Introduction

Given the importance and potential usefulness of qualitative research to provide answers to problems that arise in professional practice in various fields of knowledge, the need for investment in teaching the qualitative method is evident, both in undergraduate and postgraduate courses. Qualitative research has received increasing attention in developed and developing countries. However, a difficulty in teaching it in an academic environment governed by quantitative norms (Taquette & Borges, 2019) has been identified. Moreover, there is extensive heterogeneity in the courses, which somewhat reflects the conceptual polysemy of qualitative research and the multiple investigation techniques, collection instruments, and theoretical bases for data analysis.

In the absence of specific training, researchers often do not use or use the tools of a qualitative nature with less rigor, and, therefore, have more difficulty in developing consistent research. Generally, the concerns and questions that arise for beginners in the practice of qualitative research are due to the lack of ontological and epistemological understanding of scientific knowledge. Professionals trained within quantitative logic are often unaware of the qualitative method and do not value it, questioning its scientificity (Schraiber, 2017). This is observed, for example, with medical researchers, whose training is predominantly technical with hardly any human science content. Students are technically prepared to treat diseases, including those of high complexity, but have difficulty looking at the patient within their historical, social, psychological, and biological context (Castro, Fontanella & Turato, 2011). This type of training impedes the development of qualitative health studies that require interaction between people and contextualize the problems that arise (Taquette, Minayo & Rodrigues, 2015)).

According to Barros (2011), it is necessary to expand and diversify the techniques and methods of teaching social sciences to health professionals to give more clarity to the social perspective of the health-disease-care process. The existing teaching models of social sciences do not seem to be sufficient for a more comprehensive understanding of health events. In a previous review on the teaching of social sciences in medical schools, Nunes (2003) found great thematic diversity in their content. In general, the teaching of these sciences is performed in the pre-clinical years of the course, unlinked from practice, not allowing students to have a more reflective training that enables them to understand health in a socio-historical context.

In a virtual debate between five Iberian-American researchers, professors of qualitative methodology from different countries and backgrounds showed that there is great enthusiasm in learning qualitative research, mainly by young people and women. However, they found that teaching programs are not fully developed, and the academic environment is not yet favorable to learning research of this nature. They concluded that there is interest in the qualitative method, but few advances have been observed in expanding and qualifying the use of the method (Mercado, Bosi, Robles, Wiessenfeld & Pla, 2005). Bosi (2012) advocates the view that we must face several challenges in the epistemic and operational field to achieve the consolidation of qualitative research.

According to Portuguese educator Amado (2010), teaching the qualitative method must include the epistemological and theoretical foundations of the human sciences, the research strategies, and data collection techniques, the data analysis procedures, their validation, and presentation. The author considers that a qualitative investigation must be systematic, based on theoretical principles and ethical attitudes, carried out by informed and trained individuals. The effective teaching-learning of the qualitative method implies training students capable of gaining autonomy to develop quality studies, with ethics and social responsibility, inserted in their reality. To this end, the constructivist perspective of teaching is adequate, as it requires the active participation of the student in the learning process before problem situations, where new information is integrated with previous experiences for the construction of new knowledge (Freire, 1970; Amado, 2010). The constructivist pedagogical proposal expands the possibilities of doing science through the collective effort to understand reality, to interpret human facts, to build theories that help this understanding. As a result, individuals can, thus, think critically about the world independently and make decisions with autonomy in different contexts. Teaching should not be restricted to the teacher-student information transfer. Amado (2010) points out that some people find it easier or harder to do qualitative research and that some prerequisites are necessary, such as being open and willing to reflect on themselves and their actions, ability to interpret, tolerance to ambiguity, ability to address conflicts, creativity, patience, and persistence, which can be achieved with research experience and professional maturity.

In a symposium on teaching qualitative methods in Berlin in 2006, Breuer & Schreier highlighted the difficulties faced by qualitative researchers within their institutions. Their research is seen as of secondary importance and also evidences underappreciation for the work developed. These authors allege that, for some, the qualitative method would only serve for the first insights on the research topic and then be “really researched” quantitatively through the hypothesis test.

According to Herzog (2008), several aspects influence the value that is given to teaching the method, such as, for example, the area of knowledge in which it is taught, the type of organization, whether university or isolated college, the target audience, and whether undergraduate or postgraduate. Another factor pointed out was the learning context, which may vary if the discipline is optional or mandatory, and also by type of learning assessment. Furthermore, the available scientific literature on the teaching-learning of qualitative research methods appears to be insufficient.

Breuer & Schreier (2007) believe that the teaching models of qualitative research alternate between two poles, one marked by a paradigmatic and holistic conception, in which the theoretical foundations that support science are discussed, and the other, predominantly pragmatic, based on research practices and techniques. These different concepts imply different assumptions regarding the teaching and learning processes. The first paradigmatic pole is linked to theories of constructivist learning and the perception of qualitative research as a craft that is learned above all in the context of joint research activities. On the other hand, the pragmatic pole suggests that qualitative methods are understood as techniques and that the acquisition of knowledge about these techniques does not necessarily imply the participation of students in the learning process. Herzog (2008) opposes those who consider teaching the method as a technique or art and highlights the main points of teaching the method: the social context of learning, epistemological models, the specific, educational experiences of qualitative research, the teacher’s role and his personal experience with qualitative methods.

Qualitative research proves to be useful and relevant in several fields of knowledge, as it can provide answers to questions that inductive methods cannot. In the health area, for example, quantitative approaches have been used to know the causes and effects and the effects of diseases, and allow generalization of the findings, but are unable to explain why different social contexts and perspectives interfere with falling ill. On the other hand, a qualitative approach allows understanding why two people with the same disease react differently to treatment (Taquette & Borges, 2020). It studies the facts in their natural environments and seeks to interpret phenomena concerning the meanings people bring to them (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018). Given the evidence of the relevance of qualitative research and its plurality of procedures, the question arises as to how it is being taught. In search of an answer to this question, this study aimed to raise questions and information relevant to the teaching of the qualitative research method through the bibliographic review of scientific papers. It is hoped that its results will support pedagogical proposals that expand and qualify the use of the qualitative method in scientific research.

1. Methods

1.1 Study type

A bibliographic review was carried out with a documentary analysis of scientific papers published in indexed journals that address the theme “teaching the qualitative research method”. A literature review on the subject was made in the SciELO and Medline databases and 15 titles were selected from three major areas of knowledge: Health Sciences, Humanities and Social and Applied Sciences. Data thematic analysis originated 3 categories: course modalities, pedagogical strategies and problematization of the method use / teaching.

1.2 Procedures

The search for titles was carried out in the Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) database in Brazil, the main database of Brazilian scientific journals from all areas of knowledge, whose papers accepted for publication are evaluated by peers with previously established criteria and validated by the scientific community. Then the search was done on Medline (PubMed), the most relevant and complete international database of scientific journals in the health area. There bibliographic search had no time limit. Papers were searched for all years until March 21, 2019. The central theme of the paper was teaching the qualitative method and being available in Portuguese, Spanish, or English. The exclusion criterion was the non-availability of the full-text paper.

In SciELO, the descriptor “qualitative method” was initially used, which gave rise to eight works, none of which dealt with teaching the method. The second attempt was with descriptor “qualitative research”, which returned 847 publications. A new search was made adding descriptor “teaching”, reducing the number to 67 publications. Of these, after reading the titles, only seven publications on the subject of the study, teaching the qualitative method, were selected. The third and last attempt was with the descriptor “teaching the method”, which returned one paper. Therefore, eight works from the SciELO database were read and analyzed.

On the PubMed website, the search was carried out by the Mesh Database with descriptors “qualitative research” AND “teaching methods”, giving rise to 34 publications. Seven papers were selected after reading the titles. All were in English.

The thematic analysis of the papers was performed by reading and rereading to familiarize with data and have an idea of the whole. Then we identified the main themes, considering the study objectives. Finally, encoding, classification into categories and a comprehensive analysis of the themes were performed, with the elaboration of an interpretative synthesis. The reading, encoding, and categorization phase were carried out separately by two researchers: the author, from the area of Health, and another researcher, from the area of Engineering. The comparative, comprehensive, and interpretative analysis was done by both together.

2. Results

The 15 selected titles, eight collected in the SciELO database, and seven in PubMed are shown below in Table 1, containing the authors, year and place of publication, study design, objectives, area of knowledge, and main results/conclusions.

The titles found in SciELO stem from three significant areas of knowledge, namely, Health Sciences, Humanities, and Social and Applied Sciences. Health was covered with three papers in the field of Medicine. Humanities had three papers, two from Sociology and one from the Education area, and Social and Applied with two papers from the Administration area. In PubMed, six papers are from the main area of Health Sciences, five from the Nursing area and one from Medicine, and one paper in Social Sciences, for the Social Work area. Thus, in the total of the two bases, the following were selected by main area: Health Sciences (9, five Nursing and four Medicine); Human Sciences (3, two Sociology, and one Education); Social and Applied Sciences (3, two Administration and one Social Service).

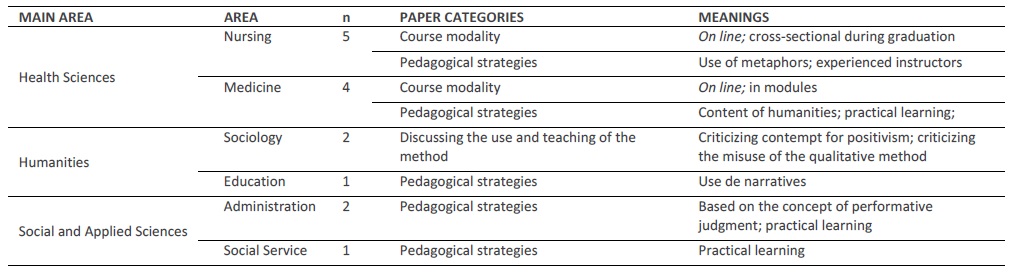

As for the type of study presented in the works, the most frequent paper category was experience report, with six papers and, the second, essay, with five titles. Three papers refer to qualitative studies and one editorial of a journal on qualitative research. Regarding the study location, six of them were developed in Brazil and four in the U.S. The remaining five were conducted in the United Kingdom, Spain, Israel, Canada, and Mexico. The papers initially classified by area of knowledge were categorized after analysis by meanings that emerged from reading, as described in table 2 below:

3. Discussion

Health sciences

The nine papers analyzed were from Nursing (5) and Medicine (4). They were classified in the categories “course modalities” and “pedagogical strategies”. Regarding the course modalities, Ariel, Tamir & Man (2015) present a discipline incorporated into the initial years of undergraduate Nursing course before contact with the clinic. The course includes an introduction to Sociology and Anthropology in health, so that students familiarize themselves with central sociological paradigms, including the interpretive-constructivist paradigm that constitutes a basis for qualitative research, and also with sociological issues relevant to the clinical field, and the subjective personal and cultural meaning of disease situations. The practical internship starts with learning observation and in-depth interviews and extends to the end of the course. Another modality presented by Nursing was an online course, and the authors affirm it is useful to understand qualitative research intricacies (Holslander, Racine, Furniss, Burles & Turner, 2012). Of the four Medicine papers, two studies discuss relevant points of being included in methodology courses to ensure proper learning, and two present an evaluation of teaching modalities. In a qualitative research conducted through in-depth interviews with medical researchers, Taquette et al. (2015) found that most of the respondents considered it necessary to include humanities content in the medical curriculum and teaching the method practically, through participation in research and presentation of inputs of these studies to the health field. In the same vein, in an essay on a proposal to teach the qualitative research method to psychiatrists, Whitley (2009) draws attention to the importance of showing the student qualitative investigations with significant contributions to health. Calderón (2012) reports the experience of distance teaching the qualitative method to health professionals in the primary care network, with good acceptance by the participants. The course has eight teaching units, starting with the theoretical aspects, then learning the techniques, and, finally, the data analysis and presentation. Another positive evaluation is presented by Mercado-Martínez, Tejada-Tayabas, Alcántara-Hernández, Mercado-Marínez, Fuentes-Uribe & Trigueros-Becerral (2008) in a qualitative study developed to assess a course on methods for health professionals taught in six monthly modules addressing themes similar to those of Calderón (2012).

In the category “teaching and learning enabling strategies”, in an experience report, Cook & Gordon (2004) suggest the use of analogies and metaphors in the teaching of qualitative research, as they can be used to enable and deepen understanding, allowing students to expand the ways of visualizing the concepts under study, so that they may establish creative and imaginative links between existing conceptual structures and those associated with new knowledge. They are potentially rich and useful as teaching and learning strategies. In an editorial paper in the Qualitative Health Research journal, Morse (2005) highlights that it is necessary to take care of teaching the method to promote qualitative research. The same can be done in several ways, with an experienced instructor helping the student by using his own research experience. This subtopic is also treated by McAllister & Rowe (2003) in a paper in which they suggest teaching in four phases: development of the qualitative view, involvement in field activities; preparation for data collection; and preparation for data analysis and interpretation. The authors point out that the practical research knowledge of skilled teachers facilitates students’ understanding of research theories and techniques and can promote an advance in the quality of education and, consequently, in qualitative research.

Humanities

Of the three titles analyzed, two are in the field of Sociology classified under the category “discussing the method”, and one in Education, classified under the category “teaching strategies”. Sociology papers are critical essays by social scientists, experienced authors such as researchers and professors of higher education, regarding the use and teaching of the qualitative method (Cano, 2012; Minayo, 2012). The authors converge and diverge on several points. Both discuss the teaching-learning of the qualitative method, but Cano (2012) addresses social scientists, and Minayo, health professionals. Cano criticizes the hegemonic positioning within the Social Sciences in favor of qualitative research and the false qualitative and quantitative dichotomy. He says that most of the scientists critical of positivist science struggle in developing empirical research, and in articulating theories with practice. In this environment, only the great classics such as Durkheim, Weber, and Marx are valued, leaving aside the social micro theories that are used in particular situations. The author advocates for the teaching of research methodology with rigor, and the valorization of both qualitative and quantitative approaches. On the other hand, Minayo affirms that the classic authors of social macro theories have their rightful place, but it is necessary to advance in the deepening and broadening of their questionings regarding social dynamics. New concepts emerge in the face of new realities and social circumstances. The author (Minayo, 2012) points out that it is challenging for social scientists to understand the biomedical logic of health, which hinders the dialogue between these areas. On the other hand, the author emphasizes that the teaching of Social Sciences in health courses, when they exist, are weak and hardly valued. Despite the recognition of the social role in illness, the biomedical logic still prevails in health education, and there is an amateurism in Social Sciences in the field of Health, and professionals from other areas frequently teach and guide students on social topics uncritically and instrumentally.

The title of the Education area analyzed is an essay in which the author advocates the use of narratives as an educational tool, both in teaching and research (Cunha, 1997). She believes that the narrative causes changes in the way people understand themselves and others. She highlights the dialectical relationship that is established between narrative and experience. Just as experience produces discourse, the latter also produces experience. There is a dialectical process in this relationship that causes mutual influences. Therefore, this suggests that the perception and production of narratives serve both as a research procedure and a training alternative. They allow the unraveling of elements that are incomprehensible by the narrator himself, who, many times, had never been encouraged to express his/her thoughts in an organized fashion.

Social and applied sciences

Two titles from the Administration area and one from the Social Service area were analyzed, all classified in the “teaching strategies” category. Bispo’s paper (2007) is an essay in which the author suggests a qualitative research discipline proposal to Ph.D. students in Administration based on the concept of performative judgment that implies intellectual autonomy to address the intricacy of research through knowledge of techniques, the ability to make decisions and solve research problems. It also involves understanding the origins of scientific knowledge and the management of research theories and methods. The other title is a qualitative study conducted with postgraduate students in Business Administration to understand how master’s students learn to conduct qualitative research. Four students participated in a research project, were observed and interviewed during the process. The authors concluded that participation in the research expanded the teaching-learning of the method and highlighted the need for teachers to review their practices and for managers to support teacher training programs concerning didactic-pedagogical policies (Villardi and Vergara, 2011). The only title in the area of Social Work describes an experience report of a pilot study of teaching the qualitative method through the practice of field research with older adults, positively evaluated by the authors of the work (Sidell, 2007).

In summary, the papers move into three major categories: 1- Course modalities: distance learning, with modules, and cross-sectional throughout the graduation; 2- Teaching strategies: Humanities content, use of metaphors, use of narratives, associated with practical research activities, use of evidence of contributions of qualitative studies and experienced instructors; and 3- Discussing the qualitative method: criticisms of social scientists to the quantitative, difficulty of integration and dialogue between the social sciences and other areas of knowledge, and misuse of the qualitative method. In general, the paper contents show the difficulty of having a qualitative method teaching standard, given its subjectivity that is inherent to its object of research, the human being, and its relationship with the researcher.

Conclusions

The lack of studies on teaching-learning of the qualitative method, as well as diversity between the experiences presented, show that it has not yet been consolidated, compared to other hegemonic research methods. The need and urgency to expand the teaching of the qualitative method so that it is more used, recognized as indispensable for science, and incorporated as mandatory in related graduate programs is evident.

Some points are highly relevant to a teaching-learning method proposal in the various areas of knowledge as follows: the constructivist model of teaching, teaching-learning not restricted to research techniques, and practical teaching-learning. Therefore, the paradigmatic conception of teaching, which discusses the theoretical foundations that underpin science, seems to be the one with the highest potential to achieve educational objectives. Among these objectives, we highlight the epistemological understanding of what science is, the knowledge of the logic underlying qualitative research; the ability to use the various data production techniques in qualitative research; the ability to analyze research results rigorously; and competence in preparing study reports.

Finally, we should emphasize the limitations of this study, whose bibliographic review was restricted to two databases, with a predominance of studies in the Main Area of Health Sciences. However, we believe that the issues raised may be useful to other areas of knowledge where qualitative investigations have their rightful place.