Introduction

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), also known as Rendu-Osler-Weber disease, is a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by abnormal blood vessel genesis.1,2The diagnosis is established by the Curaçao Criteria based on clinical symptoms, identification of mucocutaneous telangiectasias, visceral involvement, and family his-tory.1-5Neurologic complications can arise from paradoxical embolism due to pulmonary arteriovenous malformations (PAVMS) and are potentially fatal.1,3,4,6-9Giving the low prevalence of HHT, these complications are often regarded as isolated events, enabling further complications.4,7We report a case of a patient that presented two of the most devastating complications of PAVMs. With this example, we expect to highlight the complexity of HHT and its complications, the importance of testing relatives, and above all that we should not only treat the presenting symptoms but also aim to prevent future complications.

Case Report

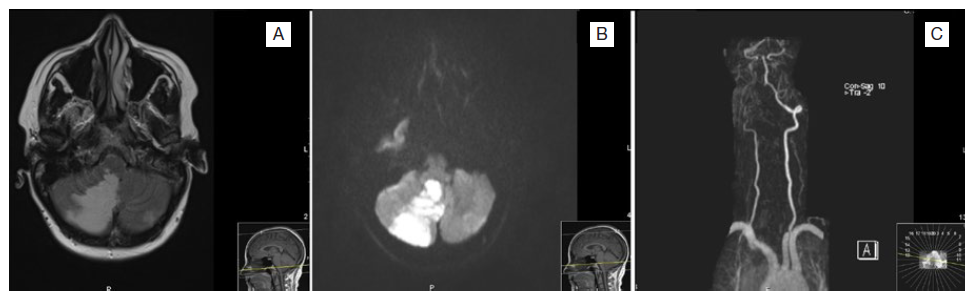

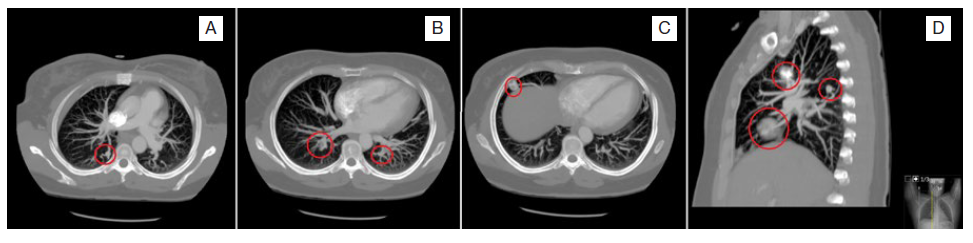

A 45-year-old female presented to the emergency department after a sudden onset of nausea, vomiting, vertigo, diplopia, and confusion. On examination, she had conjuga-ted gaze deviation and horizontal nystagmus to the right, paresis of the right hemiface, and right arm dysmetria. Her past medical history included previous episodes of epistaxis. She had no chronic medication other than an oral contraceptive. A brain computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a subacute infarction in the right posteroinferior cerebellar artery (PICA), including the bulbar branch, confirmed by a contrasted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 1). MRI allowed further identification of a dissection of the V3 segment of the right vertebral artery, with distal occlusion and retrograde flow through the contralateral vertebral artery, and hyperintense lesions on T2 and flair characteristics of non-recent ischemic lesions in the right parietal cortex, left thalamus, and cerebellum. Since she presented with more than twelve hours of symptoms, thrombectomy or fibrinolysis were not indicated, and the patient was admitted for etio-logic study. During the hospital stay she had an episode of desaturation which prompted the realization of a contrasted chest and abdomen CT that ultimately revealed a pulmonary embolism, multiple PAVMs, and hepatic telangiectasias (Fig. 2). The transesophageal echocardiogram with bubble study confirmed right-to-left passage of bubbles supporting the existence of a pulmonary arteriovenous shunt; a patent foramen ovale was excluded. These findings contributed to the diagnosis of Rendu-Osler-Weber disease. Following that, a detailed family history was obtained which revealed that a brother, a sister, and a niece had been previously diagnosed with Rendu-Osler-Weber disease, and that the remain siblings presented also repeated episodes of epistaxis and were under investigation. The patient was anticoagulated due to pulmonary embolism, initially with enoxaparin, and after that with warfarin. Sixteen days later, she was discharged home with only a slight decrease in right arm muscle strength and a discrete dysmetria.

Figure 1: Brain magnetic resonance imaging relative to the first hospitalization. Images A and B present a recent ischemic lesion in the medial portion of the right cortical and subcortical cerebellar hemisphere, with T2 prolonged and diffusion restriction, re-sidual involvement of the right restiform body is also admitted, corresponding to the recent stroke in the medial territory of in the right posteroinferior cerebellar artery. Image C shows the dissection of the V3 segment of the right vertebral artery with a distal occlusion.

Figure 2: Contrasted chest computed tomography revealing bilateral pulmonary embolism with luminal filling defects compatible with endoluminal thrombi (image C) and multiple pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, seen as serpiginous masses connected to the blood vessels (images A to D).

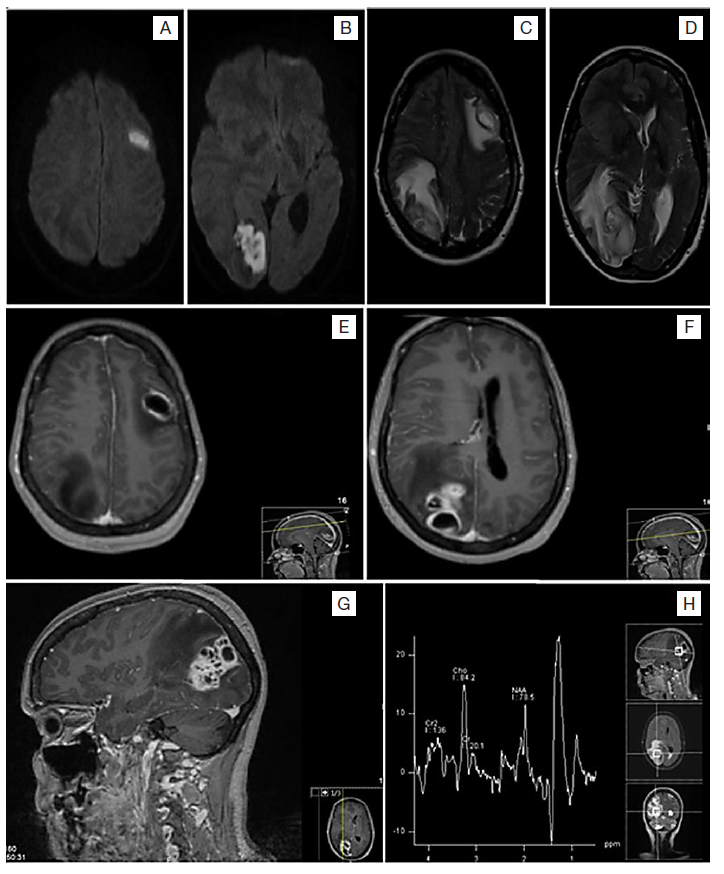

One year later, she sought medical attention because of weeks of complaints about severe headache, nausea, and vomiting. She additionally recalled having fever and chills in the previous week. In the emergency department she was lethargic and presented papilledema, left homonym hemianopsia, and motor deficits of the right arm and hand. Brain CT scan revealed two hypodense lesions - left frontal and right occipital - with surrounding edema; brain MRI (Fig. 3) described the lesions as abscesses with probable septic distribution given the vascular topographic distribution in peripheral territories of the middle and posterior cerebral arteries.

Figure 3: Brain magnetic resonance imaging relative to the second hospitalization. Images A to D show two expansive lesions left frontal and right occipital constituted by hyperintense cystic formations with a slightly hypointense capsule in T2; there is also a halo of vasogenic edema and consequent occipital ventricular deformation. Images E to G show a hyperintense capsule in T1; the cystic formations present diffusion restriction with peripheral gadolinium uptake, and without an increase in perfusion, they correspond to cerebral abscesses. Image H represents proton spectroscopy, which reveals lactates, lipids, and the apparent presence of amino acids (0.9 ppm), the later products of bacterial degradation.

The patient underwent stereotactic puncture and drainage of purulent material and initiated intravenous treatment with dexamethasone, phenytoin, metronidazole, ceftriaxone, and gentamicin. Cultures from blood and purulent brain material were negative. After a multidisciplinary discussion, the abscesses were assumed to be related to paradoxical embolism from the PAVMs. Twenty-two days later, she was discharged home without noticeable deficits.

She stayed under vigilance in Internal Medicine consultation and was scheduled for the embolization of the PAVMs. She underwent embolization of two arteriovenous malforma-tions in the inferior lobe and one in the medial lobe of the right lung; however, some were too large to arterial embolization, requiring a segmental pneumectomy. The histologic study after pneumectomy confirmed dilated and tortuous arterial vessels and dilated venous vessels reinforcing the diagnosis of PAVMs.

The genetic study confirmed HHT with a genetic variant on the endoglin (ENG) gene (c.777_778dup, p.Ser260Cysfs*100), not described in the literature, and shared with other family members.

As of today, the patient did not present any further com-plications and the neurological deficits resolved completely.

Discussion

HHT is an autosomal dominant disease, characterized by a familial pattern of telangiectasia and arteriovenous malformations.1 The diagnosis of this rare disease is made based on Curaçao clinical criteria.1-5Our patient presented four of the four criteria: epistaxis, mucosal telangiectasis, hepatic arteriovenous malformations, PAVMs and history of first degree relatives with the disease.

Although the relation between her complaints and this diagnosis may now seem easy to establish, the fact is that before presenting the first complication, she was unaware that she suffered from a family disease.

Regular nasal bleeding is an early marker of HHT and should raise suspicion for this condition in young patients wi-thout risk factors presenting with a stroke or cerebral abscess.1-5Neurologic symptoms are typically not the first sign but frequently complicate the disease due to paradoxical embolism from the PAVMs and cerebrovascular malformations.6-8Ischemic stroke and brain abscess can present as serious complications of HHT due to irregular communications between arteries and veins in the lungs that determine a right to left transit of septic or aseptic emboli, as was the case of our patient.1,3,5-7,9,10PAVMs provide a right to left shunt that allows a bypass from the filtering effect of the lung capillaries.9

This diagnosis can be reinforced by the performance of a transesophageal echocardiogram with a bubble study, confirming a right-to-left passage of bubbles. Ischemic cerebral events can occur in onethird of patients presenting PAVMs, and brain abscess in 5% to 10% of them.9,11In our patient the metastatic spread from the PAVMS was suggested by the septic vascular topographic distribution described in the brain MRI. If left untreated, half of the patients with PAVMs will present those complications, contributing to more neurologic damage than the cerebral arteriovenous malformations itself.7,12

The standard treatment for PAVMS is arterial embolization, as pulmonary lobectomy is a procedure with risks of its own.3,7,8,10Unfortunately, after her first neurologic complication, she was not offered arterial embolization of the PAVMs, enabling other complications like brain abscesses, as was the case. Fortunately, she recovered from the deficits, and underwent arterial embolization of the PAVMs, and later lobar pneumectomy, presenting no further neurologic complications related to the arteriovenous malformations to date.13

Most patients with HHT (80% to 90%) present mutations in either ENG gene that encodes endoglin (HHT type 1) or ACVRL1 gene that encodes activin receptor-like kinase type 1 (HHT type 2).11,13These mutations present a genotypephenotype correlation with specific arteriovenous malformations, justifying the importance of genetic investigation of these families.11,13The ENG gene mutations are related to HHT type 1, with epistaxis and PAVMs appearing at an early age and higher frequency.13 The brain embolic complications are also thought to be more prevalent in patients with ENG gene mutations because of a higher prevalence of moderate to large sized PAVMs.11 In our patient the diagnosis was also confirmed genetically by the identification of a genetic variant on ENG gene, corroborating the relation between the mutation, PAVMs and cerebral complications.

To our knowledge, this is the first case reporting two major neurologic complications in a single patient. Since HHT is a rare condition, practitioners are unaware of its potential complications and the need for family screening.3,5With this example, we want to point out the complexity of HHT, its complications, and above all that we can prevent further morbidity.