Introduction

In an era of increasing environmental problems, the sustainability of tourism, particularly in rural tourism, is now of central importance. Sustainable tourism should make optimal use of natural and environmental resources, respect the socio-cultural authenticity of host communities and provide socio-economic benefits to all stakeholders (UNWTO, 2019). This is important because a good part of the market tends to look for an environmentally friendly and socially responsible destination (Penz, Hofmann, & Hartl, 2017; Pulido-Fernández & López-Sánchez, 2016). Indeed, travel trends report for 2019 highlight, among others, that i) ecological tours are in demand, ii) tourists seek local experiences, iii) tourists seek history and culture (Mittiga, Silva, Wernet, Kow, & Kutschera, 2018).

Travel trends report for 2019 also emphasizes that the travel industry is continuously transforming as new technology is designed and developed - tourist suppliers need to step up to ensure that they don´t feel behind. The majority of the travelers are comfortable researching, booking and planning their entire trip to a new travel destination and prefer to find out on their own the necessary information for their trip (Mittiga et al., 2018).

Among the most successful marketing strategies in the tourism market is “growth hacking”, or the set of techniques which, through the minimum expenditure and effort possible, try to create a continuous increase in the attraction of tourists and company visibility and notoriety. This is even more important in a context of scarce resources typical of rural areas (Pato, 2019a; Pato & Kastenholz, 2017), notably in the most peripheral and lagging ones. Here, small business units of tourism need to use the more efficient and less expensive ways to communicate with the market.

Hence, information and communication technologies (ICTs) are fundamental for small business units of tourism for three major questions: i) they can improve the promotion of business’s philosophy to a growing and distant market, ii) they offer the potential to make information and booking facilities available to large number and distant tourists at relatively low costs (Hojeghan & Esfangareh, 2011) and, iii) they are more sustainable tools of advertising and promotion (such as flyers). A bit everywhere rural tourism suppliers and e-commerce companies are aware of this reality and need, trying to skillfully communicate their respective sustainable tourism offer (Biosphere, 2019a).

Although the study of sustainable tourism is extensively explored in the literature, to the best of our knowledge, research concerning the link between sustainable rural tourism and ICT is sub-explored in tourism literature. Furthermore, there is only a very limited empirical evidence on which ICT affect the performance of rural tourism (Sedmak, Planinc, Kociper, & Planinc, 2016), particularly in Portugal.

Given the importance of sustainable strategies and ICT for rural tourism in service delivery and promotion (Peña, Jamilena, Ángel, & Molina, 2013), its fundamental to explore more about this relationship. This constitutes the sphere of study of the present work, which explores the importance of eco-labels certifications and ICT in one of the rural tourism units located in Viseu Dão-Lafões Region (VDLR). We choose VDLR because is one interior region of Portugal where tourism can play an important role in order to improve economic diversification. Then, we opted to study a particular unit because is one of the few or the only rural tourism enterprise in the region to get two sustainable certifications (Green Key and Biosphere).

The paper is structured as follows: apart of the introduction, we provide the literature review covering the two key areas of the study: sustainability and ICT. The methodology and the case study are then, presented in section 2. In section 3, we present the main results of the study. We conclude by summarising the study´s main conclusions and highlighting its limitations, as well as proposing possible areas for future research.

1. Literature review

1.1 The Sustainability of rural tourism and challenges

Sustainability issues have gained remarkable attention in recent decades. The Bruntdland report, also known as "Our Common Future", nevertheless marks one of the milestones in terms of sustainable development. In this report the World Commission on Environment presented a new look at sustainable development, defining it as "development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs" (UN, 1987, p. 43). The report emphasizes the need for a relationship between the human being and the more harmonious environment. From here, the concept gains dimension and is emphasized. Successive World Conferences on Sustainable Development (also known as Summits of the Earth) are a good example of this.

Concerning tourism, given the commonly negative impacts of the activity (Mathieson & Wall, 1982), particularly in the so called "mass tourism", the issue of sustainability is nowadays particularly relevant. Sustainable tourism sees tourism within destination areas as a triangular relationship between host areas and their habitats and peoples, holidaymakers, and the tourism industry (Lane, 1994). It aims to minimise environmental and cultural damage, optimise visitor satisfaction and maximise long-term economic growth of the region and suppliers (Lane, 1994). As referred in the seminal work of Lane (1994) sustainable tourism is a tool for conservation and development. The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO, 2019) also shares this purpose, which express that sustainable tourism should:

make optimal use of natural/environmental resources that constitute a key element in tourism development, and conserve natural heritage and biodiversity;

respect the socio-cultural authenticity of host communities; conserve their built and living cultural heritage and traditional values;

ensure viable and long-term economic operations, providing socio-economic benefits to all stakeholders that are fairly distributed, including stable employment and income-earning opportunities and social services to host communities.

If tourism is an agent of development of rural areas (Kastenholz, 2014; Pato, 2012) it is very important conduct the activity in a sustainable way. This because it is very easy to damage the rural environment - repository of natural, cultural and historical heritage. If rural areas lose these primary resources also lose their attractiveness. Customers look for high quality and unspoiled scenery, for peace, quiet, personal attention in the rural environment (Lane, 1994; Pesonen & Komppula, 2010), that is the “rural idyllic” or nostalgic rural (Figueiredo, 2013), which small-scale tourism units can offer to their guests. This means that responsible and sustainable tourism in rural areas considers development that meets the needs of current tourists and all stakeholders in tourism (including host communities), while preserving and enhancing the potential for the use of tourist resources in the future without reduce the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Angelkovaa, Koteskia, Jakovleva, & Mitrevskaa, 2012).

In order to provide and guarantee memorable and sustainable experiences toward tourists some rural tourism enterprises (RTEs) have now the possibility to be sustainable certificate.

For its notoriety, we emphasize here the Biosphere certification and Green Key certification. The Biosphere certification which is supported by Unesco intends to guarantee an adequate long-term balance between the economic, socio-cultural and environmental dimensions of a destination/business, reporting significant benefits for a tourism entity, society and the environment (Biosphere, 2019b). Green Key is a voluntary eco-label awarded to more than 3000 hotels and other establishments in 57 countries - it is the leading standard for excellence in the field of environmental responsibility and sustainable procedures in tourism industry (GreenKey, 2019b).

1.2 The importance of ICT in the promotion of sustainable rural tourism

Communication in the tourist industry acquires special relevance, since the tourist product lives on the image that is create and the tourist product is often distant from consumers (Pato, 2019a). These consumers are increasingly independent and rigorous with tourist destinations and are more active in the search and dissemination of information via the world wide web (Roque, Martins, & Lopes, 2013). The so called “nowmad” traveller often plans his entire trip from the stays to the diets, through the tourist experiences, taking into account, mainly, their connectivity (Biosphere, 2019a). If we consider that we live in a world dominated by technology and internet and these tools are changing the way the world interacts and communicates (Keller, 2009), it is not surprising that even in rural tourism there are been an explosion of different means to communicate the product. This is particularly important for businesses located in regions with symptoms of any kind of economic poverty and in businesses distant of its markets, such as the ones located in interior rural areas (Pato & Kastenholz, 2017). The wealth and income generated in rural environments can be increased by improving strategically planned activities that enable rural tourism units to compete efficiently in the market and develop themselves successfully (Peña et al., 2013). In this context, ICT are fundamental, sometimes the only medium via which RTEs can undertake strategies to communicate the rural product (Peña & Jamilena, 2010; Peña et al., 2013). Moreover with ICT, rural tourism businesses can “manage the demand” (Kastenholz, 2004) in a better and proper way.

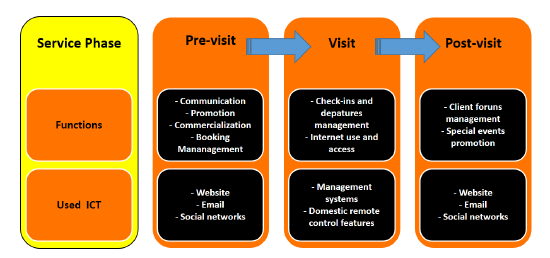

In the present case, the adoption of ICTs refers mainly to the use of the tools and applications associated with intensive use of internet (Romero & Valiente, 2005). They can act in tree and interrelated phases (figure 1): pre-visit, visit and post-visit.

Indeed, ICTs allows RTEs reduce the effects of remoteness (Evans & Parravicini, 2005), to present themselves in the international market, reduce their dependency on intermediaries, direct promote their services (Álvarez, Martín, & Casielles, 2007) and manage forums with clients.

2. Methods

2.1 Procedures

This work uses a case study approach. As a research method, the case study is used in many situations to contribute to knowledge of individual, a group of people and related phenomenon. It allows to focus on a case and retain an holistic and real-world perspective of it (Yin, 2014). The case study implies the use of diverse information sources. In this case, a semi-documental analysis and structured interview is used. The guideline for the interview was based on the literature review about sustainable tourism and ICT. Because this works focus on ICT, the interview was made by skype. It occurred on March 16th. In order to identify the main discourse of the promoter of the rural tourism enterprise, the interview was tap-recorded, transcribed and subject to content analysis. The objective in qualitative content analysis is to systematically

transform a volume of text into a highly organised and concise summary of key results (Erlingsson & Brysiewicz, 2017). The initial step begun with the reading of the interview to get a sense of the whole, i.e., to gain a general understanding of what the entrepreneur was talking about. Then, the text was divided into smaller parts or units, being these ones associated to labels: offer, sustainability, ICTs, communication of the enterprise, rural development, and so on.

Documental analysis, as a systematic procedure for reviewing and analysing documents printed or not (Bowen, 2009), was based on electronic documents about the rural tourism enterprise.

2.2 The case study

The rural tourism enterprise, which this study focus is located in VDLR. Particularly, in one of the most peripheral and interior communities of the region, municipality of Mangualde. The rural tourism enterprise, classified as a country house was born in a pedagogical farm with 2,5 ha in 2012 (Pato, 2019b). Currently the enterprise has three houses: “Casa do Carvalho” (Oak House), “Casa do Celeiro” (Barn House), “Casa das Aromas” (Aromas House) and one suite - “Quarto do Mocho” (Owl´s Room). Each house is prepared to receive up to four people, with a fully kitchenette that allows to prepare meals; the suite welcomes up to two people. The farm has many amazing places to rest and enjoy: the permaculture garden (“Ritinha” Garden), where the pesticides are banned and replaced by herbs and natural products for pest control; the biological pool instead of a conventional pool; the “Aldeia da Bicharada” where animals are in charge of mixing it with nature; the “Aromas Garden” with lovely aromatic plants, and the “Palmeiras Lounge”, with a fantastic environment. Moreover, apart other sustainable certifications, this enterprise is also certificate by “Acessible Portugal” to promote accessible and sustainable tourism to everyone.

3. Results

3.1 Sustainability of the enterprise

The birth and development of this enterprise was based on sustainable principles. This is a concern shared not only by the promotor but also by the tourists who seem to search increasingly a sustainable destination (GreenKey, 2019a; Pulido-Fernández & López-Sánchez, 2016).

First at an environmental approach - the windows have double-glazing in order to provide an appropriate level of thermal insulation; the air-conditioned classified with A++ saves energy. Rainwater is routed to a plastic tank and after used for irrigation and watering of animals. As a replacement of a conventional pool, the promotor decided to create a biological pool that increases biodiversity of fauna and flora as well a water source for birds and other animals that go there to drink.

Therefore, it is not surprising that the touristic product is intended for persons with these concerns of sustainability. This “management of demand” (Kastenholz, 2004) and “customer orientation” (Peña et al., 2013) is fundamental nowadays, as the entrepreneur of the unit said:

“My product is mainly for persons (e.g., couples with children), who valorise the environment and its resources: animals, plants and the entire natural space (…) (…) and have concerns with water and energy use, for instance (…)”.

Apart of this sustainable approach, the tourism enterprise follows also principles of economic sustainability. Therefore the relationships with other economic suppliers of the region (e.g., natural soap producers, agricultural producers, sweet producers and local restaurants), which provide some products for the tourism enterprise. Moreover, the social sustainability is also a concern. Thus in order to revitalize local culture and some traditional festivals in the region, the enterprise has healthy connections with the local community and local entities. For example, the entrepreneur, committed to keeping alive the cultural values and memory of the people of the parish, performed a theatrical festival based on the romance “Retrato de Ricardina”.

The sustainability conduct of the enterprise is also visible and evident in its website. Apart of information related with sustainability in the main webpage of the enterprise, it has a specific tab for issues related with environmental and social sustainability.

Moreover, the accommodation is also in a process of sustainability certification, as it was said:

“They are two, the sustainable certifications that I hope that this house will reach in the very near future. For one hand the certification of Biosphere and for another hand the certification of Green Key. This is good for us because improves the performance of the enterprise (…) (…) we want to reduce the ecological footprint (…) (…) is also good for tourist because they will see and recognise the accommodations that are really sustainable. Even today we saw the demonstration that was made by young people about the climate change (…)”!

Moreover yet, Booking.com is partnering with Green Key to highlight Green Key awarded properties on its site as sustainable (GreenKey, 2019a). The promotor also shares this fact:

“Booking.com itself is already picking up the units that have the green key certification to be select by tourists when they select the accommodation. Green key has advanced in that direction. I think that Biosphere is going to present also a candidature to Booking with the purpose to be integrated in their channel (…)!

Besides the environmental concern, as it was shared by the “the Bruntdland report” the economic and social responsibility is also a concern of the RTE:

“But we have not only environmental concerns - we also have social concerns, that is about the community and we also have economic concerns (...)”.

It is important to emphasize however that these sustainable certifications attest that this enterprise is really a sustainable accommodation, but even without these, the enterprise was already sustainable!

3.2 ICT and communication of the sustainable enterprise

The importance of ICTs, mainly to communicate and promote the rural tourism enterprise is fundamental, allowing to reach distant and sometimes foreign markets (Peña & Jamilena, 2010; Peña et al., 2013). Accordingly, a great part of the time is dedicated to communicate the offer, as the supplier said:

“Around 70% of my time is dedicate to communicate and/or commercialize the offer. I emphasize facebook and instagram, update the site, respond to comments that are made on booking.com and tripadvisor, update of distribution channels, write publications for magazines and we have to do the texts and often translate the texts for english…”.

Indeed the enterprise use many tools to communicate the product.

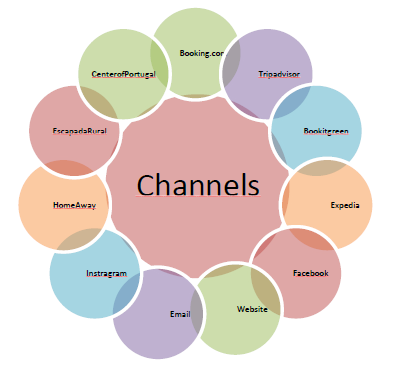

“We use many tools to communicate our product. At once the web page and social networks, such as Instagram and Facebook (… ) (…) the enterprise is also promoted by other platforms - HomeAway, Escapada Rural, Center of Portugal, Booking.Com, Trip, Advisor, Bookitgreen and Expedia…”.

Some of these channels are very dependent of the supplier. They are identified in the four below circles of the figure 2 and refer to the web page, email and social networks (facebook and instagram). These require a permanent dedication by the supplier and have a great impact on reservation in the unit. Indeed, almost 60% of the reserves in the enterprise are made directly, that is, without recourse of intermediaries.

It is also interesting to note that some of these tools are specific of rural tourism enterprises, particularly EscapadaRural, while others, particularly Bookitgreen, are specific of sustainable accommodations.

Despite this, the promoter feels that some information are not reaching tourists, mainly to the foreign ones. She gave the example of a foreign couple with children that had difficulties to find an accommodating like the one that she has and that focuses on sustainability issues. For this reason, she decided to change the name, adding “pedagogical farm” to the existing name of the enterprise, as she said:

”I suggested a change in the name of the house. Thankfully, booking.com also agreed. Then, it stayed the name of the house plus «Pedagogic Farm». For instance for a Chinese the name «Casa das …» doesn´t make sense, but «Pedagogic Farm», an universal concept, makes sense”.

Apart of these ICT tools, the promotor has also a management system to control demand, particularly a channel management. It has multiple functions: reserves management, email sending, communication to foreign and borders service (SEF), payments and so on.

Conclusions

The main contribution of the present study lies in the competitive strategy that is put forward in the form of adoption of sustainable conduct and use of ICT for the communication and delivery of the tourism product. This is particularly important because RTEs need strategies that are compatible with their scarce resources (financial and others) and that contribute to strengthening the elements most highly valued by tourists (Peña et al., 2013). This strategy seems to result since nowadays the RTE presented here has a reasonable occupancy rate, with perspectives for growing in the near future. Moreover, the region and the community will also be grateful for this sustainable conduct.

We also think that other RTEs of the region can be inspired by the example presented here. Therefore applying this combined strategy of sustainable conduct and ICT, other RTEs of the region can achieve better outcomes in terms of environmental, social and economic sustainability.

A second contribution of the study relates to the effect of “management of demand” and “customer orientation” that ICT allow. In fact, rural tourism may contribute to sustainable destination development but the realisation of this potential depends basically on the type and behaviour of the tourists attracted (Kastenholz, Eusébio, & Carneiro, 2018).

In each of the three phases - pre-visit, visit and post-visit, ICT are fundamental to attract a customer that value which is environmentally friendly and contributes to the well-being of the community

As an exploratory study, this work has certain limitations which themselves constitute future lines of future research. Because time constraints, we did only one interview to one tourism supplier. Therefore, it would be interesting to extend the study to other tourism rural suppliers of the region to see the strategy that they follow in terms of communication, specifically the use of ICT, relating this with management of demand and customer orientation. Another path for future research is to focus in tourists themselves to see in a deeper way what tools they used to choose the sustainable RTE.