INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are one of the leading causes of death globally and it is estimated that CVDs were responsible for 17.9 million deaths in 2016 (31% of all global deaths). AMI and stroke account for 85% of all CVD deaths.1,2 In 2017, among Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) members, diseases of the circulatory system accounted for 31% of all deaths.3 In Europe, in 2015, ischemic heart diseases represented 18% of preventable mortality and 32% of amenable mortality.4 In Portugal, CVDs are also the leading cause of death, representing 29.4% of all deaths in 2017. Ischemic cardiac disease and AMI account for 6.6% (7314 deaths) and 4.1% (4542 deaths) of all deaths, respectively.5 In 2018, 32 732 (29.0%) deaths related to CVDs were registered.6,7

Acute chest pain (ACP) is the perception of non-traumatic pain or a thoracic discomfort localized anteriorly (between the base of the nose and the umbilicus) and/or posteriorly (between the occiput and the 12th vertebra).8 A variety of disorders could cause ACP, ranging from life-threatening syndromes (e.g., acute coronary syndromes, acute aortic syndrome, and pulmonary embolism) to mild conditions (e.g., costochondri-tis, gastroesophageal reflux, peptic ulcer disease, and psychogenic).9-13

The triage of patients with ACP in the emergency depart-ment (ED) is challenging and the first goal is to identify and manage a life-threatening condition such as AMI. A careful clinical history, physical examination, 12-lead ECG recording and interpretation within 10 minutes of first medical contact (FMC), measurement of cardiac troponin, and a thoracic radiography are fundamental to guide the diagnosis and to differentiate a cardiac-related ACP from a non-cardiac ori-gin. The priority in patients with AMI is to identify the ones who need to be transferred to a hemodynamic laboratory to undertake an immediate percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).8-13

In Portugal, in 2007, in order to improve the time inter-val between symptom onset and effective treatment (e.g., angioplasty), a coronary fast-track system called “Via Verde Coronária” has been implemented to provide a rapid and ef-ficient transport from the pre-hospital setting or a hospital without the necessary facilities to a hospital able to perform primary angioplasty. This program is coordinated by the national institute of medical emergency (Instituto Nacional de Emergência Médica - INEM) in collaboration with other national entities. This fast-track approach contributes to the reduction of mortality rates and to an improvement in patients’ prognosis.14,15However, a large number of patients with AMI-related symptoms do not call the emergency number and go directly to the hospital by their own means, which have led to the need to implement an in-hospital VVC. Each hospital created its own protocol, which may perform differently and may have different results in terms of main diagnosis, the prevalence of cardiac-related causes, the time interval be-tween FMC and the onset of VVC-related symptoms (e.g., oppressive precordial pain, sweating, nausea and/or epigas-tric pain at the triage).16 However, to the authors’ best knowledge, data on the performance of in-hospital VVCs are still scarce in the literature.

Therefore, the aims of this study were to characterize the main diagnoses detected in patients included in VVC and to evaluate the proportion of cases diagnosed with AMI among this sample.

Material and Methods

STUDY DESIGN AND SETTING

A retrospective observational study was undertaken in the emergency department (ED) of a hospital from Alentejo between 01/06/2017 and 31/05/2018. The hospital covers a resident population of about 126 692 inhabitants, with an area of influence of 8542.7 km2, which corresponds to ap-proximately 9.3% of the national territory.

In this hospital, during triage, VVC is activated when the patient presents an oppressive precordial pain that may irradi-ate to the left arm or neck, and may be associated with sweat-ing, nausea, and/or epigastric pain. The internal medicine physician is then called and an ECG is performed in the first 10 minutes after patient admission. According to the clinical evaluation, ECG result and sometimes laboratory results, phy-sicians choose the appropriate strategy for the patient (e.g., patient can be transferred to another hospital, or to another department).

POPULATION AND SAMPLE

The theoretical population was defined as the resident population covered by this hospital, which was 116 557 in-habitants in 2018. Patients were included if they were aged 18 or older, and presented any related-VVC symptoms, as above described. Patients were excluded if they presented chest pain that did not match such criteria.

Considering a population of 116 557 inhabitants, a mean prevalence of chest pain at admission in the ED of 3.5%,17-20a beta error of 3% and a 95% confidence interval, a theoretical sample of 144 patients was estimated.

OUTCOME DEFINITIONS AND MEASURES

The primary endpoints were defined as: a) the main diagnoses extracted from patients where VVC was activated, using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM)21; and b) the propor-tion of AMI calculated as the following formula: Prevalence of AMI = Number of patients with AMI/Total sample.

The secondary endpoints were defined as possible differences between patients with AMI vs non-AMI in terms of duration of pain (hours between the beginning of chest pain and the ED admission), and the number of cardiovascular risk factors (essential arterial hypertension, dyslipidaemia, previous cardiac disease, smoking (active and ex-smoker), type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, chronic kidney disease). The same differences were evaluated in patients with different types of AMI (ST-segment elevation myocardial in-farction - STEMI vs non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction - NSTEMI).

DATA EXTRACTION

Data were extracted from medical charts since admission at the ED until being transferred to another department (e.g., cardiology department, and internal medicine department) or eventually being discharged from ED. At admission variables such as sociodemographic (e.g., age and sex) and clinical variables (e.g., cardiovascular risk factors, troponin levels, duration of chest pain, and Killip-Kimball classification22,23) were extracted. Cardiovascular risk factors were characterized and extracted based on the electronic health register. During their stay in the ED, data on ECG and troponin levels were also ex-tracted. Main diagnosis was coded at the end of emergency episode using ICD-9CM.21

Initially, the sample was divided into two groups: cardiac and non-cardiac events. The cardiac group was then sub-di-vided into two levels: AMI and non-AMI. Finally, the AMI group was divided into two levels: STEMI and NSTEMI.

ETHICS AND CONFIDENTIALITY

This study was approved by the Ethics Commit-tee of the hospital where data was collected (document EDOC/2020/18845).

DATA ANALYSIS

Data analysis was performed using uni- and bivariate sta-tistics (IBM SPSS v.27.0). Sociodemographic and clinical characterization was performed using descriptive statistics, where numerical variables were expressed using central tendency and dispersion (e.g., mean and standard deviation - SD) mea-sures and categorical variables as absolute and relative frequencies. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov was used to assess if the sample followed a normal distribution. Comparisons between patients with AMI vs non-AMI and between STEMI vs NSTEMI were made using chi-square test and t-student test, for a statistical significance of less than 0.05.

Results

SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC AND CLINICAL CHARACTERIS-TICS

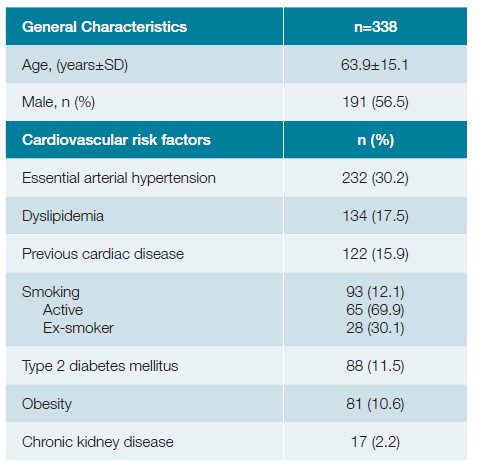

A total of 338 patients were included, where 56.5% (n = 191) were male with a mean age of 63.9 ± 15.1 {19;96} years old. Essential arterial hypertension (30.2%; n = 232), dyslipidaemia (17.5%; n = 134) and previous cardiac disease (15.9%; n = 122) were the most frequently cardiovascular risk factors identified among this sample (Table 1).

MAIN DIAGNOSES FOUND WHEN VVC WAS ACTIVATED

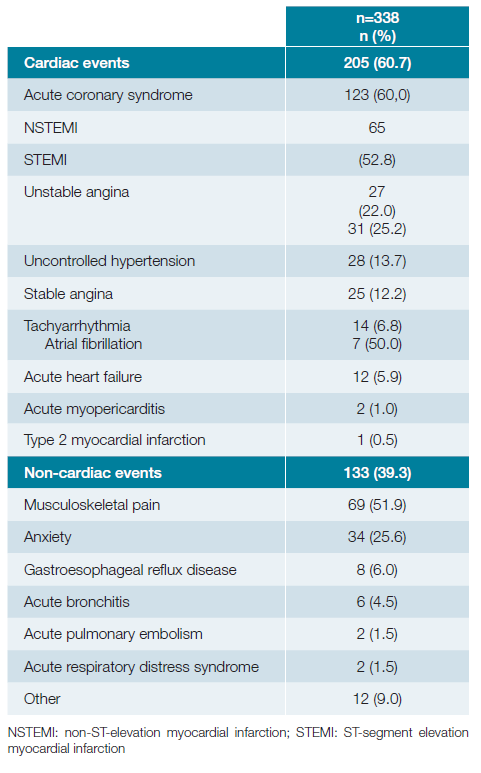

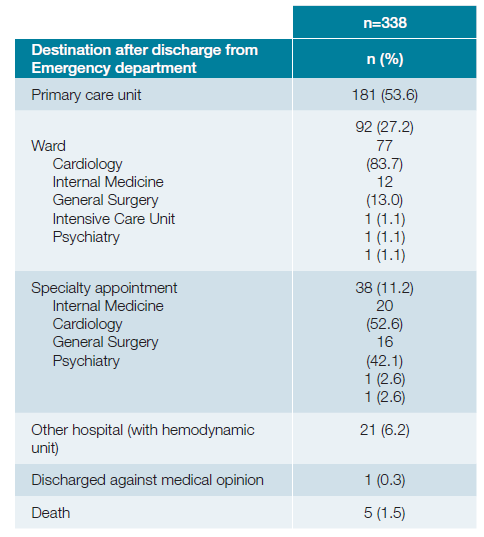

Most diagnoses were from the circulatory system (61.2%; n = 207), followed by musculoskeletal (20.4%; n = 69), men-tal and behavioural disorders (10.4%; n = 35), and other systems (8.0%; n = 27). Musculoskeletal pain (51.9%; n = 69) and anxiety (25.6%; n = 34) were the most frequent non-cardiac causes identified. Uncontrolled hypertension (13.7%; n = 28) and stable angina (12.2%; n = 25) were the leading cardiac causes apart from acute coronary syndrome which accounted for 60.0% (n = 123) (NSTEMI: 52.8%; n = 65 | STEMI: 22.0%; n = 27 | unstable angina: 25.2%; n = 31) of the cardiac causes (Table 2). At the end of the emergency episode, half of the patients (53.6%; n = 181) were transferred to a primary care unit and 27.2% (n = 92) were admitted to other departments (Table 3).

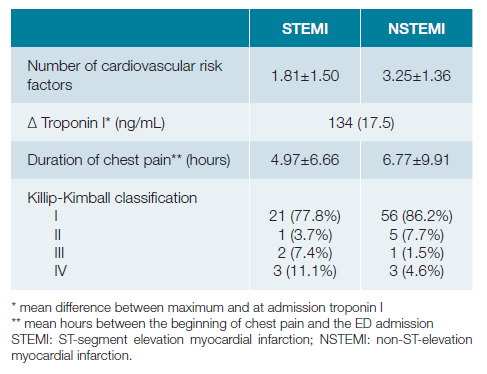

PROPORTION OF AMI AMONG PATIENTS FROM VVC

AMI was present in 27.2% (n = 92/338) of the sample. In the AMI group, the mean difference between the maximum-level of troponin I and the value at admission was 15.11 ± 23.18 ng/mL. According to the Killip-Kimball classification, the majority of NSTEMI (86.2%, n = 56) and STEMI (77.8%, n = 21) was class I. Four of the six patients with class IV have died (NSTEMI: n = 2; STEMI: n = 2) (Table 4).

There were differences when comparing the number of risk factors between patients with AMI and non-AMI (2.83 ± 1.54 vs 2.06 ± 1.49 risk factors per patient, respectively; p < 0.001). Similar findings were identified when comparing patients with NSTEMI and STEMI (3.25 ± 1.36 vs 1.81 ± 1.50 risk factors per patient, respectively; p < 0.001). There was a statistically significant difference between the duration of pain in AMI and non-AMI patients (6.24 ± 9.08 vs 10.53 ± 18.23 hours of pain, respectively; p = 0.032), whereas no difference in pain duration was found when comparing patients with NSTEMI and STEMI (6.77 ± 9.91 vs 4.97±6.66 hours of pain, respectively; p = 0.390).

Discussion

This study showed that most diagnoses found in this spe-cific VVC approach were from the circulatory system, followed by musculoskeletal, and mental and behavioural disorders. The cardiac causes were more frequent than the non-cardiac ones. In the cardiac group, the acute coronary syndrome (ACS) was the major cause identified. Most of these patients presented a NSTEMI, followed by STEMI and unstable angina. Another Portuguese study, conducted in the ED of a tertiary hospital, showed that the most common final diagnosis in patients admitted with chest pain was unspecific chest pain (36.9%; n = 86), ACS (9.4%; n = 22), and anxiety-depressive disorder (9.0%; n = 21). In the ACS group, seven patients 32%) presented a NSTEMI, five presented (23%) a STEMI and ten patients (46%) presented unstable angina.18 These results are aligned with our findings. Differences found may be ex-plained by the fact that we only included patients where VVC was activated, instead of all patients presenting chest pain. This could be an indicator of the good performance of our in-hospital VVC protocol.

A study in a Swedish ED included 11 141 patients admitted with chest pain. From those, 834 (7.5%) presented an ACS, 1729 (15.5%) another cardiac cause (including stable angina), and 4203 (37.7%) presented unspecific chest pain.

About 23% of all patients presented a cardiac cause.24 A Spanish study reported that from the patients who have been discharged from the ED, after a chest pain episode, the most common diagnoses were atypical, mechanical, or noncoro-nary pain, costochondritis, contracture (59%; n = 750) followed by bronchial disease, catarrh, pneumonia (11.7%; n = 148), and anxiety-depression syndrome (5.5%; n = 70).19 A German study about the chief complaints in medical emergencies reported a total of 3954 patients admitted with chest pain, where 47.5% (n = 1879) were admitted as in-patients. From these, angina pectoris (34.3%; n = 645) and AMI (21.4%; n =402) were the most frequent diagnoses.25

In the Norwegian health system, generally all patients re-quired a referral from an on-call general practice or anoth-er physician for admission to the ED, with exception made for patients eligible for accelerated pathways (e.g., STEMI or stroke) or those transported directly from the scene of an event by emergency medical services. A study characterizing chest pain in the ED identified that more than one-third of patients (n = 903) had a cardiac cause and 12.2% (n = 291) of all patients had an ACS. Among this group, 170 (58.4%) patients had a NSTEMI, 46 (15.8%) a STEMI and 75 (25.8%) an unstable angina, similar to our study.26

Even though our study showed a higher percentage of cardiac-related ACP and ACS comparing to previous studies, according to the WHO Mortality Database, Portugal pres-ents a lower mortality rate due to coronary heart disease when compared to Norway and Sweden. This may be an indicator that despite differences in healthcare systems, this in-hospital approach alongside with the national emergency approach may be sensitive enough to detect a higher number of cases, leading to decreased mortality and better prognosis.27

Mental and behaviour disorders were also frequent causes of chest pain in Spanish and Portuguese studies.18,19Some studies have an important percentage of non-specific chest pain, in contrast to our study, where all etiologies of pain were identified.18,24,26

Our study showed that 27.2% of the sample admitted to VVC had an AMI diagnosis, higher than reported in previous studies.18,26This could be explained by differences in the health care systems and referral protocols in place and by the respective studies’ inclusion criteria. In our study, we have re-stricted inclusion to patients admitted to the in-hospital VVC and not all patients with chest pain. Nonetheless, we consider this could be a performance indicator suggesting good practice and high sensitivity of our in-hospital VVC protocol in identifying AMI patients.

Essential arterial hypertension and dyslipidemia were also the most frequent cardiovascular risk factors identified in three studies focusing on chest pain in ED.18,19,28

To the authors’ best knowledge, this is the first study presenting data from in-hospital VVC. Understanding the work-flows and procedures in place in our hospital’s VVC may help other hospitals to implement similar protocols, thus contributing to help the national health system maintaining data up-to-date. Additionally, our protocol showed a good performance in terms of identifying cardiac causes, including major cardiovascular events. However, AMI represented only a quarter of the sample, which may indicate that future work in improving this fast approach should be done to further increase the sensitivity.

This study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. The fact that the study was conducted in one single hospital is an a priori limitation, implying data obtained may not be generalized to other hospitals. The choice for a retrospective design also has inherent limitations, including potential information bias. Additionally, main diagnosis were coded at the end of the emergency episode, which did not allow the follow-up of the patients. Future studies resorting to prospec-tive designs are recommended to supplement the data here reported.

Conclusion

Our study showed that even though most of the diagno-ses obtained were from the circulatory system, only a quar-ter of all in-hospital VVC patients were diagnosed with AMI. This finding suggests that the chest pain symptom may not be sensitive enough as a single triage factor for the inclusion of patients in VVC at admission.