Introduction

In 2017, Eikelboom et al published the results of the COMPASS trial.1 This trial studied the net clinical benefit of using acetylsalicylic acid in combination with low dose rivaroxaban versus both acetylsalicylic acid alone and rivaroxaban alone. It was stopped prematurely, due to overwhelming efficacy and concluded that patients with stable atherosclerotic vascular disease have a 24% lower rate of cardiovascular death, stroke, or myocardial infarction with rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) plus acetylsalicylic acid than with acetylsalicylic acid alone. Even when considering the bleeding risk, combination therapy had a net clinical benefit of 20%.1

A more recent study concerning a COMPASS trial subgroup analysis showed that the more risk factors a patient has, the more significant the clinical benefit from this secondary prevention strategy is. The impact of additional risk factors had an additive effect in reducing the number needed to treat (NNT). For instance, a patient with 4 selected high-risk features (polyvascular disease, renal dysfunction, heart failure, and diabetes) presents the NNT of 9 patients/30 months.2

The magnitude of the benefit and the high frequency of cardiovascular disease in internal medicine patients, could led to great enthusiasm among internal medicine physicians. But on the other side, the change in the clinical management paradigm of these high-risk patients and high costs also lead to uncertainty and doubts among physicians.

To clarify these doubts and better understand if COMPASS eligible candidates are among internal medicine patients, we applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to ambulatory internal medicine patients.

Methods

We performed an observational, retrospective, and cross-sectional study in an internal medicine department of a tertiary university hospital.

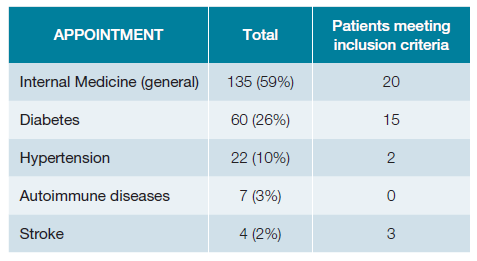

During a 1-month period (March 2022), we assessed all electronic medical records of internal medicine outpatient appointments and previous complementary diagnostic exams screening to assess which patients presented inclusion and exclusion criteria of the COMPASS trial. We screened general internal medicine visits, as well as specific visits, such as diabetes, hypertension, stroke, and auto-immune diseases. Patients attending more than one appointment were only considered once (the first appointment). Age, gender, comorbidities, and current medication were collected.

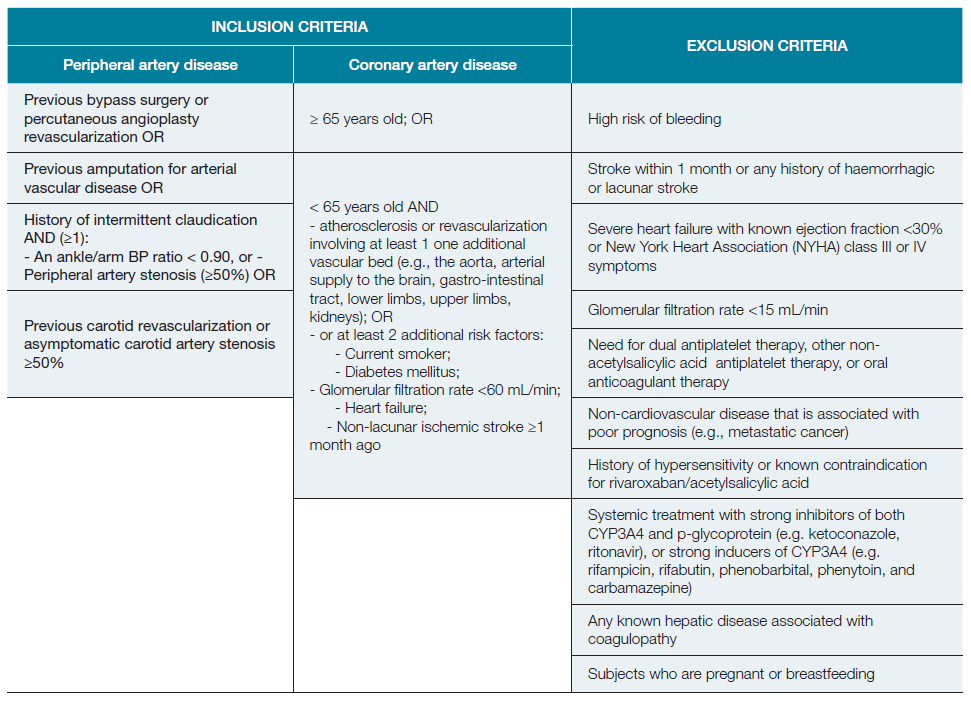

Inclusion criteria included peripheral artery disease (PAD) and coronary artery disease (CAD). Inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Table 1.

Data were analysed using the SPSS 13.0 software. The categorical variables were described as absolute values and percentages and the continuous variables as means and standard deviations. In order to assess the statistical significance of relationships between variables, Chi-square or Fisher test was used to compare categorical variables, and student’s t-test or Mann Whitney U test werw used to compare continuous variables. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Ethical approval was waived by the local Ethics Committee in view of the retrospective nature of the study and all the procedures being performed were part of the routine care of patients.

Results

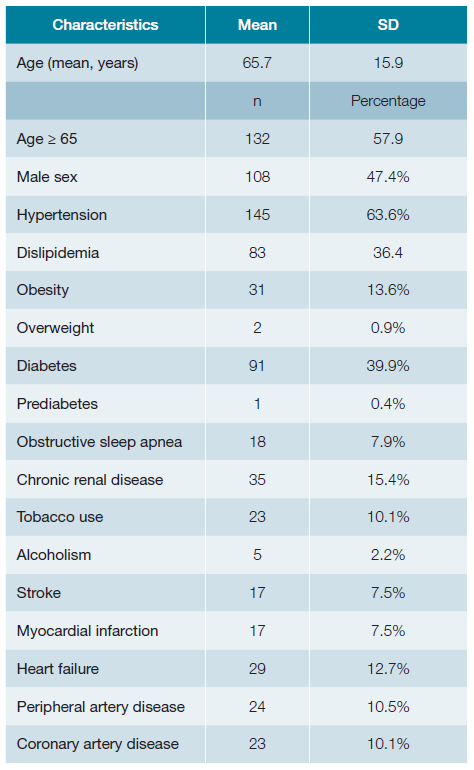

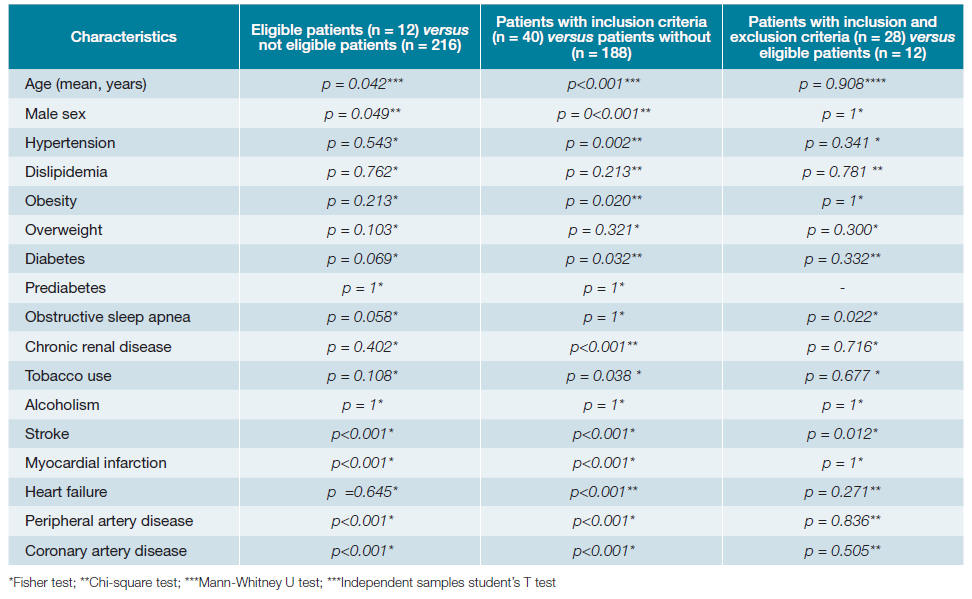

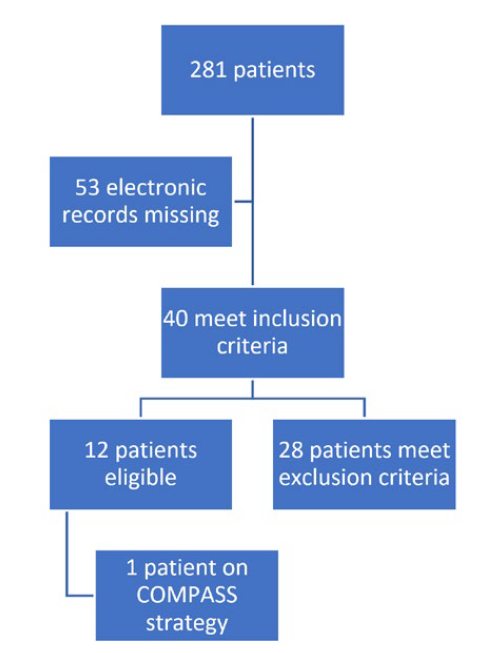

A total of 281 patients’ appointments were screened (Fig. 1). Out of these, 228 had electronic registries, mainly from general internal medicine (59%), diabetes clinic (26%) and hypertension clinic (10%) (Table 2). The mean age was 65.7 years old (SD 15.9) with approximately half of the patients being women (52.6%; n = 120). Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 3, while Table 4 illustrates the comparison between patients meeting the inclusion criteria and those who do not meet them. Table 5 shows the statistical significance of the difference in characteristics between groups.

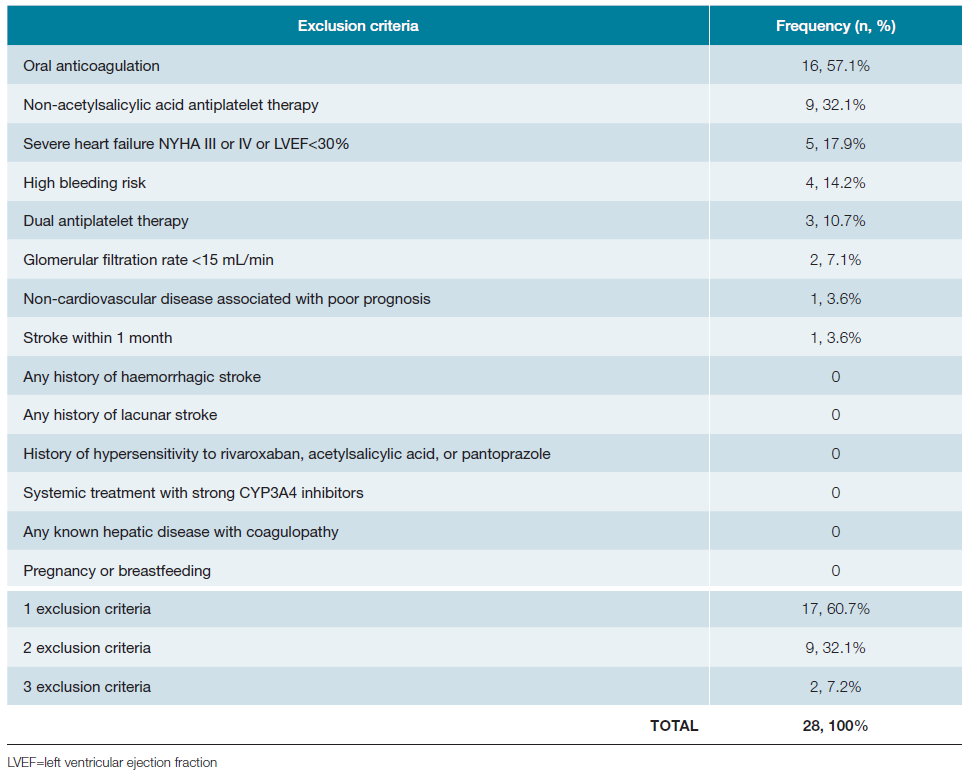

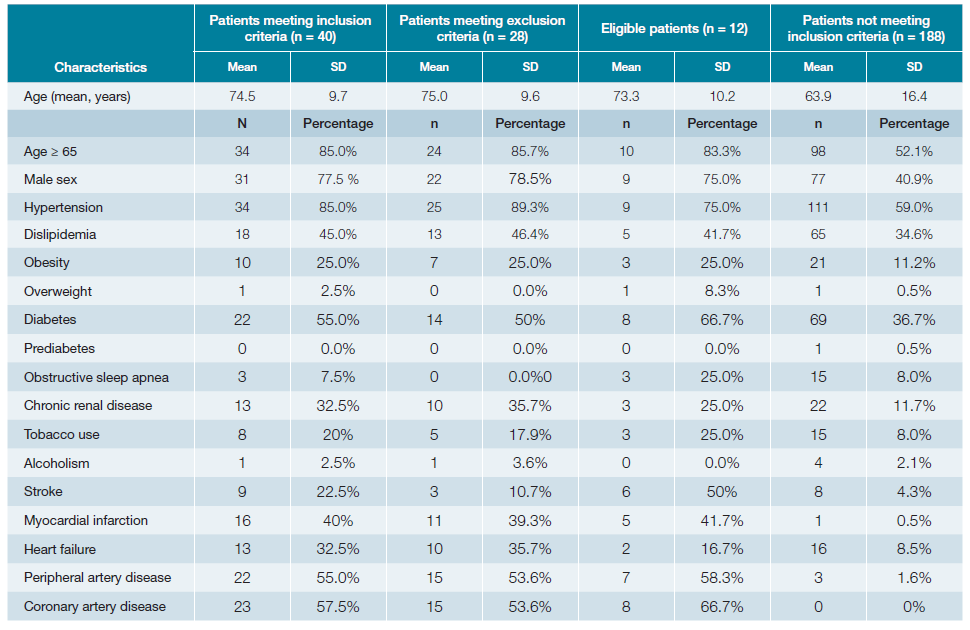

Table 4: Characteristics of patients meeting inclusion criteria, eligible patients and those not meeting inclusion criteria.

Forty patients (18%) met inclusion criteria for COMPASS trial. Among them, 23 (57.5%) had CAD, 22 (55%) had PAD, and 6 (15%) had both.

Among those meeting the inclusion criteria, 70.0% (n = 28) exhibited at least one exclusion criterion. The most common exclusion criterion was the use of oral anticoagulation (primarily due to atrial fibrillation), followed by non-acetylsalicylic acid antiplatelet therapy users (Table 6). Some exclusion criteria could be reconsidered. For instance, those patients on non-acetylsalicylic acid antiplatelet (n = 9) would benefit most from the COMPASS strategy (discontinuation non-acetylsalicylic acid antiplatelet). Patients on temporary dual antiplatelet therapy (n = 3) and those who had a stroke in the last month could potentially become eligible for COMPASS strategy soon, potentially resulting in an increase (13 more patients) in the total number of COMPASS candidates (Table 6). The 9 patients on non-acetylsalicylic acid antiplatelet were taking clopidogrel for various reasons, as: in dual antiplatelet regimen after an ischemic stroke (n = 1), after carotid stenting (n = 3), after PCI (n = 2) or in the treatment of PAD (n = 5). In all these scenarios, the exclusion criteria could fall after a few days or months.

Twelve patients (5.3%) were considered eligible to start COMPASS secondary prevention strategy, based on the application of inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). One patient was already undergoing the COMPASS trial strategy.

Figure 1: Flowchart of included patients applying inclusion and exclusion criteria of COMPASS trial.

This was a 66-year-old man with polyvascular atheroscle-rosis (carotid, coronary and peripheral artery stenosis), diabetes, a history of non-lacunar ischemic stroke and was a current smoker.

Of the 12 eligible patients, the mean age was 73.3 years old (SD 10.2; range from 55 to 93), consisting of 9 men and 3 women. More than half of these patients (n = 8) were from diabetes clinic, while the remaining (n = 4) were from internal medicine clinic.

Discussion

The primary finding of our study is that 5.3% (n = 12) of all patients attending outpatient internal medicine appointments in a single month were candidates for the COMPASS strategy. Moreover, it is anticipated that this number could potentially be higher if some exclusion criteria were resolved, such as the discontinuation of non-acetylsalicylic acid antiplatelet treatment and temporary exclusions like recent non-lacunar ischemic stroke and dual antiplatelet therapy.

When analyzing the characteristics of the studied patients, a high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors is observed (Table 2). Upon comparing patients meeting the criteria for initiating the COMPASS strategy with those without criteria, it becomes evident that the former group is predominantly composed of men (77.5% vs 40.9%, p < 0.001) and individuals of older age (74.5 years ± 9.7 vs 63.9 years ± 16.4; p < 0.001).

Interestingly, the frequency of cardiovascular risk factors among patients in both groups exhibited significant differences regarding the frequency of: hypertension (85.0% vs 59.0%; p = 0.002), obesity (55.0% vs 11.2%; p = 0.020), diabetes mellitus (55.0% vs 36.7%; p = 0.032) chronic renal disease (32.5% vs 11.7%; p <0.001), tobacco use (20.0% vs 8.0%; p <0.001), stroke (22.5% vs 8.5%; p <0.001), myocardial infarction (40.0% vs 8.5%; p <0.001), coronary artery disease (55.0% vs 1.6%; p <0.001) and peripheral artery disease (57.5% vs 0%; p <0.001). The group consisting of patients meeting the inclusion criteria (n = 40) showed a higher prevalence of all the mentioned cardiovascular risk factors. This suggests that individuals eligible for COMPASS in the Internal Medicine clinic are those with known cardiovascular risk factors, in addition to CAD and PAD.

It is worth noting that only one patient was already taking low dose rivaroxaban plus acetylsalicylic acid. This observation may indicate therapeutic conservatism and reluctance among physicians to adopt a new preventive strategy.3 Despite the publication of the COMPASS trial in 2017, the attention of internal medicine physicians has been primarily absorbed by the past two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, possibly resulting in decreased awareness of the benefits of this new treatment strategy.4 On top of that, the COMPASS strategy has a monetary cost that cannot be understated given the average Portuguese salary - around 23€ per month for rivaroxaban 2.5 mg plus aspirin 100 mg for an average gross monthly retirement allowance of 484€ (data from Pordata 2020) and wage of 1361€ (data from Instituto Nacional de Estatística 2021). Since these patients have several comorbidities (such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes) and are already polymedicated, the physicians must weigh the cost when making therapeutic decisions.

Most patients meeting the criteria to begin the COMPASS strategy were not considered eligible due to their ongoing oral anticoagulation for treating atrial fibrillation. Atrial fibrillation is a prevalent condition among patients under internal medicine care, and its frequency tends to rise with age. Furthermore, the patients in our study are relatively old (65.7 years on average; SD 15.9), which is a risk factor for severe cardiovascular and renal diseases, as well as non-cardiovascular conditions associated with a poor prognosis. All these factors stand as exclusion criteria for commencing the COMPASS strategy. We hypothesize that younger patients attending to cardiology and vascular surgery clinics will better fit inclusion criteria when compared to internal medicine patients.

Indeed, data from the REACH registry - a large prospective, observational, international registry of patients at least 45 years old, with either established atherosclerotic disease (CAD, PAD, or cardiovascular disease) or with at least three atherosclerotic risk factors - detected an eligible population of 52.9%. The average age of those patients was 71 years old and 65% were male. The main reasons for exclusion were high-bleeding risk (52%), anticoagulant use (45%), and requirement for dual antiplatelet therapy within 1 year of an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or PCI with stent (26%).6 Luca et al report an eligibility of 44.5% from the START registry, an Italian cohort registry of stable CAD. Those patients were 72 years old on average and 78% were males.7 Data from COPART registry (France) report that 30% of hospitalized patients due to symptomatic lower extremity artery disease are eligible for rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily plus acetylsalicylic acid. The average age of those patients was 67 years old and 77% were men. The main reasons for exclusion were the need of full dose oral anticoagulant treatment, known malignancy, and history of haemorrhagic or ischaemic stroke.8

To our knowledge, this is the first study to apply the eligibility criteria of COMPASS trial to the real-world population of internal medicine clinics, where patients exhibit greater diversity and differ from those seen in other specialty appointments. A previous study in a national cardiology department focused only on patients admitted for ACS in an 18-month period who underwent PCI and were alive at 12-month follow up. The authors conclude that 32% of those patients were eligible to COMPASS strategy.9 This percentage is very superior to ours (5.3%). However, this data refers to a much more selective population and does not represent reality of Internal Medicine ambulatory clinics. Similar to our data, the need for chronic anticoagulation was an important reason for exclusion (32.1% of patients).9

Besides the important input of our study to raise awareness to this new therapeutic strategy, it has limitations. First, the single centre nature, small sample size and retrospective methodology based on electronic record could bias our results. However, besides medical records, diagnostic exams were looked up to increase the grade of certainty regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria. Secondly, we focused exclusively on ambulatory internal medicine patients. However, results do not represent the broader spectrum of internal medicine patients, especially those who are hospitalized. We hypothesize that the results may differ further, possibly yielding an even lower rate of eligible patients. We intend to perform a subsequent analysis of internal medicine inpatients, that soon will allow us to confirm or deny this hypothesis. Finally, high bleeding risk was poorly defined in COMPASS trial, which could lead to different interpretations by the assessors in more dubious situations.

Conclusion

The number of internal medicine patients who are eligible to benefit from the COMPASS strategy is significant, especially when considering that some exclusion criteria are reversible. Internal medicine physicians must be aware of inclusion and exclusion criteria of this new prevention strategy to promptly apply it in clinical practice.