Introduction

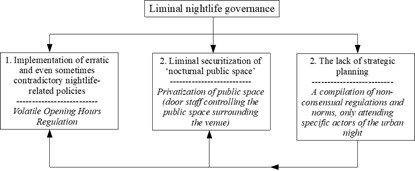

The expansion and commodification of tourist-oriented and youth-oriented nightlife in central urban areas of many European cities has involved the emergence of certain challenges for the governance of the urban night in these cities (Brands and Schwanen, 2014; Talbot, 2011). Among many other issues related to environment, public health, labor protection and social rights, the worsening of community livability during nighttime hours is one of the most controversial and conflictual topics affecting many European cities (Demant and Landolt, 2014; Giordano, Manella, Rimondi and Crozat, 2019; Hadfield, 2009; Tutenges, 2009). By focusing on the case of the former harbor neighborhood of Cais do Sodré, this short research paper discusses some findings regarding the role of both local and national administration in promoting a model of liminal governance of the Lisbon nightlife. By liminal nightlife governance, we mean a precarious, unsustainable and non-participative public-led interplay between the privatization of urban space, leisure and cultural practices and aspects of liminality on public safety in nightlife districts, as a result of the (neo)liberalization of the opening hours regulation. In this sense, this short paper also explores how the institutionalization and everydayization of liminal nightlife governance is operated in Cais do Sodré. Finally, this paper will conclude by indicating that the rise of an extremely commodified ‘right to leisure’ in central areas of the city in recent years has led the ‘right to (neoliberal) leisure’ to de facto become more important than the constitutional ‘right to rest and/or sleep’, undermining community livability and the coexistence between partygoers (most of them tourists and international students) and city residents.

The research presented in this article derives from the set of tasks performed within the SAFE!N Local Intervention Project: Safer Nightlife Label in Lisbon, funded by the BIPZIP Local Development Program of Lisbon City Council (2015-2018), and is mainly based on a critical policy ethnography (Dubois, 2015) carried out between October 2015 and May 2018. Moreover, as a result of the authors’ alignment with the idea that “ethnography is an art of the possible” (Hannerz, 2003, p. 213), this research combined observational fieldwork and participatory research methods (Bergold and Thomas, 2012). While the observational fieldwork was conducted from October 2015 to March 2018, the authors participated in a set of informal and semi-structured interviews (approximately 30) and focus groups (2) with different relevant informants (municipal officials, venue owners, bartenders, security staff members, local residents, and partygoers). Interviews and focus groups took place during the first phase of SAFE!N, between November 2015 and October 2016.

Figure 1: Source: Top Left: City of Lisbon, with Cais do Sodré location indicated by authors. Bottom Left: Aerial picture of Cais do Sodré. Right: early morning on Pink street Both pictures on the left taken from Google Earth in 2019. Right picture taken by the first author in 2020.

Finally, and importantly, a short ethical and legal note should be mentioned. This research has followed both European and national legal rules on research ethics, with special care taken regarding personal data collection, use, storage, and processing. All participants’ personal details, interview recordings and transcriptions were stored securely and were accessible only by the authors. Transcripts of interviews were anonymized, and personal details were kept in a separate secure file. The authors explained the purpose of the research to all participants approached for the interviews, who were provided with an accessible means to contact the main author to ask at any time to be excluded from the research process. None of the participants requested this. In addition, neither underage individuals nor participants belonging to vulnerable groups participated in this research. Moreover, the authors guaranteed confidentiality in conducting ethnographic research as recommended by both the European Commission Ethics Guide on Ethnographic Research and the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity. The following section aims to offer an overview of the origins, development, and current status of nightlife governance, with special attention to the case of European cities.

The right to rest: A fundamental pillar in nightlife governance

Academic literature on nightlife governance focuses largely on British cities and towns. Moreover, the local administrations of many Western cities have developed nighttime strategies and policies focused on the maintenance of law and order (Beer, 2011). As a result, many scholars have taken both security-centered and/or liquor-centered approaches to the study of governance of the urban night (e.g. Hadfield, Lister and Traynor, 2009; Lovatt, 1996; Warren and Palmer, 2014). However, others have offered alternative, non-linear perspectives on the governance of nightlife in the post-industrial city (Giordano, Manella, Rimondi and Crozat, 2019; Nofre, 2018). Nevertheless, and surprisingly, the rapid expansion of the nighttime leisure economy in ‘tourist cities’ of southern Europe, and the consequent challenges regarding the governance of ‘touristified nights’, have not been sufficiently addressed to date by the academic community.

One of these critical challenges, which is yet to be addressed by both academia and the administration, is the worsening of community livability, namely the right to rest that has become synonymous with the right to sleep during nighttime hours. The right to rest has its roots in Article 24 of the UN Declaration of Human Rights (1948), which states that “everyone has the right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay”, as well as several workers’ rights regulations, establishing the separation between working and leisure hours, becoming an important aspect of contemporary societies and their economies. Interestingly, the right to rest as defined in Article 24 is intricately linked to leisure (and its commodified version). This is of great interest when both rights coexist within the nightlife spots of our (neoliberal) cities. In the academic subfield of ‘night studies’, to date, scholars have (inexplicably) failed to pay enough attention to the right to rest and/or to sleep, with a few exceptions for some southern European cities such as Milan and Turin (Ottoz, Rizzi and Nastasi, 2018), the Alaçatı Village in Turkey (Bilbil, 2018), and Montpellier and Bologna (Giordano, Manella, Rimondi and Crozat, 2019).

In fact, noise may be conceptualized as “the absence of silence” (Bijsterveld, 2008, p. 5) in the context of excessive nightlife noise (Bilbil, 2018). Ebru Tekin Bilbil offers an extraordinary study on noise as one of the negative environmental impacts of tourism. According to the author, noisy nights can be seen as the result of an intense nightlife commercialization that is often favored by policy inaction in regard to noise during night-time hours. In the face of this, Bilbil argues that excessive noise is eventually accepted among some residents, while at the same time, those who resist become silent. The the connection between those who accept the noise and those who resist it is simultaneously lost, the responsibility to overcome noise is individualized, and de-territorialization and re-territorialization occur, since those who resist are forced to move to other neighborhoods of the city. This is the case of Cais do Sodré in Lisbon, where the public-led promotion of a liminal nightlife governance clearly jeopardizes residents’ constitutional right to rest and/or sleep.

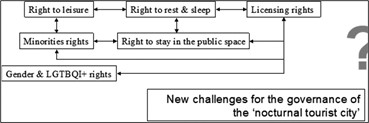

The next section will show how this liminal governance could also be defined as a contradictory and/or unplanned evolution of regulations and standards related to city nightlife that provokes an ‘unresolved clash of rights’ (see Figure 2).

Cais do Sodré, a former harbor area transformed into a nightlife district: A short description

The choice of Cais do Sodré as our case study is not accidental. The origins of the modern night in this former harbor neighborhood date back to the beginning of the twentieth century, when several companies related to maritime trade (i.e. ship-owners, shipbuilders, insurance companies, conveyors, etc.) established themselves in the area. Since the early 1920s, the intense harbor-related economic activity in the area has given way to the spread of many small food and beverage establishments, among many other commercial activities (both formal and informal). Interestingly, it was in the 1930s and 1940s that many seamen started to frequent cheaper bars situated in the back streets of Cais do Sodré, such as Nova de Carvalho Street. A few informal brothels also opened in the area, in the location of the present Pensão Amor (Love Hostel, in Portuguese), a 5-storey building that, many decades later (in 2011), would be converted into one of the most exclusive clubs in the city. The creation of new venues in the early 1970s (e.g. Jamaica Discotheque, Shangri-La, Texas or Tokyo) and their importance as meeting places for local young writers, actors, left-wing thinkers -attracted by the “red-light district environment” of Cais do Sodré- led to the creation of new “festive” atmospheres coexisting with the sordidness, misery, and marginality that characterized the area until the end of the 2000s, when the first Erasmus students began to frequent the area seeking an authentic local nightlife. However, this nocturnal scenario has changed radically: while in 2009 there were fifteen nightlife venues operating in the area, this number had multiplied fivefold by July 2017 (Nofre, Martins, Vaz, Fina, Sequera and Vale, 2019), with the highest concentration of venues situated along the world-famous Pink Street (Nova do Carvalho Street), the new nickname for this nightlife district.

The Pink Street rebranding process dates back to early 2010, when the City Council agreed to support new private initiatives which were mainly oriented towards transforming the area into a new creative district focusing on innovative production and consumption, as well as featuring a vibrant mix of local creative entrepreneurs, live music venues, restaurants and popular meeting places. In November 2011, Nova de Carvalho Street was closed to traffic and pedestrianized. In September 2013, a partnership formed by the Cais do Sodré Venue Owners’ Association, Absolut Vodka, and José Adrião Architect Studio joined forces with Lisbon City Council to create a new economic and cultural dynamic in the area, painting the asphalt pink (see Figure 3 below). The creation of this nightlife spot and associated branding activity led by the local administration was carried out in partnership with Cultural Trend Lisbon, a culture and music promotion agency that also runs Music Box (formerly Texas Bar), a night club that opened in Nova do Carvalho Street in November 2006. The huge success of Pink Street in Cais do Sodré among local upper-middle classes was also fueled by the re-opening of Pensão Amor as the most chic lounge club in the city and recently converted into a very expensive tourist-oriented venue. In turn, many local bars have experienced changes to their customer base since the creation of Pink Street. The huge influx of tourists enjoying the nightlife offered by Cais do Sodré over the past five years has resulted in the spatial displacement of locals who gentrified the night of Cais do Sodré in the mid-2010s, and who prefer instead to patronize other areas that had not yet been touristified yet, such as the riverside district of Marvila.

The (neo)liberalization of licensing and opening hours regulation in ‘nocturnal lisbon’: an example of ‘ghost policies’

The transformation of the former Cais do Sodré into a trendy nightlife spot for (mostly upper-middle class) locals in the early- and mid-2010s, along with the massive influx of thousands of tourists and international students in these last five years, has led to a rapid deterioration of community livability in the area during nighttime hours, as expressed by residents’ associations and posts on social media. In this sense, our main objective in this paper is to examine how the privatization and liminality of public safety in nightlife districts and the (neo)liberalization of opening hours regulation in the form of unclear -sometimes even contradictory- nightlife-related regulations, standards and laws at local and national level has promoted this negative situation regarding the governance of nightlife in Lisbon.

Figure 3: Note: Source: A queue of tourists ready for a night on the town, waiting to enter Pensão Amor, in Pink Street’s main area (left image); and some tourists, locals (whites and blacks), and a few street sellers on the margins of Pink Street at the junction with São Paulo Street (right image) The two pictures were taken 5 minutes apart on 1st September 2019, around 2:30am. First author’s archive, 2019.

Until late 2012, the opening hours of nightlife venues in the city of Lisbon were regulated by both Decree-Law no. 48/96 of May 15th, and the Local Regulation on Opening Hours of Retail and Service Establishments in Lisbon (Resolution no. 87/AM/1997). Importantly, the expansion and commodification of nightlife in Cais do Sodré and the birth of Pink Street (Nofre, Martins, Vaz, Fina, Sequera and Vale, 2019) took place within this legal framework, which de facto allowed the existence of some almost 24-hour venues (e.g. Copenhagen and Europa discotheques with their after-hour parties). Similarly to the nearby Bairro Alto, which saw its first expansion of tourist-oriented nightlife in the late 1990s and early 2000s, residents’ protests in Cais do Sodré became very visible in the local public sphere with the creation of Aqui Mora Gente (People Live Here).

This informal online platform for residents was created with the aim of denouncing episodes of uncivilized behavior, noise in public spaces during nighttime hours and garbage on the street. The leaders of these informal platforms and some of their participants were local highly-skilled professionals who arrived in the neighborhood in the early 2000s (Nofre, Martins, Vaz, Fina, Sequera and Vale, 2019), when nighttime leisure was in decline, expecting to live by the riverside which was being transformed from its original use. As one of the middle-class residents participating in the focus groups in the SAFE!N project explained to us, “it seems [that] Lisbon City Council wants to use this kind of wild nightlife in order to push us to the limit so that we make the decision to leave the neighborhood”. However, her positioning is quite different from the (fewer) “older” residents, who argue that “[Cais do Sodré] has long been a place for sordid nightlife, with prostitutes, drunk sailors, and violence. It was part of the daily life of the area, but this is different, we cannot sleep and they [i.e. hundreds of patrons drinking on the street] do not respect the local residents”, as an elderly female in her seventies argued during an informal interview conducted on her street while she was going for an early-morning walk.

In response to the dramatic and critical worsening of community livability in Cais do Sodré and the nearby Bairro Alto quarter, the local administration approved a new regulation in 2012 relating to the opening hours for discotheques, dance bars, nightclubs and after-hour parties (Decree No. 100/P/2012, Lisbon Municipal Bulletin. No. 985, of January 3rd). The key goal was to avoid many dance bars working as after-hour venues. However, the regulation did not address the problems regarding the worsening of community livability in the nightlife district of Cais do Sodré, which are mostly derived from spatial-temporal concentration of partygoers in the quarter’s public spaces during nighttime hours on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays. In fact, the concentration of thousands of partygoers chatting, laughing loudly, screaming and singing hooligan-style during nighttime hours in the public spaces of Cais do Sodré is one of the key explanatory factors contributing to the rapid worsening of community livability in this quarter. In parallel to the massive use of public streets in this nightlife district of Lisbon, urine, rubbish on the ground, plastic cups, broken bottles, food leftovers and high noise levels in the public space during nighttime hours are -at the time of our fieldwork-much in evidence on the São Paulo Square, the main focus of the residents’ protests (see Figure 4 below).

Aforementioned Decree No. 100/P/2012 has proved to be totally ineffective. In December 2014, the local administration approved a New Opening Times Regulation for Nightlife Venues (Municipal Decree No. 140/P/2014). Article 5.6 deserves special attention, as it prevents any kind of nightlife venue from allowing customers to take away alcoholic drinks after 1:00a.m. However, our ethnographic fieldwork in the area allowed us to confirm the presence of a number of informal and financially precarious young street sellers (mainly of Asian origin, recently arrived in the city) who sell 1-euro beer from midnight until the early hours of the morning. Moreover, our ethnographic fieldwork also confirmed that many tiny traditional bars and tourist-oriented, middle class-oriented restaurants and Lounges in Cais do Sodré do not comply with current legislation, as they usually sell beer and other alcoholic drinks for take away after 1:00a.m. Indeed, the non-compliance of nightlife venues is a crucial element in the worsening community livability of Cais do Sodré. In October 2015, the local administration approved a new Local Regulation of Opening Hours on Retail and Service Establishments in Lisbon (Decree-Law 10/2015, of 16th January). This new regulation aimed to strengthen the regulation of opening hours by limiting those of nightlife venues but simultaneously facilitated the opening of new venues in the city center. However, and far from providing solutions, this new opening hours regulation worsened the community livability in the nightlife districts of Lisbon, such as the Bairro Alto (Nofre, Sánchez-Fuarros, Malet-Calvo, Martins, Pereira, Soares, Geraldes and López-Díaz, 2017) and Cais do Sodré (Nofre, Martins, Vaz, Fina, Sequera and Vale, 2019).

Resident protests in Cais do Sodré have continued to date due to the soaring touristification of Lisbon . It is worth mentioning here that the local administration recognizes that community livability during nighttime hours in the city’s nightlife spots such as Cais do Sodré has worsened, as the introductory section of the current regulation (Formal Notice No. No. 13367/2016) argues. According to the introduction, over the past two years, the local administration has recorded an increase in resident protests against noise caused by establishments (live music, loud chatting among patrons) and hundreds of consumers outside the establishments, “causing excessive noise in the public space” and discomfort that “is often associated with a number of pathologies, such as psychological disorders” and that also negatively affects “the quality of residents’ personal and family life”. For this reason, Formal Notice No. 13367/2016 introduces a set of amendments to the existing opening hours regulation, by creating a 24-hour open area (Zone A) on the city’s riverfront (former harbor area) and a wider area affecting the rest of the city where opening hours for nightlife venues are somehow limited. Despite this intent, “this new nighttime leisure space urges to be created” according to the Formal Notice’s introductory section. However, the fact that the current regulation fixes closing door times for venues in Zone B at 2:00am for bars, 4:00am for dance clubs, and 6:00am for discotheques on weekdays (with an extra hour on Fridays and Saturdays) clashes with residents’ ‘right to rest and/or sleep’, according to both Article 4 of the National General Regulation on Noise (Decree-Law 9/2007, of January 17th) and Articles 66.1 and 25.2 of the Portuguese Constitution, as well as according to a range of court orders released in recent years. None of the above has done anything to change such a conflictual context. In sum, in today’s Cais do Sodré, ‘the right to (neoliberal) leisure’ prevails over ‘the right to rest and/or sleep’.

Privatization and liminality of public space safety

The liminal governance regarding the regulation of opening hours for nightlife venues in Lisbon -which currently prioritizes the right to commodified, alcohol-fueled leisure over the constitutional right to rest and/or sleep- is also accompanied by limited law compliance regarding the exercise of private security at venues, with a particular emphasis on door access control. In 1986, the national administration imposed an obligatory psychological evaluation of private security workers and the obligation to be in possession of a professional ID card for security staff (Decree-Law 282/1986, of September 5th). However, a decade and a half later, the national administration reinforced a range of responsibilities for employees, business partners and the Portuguese national police itself (Decree-Law 34/2013 of May 16th). Among many others, these responsibilities were (i) the completion of an annual psychological evaluation for private security workers, (ii) the realization by the Portuguese national police of a complete exam for future private security workers to obtain an ID professional card, (iii) the creation of labor contracts for private security workers, and (iv) the continuous completion of professional training for employees. One year later, in 2014, the national administration approved Ordinance No. 148/2014 of July 18th that regulates mandatory professional training for private security workers. However, nothing that has been mentioned in this paragraph has been fully accomplished to date, as some informants (security staff and business partners) confirmed during our fieldwork.11 Moreover, in September 2014, the Portuguese government approved specific legislation on nightlife venue security staff (Decree-Law 135/2014, of September 8th), which aimed to promote safer environments not only inside nightlife venues but much more importantly in the public spaces near venue entrances. Importantly, in 1993, the then neoliberal government of Prime Minister Aníbal Cavaco Silva, who later became President of the Portuguese Republic under the troika regime, approved Decree-Law 276/1993 of August 10th, which saw private security forces become a subsidiary body of the police. This de facto meant the first privatization of public safety.

An ethnographic exploration of the in situ implementation of Decree-Law 135/2014 allowed us to collect crucial data for a comprehension of liminal nightlife governance in Cais do Sodré. On the one hand, the door staff who were working informally (even without a labor contract) at bars, dance bars, clubs and discotheques in the city’s nightlife spots until the entry into force of this last decree law were instantaneously (i.e. in less than 24 hours) transformed into professional private security workers wearing black-colored professional uniforms and even holding a professional ID card. On the other hand, the subsidiary role of the private security forces in relation to public safety (Decree-Law 276/1993) was reinforced because the aforementioned 2014 decree law gives full power to door staff to make use of legitimate violence to restore order in the public outdoor space surrounding the venue. However, the decree law does not delimit the frontier between the public space and the venue’s private space. Here, we find the second aspect of the liminality of nightlife governance in the urban night of Cais do Sodré, which has favored the rise of (sometimes violent) conflictual situations between partygoers and private security forces in the public space.

Final remarks

As stated in the introduction of this short research paper, many scholars have examined the social and spatial effects of the expansion of commodified nightlife in several cities across the developed world. However, to date, extraordinarily little has been said about the construction of the legal architecture through which the neoliberalization of the urban night operates in the field. The text has shown how the term «neoliberal nightlife» refers to not only the extreme commodification of nighttime leisure practices but (i) the modification of the nightlife-related legal framework to make ‘the right to party’ to prevail over ‘the right to rest and/or sleep’; and (ii) the exacerbation of exclusion, marginalization and criminalization of (non-white) working-class youth as well as of informal actors of the night (street vendors, aged sex workers, petty dealers, etc.).

In this sense, this article has examined this by taking the night in Cais do Sodré, in Lisbon’s downtown, as a case study. However, much more importantly, the study presented here has deepened our knowledge of what the ‘neoliberal night’ (e.g., Chatterton and Hollands, 2003; Roberts and Eldridge, 2012; Shaw, 2015; Nofre and Eldridge, 2018) means today and to what extent it is interrelated with the consolidation of the ‘tourist city’ as the main urban development paradigm in present-day southern European cities. In fact, very recent media reports have revealed that some traditional and iconic nightlife venues in Cais do Sodré have closed (e.g. the Oslo Bar), or are closing in the next 3 years (e.g. Sabotage, Jamaica, Europa, Tokyo, As Galegas, O Cantinho da Saudade, Solar da Ribeira, O Botequim da Ribeira and Agua de Beber) due to the construction of luxury hotels in the buildings where they are currently located. Moreover, new ongoing fieldwork has recently enabled us to confirm that ‘tourist massification’ of the night in Cais do Sodré has involved the spatial displacement of local partygoers to other (often peripheral) areas of the city that are (at least by now) not affected by tourism pressure.

Without a doubt, there is an urgent need to go beyond the economic approach to nightlife taken by not only the different local governments that have ruled the city over recent decades but also by the different supranational bodies, such as the European Commission. Even today, when nightlife is discussed in Europe (at local, national or supranational level), the discussion is mainly around licensing, regulation, crime, and culture-led strategies of urban regeneration and urban benchmarking, but nothing is said about the potential of nightlife as an efficient and sustainable mechanism of social wellbeing, cultural engagement and multicultural dialogue, community-building, inclusion, cohesion, identity, creativity and social innovation.

It is clear that there is an urgent need to move beyond the current liminal, neoliberal economic-centered conception of the urban night towards a new open, participatory, community-centered conception of nightlife governance. In the case of Lisbon, this new approach could emerge as crucial for the move towards a more inclusive and egalitarian nightlife in the Tourist City. In fact, nightlife can also be a time, space and source of inclusion, cohesion, multicultural understanding, and social wellbeing. However, despite the centrality of ‘culture’ to the European project and its societal value, little acknowledgement is made of the role nightlife and its spaces play in facilitating integration, cohesion, inclusion, community-building, belonging and social wellbeing. Academics, local actors and stakeholders must therefore go beyond the paradigm of the “24-hour economically productive city” and enhance the potential of nightlife as an efficient and sustainable mechanism of social wellbeing, inclusion, cohesion, multicultural dialogue and community-building in the EU in the 2020s and beyond. This is one of the greatest challenges for nightlife governance of our European cities in the future, with special importance for the recovery of post-COVID19 nights in Lisbon. We will develop this new research guideline in further articles.