Introduction

Dysphagia is a dysfunction of the swallowing process that makes it difficult or prevents oral ingestion of solid, semi-solid and/or liquid foods in a safe, efficient and comfortable way.1 It is a common problem and it is estimated that, during life-time, 1 in 17 individuals develop some form of dysphagia.2 The causes of dysphagia include structural and/or functional changes such as Zenker's diverticulum, laryngectomies, cervical osteophytes, aging or disuse myopathy, and neurological disorders such as stroke, neurodegenerative diseases or dementia.

The loss of swallowing efficiency is a risk factor for dehydration and malnutrition and can compromise the protective mechanism of the airway, leading to respiratory complications such as airway obstruction, aspiration pneumonia, lung abscess, sepsis and death.3,4 Dysphagia is, therefore, considered a factor of poor prognosis in the recovery of patients, contributing to the increase in the use of hospital resources, longer hospitalization and health costs.3,4

There are surprisingly few studies on the prevalence of dysphagia in the hospital population, with some series pointing to values between 12% and 30%,4 but higher values (44%) were found in elderly hospitalized population.5

As it is an underestimated problem, it is often not diagnosed or considered pathology with potential for harmful effects. If well recognized and oriented, it can have a relevant impact on the quality of life and health of patients.

In order to clarify this reality in our population, we developed a prospective hospital-based study, in order to calculate the prevalence of dysphagia in an Internal Medicine inpatient department. It is also intended to identify the factors associa-ted with impaired swallowing in patients admitted to Internal Medicine care and their relationship with complications.

Material and Methods

A prospective, single-site, observational study, eminently non-interventional, was developed. All patients consecutively admitted over a period of 12 weeks to the Internal Medicine Department of Hospital da Luz - Arrábida (Internal Medicine ward and Intermediate and Intensive Care Unit) were included.

The following exclusion criteria were applied: discharged in less than 24 hours, patients without a prescribed oral diet or with a level of consciousness that did not allow safe screening and who refused to enter the study.

After informed consent from the patient or legal representative, demographic data (age, gender), clinical admission main diagnosis (according to a pre-categorized domain), reference to previous dysphagia (reported by the patient or family or recorded in chart) and history of aspiration pneumonia (reported by the patient and/or family and/or recorded in chart) were collected from the clinical records. Comorbid burden was characterized by the Charlson-morbidity Index6 (CCI). We evaluated the presence of criteria for Complex Chronic Patient, using criteria agreed for this purpose and adapted from the international literature7 as the presence of 2 or more of the following: patient above 75 years-old; 3 or more chronic diseases (as defined in the Charslon Comorbidity Index); 3 or more hospitalizations in the last year; 5 or more emergency department admissions in the last year; 5 or more chronic medications. The degree of autonomy was evaluated by the Barthel Index for Activities of Daily Living, taking into account the performance in 10 items - food, transfers, personal hygiene (shaving, washing the face, brushing teeth), use of the toilet, bathing, mobility, going up and down stairs, dressing, bowel and urinary control.8

Dysphagia was identified using the GUSS - Gugging Swallowing Screen scale, widely accepted and validated for this purpose and available in European Portuguese.1 It can be applied at the patient's bedside, classifying patients by severity of dysphagia - no dysphagia (total score of 20 points; success in feeding semi-solids, liquids and solids), mild dysphagia (total score between 15 and 19 points; success in feeding semi-solids and liquids but not in solids), moderate dysphagia (total score between 10 and 14 points; successful feeding for semi-solids but unsuccessful for liquids and no indication for feeding test with solids) and severe dysphagia (total score of 0 to 9 points; unsuccessful preliminary assessment or unsuc-cessful semi-solid feeding).1 The scale was applied by three researchers (JRA, IC, RC), with previous training and qualification for its use. The risk of malnutrition was measured by the NSR - Nutritional Score Risk,9 categorizing individuals without risk (scores equal to 0), increased risk (scores between 1 and 2, with a suggestion to consider nutritional intervention and considering referral to a nutritionist) and high risk (scores greater than or equal to 3, with an indication for referral to a nutritionist for assessment, diagnosis, intervention and nutritional monitoring). The score consists of the sum of the three scores for each evaluated scope - patient's age, compromised nutritional status based on body mass index (BMI) value and subjective assessment of general status, weight loss in the last 3 months and reduction in daily intake in the last week and severity of the disease.

We prospectively surveyed the following outcomes: length of stay, documentation of asphyxia or choking, difficulty in feeding, need for medically assisted tube feeding, bronchial aspiration, aspiration pneumonia, and death.

Data were recorded in digital format using the GoogleForms platform and subjected to statistical analysis using SPSS version 27.10 We calculated relative and absolute frequency, means and standard deviation for each variable. Chi-square and Mann-Whitney U tests were performed to assess the relationship between the presence of dysphagia, defined as a GUSS score < 20, with the different variables analyzed. We assumed a significance level of p < 0.05.

The investigation protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital da Luz - Arrábida and the Learnin-gHealth Data Protection Committee. In case of identification of dysphagia situations, their presence was signaled to the medical team who took the measures they considered necessary, without any additional intervention by the team of researchers.

Results

In the 12-week period, 115 patients were hospitalized. A total of 36 individuals were excluded (26 due to discharge from hospital in less than 24 hours, 6 due to refusal to participate in the study and 4 due to non-compliance with the dysphagia assessment questionnaire).

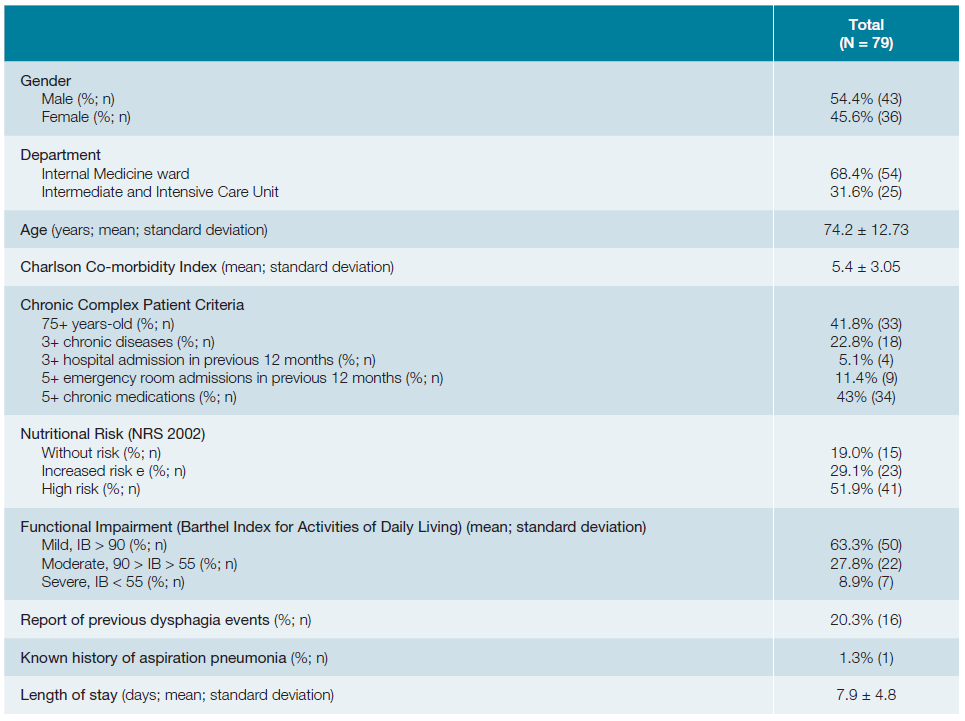

Of the total of 79 patients, one third of the patients were evaluated in the Intermediate and Intensive Care Unit, while the rest were evaluated in the Internal Medicine ward. Sample characteristics are summarized in table 1.

In our sample, 54.4% were male, with a mean age of 74.2 ± 12.73 years. The main diagnoses at admission were cardiocirculatory disease (36.7%), infectious (13.9%), respiratory (10.1%) and neurological disease (8.7%), with an average hospital length of stay of 7.9 ± 4.8 days. The average ICC score is 5.43 ± 3.05. Approximately a quarter of patients (22.8%) had 3 or more chronic diseases and 13.9% were classified as “chronic complex patients”. About a third of patients (36.7%) had moderate to severe functional limitation and 80% were classified as at risk of moderate to severe malnutrition. A history of dysphagia was identified in 20.3% of the sample, but only 1.3% had a history of aspiration pneumonia.

The prevalence of dysphagia in our cohort was 34%. The mean GUSS scale score is 17.68 ± 4.43, with scores indicative of mild dysphagia in 12.7%, moderate in 13.9% and 7.6% of severe dysphagia.

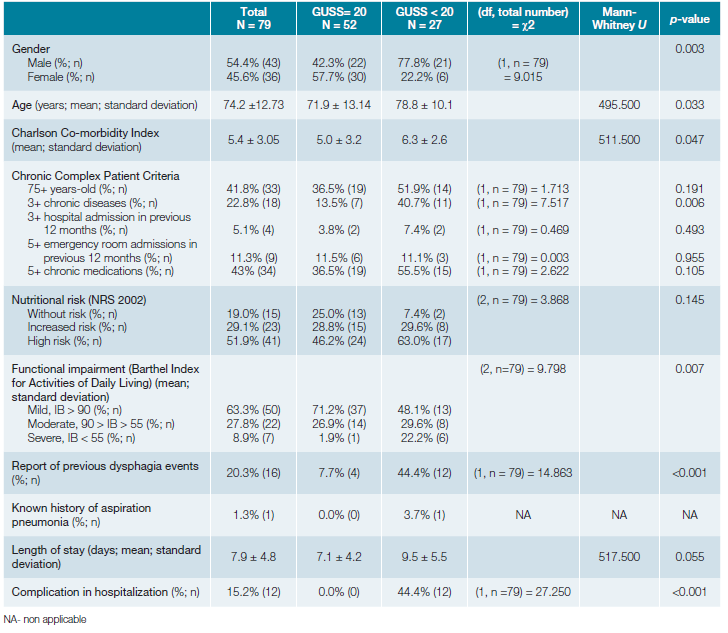

Comparison of the data for the population of patients with and without dysphagia is presented in Table 2. There was a significant relationship between the presence of dysphagia and gender (χ2(1, n = 79) = 9.015; p = 0.003), age (U = 495.500; p = 0.033), Barthel index score at admission (χ2(2, n = 79) = 9.798; p = 0.007), Charlson Comorbidity Index (U = 511.500 ; p = 0.047), presence of 3 or more chronic disease (χ2(1, n = 79) = 7.517; p = 0.006), presence of previous dysphagia (χ2(1, n = 79) = 14.863; p < 0.001). Almost half of the patients diagnosed with dysphagia by the GUSS score, reported previous events of swallowing impairment. Although not statistically significant, there was a trend towards a longer hospital stay in patients with dysphagia. Presence of dysphagia was not related, in the present sample, to admission diagnosis or nutritional risk attributed by NSR2002.

During hospitalization, feeding difficulties were identified in 14 patients (17.7%). There was a need for an alternative route in 1 patient, there were 3 episodes of choking and 2 episodes of bronchoaspiration. The presence of complications in hospitalization was related to the presence of dysphagia (χ2(1, n = 79) = 27.259, p < 0.001).

Discussion

The prevalence of dysphagia in patients admitted to the Internal Medicine department of our institution was 34%, being moderate to severe in 21.5%. Older male patients, with greater functional disability, more comorbid burden and with a previous history of swallowing difficulties were more likely to have dysphagia, as detected by GUSS. About one in six patients developed complications of dysphagia in hospital and their occurrence was related to the severity of the swallowing disorder. These data are in agreement with the scarce literature available.2,11-14Although the present study refers to a single center and with a small sample population, the typology of the population hospitalized in national and international Internal Medicine services is consistent with the characteristics of patients at increased risk for dysphagia that we found in our sample: elderly patients, with pluripathology and reduced functional status.15 This fact justifies the conviction that dysphagia is a highly prevalent and frequently overlooked cross-sectional problem in our wards. These results should be confirmed in a larger population, preferably in and multi-center study.

Conclusion

The prevalence of dysphagia in the population hospitalized in an Internal Medicine department was 34%. Gender, age, comorbidity and dependence are risk factors for the presence of dysphagia. About one in six patients developed complications resulting from this pathology. These data, to be confirmed with a larger study, may justify a universal screening of dysphagia in patients hospitalized in internal medicine services.