Introduction

School retention in Portugal is a serious issue, because of the high numbers and its consequence in school dropout. The Ministry of Education report includes the analysis of the indicator "Direct Paths to Sucess" of the last triennium (2017-2019). This indicator shows that the majority of secondary school students failed at least one school year or one of the national exams, more than 250 thousand young people. The majority of students who should have finished secondary school in 2019 could not do so without failing one year or at least one of the national exams. In a universe of 456,368 students, only 201,937 (44%) had the so-called "direct success path". The situation is more problematic in secondary education since only 41.22% managed to do so without fail.

Of the 180,317 students who entered the 10th year in 2016/2017, less than 75,000 (74,337) managed to finish high school without failing. However, the percentage of "successful pathways" rose by more than two percentage points (from 39% to 41.22%) in 2018. (Source: http://infoescolas.mec.pt/ 03/2019). It is therefore essential to find out which factors can prevent school retention and to see if the variable involvement of students with the school can prevent school retention. Some studies indicate that student involvement is a predictor of academic performance (Connel, Spencer & Aber 1994; DiPerna, Volpe & Elliot, 2005; Skinner & Belmonte, 1993; Wu, Hughes & Kwow, 2010). It is also interesting to see the influence of the various components of school involvement on academic performance. Lambdin (1996), Jordan (1999), Wilms (2003), Carbonaro (2005), found a positive relationship between the behavioural dimension of involvement and academic performance. Studies that used, in addition to the behavioural dimension, the emotional/affective dimension (Borman & Overman, 2004; Connell, Spencer, & Aber, 1994; Sirin & Rogers-Sirin, 2004) also found a positive relationship with academic performance.

Based on these postulates and using the the four-dimensional scale about Student's Engagement in School (EAE-E4D) written by Veiga (2013, 2014, 2016) the following objectives were established:

Determine in the sample the retention rate by gender and school career (humanistic and professional scientific courses).

Compare the students who failed the year and the students who did not fail in the results presented, at the beginning of the school year, in the cognitive, affective, agency and behavioral dimensions of the scale of involvement of students in school (EAE-E4D)

Compare the students who failed the year and the students who did not fail in the results presented, at the beginning of the school year, in the cognitive, affective, agency and behavioral dimensions of the scale of involvement of students in school (EAE-E4D)

Deepen the affective dimension of the scale (EAE-E4D) about the students who failed and students who did not fail.

1.1 Retention: concept, legal background and statistical data

School retention means the student will stay in the same school year for an additional period, instead of moving on to a higher level together with his/her age peers (Brophy, 2006). In Portugal, the legal framework related to school year transition is like most European countries, which have lower retention rates. Therefore, the conclusion is that high retention rates are not a consequence of the legal framework (Perdigão, Rute & Ferreira, Antonieta & Félix, Paula,2015). Portuguese legislation (Decree 98-A/1992 of 20 June 1992) defines that in secondary education, in the scientific-humanistic courses, the student's approval in each subject depends on obtaining a final score equal or superior to 10. In the last year of multi-annual subjects, attendance score cannot be less than eight. Student’s transition to the next school year happens whenever the final grade is not less than 10 for more than two subjects. In vocational courses (labor market-oriented), a student does not move forward, if he/she has more than ten modules in arrears. Although the evolution of retention and dropout rates have shown an improvement in the last decade in all school years, Portugal is among the three OECD countries with the highest retention rate (31.2%), only surpassed by Belgium (34%) and Spain (31.3%), with the OECD average rate being 12 (Graph 1)% . In cycle transitions, the retention values increased in the 7th and 10th grades, critical moments in a school career. In Portugal, this percentage is higher than 50% for young people aged 15 with a problematic socio-economical situation, compared with the OECD average of 20%. ( Source: OECD, PISA, 2015). According to Duarte et al. (2008), a cycle transition can be a difficult phase in terms of students' adaptation and lead to a decrease in their academic performance.

Portugal has participated in all PISA cycles to date - 2000, 2003, 2006, 2009, 2012 and 2015. In 2015 the sample was 7325 students with 15-year-old from 246 school clusters throughout the country. Since 2000, Portugal's average results have consistently improved in three areas (Portuguese, Mathematics and Reading), approaching the OECD average scores. Between 2009 and 2012 there was some stagnation in the results, improving again in 2015. PISA 2015 edition showed that Portuguese students improved their grades in all areas (Mathematics, Reading and Science). Considering the 35 countries/economies included in the OECD, Portugal now reaches the following positions: 17th in Science with 501 points, 18th in Reading with 498 points and 22nd in Mathematics with 492 points, being above the OECD average in all areas. Despite the improvement, Portugal is in the top 3 of the percentage of 15-year-old students who have failed at least once. Retention and dropout rates (2012-2016) in secondary education (humanistic, scientific courses) tend to reduce, albeit small, in 11th/12th grades and remain stable in the 10th grade. (Source :OECD, PISA, 2015)

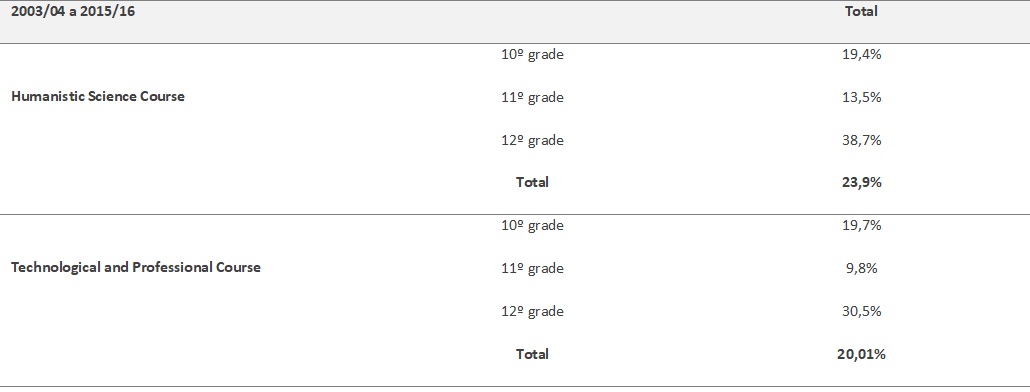

The average data on school retention (2003/04 to 2015/16), provided by the Ministry of Education (Table 1) shows that humanistic and scientific courses have a higher percentage than technological and vocational courses in the 11th grade (difference of 3.7%) and 12th grade (8.2%). In both, the retention rate is higher in the last year of high school 38.7% in humanistic science courses and 30.5% in technological and professional courses. Source: http://infoescolas.mec.pt

Table 1 Average Retention Rate per Curriculum Orientation 2003-2016

Source: http://infoescolas.mec.pt

A comparative analysis between women and men revealed a higher retention rate among boys compared to girls in primary and secondary Portuguese schools (Source: http://www.dgeec.mec.pt) . "The advantage of girls over boys in their environment is greater the more deprived that environment is" (Grácio & Sérgio, 1997, p.70). Statistical data proved that the differences in achievement between boys and girls are more significant in low-class families and lower in middle-class and high-class families.

Male retention rate is higher than the female retention rate in all cycles and worsens after the 2nd cycle: in the 1st cycle the difference between boys and girls is 1.4%, in the 2nd cycle 5.9%, in the 3rd cycle 6.3% and in secondary education 7.6%. (table 2) Source: http://infoescolas.mec.pt

The students’ percentage who moved forward until the 9th grade in 2016/2017 47% were girls, while 37% were boys. In the 9th grade, the success rate (zero retention in the 7th and 8th year and positive in the 9th year exams) was 51% for girls and 41% for boys.

In secondary education, the difference between boys and girls rose from seven percentage points in 2015/2016 to ten points in 2016/2017. In the 3rd cycle, the gap rose slightly in one year, from nine percentage points to ten (Source: http://www.dgeec.mec.pt).

1.2 Students’ engagement with school and its connection with school performance

Many studies show that student engagement is an indicator of school performance (Connell, Spencer, & Aber 1994, DiPerna, Volpe, & Elliot, 2005, Skinner & Belmont, 1993; Veiga et al. 2009). It can be defined by the degree of students’ commitment to the school and their motivation to learn (Simons-Morton & Chen, 2009; Veiga et al., 2012). The multidimensionality of this engagement is recognized, regarding the following dimensions: behavioral, emotional/affective, cognitive, academic (Appleton, Christenson, & Furlong, 2008; Fredricks et al. 2004). Even though it is not consensual, which component is more critical, the behavioral and emotional appeared in many studies as the most vital. The transition between educational levels can affect engagement and learning as it implies changes in the level of requirement and often forces the student to change school, which involves adaptation and new relationships with teachers and peers (Reschly & Christenson, 2006). Klem and Connell (2004) realized that students’ involvement diminished as they progressed from primary school to junior high school and from junior high school to high school, while Anderson and Havsy, (2001) show a decline in attendance when changing school years. Some studies also point out the increase on substance use (Henry, Knight, & Thornberry, 2011; Li & Lerner, 2011; Simons-Morton, 2004) and mental health problems (Elias, Gara, & Ubriaco, 1985; Li & Lerner, 2011). In the international study PISA "Program for International Student Assessment", sponsored by the OECD in 2015, the results regarding the feeling of belonging to school showed that 17.7% of students do not feel integrated and 12.9% feel as "outsiders". Regarding the ease of making friends at school, 22.2% reported that they do not have this ability. Besides, 11.8% stated having already suffered some act of bullying, 6.7% said that other students mock them, and 2.3% were already hit or pushed by other students. Interest towards school is measured by delays and absences, especially interim absence. PISA 2015 data showed Portugal and Sweden are the countries where students are later to school: 21% in Sweden and 16% in Portugal showed occasional delays or even frequently. As for intermediate absences Portugal and Spain are where it happened the most, although the percentage of students who admit to frequent or occasional absences is residual. Another yardstick to measure students' interest in the school is disruptive behavior. OECD 2015 study found out that Portugal is one of the three countries where teachers spend the most time keeping the order in class (15.7%), alongside Iceland and behind Brazil (19.8%). A large percentage of teachers (38%) admit having more than 10% of undisciplined students in a class; this percentage is above the OECD average (32%). OECD 2015 study also found out an impact of the variable sense of belonging on academic results in sciences as well as on total life satisfaction. The higher the sense of belonging, the better sciences results and overall life satisfaction. They also compared students who feel outsiders and students who do not feel outsiders in the sciences scores with those who feel outsiders showing worse results (minus 29 points on average without controlling the socio-economic variable and - 23 points controlling that variable). In an ethnographic study (Finne, 1991) on school dropout, one of the main reasons was that students did not feel emotionally involved. Lee (2014) noticed that emotional engagement measured as a sense of belonging is a significant value of reading performance, i.e., students with higher levels of engagement achieved better reading outcomes than students with less. In the same study, the author found out that the effect of this variable on reading performance is partially mediated by behavioral involvement, i.e. students with high levels of emotional involvement show high levels of behavioral involvement and this leads to higher reading scores. The study by Lee (2014) thus verified a direct and indirect effect of the emotional dimension on school performance. Baumesteir and Leary (1995) state that the need to belong is an essential human motivation. Hence, it is natural that when students have a high sense of belonging to the school, this can translate into a more considerable effort in academic activities. Veiga (2016) studied the criteria validity of the EAE four-dimensional scale, comparing two types of students, students with one or more retentions and students without retentions. Both groups expressed a moderate level of agency and cognitive involvement. However, the group with one or more retentions revealed a considerable lower involvement in all dimensions; the most significant differences are in the behavioral and affective dimensions. Nobre and Janeiro (2010), in a study of 134 students from the 9th grade, discovered a positive and significant correlation between achievement and adaptation to school. They also showed a negative correlation between the number of failures and welfare at school. The authors concluded: "students involved feel more motivated, influencing their academic performance positively. Consequently, there is an adaptation in a cognitive, behavioral and emotional level" (p. 3027). In addition to the impact on school performance, there is also an impact on disruptive behavior. Henry, Knight and Thornberry (2011) studied the relationship between involvement and variables such as dropout, delinquency, offence and substance use and it was shown an inverse relationship between involvement and problematic behaviors both in early adolescence and early adulthood. Li and Lerner (2011) analysed the effects of school involvement (behavioral and emotional) on risk behaviors (delinquency and substance use), noting that high levels of involvement, both emotional and behavioral, projected a lower risk of disruptive behaviors and substance use. Hirschfield and Gasper (2011) considered that cognitive, in addition to emotional and behavioral involvement, also predicts a delinquency decrease, both in school and in general. Borowsky et al. (2002) also discovered that retention, the occurrence of school problems, absenteeism and low connection to school are predictors of violence one year after evaluation. Wentzel (2012) considers that learning takes place in a social context, so positive interactions influence students' emotionally and psychologically.

Juvoven, Espinoza & Knifsend (2012) stress the importance of having at least one friend at school in a transition between cycles. Several authors highlight the role of the teacher in promoting student involvement at school (Wang and Holcombe 2010; Birch & Ladd, 1997; Furrer & Skinner, 2003; Ryan & Patrick, 2001), and can be preventive of disruptive behavior (Ryan & Patrick, 2001; Veiga, 2012).

2. Methods

The study is quantitative, observational and comparative since it aims to compare two groups (students who failed the year vs students who did not) on the scale (EAE-E4D), and also has a longitudinal character, since data on student involvement in school are collected at the beginning of the first period, and data on school retention are collected at the end of the school year.

2.1 Sample

The sample contains 330 students in the 10 th grade of a Secondary School of the Lisbon district. The sampling technique was a non-probability sampleofconvenience because of the easy access to the institution where it was done. There is a balance in the sample related to gender, 44.2% - 146 male individuals, and 55.8% - 184 female individuals. Students were from humanistic, scientific courses (80.6%) and professional courses (19.4%).

2.2 Data collection instruments and procedures

Instrument: the Four-dimensional scale about Student’s Engagement in School (EAE-E4D)

The four-dimensional scale about Student’s Engagement in School (EAE-E4D) written by Veiga (2013, 2014, 2016) is a survey of 20 items with the following dimensions: cognitive, affective, behavioral and agency. The response scale is from 1 to 6 (1 being Total Disagreement and 6 being Total Agreement). The author studied the validity of the scale withconfirmatoryandexploratory factor analysis, proving the existence of a structure of 4 factors related to cognitive, affective, behavioral and agency dimensions. Another study of the psychometric qualities of the scale (Silva, Ribas, & Veiga 2017), a confirmatory factor analysis using the AMOS software, confirmed the four-dimensional structure (X 2 /df= 1.758; CFI =.941; TLI = 0,930; RMSEA =.051; PCFI = 0,797). The author also studied the accuracy of the scale related to internal consistency and obtained Cronbach alphas ranging from 0.701 to 0.870. The Cronbach alpha values found in the study (Silva, Ribas, & Veiga 2017) were like those found by the author, with the total alpha being 0.828, revealing a good internal consistency. The Cognitive Dimension evaluates the information process, related subjects, information management, drawing up work plans. The Affective Dimension evaluates the connection to the school, friendship received and practised, sense of inclusion and belonging to a school. The Behavioral Dimension analyses intentionally disrupting classes, being incorrect with teachers, being distracted in class and absent from class. Finally, the Agency Dimension evaluates the student as an agent of action, initiative of students, intervention in class, dialogue with the teacher (Table 3). In this study, the affective dimension was the only one used, with the same items to the questions posed in the PISA 2015 study which assess the sense of belonging and ease in making friends.

2.3 Ethical procedures

We asked the permission to the scale's author (EAE-E4D) who, in addition to giving the authorization, agreed to collaborate in this study. We asked permission to the school's management to carry out the study and to pass over the scale (EAE-E4D) to all classes of the 10th grade at the end of the first term. The information was also requested at the end of the school year for those students who did not pass. After the favorable opinion of the school's management, we requested to the student's parents for informed consent and guaranteed the anonymity and confidentiality of individual results. The scale was applied with the collaboration of the Psychology and Guidance Service (SPO) and it was done in group, in a classroom context, by the psychologist of the SPO at the end of the first period.

2.4 Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed through IBM SPSS Statistics software version 24.0.

To analyze whether there were significant differences between the group that did not carry over from year to year (81 individuals) and the group that carried over from year to year (249 individuals) Chi-square was used in the in the four dimensions and in the five items of the affective dimension and the answers were polarized.

The Chi-square test was used when no more than 20% of cells with expected frequencies ("expected count less than five") below 5 were found, when this happened Fisher's test was used as an alternative.

3. Results

By the end of the school year, retention was 24.6% (81 students), being higher for males (32.4%) than females (18.5%). Regarding the area, there was more retention in humanistic, scientific courses (28.9%) than in professional courses (6.3%).

Using the cutoff value of 17.5 (middle of the scale) for each dimension, we identified the percentage of students in each group who reveal low involvement and used the Chi-square and Fisher test to find out if there were significant differences. In the group that did not pass the year there is a significantly higher percentage of students that reveal low cognitive involvement (43.2%) and low affective involvement (16%), while in the group that passed the year these percentages are 27.3% and 7.6% respectively (X2 = 7,197, p = 0,007** , X2 = 4,947, p = 0,026*). In the agency dimension the difference is not significant, with a high percentage of students with low involvement in both groups (56.8% in the non-transit group and 54.6% in the transit group: X2 = 0.117, p = 0.733). In the behavioural dimension there are also no significant differences between the two groups, with only two pupils in the total sample showing results below the middle of the scale (Fisher, p = 0.431 ). The results of the affective scale were then checked in detail by analyzing the responses to the items (polarizing the responses). The results showed that in the group of students who were held back, a higher percentage felt alone, at the beginning of the school year (16% in the group that failed and 6.8% in the group that did not fail; X2 = 6.289, p = 0.012*) excluded (18.5% in the group that failed and 8.8% in the group that did not fail; X2 = 5.757, p = 0.016*), with a difficult integration (27.2% in the group that failed e 11.6% in the group that did not fail X2 = 4.937, p = 0.026*), difficulty in making friends (29.6% in the group that failed and 18.1% in the group that did not fail X2 = 4.937, p = 0.026*) and felt that nobody liked them (25.9% in the group that failed e 14.9% in the group that did not fail X2 = 5.167, p = 0.023*) Graph2.

4. Discussion

There was a higher retention rate in males and humanistic, scientific courses, a coherent result with the Ministry of Education report (2003-2016). A higher percentage of low affective and cognitive involvement appeared in the group of students who did not pass the year. In the Veiga study (2016) it was found that the group of students who had already had at least one retention in their school career showed less involvement in the different dimensions of the EAE-E4D scale, compared to the group that has no retention. The most significant differences were found in the affective and behavioural dimensions. So the affective dimension emerged as a differentiating indicator for students with and without retention, in the Veiga study (2016) and in this study. In the present study, the results of the affective dimension were further elaborated, and it was found that students who failed were the ones who showed the worst results in all of the items of the affective dimension at the beginning of the school year (end of the first term). In this group, there was a higher percentage of students with feelings of loneliness, exclusion and integration compared to the group that moved forward. These results supported those obtained by the PISA 2015 study which had found a relationship between the sense of belonging and academic achievements, and those obtained by Nobre and Janeiro, 2010 which saw a positive correlation between results and adaptation to school. Therefore, teachers and psychologists should be particularly attentive to these aspects at the beginning of each school year, and the psychologist may use the School’s Engagement Scale (EAE-E4D) to assess and screen at-risk students, especially students with low affective results. For flagged students, the psychologist should conduct additional interviews for further evaluation and afterwards should construct and implement individual intervention plans. These procedures are particularly important in school transitions since it is in the 7th and 10th grades that school involvement decreases, and retention increases. The teacher should pay attention to students with precarious lives and weaknesses, and to those who are shy and rejected by peers (Veiga 2007). It can be a difficult phase and lead to a decrease in their performance and increase school retention (Duarte et al., 2008), changes in psychological well-being and reduce school satisfaction (Rhodes, 2008). The revised literature (Juvoven, Espinoza & Knifsend, 2012) highlights in school transitions the importance of friendships’ quality and their stability, pointing out that the presence of at least one friend can provide the emotional support necessary for adaptation. In addition to the vital role of detecting students at risk, the teacher has a crucial role in increasing students' school engagement by the way he or she conducts the class and relates to the students. Wang and Holcombe (2010) suggest that teachers can encourage students' participation and their connection with the school by giving positive praise, emphasizing effort rather than performance. Teacher support has been associated with several markers of student behavioral involvement, such as high participation in school-related activities (Birch & Ladd, 1997) and decreased disruptive behavior (Ryan & Patrick, 2001; Veiga, 2012). Students who have more support of teachers, have positive feelings towards school and participate more actively in-class activities (Furrer & Skinner, 2003; Ryan & Patrick, 2001).

Conclusions

It is crucial for students to feel that they can have the support of their teachers and the school psychologist and feel they can count on them, especially when arriving at a new school. At the beginning of the school year, the psychologist should introduce himself/herself to classes which start a new cycle. He/she should explain the inherent difficulties of an adaptation and mention the resources that the students have at their disposal to simplify this transition (school psychologist, support classes, study method sessions, peer tutoring, etc.). Besides, he/she should transmit to the students a feeling of optimism and belonging to a "new family". It is also essential to evaluate the school’s engagement in the first months so that teachers and psychologists have time to draw up action plans to promote the integration of those who feel excluded and avoid their failure at the end of the school year. One of the limitations of this study was that the data was only collected in one school. It would be interesting in future studies to collect data with a greater geographical coverage.