Introduction

Wilson’s disease (WD) is a rare monogenic, autosomal recessive disorder of copper metabolism. It is characterized by hepatic and neurological manifestations with an incidence of up to 1:30 000.1,2

The ATP7B gene on chromosome 13 encodes a copper-transporting P-type ATPase, preferentially located in the liver but also in the brain, which is responsible for transporting copper from the intracellular space to the secretory pathway (excretion into the bile/uptake for the synthesis of ceruloplasmin). Excessive intracellular copper levels lead to oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and ultimately cell death in the affected organ.1-4Pathogenic ATP7B amino acid substitutions vary widely as do their functional consequences and genotype/phenotype correlations remain to be elucidated.2

Both hepatic and neuropsychiatric phenotypes present between the late second and early fourth decades of life. The first group tends to present earlier in life.4

Clinical presentation may be poor or florid. Mutations leading to absent or non-functional ATP7B protein activity, although rare, often determine early-onset, typically hepatic, severe Wilson’s disease. Hepatic involvement is present in virtually all patients with the disease and can range from acute liver failure to asymptomatic cirrhosis.2

The most common presentations are liver disease or neuropsychiatric symptoms.1 The most common neurological symptoms are dysarthria, especially in the early stages of the disease, tremor, parkinsonism, or involuntary movements, including cerebellar dysfunction, chorea, or hyperreflexia.5,6There is no clear correlation between specific ATP7B mutations and the risk of neurological presentation.7

Kayser-Fleischer rings are copper deposits in the cornea, a characteristic feature of WD that can occur in 90%-100% of patients with neurological manifestations, but only in 50% of patients with hepatic manifestations.3

The simultaneous presence of Kayser-Fleischer rings and low serum ceruloplasmin (95% of patients with hepatic presentation) is diagnostic of WD.5

Once diagnosed, medical treatment with copper chelating agents is indicated and in liver affected non-responders, transplantation should be considered as in other liver diseases.1,2,4,6

Case Report

A 20-year-old man was referred to our hepatology clinic after abnormal liver biochemical parameters were detected during a routine occupational screening. These findings prompted further evaluation. Given the patient’s young age and the lack of risk factors for liver disease, a diagnosis of hereditary or genetic disease was readily suspected in the face of abnormal liver imaging and blood tests.

Such abnormalities led to an examination of the patient's two younger brothers, aged 15 and 12 years old, who also had altered liver tests. Their younger brother is being followed up in Pediatrics at another institution - he has confirmed Wilson's disease, although it has not been possible to consult his medical record.

The medical history of both patients was irrelevant. There was no description of any consanguinity in the family. The family history was positive for hepatic disease of unknown etiology as a great-grandmother had died in her fifth decade of life of unspecified liver disease, without any previous alcoholic or toxic exposure, according to the patients’ parents who are both healthy individuals.

Patients were not taking any chronic medication. No allergies, pharmacological intolerances or toxic exposures were reported. Both patients were physically active.

The patients had no regular contact with animals, had not traveled abroad recently and had no other significant environmental exposures.

Both patients were asymptomatic. In a targeted systematic questionnaire, both patients denied having had fever, weight loss, arthralgia, joint swelling/pain or depression/psychotic symptoms. They also denied urinary and gastrointestinal symptoms and had no respiratory or cardiovascular signs/symptoms.

Physical examination on admission revealed no abnormalities in vital signs, and no fever was documented in any of the subjects. Cardiopulmonary auscultation revealed no abnormalities. Abdominal examination was unremarkable, in both subjects, as stigma of hepatic disease was absent. No peripheral edema was found, and capillary perfusion time was <2 seconds in both cases. Neurological and neuropsychological examination on admission was normal in both siblings.

Iris examination by the clinician's naked eye did not reveal any abnormal colouration as both individuals have dark pigmented irises.

INVESTIGATION

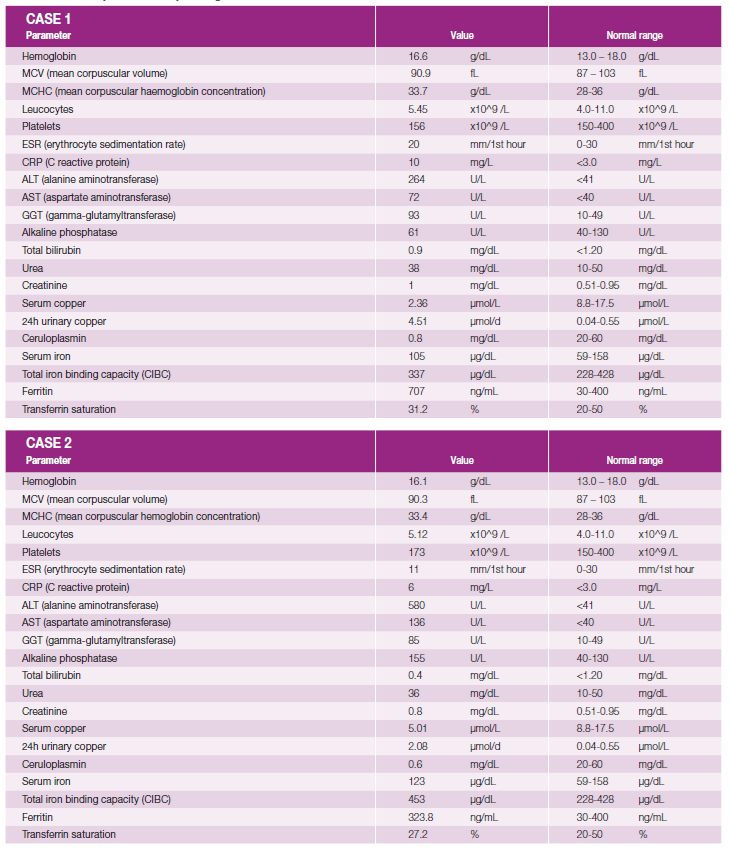

The main laboratory tests performed and normal reference values are detailed in Table 1 and discussed in the following paragraphs.

Complete hemogram and coagulation panel were normal and serum urea, serum creatinine and lactate dehydrogenase and electrolyte panel showed no abnormalities in both cases.

Laboratory tests confirmed elevated AST / ALT and GGT, with values as described in Table 1, showing a hepatocellular pattern with an R factor for liver injury of 13.7 in case 1 and of 11.9 in case 2. Albumin, total and direct bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase were normal in both cases.

Serologies for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis viruses B, C and E and treponemal test were negative in both siblings.

In both cases, there was an increase in serum ferritin. A1-antitripsine levels were normal as were serum protein electrophoresis and immunoglobulin subtype levels. Immunological parameters (antinuclear antibody; anti-mitochondrial antibodies; actin smooth muscle antibodies; anti-transglutaminase antibody) were negative in both individuals.

Serum ceruloplasmin was significantly decreased in both cases (0.8 mg/dL and 0.6 mg/dL, respectively in cases 1 and 2 - normal range 20-60 mg/dL).

The urinalysis was normal but the 24-hour copper excretion was very elevated (8 times ULN in case 1 and 4 times in case 2), corroborating the diagnosis of WD.

In case 1, an abdominal MRI was performed and showed steatosis and numerous nodularities in the liver without any suspicious features suggesting regenerative nodules. No imagery was available in case 2.

Transient elastography was performed promptly during the hepatology consultation. Case 1 was accordingly staged as F4 (elastance 16.3KPa - IQR 17%, CAP 252 dB/m) to raise the possibility of advanced liver stiffness. Case 2 was classified as an F1 (Elastance 7.5KPa - IQR 10%, CAP 180 dB/m), suggesting an earlier stage of the disease.

Liver biopsy was performed with hepatic copper measurement - the patients had values of 192 ug/g and 109.9 ug/g dry tissue. Rhodanine staining showed no copper deposition in either patient.

An appointment was made with an ophthalmologist and both siblings presented with Keyser-Fleischer rings, completing the diagnostic process.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the brain showed no abnormalities in either of the subjects.

Genetic testing confirmed two distinct and rare pathogenic mutations in the ATP7B gene, which were similar in both patients: c.2795C>A (p.Ser932Ter), a nonsense mutation, and c.3402del (p.Ala1135fs) a frameshift mutation, both resulting in a premature stop codon that leads to a structural defect that prevents copper-transporting ATPase 2 from functioning properly.

Using the Leipzig scoring system for Wilson’s disease, as recommended by international associations, both patients scored 9 points, establishing a diagnosis of the condition.1

TREATMENT AND FOLLOW-UP

Both patients were started on a copper chelating agent, D-penicilamin, with the dose progressively titrated up to 250 mg thrice daily (despite being underage, the youngest patient was heavy enough to start on the adult dosing regimen and still comply with the proposed pediatric maximum dose of 20 mg/kg/day).

The younger sibling presented with gastrointestinal adverse effects (diarrhea and abdominal pain) after initiation of D-penicillamine, which persisted despite dose reduction. It was therefore decided to switch the chelating agent and the patient was started on trientine, with good adhesion and tolerability.

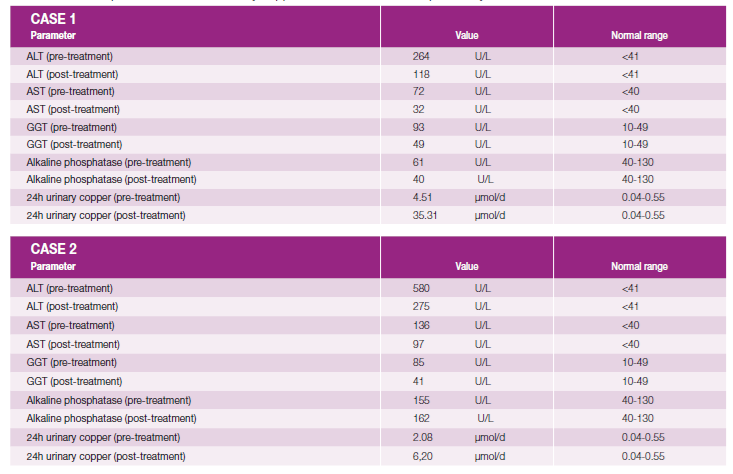

Evaluation of 24-hour urinary copper was performed two months into treatment and both patients showed a significant increase in copper measurements compared to pre-treatment values. Pre- and post-treatment liver enzyme levels are also shown in Table 2.

A dietary plan was also discussed with the patients regarding the consumption of food and water with low levels of copper.

Regular follow-up appointments are scheduled and clinical, laboratory and imaging re-evaluations are performed to ensure optimal management and compliance with the proposed therapy.

Discussion

In a young patient with chronic liver disease, with affected siblings, particularly in the presence of healthy parents, as in these particular cases, the possibility of a genetically determined, recessive condition should be raised at once, and in this context, a WD diagnosis considered and promptly investigated.

In the presence of suggestive features, an organic expression should be thoroughly inquired and objectively sought for using biochemical tools, imaging techniques and clinical capabilities, such as performing a comprehensive physical, neurological and ophthalmological examination to determine whether the diagnostic criteria are met, as was the case in our patients.

In both patients, serum iron showed elevated ferritin, probably secondary to the underlying liver disease, but criteria for suspecting hemochromatosis as a primary diagnosis were not present in either case.

In the liver biopsy, rhodanine staining showed no copper deposition in either patient. which is common in the early stages of the disease.

The presence of Kayser-Fleischer rings in our patients makes this case even more interesting as in predominantly hepatic phenotypes this feature is rare, as stated above.

It is also important to mention the role of non-invasive methods for diagnosing liver fibrosis.

Non-invasive tests such as the 64Cu nuclear medicine bolus infusion test and a test to assess non-ceruloplasmin-bound copper, called relative exchangeable copper, are under development and need to be validated. The genetic test for ATP7B has some limitations because it does not predict the course of the disease and there is a lack of correlation between genotype and phenotype, which could be due to incomplete penetrance, the presence of other modifier genes, lack of clinical diagnostic gold standards, or epigenetic or metabolic factors.8

A recent study concluded that a single measurement of liver stiffness using transient hepatic elastography is not sufficient to accurately stage fibrosis in WD - repeated elastography in the same patient allows a more accurate assessment of disease progression or regression. Combining several methods of non-invasive assessment of fibrosis increases the chance of a more accurate assessment and could be a way to replace liver biopsy in WD.9

The cases of our patients intend to highlight the relevance of a structured initial approach to the diagnosis of liver disease of unknown cause, as the pursuit of a rare diagnosis can be of great importance in ensuring targeted, appropriate and timely treatment, which may improve the patient's outcome.

It should be emphasized that lifelong targeted treatment is required in all patients, even in the absence of symptoms.

Treatment for Wilson's disease has many limitations. Approved treatments are associated with limited efficacy, safety concerns, multiple daily dosing and non-adherence. Novel therapies are being investigated, such as a new pharmacological therapy ALXN1840 (bischoline tetrathiomolybdate, formerly WTX101) and gene therapies such as VTX-801 and UX701. These new therapies will change the lives of people with WD.7

Standard treatment for WD does not always work for all neurological symptoms, and other treatments such as L-dopa, trihexyphenidyl, benzodiazepines and botulinum neurotoxin have been suggested. A 2021 study of six patients showed that there was a good response to the injection of botulinum neurotoxin type A. More widespread use of BoNT/A is recommended for the symptomatic treatment of WD.10

Non-pharmacological measures should be included in the treatment plan and coordinated follow-up is warranted to ensure compliance and to assess clinical and biochemical response. For example, water treatment to reduce copper concentrations is indicated, and people with WD should be encouraged to use tap water for cooking or drinking after running it for at least half a minute or until it has cooled. People with WD should avoid unlined copper mixing bowls and drinking cups. Patients with WD and advanced liver disease may require dietary supplements and should be accompanied by a dietician.7