Introduction

The competences associated with personal autonomy have come to be considered a transversal instrument of adaptation to different contexts of life, allowing the human being, throughout his development process, to assume his decisions and some control over life, in general (Boud, 1988).

In academic contexts, autonomous learning and self-regulation are processes that demonstrate the student's ability to show initiative, be able to identify and solve problems, define appropriate strategies to achieve their goals and, at the same time, be able to collaborate effectively with the others.

According to Hammond and Collins (1991, p. 13),

Self-directed learning is a process of learners taking the initiative, in collaboration with others, for increasing self and social awareness; diagnosing their own learning needs (social and personal); identifying resources for learning; choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies; and reflecting upon, and evaluating, their learning.

In Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), even though the Bologna Process appoint autonomy as one of the essential competences to be mobilized in training processes, we continue to see resistance from the different actors in the teaching-learning process that has interfere with the creation of learning environments in which students assume a most active role.

According to these assumptions, this article presents the ERASMUS+ project “Interdisciplinary Collaborative Approaches to Learning and Teaching - INCOLLAB”. We intend to highlight its innovative character in the field of pedagogy in higher education, the dimension of integrated learning of a foreign language and content (Content and Language Integrated Learning - CLIL) and the collaboration between higher education teachers in the planning and implementation of learning modules and teaching materials based on a collaborative and interdisciplinary design and intervention.

The teaching of languages with specific content, called CLIL, is a pedagogical approach in which the contents of a discipline are taught in a foreign language with a dual objective in which a foreign language is used to learn and teach content and language, aiming to promote the learning of both (Bonces, 2012; Marsh, 2002).

One of the central objectives of INCOLLAB is the dissemination of innovative educational resources to other HEI professionals, who can adapt it to their educational context, through the availability of teaching-learning modules on a digital platform (https://incollabeu.wixsite.com/project; https://milage.io).

The methodology followed throughout the project is an action research supported by a community of learning and practice. This modality has allowed teachers from higher education institutions (HEIs) involved in the project, from the areas of foreign language (English, Spanish) and from different content areas (Psychology, Education, Economics, Management…), to share knowledge, competences and pedagogical perspectives, projecting this experience in the design and implementation of interdisciplinary learning modules.

The institutions involved in the project are: MIAS School of Business, CTU, Prague (Czech Republic); Budapest Business School (Hungary); Polytechnic Institute of Castelo Branco (Portugal); University of Extremadura (Spain) and University of Algarve (Portugal).

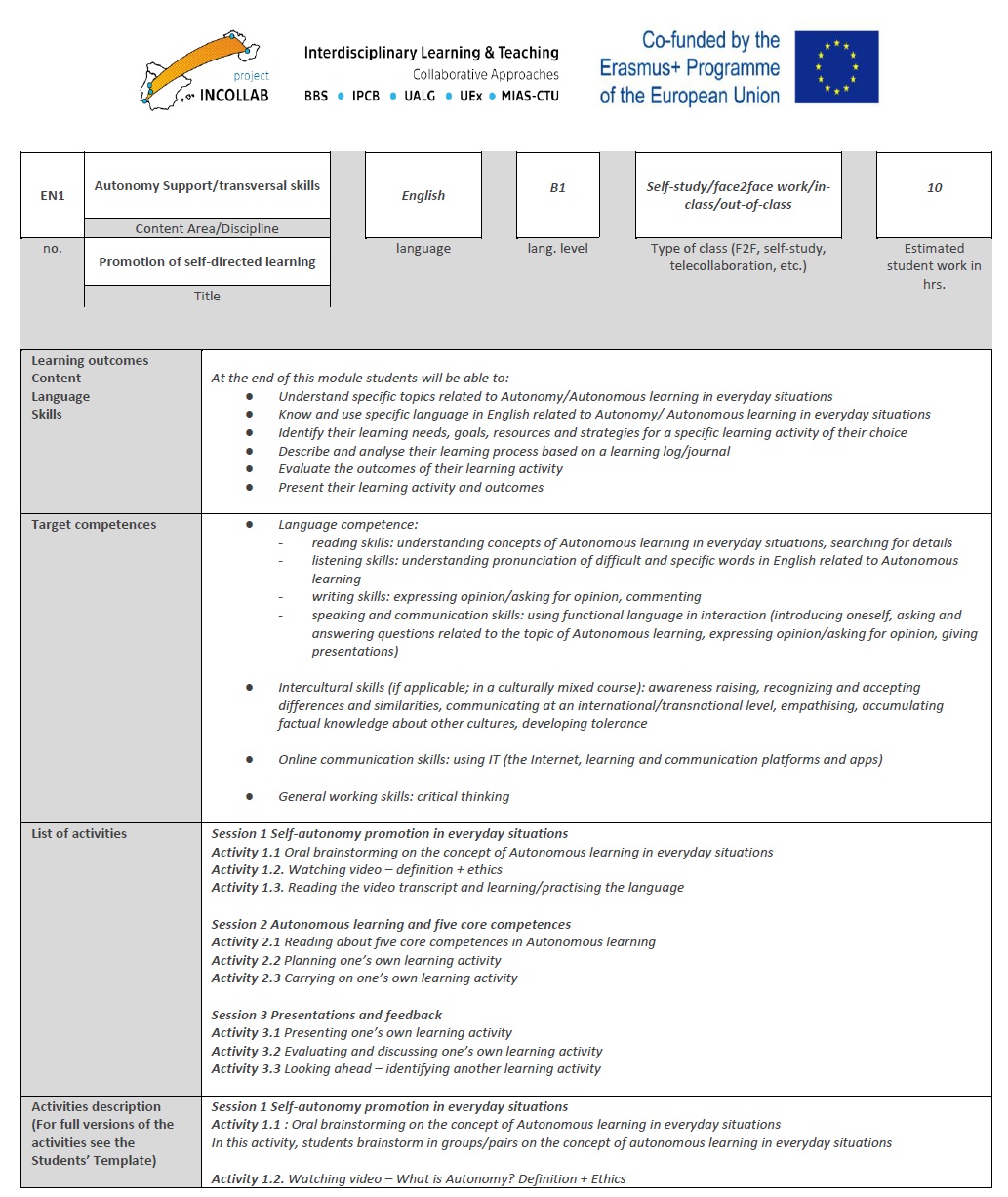

As an example of the work developed, we present, in annex, the module “Autonomy Support - Through collaboration towards self-regulated learning strategies” which is based on the conceptual model of Deci and Ryan (1985, 2004), as well as the learning model interdisciplinary and integrated CLIL.

The reasons for the choice of the module's theme are based on the following assumptions:

Autonomy and self-regulation in the learning processes, as well as the mastery of the English language, are organized as fundamental and transversal competences for academic and professional success;

The organization of teaching-learning processes must respond to human needs for autonomy, competence and relationships, promoting autonomous motivation processes.

HEIs can play a central role in promoting these competences (Clifford 2006), through the implementation and experimentation of active learning methodologies, based on knowledge co-construction processes and supported by pedagogical strategies and materials that promote an active construction of knowledge by students.

1. CLIL INTEGRATED LEARNING MODEL

The CLIL methodology began to develop in the European context, in the 1990s, with the aim of valuing the advantages of learning environments that are linguistically and culturally diverse (Lasagabaster and Sierra, 2010, referred by Coyle, 2015). It aims to promote integrated and interdisciplinary learning processes towards a new era characterized by educational contexts with multiple and diverse literacies and intercultural learning (Marsh, 2002).

It is a pedagogical approach in which the contents of a discipline are taught in a foreign language, having as its underlying a dual objective in which a foreign language is used to learn and teach content and language, aiming at an integrated learning of both. (Bonces, 2012; Marsh, 2002).

It is important to emphasize that while students learn the contents provided for in the formative curriculum, they learn in parallel:

A way of communicating in a foreign language through the use of the concepts underlying the content;

The use of language to communicate the process and the product of the learning;

The language that emerges in communication with colleagues and the teacher in the learning context (Coyle et al., 2010).

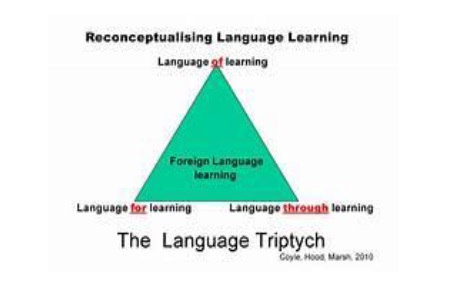

The image reproduced below summarizes the conceptualization presented by Coyle (2010) for learning a language, according to the CLIL approach.

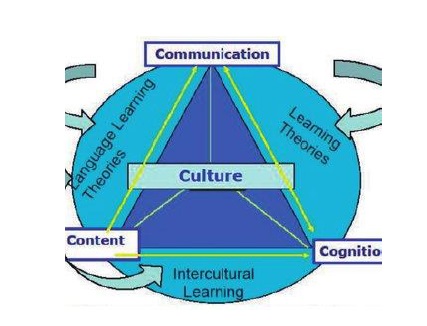

In turn, the 4Cs conceptual framework was developed in the 1990s by Coyle et al. (2010) from the work developed by a group of teachers who implemented the CLIL methodology in different contexts, in order to provide a guide to emphasize the fundamental elements of this pedagogical approach (Coyle, 2002, 2010). According to the 4Cs curriculum (Coyle 2015), a CLIL class must include:

Content - Progression in knowledge, understanding and skills related to specific elements of a defined curriculum;

Communication - Use language to learn while learning to use language;

Cognition - Development of thinking skills that link the formation of concepts, understanding and language;

Culture - Exposure to alternative perspectives and shared understandings, which deepen the awareness of otherness and the self.

According to Costa (2016) the CLIL methodology assumes itself as an innovative pedagogical alternative in the context of higher education pedagogy, presenting added value in the learning process at a motivational and cognitive level.

For Morgado and Coelho (2013) the CLIL approach allows to operationalize the learning of a content and a foreign language in an integrated way, necessarily mobilizing an interdisciplinary approach.

The conceptions of the teaching-learning process are inscribed in the socio-constructivist models when considering that learning should be intellectually challenging, should invite students to participate in the class, promote understanding of their role in the construction of learning, as well as the importance sharing with colleagues and teachers in that process.

2. Autonomy in the learning process

2.1 Types of motivation

The theory of self-determination (Deci and Ryan, 2002), is a conceptual model based on empirical research with implications for the understanding of motivational processes. It assumes a particular relevance in the identification of universal psychological needs underlying motivational processes and self-regulation, as well as the goals and aspirations of human beings.

This theory identifies types of motivation, giving particular emphasis to the concepts of autonomous / intrinsic motivation, control of motivation and demotivation, in their relations with performance, relational behaviors and well-being. At the same time, it aims to identify the learning contexts and environments that enhance or inhibit these types of motivation.

Autonomous motivation concerns intrinsic motivation, but it also integrates extrinsic motivation when it is associated with a valued activity that characterizes the identity of individuals.

In situations where autonomous motivation manifests, individuals experience involvement and investment in their actions.

In opposition, the controlled / extrinsic motivation is dependent on a source of external regulation in which the behavior is managed due to contingencies of reinforcement and punishment. In this case, the self-regulation process is motivated by factors such as the need for external approval, avoidance of humiliation or shame, so the individual feels pressured to think, feel and act in a way conditioned by external elements.

These two types of motivation mobilize and direct human behavior, in contrast to the demotivation that means the absence of behavioral intention or motivation.

2.2 Basic psychological needs

The research on intrinsic motivation carried out by Decy and Ryan (2008) allowed them to formulate the hypothesis of the existence of universal psychological needs that must be satisfied for an effective and balanced psychological existence. Subsequent investigations in different countries and cultures, including those of a more collectivist or more individualistic nature, confirmed that the response to the needs for autonomy, competence and sharing / collaboration is a predictor of psychological well-being. According to the empirical results, these needs are innate and universal, regardless of gender, social class or cultural context (Vansteenkiste, Niemiec and Soenens, 2010).

In this sense, the contexts or environments that enhance the response to these needs have a positive impact on personal and social development, promoting a sense of personal fulfillment (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

In short, the need for autonomy refers to the sense of psychological freedom, being determined by the level of external pressure exerted on the actions of each individual (Deci & Ryan, 1985).

The need for competence relates to the need for individuals to actively interact with the world of objects and people in order to feel able to perform desirable actions and to reject those they consider undesirable (Connell and Wellborn, 1991).

In turn, the need for sharing / collaboration refers to the desire to feel in interaction with others and to build mutual and responsive relationships with them.

2.3. Support for autonomy in Higher Education

Personal autonomy is currently one of the skills valued in different contexts, being one of the objectives listed at the academic level, from the most elementary levels of schooling. In turn, employers highlight autonomy as an attribute to take into account, in addition to motivation for the task, a positive attitude towards life, resilience and the ability to solve problems. A simple analysis of the events and challenges that the human being has faced in the last decades, on a worldwide scale, shows the importance of this competencies, often called transversal competences to different contexts of life. Despite the importance that autonomy has assumed in understanding the adaptation process of human beings, teachers and students of HEIs recognize the difficulties in creating learning environments that promote autonomous learning, as well as in assuming interdisciplinary and cooperation dynamics.

In the words of Clifford (1997, p. 177) “The traditional didactic nature of university teaching assumes a passivity on the part of the learner that has been shown to be antithetical to learning”. Although the analysis refers to the nineties of the last century, our perception allows us to consider its suitability for many current educational contexts.

Clifford (2014) considers that in order for autonomous and self-regulated learning to be stimulated in academia, it is essential that teachers build alternative conceptions about the teaching-learning process and acquire management skills in the learning environments in which they assume a role of facilitators and not specialists with knowledge. In turn, students must develop active learning strategies, in order to progressively assume autonomy in the process.

The module “Autonomy Support - Through collaboration towards self-regulated learning strategies” built as part of our participation in the INCOLLAB Project, aims to organize itself as a pedagogical suggestion for the understanding, by teachers and students, of central concepts about the learning process. It aims at implementing and experimenting with active learning methodologies, supported by virtual learning environments, autonomous research, guided questions and the construction of conceptual maps. In turn, the suggestion for assessing learning takes on a formative modality, contemplating self-assessment.

Support for autonomy is an interpersonal behavior adopted by the teacher during the teaching-learning process that aims to identify and promote motivational and strategic resources in students. In this sense, this concept refers to learning environments in which students do not feel pressured to act in a pre-determined way, being encouraged to make choices and make decisions, assuming their individuality (Ryan and Deci, 2004).

3. Methodological design of the project

In response to the objectives and context of implementation of the INCOLLAB Project, the partners involved organized their action according to a qualitative methodology, supported by a collaborative research-action design and a learning and practice community (CAP).

A collaborative action-investigation has as its central objective the action, involving researchers who are actors in the context (s) under analysis. According to Bryant (1995, p. 8),

Collaborative action research can therefore be defined as a variety of stakeholders cooperating together to explore questions of mutual interest through cycles of action, experience and reflection, in order to develop insights into particular phenomena, create frameworks for understanding, and suggest actions which improve practice.

This type of methodology makes it possible to implement the desired changes more effectively as it is operationalized in integrated action and investigation processes, with a systemic analysis underlying it.

The scheme presented in Figure 3 presents the cycle of an action-research, in a sequence of conceptualization and planning, intervention, registration and systematization of the intervention, analysis and evaluation of the results obtainec, projecting in successive cycles of reconceptualization, planning, action and evaluation.

Figure 3 Cycles of an action research, in https://rachelyoung.myblog.arts.ac.uk/files/2019/02/actionresearchimage.gif

We found many points of contact between the action-research methodology and the procedures inherent to the methodology of the learning and practice communities (LPC).

According to McDermott (2001), LPCs can be defined as groups of people who share and learn from each other through face-to-face or virtual interaction, with a goal or need to solve problems, exchange experiences, techniques or methodologies, aiming at defining, planning and implementing better adjusted professional practices.

LPCs are spaces for participation, in which members share an understanding of what they do or know, bringing divergent “looks” to particular experiences and to other communities (Wenger and Lave, 1991). The members of these communities are professionals who are willing to analyze problems or problem situations, or to develop resources or instruments, appropriate to the objectives and domain of intervention. In this sense, the lessons learned are conceived and operationalized as a social phenomenon and are located in the context of the lived experience.

The dimensions of a learning and practice community are:

Mutual commitment;

Joint construction;

The shared repertoire (routines, concepts, ways of doing…) (Wenger and Snyder, 2000).

According to Wenger (1998) and Hezemans and Ritzen (2005) LPC are spaces for social interaction, construction of meanings and communication between higher education teachers and, eventually, between them and their students. These communities operate conditions for the sharing and joint construction of teaching methodologies and disciplinary discourses, as well as for learning practices. The most appropriate work methodology to promote rigor in the process and an interaction between theoretical models that support practices, intervention and reflection is, in our perspective, participatory action research.

The first moment of the INCOLLAB Project was marked by the operationalization of interdisciplinary learning communities in each one and among the HEIs involved in the project, allowing the sharing of specialized knowledge from different areas, competences, conceptions and pedagogical methods. At the same time, it aimed at learning the CLIL methodology and strategies based on students' autonomy, through the use of digital tools.

The first meeting of the entire INCOLLAB learning community was in person and took place, during five intensive days of work, at the University of Algarve, Portugal, in November 2019. It was conceived as a training activity that allowed the clarification and deepening of the CLIL methodology, on interdisciplinary collaborative practices and on digital tools for learning. The mutual discovery, as well as the dynamics of sharing experiences, allowed the organization of different groups that began to outline learning modules having, as a first target, the students of the involved HEIs. In turn, the themes of the different modules were defined according to the needs and interests of the partners involved.

Each constituted team continued to work, between November 2019 and April 2020, according to the methodology already described, organizing the integral sessions of each module, designing the analog and digital pedagogical materials to support learning in the modality CLIL.

We also highlight the advantage that the different groups constituted are international and have members from different disciplinary areas in HEIs, enhancing the use of modules for different contexts.

4. Results

As an example of the work developed, we present in annex (Appendix 1) the module “Autonomy Support: Through collaboration towards self-regulated learning strategies” which, based on the conceptual model of Deci and Ryan (1985, 2004), aims to constitute as an educational resource available, on an online platform, to other professionals who can adapt it to their educational context. Having been applied experimentally, in the 2nd semester of the academic year 2019-2020, with students of the 1st year of graduation, in the context of the Development Psychology curricular unit, it can be adapted to any training area, mobilizing language skills English level B1.

Although it was not foreseen in the initial planning, the confinement we were obliged to during that period, in the different European countries, required the adaptation of the module to the format of online sessions. We believe that this modality does not constitute a significant constraint and does not compromise the involvement of students in the learning process. However, it is evident as a difficulty that some students in the class do not reveal level B1 skills in the English language.

The reflection carried out after the experimental implementation was based on the feedback from teachers and students, collected through a questionnaire made available in digital format, enabling the introduction of improvements to be contemplated in the post-project dissemination and the replication of best practices.

Conclusion

The experience built over the different stages of the INCOLLAB project has constituted an interesting and significant pedagogical challenge that allows us to project knowledge and practices that promote an innovative teaching-learning process.

We highlight the aspects that, in our perspective, were organized as central contributions:

Conceptual support underlying the CLIL methodology, as it allows operational planning and pedagogical interventions based on interdisciplinarity, streamlining the learning of a foreign language in an integrated manner with curricular contents from different scientific and academic areas, at the level of higher education.

The fact that the conceptions about the teaching-learning process are inscribed in the socio-constructivist models, increasing autonomous learning processes, based on the sharing of knowledge and experiences with colleagues and teachers.

The structured planning of the different stages of the project, organized according to a cycle of an action-research, contemplating the training and professional development of the teachers involved;

The opportunity to participate in learning and practice communities with HEI teachers from different European countries, with knowledge in different areas and different pedagogical experiences. This experience made it possible to operationalize the dimensions identified by Wenger and Snyder (2000), such as the mutual commitment around the project's objectives, the joint construction evidenced in the learning modules and the sharing of knowledge, strategies and pedagogical materials.

The exploration and construction of platforms and digital tools to support learning, in the context of the classroom and in autonomous work, individually or in a small group. The mastery of these tools has assumed a prominent place in the new pedagogical approaches, allowing to stimulate a more significant involvement and motivation on the part of the students, with positive repercussions on their learning. Considering the difficulties and reticence expressed by some teachers, this dimension poses, in our perspective, complex challenges in the operationalization of the modules designed by the participants in the INCOLLAB project. However, it also offers a valuable opportunity to, through the learning and practice communities, test and share the skills needed to respond to this challenge.

The theme developed in the module “Autonomy Support: Through collaboration towards self-regulated learning strategies” has proved to be particularly relevant in the context of training in different domains in HEIs. As we mentioned earlier, despite the valorization that training processes attribute to the promotion of autonomy skills and self-regulated learning, HEI teachers and students recognize the difficulties in creating learning environments that promote autonomous learning, as well as taking on interdisciplinary and cooperation dynamics.

In this sense, the contents and materials of that module are organized as challenges for the pedagogical learning of teachers and students, providing motivational and strategic resources for more meaningful learning.

The activities described in this publication have been developed under INCOLLAB: Interdisciplinary Learning & Teaching: Collaborative Approaches, Project number 2019-1-CZ01-KA203-061163, co-funded by Erasmus+.

The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the publication lies entirely with the author(s).