Introduction

TB is a disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Although pulmonary manifestations are the most frequent, the infection can affect any organ in the body. Involvement of the cardiovascular system occurs often, most commonly in the form of pericarditis, aortitis, myocarditis, or mycotic aneurysms.1

Constrictive pericarditis is characterized by the thickening of the pericardium, resulting in a reduction of its elasticity, which leads to restriction of cardiac filling.2,3It can occur after any disease involving the pericardium, but its etiology varies according to geographical and socioeconomic distribution. Thus, in high-income countries, peri- and post-surgical causes account for a significant proportion of cases, whereas in low-income countries, pericarditis of infectious origin, primarily tuberculous pericarditis, is the main cause.4 Diagnosing constrictive pericarditis can be complex, and a multidisciplinary approach is often necessary for an accurate assessment.

Although it is estimated that pericardial TB occurs in about 1% to 2% of patients with pulmonary TB,5,6its progression to constrictive pericarditis occurs in around 30% to 60% of cases.6 The mortality rate can reach up to 90% if not diagnosed in time. Despite Portugal being a country with low TB incidence globally, the number of cases among immigrants has been progressively increasing over the years. In 2020, it accounted for 27.4% of the total reported cases, according to data from the tuberculosis surveillance and monitoring report in Portugal.7

Case Report

A 24-year-old male patient, originally from Brazil, and residing in Portugal for the past five months, presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with a history of non-productive cough, asthenia, night sweats, and unquantified weight loss that had started four weeks ago. He denied chest pain or shortness of breath. Personal history included recent diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection, with a viral load of 1 440 000 copies/mL and CD4+ T lymphocytes count of 92 cells/µL. At the time he was not yet under antiretroviral therapy.

In the ED, an electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed sinus tachycardia, and a thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan showed a pericardial effusion with a maximum posterior thickness of 20 mm, as well as some pretracheal and infracarinal lymph nodes and pulmonary micronodules. Laboratory tests indicated microcytic hypochromic anemia (Hb 11 mg/dL), leukopenia of 3.52 x 109 cells/L with lymphopenia of 0.60 x 109 cells/L, and C-reactive protein of 108 mg/dL.

Due to suspicion of disseminated TB with pericardial involvement, he was admitted to the Infectious Diseases Department. In this context, a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was performed, which revealed severe circumferential with a conventional regimen of isoniazid (H), rifampicin (R), pyrazinamide (Z), and ethambutol (E), along with prednisolone at a dose of 1 mg/kg. The culture of the pericardial fluid in BACTEC-TB radiometric medium tested positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, with susceptibility testing indicating no resistance to first line antituberculosis drugs.

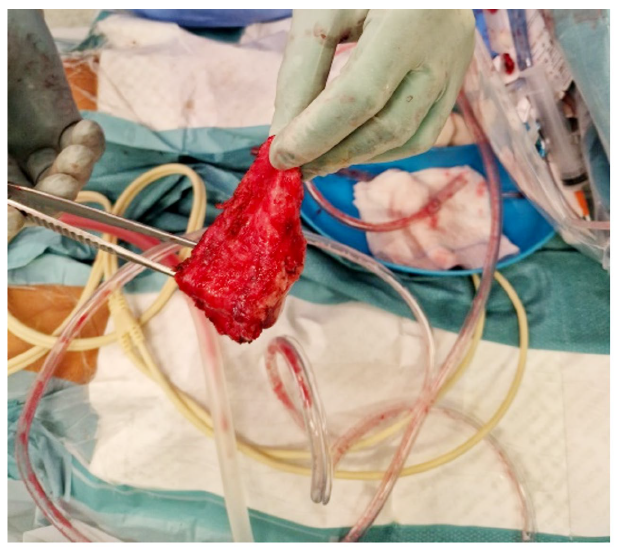

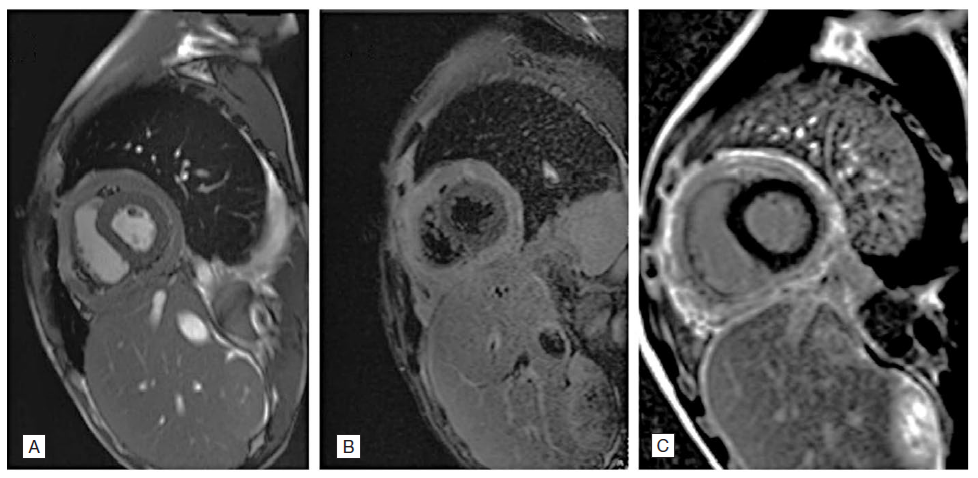

Despite targeted therapy and initial favourable progress (with a reduction in pericardial effusion seen in serial echocardiograms), on the 28th day of hospitalization, the patient developed pleuritic chest pain without relieving factors, accompanied by tachycardia and predominantly vespertine fever. This prompted repetition of the transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE), which showed a resurgence of pericardial effusion with mild to moderate fibrin deposition, pericardial effusion "swinging heart" type, with maximum expression inferoposteriorly measuring 44 mm (in the apical segment), free wall of the right ventricle measuring 39 mm, retroauricular space measuring 35 mm, and lateral space measuring 22 mm. There was slight partial collapse of the right heart chambers (systolic collapse of the right atrium and diastolic collapse of the right ventricle), with more than 25% reduction in the E wave of the mitral valve during inspiration and more than 40% reduction in the E wave of the tricuspid valve during expiration, indicating ventricular interdependence. Considering these TTE findings, an urgent pericardiocentesis was performed for diagnostic and evacuative purposes, yielding 1.150 mL of serosanguinous fluid, characterized as an exudate. The patient was started on antituberculosis therapy as well as slight compromise of overall systolic function, associated with ventricular interdependence and paradoxical movement of the interventricular septum. Given findings consistent with effusive-constrictive pericarditis, a cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) was requested. The MRI revealed a non-dilated right ventricle (telediastolic volume (EDV) 79 mL, 52 mL/m2; telesystolic volume (ESV) 37 mL, 24 mL/m2; stroke volume (SV) 27 mL/m2), with preserved systolic function (ejection fraction 53%), pericardial thickening (15 mm) (Fig.1, panel A), and suggestive calcification adjacent to the right ventricle wall. Real-time imaging demonstrated septal deviation towards the right ventricle during inspiration, consistent with constrictive physiology (Fig. 1, panel C). With the diagnosis of acute constrictive pericarditis, the patient was proposed for partial pericardiectomy, (Fig. 2). At the time of discharge, he had preserved systolic function. He was reevaluated one month after the procedure, with cardiac MRI showing no evidence of constrictive physiology.

Figure 1: (A) Cardiac MRI showing pericardial thickening; (B) STIR image and T2 mapping; (C) Real-time sequence demonstrating deviation of the interventricular septum towards the right ventricle during inspiration, "septal bounce".

Discussion

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a globally significant clinical entity with high morbidity and mortality rates. Therefore, early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are fundamental in combating this disease. The well-established relationship between HIV-infected patients and TB is often linked to higher mortality rates in coinfected individuals.8 The increased severity of tuberculosis in this patient population can be attributed to heightened HIV viral replication induced by the production of cytokines and interleukins because of mycobacterial presence. This leads to a rapid decline in the number of CD4+ T lymphocytes and a higher degree of immunosuppression. Additionally, delays in diagnosis and recognition of the disease can also be more prevalent in this group. Disseminated TB with pericardial involvement presents as a rare manifestation, particularly in developed countries. The spread of the bacillus in relation to pericardial involvement generally occurs through lymphatic pathways or due to proximity to the lungs and/or pleura.6 It can manifest in various forms, including pericardial effusion, constrictive pericarditis, or effusive-constrictive pericarditis.1

Typically, TB presents in an insidious manner, associated with nonspecific symptoms such as fever, cough, night sweats, asthenia, and weight loss.9 However, when pericardial involvement coexists, signs and symptoms of right-sided heart failure may be present. These can include signs of volume overload, such as peripheral edema, anasarca, hepatojugular reflux, jugular distention, or signs of reduced cardiac output such as fatigue and exertional dyspnea.10

The diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis is often complex, and its low prevalence makes identifying key physical examination and historical features an important initial step. Laboratory testing is usually nonspecific. Imaging studies such as echocardiography, MRI and hemodynamic assessment provide the diagnostic workup for constrictive pericarditis, being the latter the gold standard diagnostic test, if non-invasive testing is inconclusive. Treatment often involves diuretics and anti-inflammatory drugs if extensive pericardial inflammation is present. If no reversibility is seen pericardiectomy is warranted to relieve symptoms and avoid worsening of cardiac function.10

In the described clinical case, there was extrapulmonary dissemination with the development of pericardial effusion and progression to acute constrictive pericarditis, despite the early initiation of targeted therapy. Notably, cardiac MRI revealed pericardial calcifications in addition to thickening, which is a specific but infrequent finding in constrictive pericarditis.11

Despite the notable mortality associated with pericardiectomy for TB-related constrictive pericarditis, the patient had a favourable outcome and preserved ventricular function at the time of discharge. In the follow-up cardiac MRI evaluation one month later, there were no suggestive findings of constrictive physiology.

Conclusion

Although a rare condition, constrictive pericarditis secondary to TB continues to be diagnosed, especially in patients from low-income countries with HIV coinfection. Given its significant morbidity and mortality, early diagnosis and treatment with targeted antituberculosis therapy, along with vigilant follow-up, are crucial for a favourable clinical outcome.