Introduction

Thrombocytopenia, first reported to occur in sarcoidosis in 1938,1 is a rare extrapulmonary manifestation, with an estimated incidence of 1%-2%.2 Three main pathophysiological mechanisms have been described, namely immune-mediated peripheral destruction, splenic sequestration, and bone marrow granulomatous involvement; the first mechanism appears to be more prevalent, and has been considered to account for more than 80% of cases of sarcoidosis-related thrombocytopenia.3 Current data on immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) in sarcoidosis are scarce, but suggest an often severe and acute onset, with favourable response to conventional treatment.3 We report a case of newly diagnosed sarcoidosis with pulmonary, cutaneous and bone marrow involvement, presenting with severe ITP, successfully treated with intravenous immune globulin and a prolonged course of corticosteroids.

Case Report

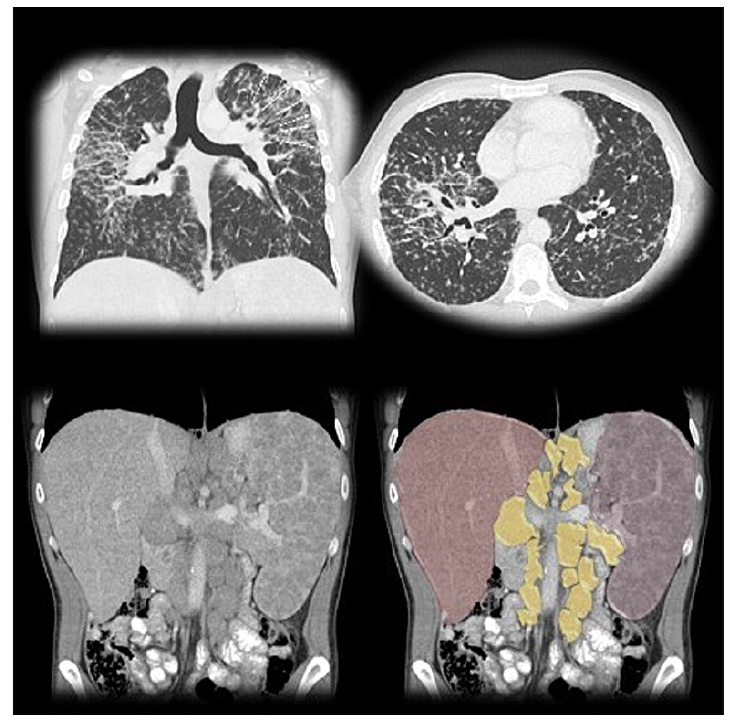

A 44-year-old man of Latin American ethnicity, former smoker with a medical history of dyspepsia and congenital ocular toxoplasmosis, presented to the emergency depart-ment with complaints of progressive asthenia, unintentio-nal 11 kg weight loss, left upper quadrant abdominal pain, and postprandial fullness for 6 months, as well as erythematous, non-pruritic papules on his back (Fig. 1). Prior to hospital admission, a CT scan ordered by his family doctor had shown bilateral upper lobe-predominant pulmonary fibrosis and diffuse bilateral micronodules with a perilymphatic distribution, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly (20.2 cm), and enlarged mediastinal and paraaortic lymph nodes (Fig. 2). These features were considered highly suggestive of sarcoidosis, while a lymphoproliferative disorder seemed less likely. Besides skin lesions, physical examination revealed a palpable splenic edge 4 cm below the left costal margin, and normal cardiac and pulmonary auscultation; no enlarged lymph nodes were detected.

Figure 2: Thoracic CT scan shows perilymphatic irregular nodular thickening, as well as upper lobe-predominant fibrosis (arrows), consistent with stage IV pulmonary sarcoidosis. Abdominal CT scan shows hepatosplenomegaly, with extensive retroperitoneal lymph node enlargement, highlighted in yellow.

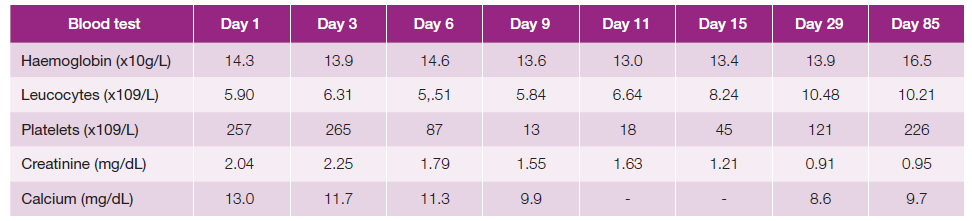

Initial blood tests showed a serum calcium of 13.0 mg/dL and creatinine of 2.04 mg/dL, both returning to normal levels after intravenous hydration and a single dose of intravenous pamidronate 90 mg. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme evel was 461 U/L (normal <85 U/L), and protein electrophoresis showed a polyclonal gammopathy. Complete blood count, liver function tests, thyrotropin, beta-2 microglobulin and urinalysis were unremarkable, and parathyroid hormone and vitamin D25 levels were low. An interferongamma release assay was negative, as was testing for antinuclear antibodies, HIV and hepatitis B and C viruses. Biopsy of a skin lesion re-vealed noncaseating granulomatous infiltration (Fig. 3), with no acid-fast bacilli detected on Ziehl-Neelsen stain, and a diagnosis of sarcoidosis was established.

Figure 3: Skin biopsy showing noncaseating granulomatous infiltration in the reticular dermis (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification x40).

On day 6 of hospital admission the patient developed sudden, severe thrombocytopenia, and by day 9 his pla-telet count had decreased to 13.000x109/L (Table 1), without haemorrhagic dyscrasia. There was no evidence of infection, nor was he receiving drugs potentially associated with thrombocytopenia. Additional investigation showed a normal peripheral blood smear, and positive serology for Helicobacter pylori. A bone marrow biopsy revealed multiple non-necrotizing granulomas (Fig. 4) with negative PAS, Groccott and Ziehl-Neelsen stains, and no evidence of a lymphoproliferative disorder. Bone marrow aspirate showed normal cellularity, with increased megakaryocytes at all maturation stages and slight prominence of juvenile forms, highly suggestive of an immune-mediated process.

Figure 4: Bone marrow biopsy showing multiple epithelioid granulomas without necrosis, and giant multinucleated cells (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification x100).

The patient was given intravenous immune globulin 1 g/kg on day 9, followed by methylprednisolone pulses 500 mg/day for three days, after which we started prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day. Platelet count gradually improved to 45.000x109/L by day 15, and he was discharged. After 3 months of treatment thrombocytopenia resolved completely, and corticosteroid tapering was started; he was also administered therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. At 18 months of follow-up, he maintains a normal complete blood count on prednisolone 5 mg/day, with no side effects reported.

Discussion

An international consensus4 has specified three diagnostic criteria for sarcoidosis: a compatible clinical and radiologic presentation, histologic demonstration of noncaseating granulomas in involved organs, and exclusion of other diseases capable of producing similar findings, all of which were met by our patient, supporting a final diagnosis of pulmonary sarcoidosis, with biopsy-proven cutaneous and bone marrow involvement.

Although well described, the occurrence of thrombocytopenia in sarcoidosis is rare and still poorly characterized, and most of our current knowledge derives from single case reports or small series. In a 1963 series of 145 patients with sarcoidosis,5 1.9% had thrombocytopenia, defined as a platelet count of less than 100.000x109/L. Similarly, in a 40-year follow-up of 640 consecutive patients with sarcoidosis, 0.9% were reported to have pancytopenia secondary to splenic involvement, and none had isolated low platelet count.6

Most of sarcoidosis-related thrombocytopenia cases in the literature were caused by an immune-mediated mechanism. Although numerous autoantibodies can be detected in patients with sarcoidosis, the relationship between this entity and autoimmunity remains unclear.3 The real incidence of ITP in sarcoidosis is yet to be determined, but in a French nationwide epidemiological assessment, sarcoidosis was identified as the cause of ITP in 0.62% of 2882 adult patients.7

Bone marrow sarcoidosis has received much less attention, and its incidence may be influenced by ethnicity. The aforementioned cohort study of 640 patients,6 of whom 95.8% were Caucasian, reported bone marrow involvement in 0.3% of cases, at any time during the 40-year follow-up. On the other hand, in the ACCESS study, where 44.2% of the 736 patients were African American, bone marrow infiltration was present in 3.9% of cases, with a higher incidence observed in this subpopulation.8 Latin American studies are also lacking. In a 24-year follow-up of 21 Mexican patients, 23.8% had bone marrow disease,9 possibly indicating a higher frequency of this extra-pulmonary manifestation in this ethnicity. Although seemingly quite rare, bone marrow sarcoidosis is probably underdiagnosed, due to low physician awareness, and low incidence of severe cytopenias that could justify bone marrow examination. The increasing use of fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography as a diagnostic method for inflammatory diseases, including sarcoidosis,10may be determinant in establishing the real prevalence of bone marrow involvement.

Interestingly, our patient displayed all three described pathophysiological mechanisms for thrombocytopenia in sarcoidosis. It is possible that both splenic sequestration and bone marrow infiltration may have contributed to the low platelet count; however, the sudden onset and severity of thrombo-cytopenia, as well as preservation of the other two blood cells lineages, argue against these being the predominant mechanisms. Bone marrow aspirate findings were highly suggestive of an immune-mediated process,11 and ITP was assumed as the main mechanism. Furthermore, complete response to conventional treatment, and haematological stability after corticosteroid withdrawal, also support the diagnosis.

An association between Helicobacter pylori infection and secondary ITP is well established; although the exact mechanism is not yet completely understood, there is growing evidence that eradication therapy may play a role in improving platelet count.12 Our patient received eradication therapy after resolution of thrombocytopenia. A contributory role of Helico-bacter pylori infection seems unlikely, but cannot be completely discarded, given the fact that corticosteroids may be partially effective in this scenario as well.13

There are currently no guidelines for the treatment of sarcoidosis. Most algorithms suggest initiation of corticosteroids in symptomatic patients, followed by tapering over a minimum of 12 months.14Regarding sarcoidosis presenting with ITP, several reports have documented a favourable response to treatment either with corticosteroids alone, corticosteroids associated with immune globulin, or other immunosuppressive agents.3

This case report summarizes what is currently known about the association between sarcoidosis and thrombocytopenia. It also corroborates the limited body of literature that suggests a usually acute and severe onset of ITP in these patients, with satisfactory outcomes in response to standard management. Severe bleeding and death are uncommon, and long-term prognosis is generally good. Otherwise, unexplained cytopenias in sarcoidosis should prompt bone marrow exami-nation, since granulomatous infiltration, albeit rare, may be pre-sent. Future intervention and follow-up studies will improve our understanding of sarcoidosis-related thrombocytopenia.