Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was identified in December 2019 and rapidly spread around the world. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of novel SARS-CoV-2 a global pandemic.1 Portugal had the first confirmed case of COVID-19 on 2 March 2020.2

While SARS-CoV-2 primarily affects the respiratory system, the disease has resulted in systemic sequelae that remain poorly understood, posing a significant global public health challenge. Since the onset of the pandemic, evidence has highlighted an increased prevalence of psychiatric symptoms and diagnosis within the first three months following acute infection.3

Across European Union (EU) countries, an estimated 25 million people (5.4% of the population) live with anxiety disorders, and over 21 million with depression.3 Portugal is the second European country with the highest rate of psychiatric disorders.4 In 2019, Portugal had the highest share of population reporting chronic depression, 12.2%, among EU countries.5 Anxiety disorders affected 16.5% of population.4,6The problem of mental health is serious and real with reports revealing that 1 in every 5 Portuguese suffers, or has suffered, from mental illness, thus placing our country at high risk.4 Similar concerns have been raised regarding psychiatric sequelae of COVID-19, as survivors are at increased risk of mood and anxiety disorders.7 These factors impact health-related quality of life (HRQoL) as it is recognized that COVID-19 may lead to poorer outcomes.8-10

This prospective study aimed to predict the psychiatric outcomes in critically ill SARS-CoV-2 survivors at 3 and 6 months after hospital discharge.

Methods

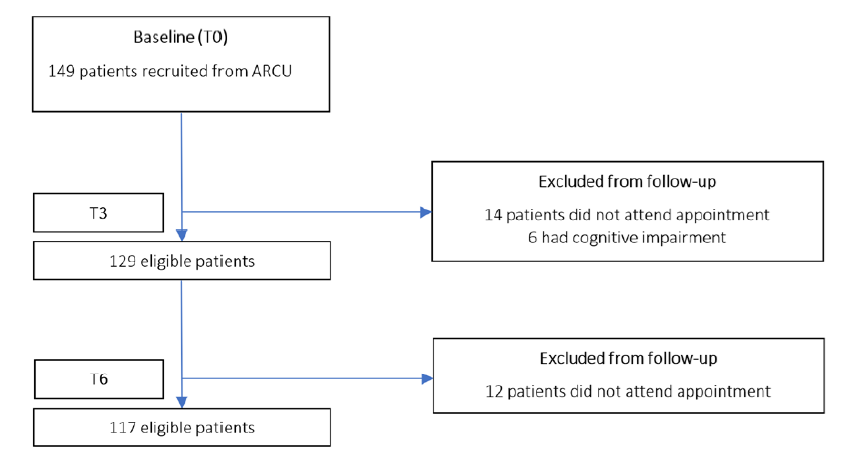

This prospective unicentric study was conducted in two phases and included all critically ill SARS-CoV-2 survivors admitted to a dedicated respiratory unit from November 2020 to November 2021. The inclusion criteria were patients aged over 18 years-old, with COVID-19 diagnosis by PCR on pharyngeal swab and admission to an advanced respiratory care unit (ARCU) for noninvasive respiratory support (NRS). One hundred and forty-nine eligible patients were recruited, at discharge, to an outpatient evaluation at 3 (T3) and 6 (T6) months. Patients with cognitive impairment (ICD 10: F01-F99, G80, Q00-Q07, Q90-Q99), who were unable to complete the questionnaires or refused to participate, were excluded at T3.

PHASE 1. HOSPITALIZATION

A general ward was converted to an ARCU dedicated to critically ill COVID-19 patients. All patients were admitted for treatment with NRS techniques such as high flow nasal cannula (HFNC), continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and noninvasive ventilation (NIV). Patients in need of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), vasopressor support or renal replacement therapy were transferred to ICU. All patients had access to rehabilitation in the ARCU and maintained treatment during all hospitalization.

Demographic and clinical information was prospectively obtained both during hospitalization and outpatient visits. Information regarding demographics, comorbidities [Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) and psychiatric background], education, marital status, NRS techniques, laboratory findings, length of stay and therapeutic ceiling concerning candidacy to IMV were collected during hospitalization. Laboratory findings considered included PaO2/FiO2 as a marker of disease severity; and C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, ferritin and interleukin-6 as markers of inflammation.

PHASE 2. OUTPATIENT VISIT

Outpatient evaluations were made at T3 and T6. In each evaluation, patients were asked to answer anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder questionnaires.

QUESTIONNAIRES

Psychiatric morbidity was assessed with screening questionnaires validated for Portuguese population.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7)11 is a seven-item self-report scale designed to assess generalized anxiety in primary care settings. Each of the seven items is scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The total GAD-7 scale score ranges from 0-21. Cut-offs can be used to classify anxiety symptoms severity as mild (5-9), moderate (10-14) and severe (≥15). When formally validated against diagnostic psychiatric interviews, a GAD-7 score of ≥10 has a sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 82% to detect generalized anxiety disorder.12

The PHQ-913 is a nine-item self-report scale designed to assess symptoms of depression. Each of the nine items can be scored from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), and the total scale score ranges from 0-27. Symptom severity can be assessed through the total score, where PHQ-9 scores of 5-9: mild, 10-14: moderate, 15-19: moderately severe, and ≥20: severe depressive symptoms. The PHQ-9 has been formally validated against structured diagnostic interviews administered by a mental health professional. PHQ-9 score ≥10 has a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 88% to detect major depression.14

PCL-5 is a tool that assesses the presence and severity of PTSD.15 It is a 20-item 5-point Likert (0 = “Not at all” to 4 = “Extremely”) scale assessing the 20 DSM-5 symptoms of PTSD. A provisional PTSD diagnosis was made according to the National Center for PTSD instructions, considering each item rated as 2 “Moderately” or higher as a symptom endorsed, then following the DSM-5 diagnostic rule which requires at least 1B item (intrusion symptoms associated with the traumatic event e.g. intrusive memories, dreams, flashbacks), 1C item (avoidance of trauma-related stimuli), 2D items (cognitive and mood symptoms e.g. distorted cognitions, diminished interests, feelings of detachment) and 2E items (alterations in arousal and reactivity e.g. angry outbursts, self-destructive behavior, sleep disorders). Patients with 3 criteria out of 4 were considered as affected by subthreshold PTSD. Prevalence was also reported using total scores with a cutoff of 30.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

No statistical sample size assessment was performed a priori, and sample size was the number of patients treated during the study period in the ARCU. Continuous variables are described using mean and standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. Categorical variables are reported frequency and percentages. The normality was checked using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Patients’ outcomes were compared, between timepoints, using Paired Student’s t-tests or Wilcoxon for continuous variables or McNemar test for categorical variables.

The association between psychiatric provisional diagnosis at T6, and demographics and data from de hospitalization was calculated using a univariate logistic regression model and data is presented in odds ratio and 95% confidence interval.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 27; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and a p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the ethics committee of Local Health Unit of Tâmega and Sousa (Portugal). Data from hospitalization were prospectively recorded after ethical approval (phase 1). For this purpose, informed consent was waived by the institution due to the heath care burden felt at the time. At the ambulatory evaluation all patients participated voluntarily and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants at T3 (phase 2). All procedures were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Results

One hundred forty-nine patients were discharged to ambulatory follow-up. Of those, 117 patients were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). Four patients were excluded due to dementia and 2 due to Down syndrome at T3. No patient refused to participate or withdraw informed consent during the study period.

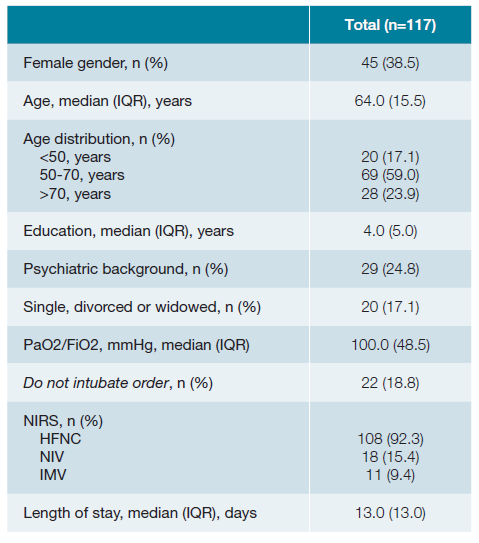

Demographic characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Participants’ age ranged from 25 to 85 years. The majority were men. Forty-five percent had at least one comorbidity included in Charlson comorbidity index and and mean Charlson comorbidity-index was 2.6 ± 2.0 points. The most frequent were diabetes (30.8%), heart failure (12.0%), myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular disease (4.3%), peripheral artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease and solid tumor (2.6%). Twenty-nine patients (24.8%) had previous psychiatric comorbidities: 19 reported depression, 7 anxiety, 4 sleep disorders, 2 psychotic disorder, 2 bipolar disease and 2 PTSD.

Concerning education, 56.4%, 24.8%, 10.3% and 8.5% had 1st cycle-basic education, 2nd and 3rd cycles - basic education, secondary education and university/ postgraduate education, respectively. Twenty patients (17.1%) were single, divorced, or widowed.

More than 90% of patients were treated with HFNC. Eleven patients were transferred to ICU for IMV.

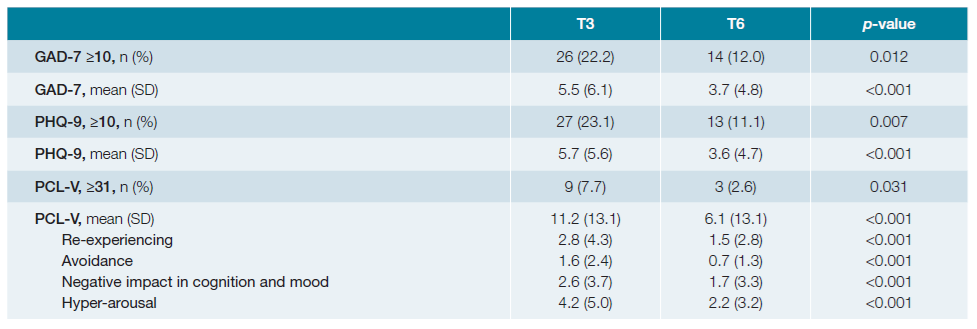

Table 2 presents GAD-7 and PHQ-9 and PCL-V scores evolution over time. At T3 evaluation, 26 and 27 patients were provisional diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder and major depression, respectively. Only 9 patients scored for PTSD at T3. At T6, about half of the patients showed mood and anxiety improvements. This was equally noticed in all PTSD domains.

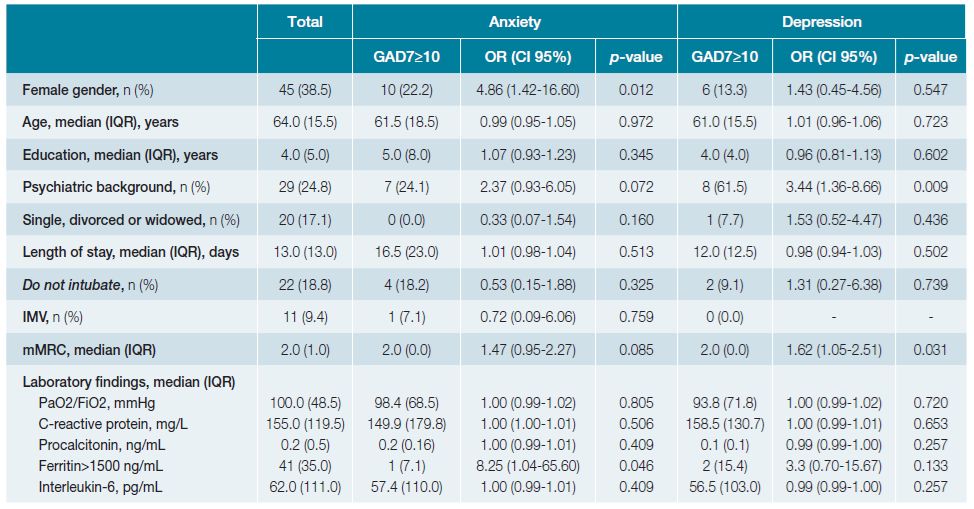

Predictors of psychiatric outcomes were evaluated for anxiety and depression (Table 3). This analysis was not conducted for PTSD due to the low number of diagnosis 6 months after discharge. Female gender and serum ferritin levels were associated with increased risk of anxiety. The likelihood of depression disorder was correlated with the psychiatric background and mMRC dyspnea scale. Interestingly, an association between psychiatric outcomes and age, marital status, education, length of stay, invasive mechanical ventilation, do not intubate order, severity of acute respiratory distress syndrome, was not found.

Overall, 10.3% of patients were referred for further psychiatric or psychological evaluation.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the mid-term psychiatric outcomes among critically ill SARS-CoV-2 Portuguese survivors treated outside ICU. To our knowledge this is the first inquiry conducted on patients admitted to an ARCU. We report a significant improvement in anxiety, depression and PTSD rates over time.

About one quarter of patients reported moderate to severe symptoms of generalized anxiety and major depression, at 3 months outpatient evaluation. This translated into anxiety and depression prevalence rates of 22.2% and 23.1%, respectively. After 6 months, a substantial improvement was noticed with rates of 12.0% for anxiety and 11.1% for depression. These values are slightly lower than anxiety and depression rates noted in studies of the general adult population in Portugal.4-6Psychiatric outcomes vary widely across the world. A review that included 16 research papers on this subject during COVID-19 pandemic in different countries, found that in China depression rates ranged between 8.3%-48.3%, in Italy between 15.4%-17.0% and in Spain ranged from 1.7% for severe depression and 8.7% for mild depressive symptoms.16 We believe that our favorable outcomes result from several factors. Firstly, several studies showed that sociodemographic, economic and health-related factors, such as gender, age, education, income, pre-COVID-19 mental health, have impact on mental health outcomes.17,18Higher levels of psychiatric disorders were reported in younger persons with high income, who also tended to perceive a greater pandemic interference in their daily lives.19 More than 80% of our patients had 50 years-old or more and was retired, a condition that might have limited the impact of pandemics in patients daily habits. Moreover, the majority lived in rural areas, where the access to agricultural and livestock goods might have limited the economic burden.

Lanciano et al 2020,20 found that despite educational qualifications have been classified has a protective factor against perception of worst health, people with a higher education realizes the socioeconomic and political impact of COVID-19 pandemic as more severe, which can exacerbate their mental health. A study conducted during COVID-19 pandemic showed that individuals with high education experienced higher levels of anxiety and depression.21 Over 80% of our sample had only basic education, a factor that might have contributed to our lower depression and anxiety rates.

Second, social support and interaction influence health behaviors and outcomes.22 Due to the pandemic, most people were forced to change their routines, leading to remote work and contact eviction with consequently social isolation. Our study population lived primarily in rural areas near neighbors and relatives and had access to gardens and backyards allowing a safe social interaction, limiting isolation impact arising from COVID-19 restrictions. Additionally, our sample’s marital status is a factor to consider, as only 17.1% were single, divorced or widowed. Having a partner may help cope with mood and anxiety symptoms.

We noticed that female gender has a higher probability of reporting mild to moderate levels of anxiety. Several mental illnesses are more common amongst women, including anxiety and depressive disorders.23 The gender difference in mental diseases is linked to steroid hormones and genes and to a greater propensity for women to report these problems.23,24

Several studies postulate that the psychiatric consequences of COVID-19 might be related to the immune response to the virus. Local and systemic production of cytokines, chemokine, and other inflammatory mediators are induced in response to SARS-CoV-2 acute infection.25 The role of inflammatory markers such ferritin, interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein and in psychiatric outcomes remains an important topic in developing literature. In our population, laboratorial results did not correlate with anxiety or depression. However, the risk of anxiety seems to be associated to higher ferritin levels, although these results must be carefully interpreted due to the wide confidence interval and disperse values founded.

This study has some limitations. First, it is a small convenience sample recruited from a single center in Portugal. It’s uncertain whether our findings can be generalized to the Portuguese population. Larger studies are needed to confirm this data. Second, we do not have information about mental health questionnaires from our cohort previous to SARS-CoV-2 infection, limiting the attribution of psychiatric symptoms/diagnosis to post- COVID-19 sequelae. Third, provisional psychiatric diagnosis was not validated by a psychiatric team, although 10.3% of our patients were referred to a mental health appointment.

Conclusion

Regardless of the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection, anxiety, depression a post-traumatic stress symptoms improvement was noted during follow-up, demonstrating a positive trajectory in mental health outcomes among survivors. Nevertheless, risk factors such as female gender, psychiatric background and mMRC scale emphasize the importance of specific determinants to better understand mental health vulnerabilities. Further researches with larger and more diverse cohorts are needed to better understand the temporal associations between mental health symptoms and their determinants, offering a broader and more comprehensive understanding.

Ultimately, it is imperative that mental health professionals implement proactive interventions aimed to prevent the emergence of long-term psychological disorders. Such strategies should focus on the early identification of at-risk individuals and the effective management of associated factors, contributing to the sustained promotion of mental well-being within the population.