Introduction

In 2016, the value of livestock production in Portugal represented M€ 2 630.9, with milk and beef representing 46.4% of this value. The Alentejo region holds 42% of cattle stock in Portugal (GPP, 2018) and the Portalegre district holds over one-quarter of the cattle farms in the Alentejo. Nowadays, animal welfare is critical in livestock production, not only because of its direct implications on productivity but also for consumers’ growing awareness of animal welfare and the sustainability of the food production chain. There is a close connection between welfare and health, and one of the most important measures of health status in cattle farms is the frequency of death, especially, of calves during their first 6 months of life (Ortiz-Pelaez et al., 2008). According to Mellor & Stafford (2004), the major factors predisposing newborn farm animals to death include hypothermia, maternal underfeeding, mismothering, infections, injuries and predation. Hypothermia can occur either from cold exposure or impaired heat production, the latter due to placental insufficiency, dystocia, immaturity at birth, among other factors (Mellor & Stafford, 2004). Such factors may affect cattle breeds differently, depending on their adaptation to environmental conditions and their inherent maternal capacities. Hence, the aim of this work was to obtain data regarding calf mortality in the progeny of the two most important native cattle breeds of the Alentejo region, the Alentejana and the Mertolenga, in the Portalegre district.

1. Review of literature

Alentejana and Mertolenga are the most representative native Portuguese cattle breeds (Bos taurus). They are raised mainly in rangeland conditions and used for industrial crosses with exotic breeds, mainly Charolais and Limousin (Pereira et al., 2008). Alentejana has historically been the major breed of cattle raised in southern Portugal and has recovered from a strong census decline in the mid-20th century (Carolino & Gama, 2008). Originally bred as a working breed, from the 1970s onward the breeding goal has evolved for meat production, improving its growth and adult weight (ANIDOP, 2019). Mertolenga is a local cattle breed raised under typical low input range conditions of Southern Portugal, with hardiness, low maintenance requirements, easy calving and high fertility as main attributes (Matos et al., 2002).

Calf survival from birth to weaning is an important measure of the performance of a beef cattle breeding herd (Hickson et al., 2016). Several factors determine calf survival, including genetic type, cow milk production, calf management, and environmental conditions, among others (Daza Andrada, 2018).

Maternal factors are critical to neonatal survival at several levels. Dystocia is associated with important economic losses due to an increased number of stillbirth, maternal injury and calf mortality. The factors that influence the prevalence of dystocia include infection, heredity, nutrition, calf sex, exercise, cow age and gestation length (Mekonnen & Moges, 2016). Recent studies in beef cattle breeds confirm that calving difficulty is a heritable trait and that it is highly correlated with calf birth weight and gestation length (Jeyaruban et al., 2016). Inadequate maternal size at first calving is a risk factor for dystocia (Holmøy et al., 2017), hence the need to consider ease of calving when choosing bulls or semen and also to monitor body condition in beef heifers. Moreover, subclinical trauma in newborn calves has been associated with calving difficulty, decreased vigor and decreased odds of having an adequate transfer of passive immunity, increasing mortality and morbidity risks (Pearson et al., 2019).

Another maternal factor than can interfere with calf survival is milk production and, in an early phase of the suckling period, udder conformation. Studies that compared udder conformation in different cattle breed-crosses concluded that more outward-pointing teats were associated with an easier consumption of colostrum and, hence, with an improved immune status of calves and lower mortality rates (Hickson, et al., 2016). Total milk yield in beef cows depends on the parity and the age of the cow at first calving but can also depend on the adaptive ability of cows to allocate energy to different functions, which in turn varies with breed and milk potential (Cortés-Lacruz, et al., 2017).

Maternal behavior is another crucial factor to calf survival, and directly connected to the establishment of the dam-calf relationship in the first hour’s post-birth, transfer of passive immunity through colostrum, adequate milk ingestion by the calf and active protection of the calf against eventual predators and other threats. Maternal behavior has shown low to moderate heritability, ranging from 6% to 42% (Costa, et al., 2018). Low heritability expresses the important influence of environmental factors, such as cow and calf management. Nevertheless, there are differences in maternal behavior heritability between beef cattle breeds (for instance, 13.5% in Blonde d’Aquitaine vs. 10.8% in Limousin), and maternal behavior shows moderate to high genetic correlations with udder swelling and milk yield (Michenet et al., & Phocas, 2016).

2. Methods

This study is a retroactive cohort regarding calf mortality from birth to 180 days in the offspring of Alentejana and Mertolenga dams in the Portalegre district (Alentejo region, Portugal) between 2016 and 2018.

2.1 Sample and data collection

From consultation to the National System of Animal Registration and Identification (SNIRA) database, we retrieved data regarding registers for cattle births in the Portalegre district, from 1st January 2016 to 31st December 2018. Records included birth date and breed of the dam, location of the farm (municipality in the Portalegre district) and the date of calf deaths between birth and 180 days. This allowed us to divide calf death records according to specific periods: perinatal (from birth to 2 days); from 3 to 30 days; and from 31 to 180 days. The number of adult females (over 20 months) for each farm was also obtained.

2.2. Statistical analysis

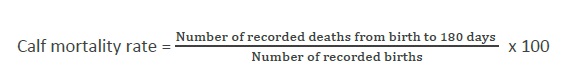

Overall calf mortality rates and mortality rates for calves born from Alentejana and Mertolenga dams were calculated as follows:

For calves born from Alentejana and Mertolenga breeds, the mortality rate from 0 to 2 days, from 3 to 30 days and from 31 to 180 days were also calculated.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the average number of adult cows per farm in each municipality and calf mortality rates, for both breeds were obtained. Finally, a two-way analysis of variance including dam’s breed and calf death age range as independent variables and age of dam as the dependent variable was performed, followed by Duncan’s multiple range test for post hoc analysis. Data are presented as estimated marginal mean ± standard error (mean ± S.E.). A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical procedures were performed using IBM SPSS for Windows, v. 25 (IBM Corp., 2017).

3. Results

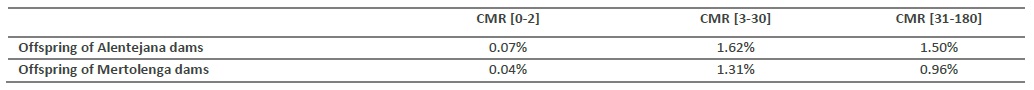

3.1 The overall number of calf births and deaths until 180 days in the Portalegre district

During the 3 years period 230 705 calf births were recorded in the Portalegre district, of which 26 871 (11.6%) born from Alentejana dams, and 6 790 (2.9%) born from Mertolenga dams. A total of 13 563 calf deaths between birth and 180 days were recorded in the same period, of which 856 and 157 corresponded to calves born from Alentejana and Mertolenga dams, respectively. The calf mortality rate in the Portalegre district during the 3 years period was 5.9%. The calf mortality rate for the offspring of Alentejana dams was 3.19% and for the offspring of Mertolenga dams was 2.31%. Mortality rates from 0 to 2 days, 3 to 30 days and 31 to 180 days in offspring of both breeds are shown in table 1.

3.2 Effect of the average number of adult cows per farm on calf mortality

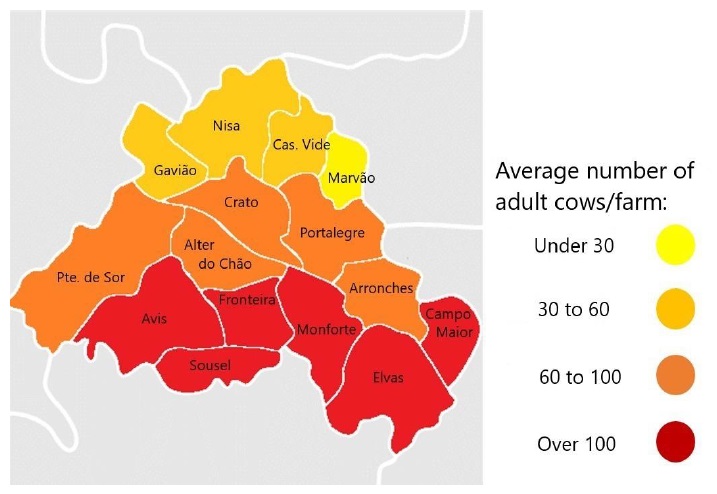

The average number of adult females (all cohabitant breeds) per farm in each municipality of the Portalegre district was calculated, and municipalities were then classified according to these values in 4 classes, according to figure 1.

Figure 1 The average number of adult females per farm in the municipalities of the Portalegre district.

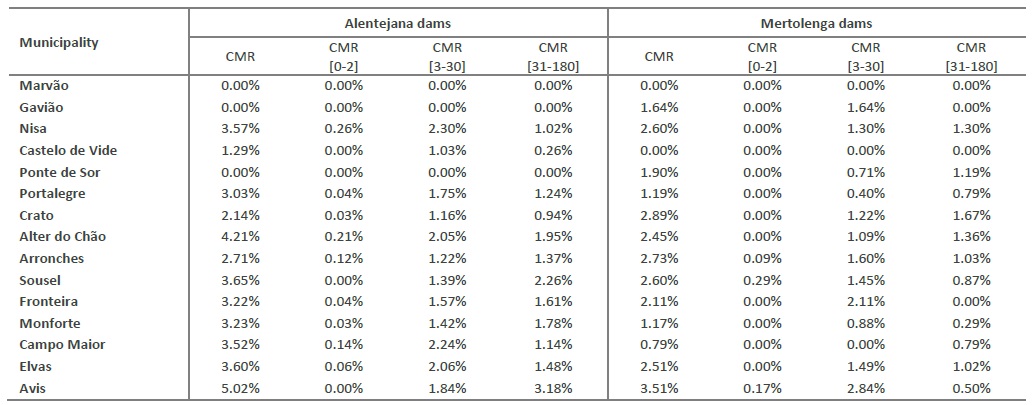

Table 2 presents the mortality rates of calves born from Alentejana and Mertolenga dams in each municipality of the Portalegre district from 2016 to 2018, in ascending order of the average number of adult females per farm in each municipality. The municipality of Marvão (the one with the lowest number of adult females per farm) showed no calf mortality up to 180 days in either breed during this period. On the other hand, the municipality of Avis (the one with the highest number of adult females per farm) showed the higher mortality rates, for both the Alentejana and the Mertolenga breeds (5.02% and 3.51%, respectively). The municipality of Alter do Chão presented the higher calf mortality rate between 0 and 2 days (CMR[0-2]) in the Alentejana breed (0.21%), while Sousel showed the higher CMR[0-2] in the Mertolenga breed (0.29%). The higher values of calf mortality between 3 and 30 days (CMR[3-30]) were in Nisa, for the Alentejana dams (2.30%) and in Avis, for the Mertolenga dams (2.84%). Finally, maximum values for calf mortality between 31 and 180 days (CMR[31-180]) were found in Avis (3.18%) and Crato (1.67%) for Alentejana and Mertolenga dams, respectively.

Table 2 Calf mortality rates of Alentejana and Mertolenga dams in the municipalities of the Portalegre district from 2016 to 2018.

Obs: CMR - calf mortality rate (overall, 0 to 2 days, 3 to 30 days and 31 to 180 days).

Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the average number of adult cows per farm (AAC) and the average calf mortality rates (CMR) in the Portalegre district, for the offspring of Alentejana and Mertolenga dams, were calculated. CMR, CMR[3-30]) and CMR[31-180] were positively correlated with AAC in the Alentejana breed (r=0.75; p = 0.00148), but not in the Mertolenga breed.

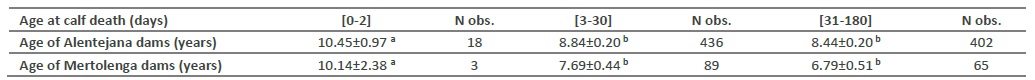

3.3 Association between the calf mortality age range and the breed and age of the dam

The average age of Alentejana and Mertolenga dams in the Portalegre district was 8.22±3.61 and 8.04±3.85 years, respectively. The average age of Alentejana and Mertolenga dams whose calves died between birth and 180 days was 8.68±4.03 and 7.37±4.50 years, respectively. The age of the dam had a significant effect on the age range of calf mortality (p = 0.024). The age of dams in the calf mortality between 0 and 2 days (10.41±2.98 years) was significantly higher than in the other two categories (8.64±4.34 and 8.21±3.91 years for calf mortality from 3 to 30 days and from 31 to 180 days, respectively; p=0.024). The breed of the dam (Alentejana or Mertolenga) showed no significant effect on the model. Table 3 shows the age of Alentejana and Mertolenga dams according to the different periods of calf mortality.

4. Discussion

The age of the dam, gestation length, the sex and weight of the calf, the season and herd size, have been previously reported to affect perinatal mortality and there were significant interactions between breed and other risk factors of mortality (Bleul, 2011). It was suggested that the identification of breed-specific risk factors of perinatal and postnatal mortality could help to develop strategies to improve the problem.

The Portalegre district’s orography shows a distinct difference between the mountainous Northern areas (such as Marvão and Castelo de Vide), with typically smaller farms, and the Southern areas (such as Monforte and Elvas), where plains and larger farms are predominant. This geography influences the average herd size in the different municipalities, with smaller herds concentrating in the Northern, more mountainous municipalities. Herd size can influence calf mortality due to increased pathogen concentration in larger herds, and a need for a larger human resource availability to assure birth and calf management during calving season (Bleul, 2011). These factors may explain the differences in calf mortality rates found among the municipalities of Portalegre district.

A definition of perinatal mortality is the death of the perinate calf prior to, during or within 48 hours of calving, following a gestation period of at least 260 days, irrespective of the cause of death or the circumstances related to calving (Mee, 2013). Recent studies show that the main causes of perinatal death in beef cattle are dystocia related, namely anoxia and trauma (Norquay, 2018). The genotype of the dam also plays a role in determining the risk of dystocia; the maternal ability of the dam to nurture the fetus influences birth weight, and the dam's genetic potential for growth influences the size of her pelvic area (Hickson et al., 2006). Recently, an association between single nucleotide polymorphisms in the leptin gene and bovine perinatal mortality has been discovered (Mee, 2013). Regarding the dam’s age, there is evidence of a higher calf mortality rate in heifers (calving under 3 years of age), but also in cows older than 10 years of age (Elghafghuf et al., 2014). Our data show that average dam’s age was significantly higher in calves that died before 48 hours of birth, regardless of breed, apparently showing a higher risk for dams over 10 years of age.

As has been previously stated, indigenous Alentejana and Mertolenga cows are often used as dams for crossbreeding in the Alentejo region, with Limousin and Charolais bulls being the most used. Ease of birth is directly related to calf-dam proportionality, with a higher size and birth weight of the calf constituting a risk factor of dystocia. In a study that addressed calf mortality in crossbreds of Retinta (a Spanish indigenous breed, very similar to Alentejana) and Charolais and Limousin, the use of bulls of the former breed increased the incidence of dystocia, when compared to the latter (Daza Andrada, 2018).

Calf mortality before weaning in beef cattle has its higher risk period between 4 and 10 days of age, and the most common causes of death are metabolic and digestive disorders (Mötus et al., 2018). The results of this study are consistent with this, since higher mortality rates were found between 3 and 30 days for both breeds.

The overall calf mortality rate in the Portalegre district during the study period (5.9%) lies in the range of previously reported rates (Mötus et al., 2018; Todd et al., 2018). Our results show that the offspring of both indigenous breeds (Alentejana and Mertolenga) showed considerably lower mortality rates, particularly in the case of the offspring of Mertolenga dams. Despite this breed’s small size, ease of birth has always been a recognized character of the Mertolenga breed, along with high fertility rates and rusticity (Rodrigues, 1981). We can probably attribute the lower calf mortality rates of these indigenous breeds (when assessed under the same production system and environmental conditions as other stock) to genetic factors. Further studies should therefore be developed to better understand and quantify the genetic effects that influence calf mortality in indigenous breeds.

Conclusions

Calf mortality in the Alentejo district shows overall values that agree with others found in literature. In this study, there was an apparent relationship between herd size and calf mortality rates, also in accordance with previous works. Perinatal calf mortality showed a significant association with average age of dams, which was higher than for the other calf mortality age classes. The mortality rates for the offspring of Alentejana and Mertolenga dams were lower than the average mortality rate, even though most of these dams are used for terminal crossbreeding with improved beef cattle breeds. Considering calf mortality is being increasingly regarded as a reliable indicator of cattle welfare, further work on the genetic factors that may explain these differences should be developed, as means of adding value and contributing to the conservation of autochthonous beef cattle breeds.