turn finally deciding they were “unique” to anything else. The urban maze can't be duplicated building by building, street by street, tile by tile, despite its images and photographs (a sort of iconography of reality) freely flowing about touristic, imaginary and media channels. We went the other way around, heading toward the antithesis of the unique work of art: the reproduction of what surrounds the aural/authentic urban examples of Porto - places easily transposed from city to city - like chains of fast food restaurants (a McDonalds, for instance), transnational clothing and apparel stores, hotel networks, services, touristic buses, tuk tuks. Essentially, simple places tourists would find at home or in other near or distant urban destinations. We arrived at the conclusion that these non- typical elements tarnish the aura (or authenticity) of a city like Porto, trivializing it to some degree and making it increasingly kindred to other cities perfectly embedded in touristic circuits. At the same time, a double consciousness is manifest among foreign tourists to Porto: walking abreast and within the same city, the unique in the more local elements, and the commonplace in the more global ones.

Taken in this background, city break displays uncanny traits. We suggested this type of travel would disenchant the city in favor of the journey itself, as it opened up more frequent and diverse travel during a shorter span of time. This assertion dwindled as we took in our data, not because the surveyed tourists travelled much (they indeed did) but because the choice of city still mattered, overcoming the unbound desire of travelling to “new” and “undiscovered” destinations (the so-called pleasure of travelling, along with the novelty it entails), whichever they may be. The few interviews we conducted reassured the solemnity of choosing a particular urban destination, over the obstinacy of the new and quick-fire trips. Each city, then, appears to be unique, one before the others, despite demanding more analytical criteria to truly know their “aura”. With which hues should we have painted our first questioning? Was Porto or not a unique city to the tourist(s) gaze(s)? We believed it was, but quickly dispelling a supposed “universal quality” of its uniqueness; in other words, it may not have been Porto emanating that aura or authenticity, but the tourist itself, during its many-faced relationship with the visited space. Instead of being solely imbued within its concept of city, Porto's aura spread out, built by all those that traversed and experienced the city (and keep doing so); just like, perhaps, not being a “unique” and common aura, potentially similar to all, but a fragmented one, in accord with the intents and innermost feelings of each social agent, inhabitant or tourist alike.

In this measure, we alluded to the “builders of the city”, in loose translation of Lopes' expression (2002: 71-72), insofar as each social agent upheld an imagined (and imaginary) city, ever exposed to the slopes of objective and daily reality and to the breadth of its own possibilities. We believed it was through the dialogue between the represented city and the encountered city that the social agent could perceive its significance and therefore its aura. During the ethnographic challenge we posed to the foreign tourists, we saw how their gazes contrasted: the charm and allure of the historical building or enticing landscape were interspersed by a tree, a sitting person, less known statues laughing about one another. Both ways the nurture of a specific aura: more imagined than actual, and other times more real than imagined – the accepted and “official” meaning of a given space versus the intimate significance bestowed upon that space by each individual. Or, pursuing a literary vein, “the invisible cities” within any city, as written by Calvino (2015), being carried about by social agents: Zirma (2015: 28), wherefrom each traveller returns with different memories; Tamara (2015: 22-23), city of signs which tell us everything we should think, where every page has been already written; or Fedora (2015: 16) and Isidora (2015: 41-42), where places we have dreamt for ourselves are confronted with reality, turning dreams impossible, only presumed.

We advanced each tourist would take a different keepsake, an aura represented as only theirs, even though confined by the singularity of the journey, by the knowledge of the city (foregoing and elapsed), by negative accidents or emotive incidents, by their own perceptions of reality, all shaped by their specific and objective life conditions in travel and back home. We thought Porto's aura would be defined like this as observed by the tourist gaze, just as a kind of sentimental geography of a life spent there would be for the local dweller. “One Porto in each” maybe is too romantic and post-modern, and it is through the difficult and frustrating dialectic with the “Porto of everyone” that each one may build its city. Numberless and renowned examples could be purveyed, multiple cities of Porto that have been built over the bumped streets of living reality: the historical Porto, which may never return, spoken by local famed journalists and historians as Germano Silva - “Porto: Histórias e Memórias” (2011)9 - and Helder Pacheco - “Porto: Da Cidade e da Gente” (2003)10 ; the magical Porto as written through the pen of poets like Manuel António Pina - “Porto, Modo de Dizer” (2002)11 ; the sorrowful and romantic Porto as celebrated by Camilo Castelo Branco on his novel “ Amor de Perdição” (2006), first published in 1861; the sardonic Porto of Ramalho Ortigão and Eça de Queiroz, in a series of satirical chronicles about the Portuguese society of the nineteenth century published by both between 1871 and 1872, and by the former alone until 1882, titled “ As Farpas” (2013); the bourgeois city of old, pointedly characterized by a commercial class of English businessmen who had come to Porto and made their lives there, written by Júlio Dinis in “ Uma Família Inglesa” (2010), firstly issued in 1868; and finally, the city of each one's human and social experience, the home-work pendulums (overlooking what is around) or the gardens of infinite jaunts, the culture and sports, the one pertaining to the tourists, the one arising from the foggy river mouth.

We could have tapped Porto's surface further, as far as tourism is concerned: adding the practical level of maps and guides to the analysis, not just delving into the performance of using a map or into the imagination touristic photographs can induce, for instance. Or even a bolder, more constructive approach to the tourist itself and corresponding population-in-motion, in the same ilk of the ethnographic challenge: a bigger focus on interviews, perhaps “touristic life stories”, sociological portraits, since tourism, and the ensuing imagination, is increasingly integrated within the leisure practices of contemporary societies. And what about the other side, pertaining to Porto's citizens and residents? What significance do they grant to city break's intensified type of tourism in “their own city”? Which pros and cons? Do they really view tourists as a massive horde of invaders, conscripted to perpetual commercial exchange, with no added emotional and human value? How do they internalize erstwhile “free” spaces now subject to entrance fee - like Lello's famed and centennial bookshop12 – due to touristic influx? Here, we imagined Michel de Certeau (1980) and the great divide between dominant and popular cultures, and the actions or shapes each would undertake when facing the other: the “occupation armies” of the first type of culture toward the second; and the “guerrilla armies” of the second type fighting the first. Tourists as part of an “occupation army” in native lands? Grounded and objective research conditions can also hinder whatever invisible imaginaries the researcher may cling to.

What about Porto? Will it always be a fashionable city with regard to international tourism? According to Benjamin (2001: 72), merchandise embodies an autophagic rite, destined to be replaced by another commodity in due time. Within the scope of the fray between “commodified” cities in the cultural arena of global tourism - on the threshold of sociology of fashion and consumption – here's another possible road to be taken, which could be combined with the making of “mythical” cities, in loose adaptation of Barthes's myth concept (Barthes, 1997: 190), whereby cities have numberless significant (signs) and shapes (like the photographic picture) at their disposal to unceasingly redress themselves before the eyes of those who are most interested in tourism – here, semiotics. At the very end, Porto seems firmly embroiled in tourism, on the receiving end of international influxes all year long. Tourism is no longer a scant, occasional phenomenon in this city: the stability and discretion of contemporary urban tourism, with city break at the forefront, turned it into a permanent fixture of international travel. Despite the boundaries, as outright as hidden, that underlaid our research and scientific labor, we strained to write yet another page of this city's book, the same one which is filled daily by its inhabitants and tourists equally – we hope to have achieved this goal.

References

AUGÉ, Marc (1994), Não-Lugares: Introdução a uma antropologia da sobremodernidade, Venda Nova, Bertrand Editora. [ Links ]

AZEVEDO, Natália (2007), Políticas culturais, turismo e desenvolvimento local na Área Metropolitana do Porto – um estudo de caso , Tese de doutoramento em Sociologia, Porto, Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto. [ Links ]

BARTHES, Roland (1997), Mitologias, Lisboa, Edições 70. [ Links ]

BAUMAN, Zygmunt (1996), “From Pilgrim to Tourist – or a Short History of Identity”, in Stuart Hall; Paul Gay (orgs.), Questions of Cultural Identity, London, Sage Publications, pp. 18-36.

BENJAMIN, Walter (1992), “A Obra de Arte na Era da sua Reprodutibilidade Técnica”, in Walter Benjamin, Sobre Arte, Técnica, Linguagem e Política, Lisboa, Relógio d'Água, pp. 71-113.

- (2001), “Paris, capital do século XIX”, in Carlos Fortuna (org.), Cidade, Cultura e Globalização: ensaios de sociologia, Oeiras, Celta Editora, pp. 67-81.

BERICAT, Eduardo (1998), La integración de los métodos cuantitativo y cualitativo en la investigación social: significado y medida, Barcelona, Ariel. [ Links ]

BOORSTIN, Daniel (1992), The image: a guide to pseudo-events in America, New York, Vintage Books. [ Links ]

BRANCO, Camilo Castelo (2006), Amor de Perdição, Alfragide, Dom Quixote. [ Links ]

CALVINO, Italo (2015), As Cidades Invisíveis, Alfragide, Dom Quixote. [ Links ]

CERTEAU, Michel de (1980), L?invention du quotidien. Vol. 1, Acts de faire, Paris, Union Génerale d?Éditions. [ Links ]

CHOAY, Françoise (1999), A alegoria do património, Lisboa, Edições 70. [ Links ]

CRANG, Mike; FRANKLIN, Adrian (2001), “The trouble with tourism and travel theory?”, Tourist Studies, vol. 1 (1), pp. 5-22.

CUNHA, Licínio (2010), “Desenvolvimento do Turismo em Portugal: os Primórdios”, Fluxos & Riscos, vol. I, pp. 127-149.

DINIS, Júlio (2010), Uma Família Inglesa, Porto, Porto Editora. [ Links ]

DUNNE, Gerard; FLANAGAN, Sheila; BUCKLEY, Joan (2010), “Towards an Understanding of International City Break Travel”, International Journal of Tourism Research, vol. 12 (5), pp. 409-417.

FERREIRA, Alvaro; RUA, João; MARAFON, Glaucio José; SILVA, Augusto César (orgs.) (2013), Metropolização do espaço: gestão territorial e relações urbano-rurais , Rio de Janeiro, Consequência. [ Links ]

FORTUNA, Carlos (1999a), “Turismo, autenticidade e cultura urbana”, in Carlos Fortuna, Identidades, Percursos, Paisagens Culturais: Estudos Sociológicos de Cultura Urbana, Oeiras, Celta Editora, pp. 47-71.

- (1999b),” Nem Cila nem Caribdis: somos todos translocais”, in Carlos Fortuna, Identidades, Percursos, Paisagens Culturais: Estudos Sociológicos de Cultura Urbana, Oeiras, Celta Editora, pp. 11-21.

- (1999c), “As cidades e as identidades: narrativas, patrimónios e memórias”, in Carlos Fortuna, Identidades, Percursos, Paisagens Culturais: Estudos Sociológicos de Cultura Urbana, Oeiras, Celta Editora, pp. 23-44.

FORTUNA, Carlos (org.) (2001), Cidade, cultura e globalização: ensaios de sociologia, Oeiras, Celta Editores. [ Links ]

FORTUNA, Carlos; LEITE, Rogerio (orgs.) (2009), Plural de cidade: novos léxicos urbanos, Coimbra, Almedina. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel (1984), “Des Espaces Autres”, Architecture/Mouvement/Continuité, vol. 5, pp. 46-49.

FUNDAÇÃO FRANCISCO MANUEL DOS SANTOS (2015), Três décadas de Portugal europeu: balanço e perspetivas, [Accessed in 15.11.2017]. Retrieved at https://www.ffms.pt/upload/docs/PortEuroUmBal3Dec.pdf [ Links ]

GAGLIARDI, Clarissa (2009), “Turismo e Cidade”, in Carlos Fortuna; Rogerio Leite (orgs.), Plural de cidade: novos léxicos urbanos, Coimbra, Almedina, pp. 245-263.

GORP, Bouke van (2012), “Guidebooks and the Representation of “Other” Places”, in Murat Kasimoglu; Handan Aydin (orgs.), Strategies for Tourism Industry – Micro and Macro Perspetives, Rijeka, Croatia, InTech, pp. 3-32.

GUERRA, Isabel (2006), Pesquisa qualitativa e análise de conteúdo: sentidos e formas de uso , Cascais, Principia. [ Links ]

HATHERLY, Ana (2004), Interfaces do olhar – uma antologia crítica; uma antologia poética, Lisboa, Roma Editora. [ Links ]

LASH, Scott; URRY, John (1998), Economías de signos y espacio: sobre el capitalismo de la posorganización, Buenos Aires, Amorrortu Editores. [ Links ]

LEFEBVRE, Henri (1991), The production of space, Oxford, Blackwell. [ Links ]

LOPES, João Teixeira (2002), Novas Questões de Sociologia Urbana: conteúdos e «orientações» pedagógicas, Porto, Edições Afrontamento. [ Links ]

MACCANNELL, Dean (1999), The tourist: a new theory of the leisure class, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, University of California Press. [ Links ]

MIRANDA, Tiago (2015), O Porto turístico: olhares sobre a cidade, Tese de mestrado em Sociologia, Porto, Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, Fernando (2008), O Turismo e os museus nas estratégias e nas práticas de desenvolvimento territorial , Tese de doutoramento em Museologia, Lisboa, Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias. [ Links ]

ORTIGÃO, Ramalho; QUEIROZ, Eça de (2013), As Farpas, Parede, Principia. [ Links ]

PACHECO, Helder (1994), Porto – Memória e Esquecimento, Porto, Edições Afrontamento. [ Links ]

- (2001), Porto: Lugares dentro de nós, Porto, Edições Afrontamento. [ Links ]

- (2003), Porto: Da Cidade e da Gente, Porto, Edições Afrontamento. [ Links ]

PEIXOTO, Paulo (2003), “Centros históricos e sustentabilidade cultural das cidades”, Sociologia, Revista da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, vol. 13, pp. 211-226.

PINA, Manuel António (1994), O Anacronista, Porto, Edições Afrontamento. [ Links ]

- (2002), Porto, Modo de Dizer, Vila Nova de Gaia, Edições Asa. [ Links ]

PINA, Manuel António (2014), Crónica, Saudade da Literatura, Lisboa, Assírio & Alvim. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Boaventura de Sousa (2003), Um Discurso sobre as Ciências, Porto, Afrontamento. [ Links ]

SILVA, Augusto Santos (2007), “Como abordar as políticas culturais autárquicas? – uma hipótese de roteiro”, Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas, vol. 54, pp 11-33.

- (2011), Porto: História e Memórias, Porto, Porto Editora. [ Links ]

- (2013), Porto: Nos Lugares da História, Porto, Porto Editora. [ Links ]

- (2015), Porto: Viagem ao Passado, Porto, Porto Editora. [ Links ]

SONTAG, Susan (2012), Ensaios sobre Fotografia, Lisboa, Quetzal Editores. [ Links ]

URRY, John (2002), The Tourist Gaze, 2nd Edition, London, Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Other references

Câmara Municipal do Porto, [Accessed in 26.07.2018]. Retrieved at http://www.cm-porto.pt/

Clérigos Tower, authorship of Visit Porto., [Accessed in 26.07.2018]. Retrieved at http://www.visitporto.travel/Visitar/Paginas/Descobrir/DetalhesPOI.aspx?POI=1407&AreaType=1&Area=8

Historic Centre of Oporto, Luiz I Bridge and Monastery of Serra do Pilar, authorship of UNESCO [Accessed in 18.11.2017]. Retrieved at http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/755 .

Sandeman Cellars, authorship of Visit Porto., [Accessed in 26.07.2018]. Retrieved at http://www.visitporto.travel/Visitar/Paginas/Descobrir/DetalhesPOI.aspx?POI=383&AreaType=1&Area=8

São Bento Railway Station, authorship of Visit Porto., [Accessed in 26.07.2018]. Retrieved at http://www.visitporto.travel/Visitar/Paginas/Descobrir/DetalhesPOI.aspx?POI=1805&AreaType=1&Area=8

The World's Most Beautiful Bookshop, authorship of Livraria Lello Porto, [Accessed in 26.07.2018]. Retrieved at https://www.livrarialello.pt/en-us/livrarialello-institucional

Touristic guide of Porto, authorship of the European Consumers Choice, [Accessed in 18.11.2017]. Retrieved at https://www.europeanbestdestinations.com/travel-guide/porto

Endereço de correspondência Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, Via Panorâmica, s/n, 4150-564 Porto, Portugal. Email: tiago_miguel_ribeiro@hotmail.com

Artigo recebido em 12 de janeiro de 2018. Publicação aprovada em 25 de julho de 2018.

Notas

1 As seen in UNESCO's World Heritage list within its official website, referenced below.

2 The brand “Porto.” has revolutionized the graphic image Porto and its inhabitants have of themselves. Designed in 2014, and constantly iterated upon ever since, its visual principles outline every dimension of the local government's actions, as can be seen in the corresponding official website, referenced below.

3 We carried out 5 unstructured, free-flowing observations during the first phase; and another 5, more structured ones, in a second phase, trying to ascertain the key elements of the foreign tourists' relationship with the visited city – and all of them between March and April of 2015.

4 We surveyed 82 foreign tourists during the month of August of 2015, greatly taking advantage of their moments of respite in the gardens and shades of Porto's urban landscape.

5 The first interview was an open-ended, unstructured glimpse to the thoughts of a Portuguese emigrant of the city, who was 56 years old at that moment (April of 2015): truck driver, male and married, living in Switzerland for more than 30 years, with a level of education lower than high/grammar school (unspecified, though). The second set of interviews (3 in total) was conducted in September of 2015, in a semi-structured fashion: the first referred to an unmarried Spanish male, who was 31 years old and worked as slater/tiler, having secondary education; the second was made to a divorced Swiss female, who was 30 years old and worked as a social educator, having a bachelor's degree (the only interviewee who had visited Porto before this occurrence); and the third was done to a married French woman, who was 57 years old and worked as a computer engineer, having a master's degree.

6 As seen in the European Best Destinations official website, a recent branch of the European Consumers Choice organization related to European travel, referenced below.

7 As seen next page in figure 1, for example. These three locales are trademarks of Porto's touristic portfolio, referenced below: the first, perhaps the most significant building in the city of Porto, dating back to the eighteenth century; the second, a railway station built at the dawn of the twentieth century, on the site of an ancient convent, whose interior is furnished with a collection of tiles depicting both transport and Portuguese history; and the third, the cellars where Port wine is stored, not in the city proper, but in the neighbor city across the Douro river, Vila Nova de Gaia.

8 As seen in figure 2.

9 Germano Silva, a man of multiple crafts in his life, notably journalism, has published several more accounts of Porto's history, such as “Porto: Nos Lugares da História” (2013) and “Porto: Viagem ao Passado” (2015).

10 Helder Pacheco, a teacher by calling, and lifetime researcher of Porto's social and cultural forms, has been at the forefront of the city's written historiography, including titles like “Porto – Memória e Esquecimento” (1994) and “Porto: Lugares dentro de nós” (2001).

11 The late Manuel António Pina, on the other hand, was a writer and poet throughout his life, and adopted Porto as his city, having been born elsewhere in Portugal, in the district of Guarda. His works range from poetry to children's literature, and his thoughts about the city of Porto can be more readily found in the journalistic pieces he authored while working at a local newspaper, namely “Crónica, Saudade da Literatura” (2014), and “O Anacronista” (1994).

12 “Lello & Irmão” is a bookstore located within the scope of Porto's historical center, inaugurated in 1906. Famous for its architecture - façade and interior alike - it has become a mainstay of the city's touristic postcard (and attendant routes), gaining international prominence in the meantime: it has been oft named one of the most beautiful bookstores in the world, as can be seen on their official website, referenced below. The aforementioned “entrance fee” is redeemable by purchasing a book there, and it was instituted to minimize the newfound pressure the place has been subject to by its increasing visitors.