Introduction

Medical wards frequently use physical restraints to ensure patient safety and prevent harm.1 Still, their use raises significant ethical concerns regarding patient autonomy, dignity, and potential damage. As healthcare practices evolve, an ethical approach to physical restraints becomes increasingly crucial. Physical restraints involve devices or methods restricting a patient’s movement, ranging from wrist straps and bed rails to more complex devices like specialized chairs.2 These restraints are typically employed when patients are at risk of harming themselves or others, especially in cases of severe agitation, delirium, or cognitive impairment.2

One of the central ethical challenges is the balance between beneficence and respect for autonomy.3 Restraints can prevent harm, such as self-injury or interference with medical devices. The use of restraints, while intended to ensure safety, can restrict a patient’s freedom and dignity, potentially causing psychological distress, physical harm, or long-term trauma, and conflicts with the principle of non-maleficence.4

Internationally, there has been a growing shift toward minimizing restraint use, supported by frameworks such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.5 In Portugal, physical restraints are subject to legal and ethical scrutiny. The Portuguese Directorate-General for Health has issued guidance promoting restraint minimization and advocating for exploring less restrictive alternatives.6 Hospitals and healthcare institutions are encouraged to adopt patient-centered care practices prioritizing respect for autonomy, dignity, and individualized care. Despite these efforts, disparities in practice remain, influenced by staff training, institutional culture, and resource availability.6,7Best practice frameworks emphasize alternatives such as de-escalation techniques, environmental modifications, and enhanced patient observation.8

This article explores the ethical implications of physical restraints, alternative approaches, and the broader ethical frameworks guiding their use, specifically focusing on practices within medical wards. It also highlights the need for comprehensive training, ethical guidelines, and institutional policies to ensure the appropriate use of restraints while safeguarding patient dignity and rights.

A HISTORICAL CONTEXTUALIZATION OF PHYSICAL RESTRAINT IN MEDICINE

The use of physical restraints in medicine dates back centuries, rooted in efforts to manage patients who posed risks to themselves or others.9 Historically, restraint methods ranged from rudimentary tools like ropes and straps to more structured devices, often used in asylums and hospitals during the 18th and 19th centuries.9,10These practices were largely driven by a lack of effective treatments for mental health conditions and a focus on containment over care. Over time, the medical community began to recognize the ethical and psychological implications of restraint use, sparking debates about human rights and the dignity of patients.9

In the 20th century, advances in psychiatry, pharmacology, and patient-centered care led to a gradual decline in reliance on physical restraints.10 However, their use persisted in acute care settings, especially in managing delirium, agitation, or aggression. Internationally, the movement toward restraint-free healthcare has gained momentum, emphasizing alternatives like de-escalation techniques and environmental modifications.

In Portugal, the history of restraint use aligns with broader European trends,10 influenced by changes in medical philosophy and healthcare policy. The country’s commitment to mental health reform in the mid-20th century, exemplified by the closure of psychiatric asylums and the integration of mental health services into general healthcare, laid the foundation for a more compassionate approach. Today, Portugal is recognized for its progressive stance on healthcare, actively working toward minimizing restraint use through ethical guidelines, staff training, and a focus on human dignity, reflecting its broader cultural and policy commitment to patient rights.10

ETHICAL PRINCIPLES AND CONCERNS IN THE USE OF PHYSICAL RESTRAINTS

The application of physical restraints in medical wards raises significant ethical concerns. These concerns revolve around fundamental principles in medical ethics: respect for autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice.11 Each of these principles plays a crucial role in guiding the ethical use of restraints and ensuring that patient rights and well-being are upheld.

Respect for autonomy is a fundamental ethical principle emphasizing the right of individuals to make their own decisions about their health and care.12Physical restraints inherently conflict with this principle by limiting a patient’s freedom of movement. Ethical practice necessitates that restraint use be justified, transparent, and minimal. The moral challenge lies in balancing the need to ensure safety while respecting a patient’s right to participate in decisions about their care.12,13This restriction can be especially troubling when applied to patients who may already be vulnerable due to cognitive impairments or mental health issues. Ethical practice requires that restraints be used only when necessary and that patients or their legal representatives are fully informed and involved in decision-making about the reasons and nature of the restraints.13,14This approach helps maintain trust and up-holds the patient’s autonomy as much as possible.

Beneficence and non-maleficence are also critical ethical principles.15 Beneficence involves acting in the patient's best interest, while non-maleficence, or "do no harm," requires minimizing potential harm. In restraints, beneficence involves using restraints to prevent damage and ensure safety. Providers should use the least restrictive methods possible and ensure that restraints are applied to minimize discomfort and distress, adhering to strict guidelines for their application.16 Still, it must be balanced with the principle of non-maleficence, which is the obligation to avoid causing harm. The use of restraints should be justified by the potential benefits, such as preventing self-harm or injury, while mitigating any physical or psychological damage caused by the restraints themselves, like physical discomfort, psychological distress, and reduced quality of life. Physical restraints can undermine a patient’s sense of self-worth and respect, mainly if restraints are applied degradingly or uncomfortably.17 Regular assessments are necessary to evaluate whether the benefits of restraint outweigh the possible risks and harms, ensuring that restraints are genuinely in the patient’s best interest.16 The design and application of restraints should prioritize patient dignity and comfort, with providers striving to use the least restrictive methods only after less restraining interventions have been exhausted.13,16The patients should be monitored for signs of distress and given regular opportunities for movement and comfort. Restraints should also be used for the shortest duration possible, with ongoing reassessment to determine if they can be removed. Healthcare providers should receive training in the ethical implications of restraint use and alternative strategies for managing challenging behaviors. Techniques such as de-escalation, behavioral interventions, and environmental modifications can often prevent the need for physical restraints.17 A practical example of de-escalation would be a nurse calmly addressing an agitated patient who is shouting in frustration by using a soothing tone, actively listening to their concerns, and reassuring them that their needs will be met. For behavioral interventions, a caregiver might use positive reinforcement by praising a patient for sitting calmly during a medical procedure or redirecting their focus to a puzzle or familiar object when they show signs of agitation. An example of environmental modifications could be adjusting a noisy hospital room by closing the door, dimming harsh overhead lights, and ensuring the space is free from clutter or objects that could cause distress to the patient.

Fairness and justice also present essential ethical concerns.18 Applying physical restraints should be equitable and free from bias or discrimination. This means that restraints should not be used disproportionately or unjustly, and all patients should be treated equally and carefully.18 There must be clear, objective criteria guiding the decision to use restraints to prevent decisions from being influenced by convenience or prejudice. Furthermore, healthcare providers should be trained to recognize and mitigate unconscious biases that may affect their choices regarding restraint use.

Patient-centered care plays a crucial role in addressing the concerns surrounding the use of physical restraints, focusing on the individual needs, preferences, and well-being of the patient.12,15In this approach, healthcare providers prioritize the patient's comfort, autonomy, and dignity by exploring less restrictive alternatives, such as de-escalation or behavioral interventions, before resorting to physical restraints. This care model encourages open communication between patients, families, and healthcare teams, ensuring that decisions are made collaboratively and transparently. By keeping the patient at the center of care, patient-centered practices aim to minimize the emotional and physical harm often associated with restraints and create a more supportive, respectful healthcare environment.12

ALTERNATIVES TO PHYSICAL RESTRAINTS

Alternatives to physical restraints in medical wards focus on safety while preserving patient autonomy, dignity, and comfort through a comprehensive and multifaceted approach.19 One key strategy is environmental modification. By adjusting the ward setup, staff can create a safer, more comfortable space that reduces the need for restraints. This includes using low beds to prevent fall injuries, bed alarms to alert staff to movements, and adequate lighting to avoid disorientation.19,20 Removing hazards like sharp edges or clutter and designing calm and minimally stimulating spaces can also help prevent agitation.20 Increased supervision offers another restraint alternative, providing close, direct observation to ensure safety without physical constraints. Continuous monitoring by healthcare staff or trained volunteers allows immediate assistance. At the same time, frequent check-ins with patients, particularly those at risk of falls or confusion, help maintain a sense of presence and reassurance.20 Technology also adds an innovative dimension to restraint-free care. Wearable sensors and non-invasive monitoring devices enable real-time tracking of patient health and behavior, allowing proactive interventions without the need for restraints.20

Behavioral strategies further support patients by managing agitation and distress.21 Techniques like verbal de-escalation help defuse tension, while positive reinforcement rewards calm, cooperative behavior. Adjusting communication styles to be precise, gentle, and comforting reassures patients and reduces their need to act out.21,22These strategies are especially effective when staff are trained in therapeutic communication and are aware of individual patient needs. Sensory and comfort measures provide physical and emotional comfort to soothe agitated patients.23 Items such as soft blankets, pillows, and personal belongings from home can offer familiarity and reassurance. Sensory aids like earplugs, eye masks, or calming music reduce over-stimulation, while therapies such as aromatherapy or gentle massage promote relaxation, allowing patients to rest and reducing the likelihood of disruptive behaviors.

Engagement and activity programs tailored to individual interests and cognitive abilities offer meaningful stimulation that reduces boredom and restlessness.24Activities can range from structured recreational therapy and gentle physical activities to therapeutic programs, such as reminiscence therapy, which involves discussing memories to connect with patients personally.25 These programs decrease the likelihood of agitation or disruptive behavior by providing patients with enjoyable, engaging options. Physical and occupational therapy encourage safe, supported movement to address restlessness and maintain mobility. Physical therapy promotes regular, safe exercise tailored to the patient’s abilities, which can prevent stiffness and frustration from long periods of inactivity.26 Occupational therapy engages pa-tients in meaningful activities, providing a productive outlet and reducing restlessness and agitation.24

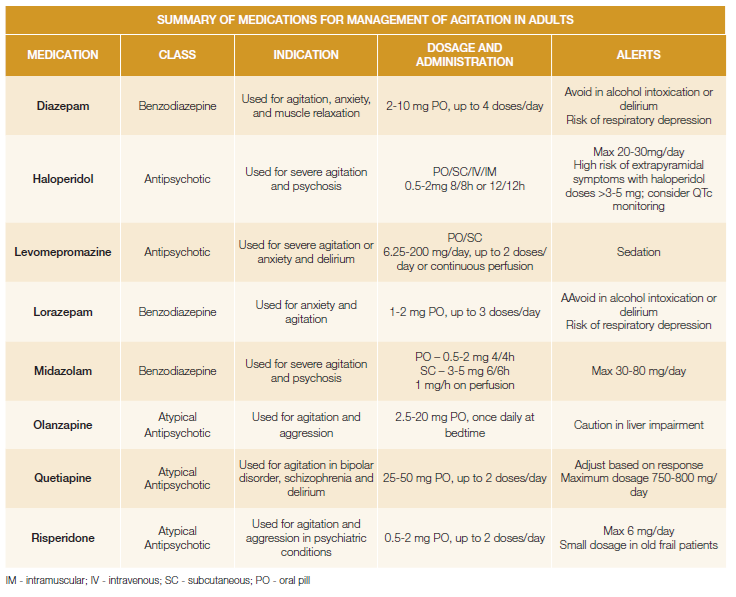

Medication management is essential in minimizing restraint use (Table 1).26 Regular medication reviews allow pro-viders to optimize treatments, addressing symptoms that may contribute to confusion, agitation, or distress. Instead of sedatives, healthcare providers can consider medications that help patients stay calm without impairing mobility or awareness, preventing behaviors that might otherwise lead to restraint use.27,28

Family and caregiver involvement is another valuable alternative to restraints.29 Family members bring familiarity and comfort, reducing stress and anxiety in patients who might feel isolated or distressed, and educating families on how to engage and reassure their loved ones safely and effectively further supports the patient’s emotional and physical well-being, often diminishing the need for restraint interventions.29 Personalized care plans that address each patient’s unique needs, routines, and preferences play a significant role in restraint alternatives. By identifying specific triggers for behaviors that might otherwise lead to restraint use, caregivers can take proactive steps to avoid these situations, reducing the likelihood of agitation or distress. Such personalized care respects individual patient autonomy and promotes a more effective and compassionate approach to care.30

Lastly, technology solutions provide innovative support to enhance safety without restraints.31Tools like fall detection systems, wearable alarms, and discreet monitoring devices offer nonintrusive ways to promptly ensure patient safety and alert staff to potential risks.31,32These solutions support patient freedom of movement while providing healthcare providers with effective means to monitor and respond to patient needs.

DISCUSSION ON PHYSICAL RESTRAINT IN DIFFERENT HOSPITAL ENVIRONMENTS

The use of physical restraints in healthcare settings varies significantly across medical and surgical wards, psychiatric wards, and emergency rooms, reflecting the differing patient needs, risks, and objectives of care in these environments.

In medical and surgical wards, physical restraints are typically employed to prevent patients from harming themselves, such as pulling out medical devices like IV lines, catheters, or endotracheal tubes.33 Patients in these settings may be confused due to conditions like delirium, dementia, or post-operative disorientation. Restraints are often viewed as a last resort when other strategies, such as frequent monitoring, reorientation, or family involvement, have failed. In psychiatric wards, the use of restraints is more complex due to the nature of mental health conditions.34 Restraints may be necessary to manage acute episodes of aggression, self-harm, or severe agitation when patients pose a danger to themselves or others. However, psychiatric care places a strong emphasis on minimizing restraint use through de-escalation techniques, therapeutic communication, and creating a calming environment. The ethical concerns around autonomy and the potential for trauma are particularly pronounced in this context, requiring staff to employ rigorous protocols and provide thorough post-restraint debriefings.

In the emergency room (ER), the fast-paced and high-stress environment often leads to restraint use for patients who are violent, intoxicated, or in acute psychiatric crises harm.7,33The primary goal in the ER is immediate safety for both patients and staff. However, the transient nature of care in this setting can make implementing alternatives like de-escalation or behavioral interventions more challenging. Communication between the ER team and psychiatric or social services is critical to ensure continuity of care and reduce the risk of restraint-related harm.7,33

ETHICAL AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK OF PHYSICAL RESTRAINTS IN PORTUGUESE HEALTHCARE

National legislation, European Union regulations, and international human rights standards primarily influence Portuguese law on physical restraints.35 The critical legislative documents include the Portuguese Civil Code,35 the General Health Law,35 and specific guidelines issued by the Portuguese Health Authority.6 These legal instruments ensure that physical restraints are used appropriately and ethically in healthcare settings.33-36

The use of physical restraints in Portugal is guided by the principle of necessity, which mandates that restraints should only be applied when necessary to prevent imminent harm to the patient or others.6 This principle is rooted in national and international human rights laws, including the European Convention on Human Rights.33-35According to the General Health Law, any restraint must be justified by thoroughly assessing the patient’s condition and the risks involved. The law emphasizes that restraints should be a last resort after other less restrictive measures have been exhausted.7,36

Respect for patient autonomy and dignity is a fundamental ethical concern in Portuguese law. The Portuguese Constitution33-35guarantees the protection of individual rights, including the right to personal integrity and dignity. This constitutional protection is reinforced by specific regulations governing physical restraints. Healthcare providers must ensure that patients or their legal representatives are informed about the reasons for restraint use and are involved in the decision-making process whenever possible.6This approach aligns with international ethical standards, which stress the importance of informed consent and patient involvement in care decisions.5

Portuguese law requires regular monitoring and review of restraint practices to ensure they are applied ethically and effectively.6 The Directorate-General for Health guidelines stipulates that healthcare institutions must establish protocols for monitoring and evaluating restraint use. This includes periodic reassessment of the necessity of restraints and documentation of their use. The goal is to minimize the duration of restraint application and to ensure that the use of restraints is proportionate to the risks involved.6

In Portugal, ethical oversight is provided through various mechanisms, including ethics committees and regulatory bodies.35 These committees review restraint use cases and ensure that moral standards are upheld. They also offer guidance on best practices and help address any concerns related to applying physical restraints.6,36This oversight helps maintain high ethical standards and protect patient rights within the healthcare system.

CONCLUSION

An ethical approach to physical restraints in medical wards requires balancing patient safety with respect for autonomy and dignity. Healthcare providers should prioritize thorough assessments, explore alternatives, and adhere to moral principles to maintain high standards of care. Continuous reflection, empathy, and improvement are key, supported by ethics committees, practice transparency, and ongoing research into less restrictive alternatives (Table 2).

Portuguese law emphasizes the ethical use of physical restraints through guidelines on necessity, proportionality, informed consent, and regular monitoring, aligning practices with national and international standards.