Introduction

Health contexts are characterized as particularly complex and demanding work environments. Nurses are required to permanently update their technical and scientific knowledge and skills and possess professional/personal characteristics which allow them to have the necessary resilience to face complex and unstable work situations in their daily lives ensuring they provide quality care.

Clinical supervision in nursing (CSN) has been adopted in different countries to help cultivate positive work environments, providing professional development and learning and to prevent stress and burnout in nurses so as to ensure quality and safety of care (Markey, Murphy, O’Donnell, & Turner, 2020).

In Portugal there is no known CSN processes formally implemented through national health policies, so investigating this issue is pertinent, particularly with regard to nurses’ perception of it.

It is important to point out that when we refer to CSN, this is understood as a process of peer supervision, within the scope of supervision among nurses; clinical supervision (CS) is referred to here in a broader sense and not restricted to nursing.

This study is part of a broader investigation with the aim of understanding the representations of nurses in primary health care regarding clinical supervision in nursing.

1. Theoretical framework

Clinical supervision is a process that involves a professional relationship between a supervisor and a supervisee where the supervisor facilitates the development of the latter, helps them to critically reflect on their practice, behaviours and decisions, provides learning opportunities, professional support and guidance (Snowdon, Leggat, & Taylor, 2017; Health Service Executive, 2019; Markey et al., 2020). By facilitating conditions and learning opportunities, support and professional guidance for the supervised, CS promotes high standards of ethical practice and ensures the well-being of professionals and, ultimately, patients (Health Service Executive, 2019).

There are several definitions of clinical supervision, sometimes used indiscriminately, in an ambiguous and incongruous manner (Cutcliffe, Sloan, & Bashaw, 2018). Although there is no consensus on a definition of clinical supervision, there is unanimity as to its function and purpose. It can be summarized as a process of facilitation, professional support and learning, which seeks to create an environment in which participants have the opportunity to evaluate, reflect and develop their clinical practice through the support provided with a view to promoting safe practices (Pollock et al., 2017; Esteves, Cunha, Bohomol, & Reis Santos, 2019; King, Edlington, & Williams, 2020).

Three main functions of CS are recognized: training, the educational/learning perspective; the restorative, inherent to professional support; and the normative, inherent to standards of care and professional responsibility (Proctor, 1986).

Studies have shown that CS it is mainly a primary support mechanism for professional development, with very positive effects on nursing practices overall (Evans & Macroft, 2015; Snowdon et al., 2017). As for the restorative function, the evidence legitimizes CS as the process that provides emotional support that facilitates stress relief, prevention of burnout, enables professionals to deal with stressful situations and environments and develop resilience through the exploration of emotions, managing expectations and developing coping strategies (Francis & Bulman, 2019; Kuhne, Maas, Wiesenthal, & Weck, 2019; Markey et al., 2020).

CS also has effects on learning, inherent to the training function. It encourages evidence-based practice, reflection on practices, critical thinking and decision-making, self-criticism, the development of skills and attitudes, thereby, empowering nurses to take responsibility for their practices (Tomlinson, 2015).

As for the normative function, it provides guidance to professionals to identify opportunities for personal and professional development, facilitates the professional support necessary for discussion and critical reflection on behaviours and optimizing practices as well as assuming professional responsibility in maintaining quality standards of care and the service culture in organizations (Markey et al., 2020).

2. Methods

Qualitative, exploratory study, guided by the principles of action-research in which interaction was highlighted with the context and participants enabling an in-depth analysis of the phenomenon under study.

2.1 Participants

There were 42 participating nurses from a Health Centre Group [Agrupamento de Centros de Saúde - ACES] in the northern region of Portugal.

2.2 Data collection

The data was collected through semi-structured interviews. The script included five thematic blocks: the first included the legitimacy of the interview and respective objectives; the rest included questions related to the participants’ conceptions, representations and opinions on the topic of clinical supervision in nursing.

2.3 Data analysis

The interviews were audio-recorded and then verbatim transcripted. The content was analysed according to the principles of the Grounded Theory method (Strauss & Corbin, 2008) using the Nvivo10® program. Whenever it was deemed necessary, we went back to the field for the purpose of validating the information.

2.4 Ethical procedures

This research was approved by the Board of the Health Centre Group where it was carried out and by the Ethics Committee for Health of the Northern Regional Health Administration. The participants signed an informed consent form and confidentiality was ensured. Interview coding was used (the respondent was assigned the code “E”, followed by the order number of the interview and the code of the respective health centre - CH, RP, VP, respectively).

3. Results

The participants were predominantly female (85.71%; n= 36), aged between 28 and 59 years (M= 44.19; SD= 7.43), with between 6 and 40 years (M= 20.27; SD= 7.21) of professional practice. The most representative professional categories were graduated nurse and specialist nurse in equal percentage (42.86%; n= 18).

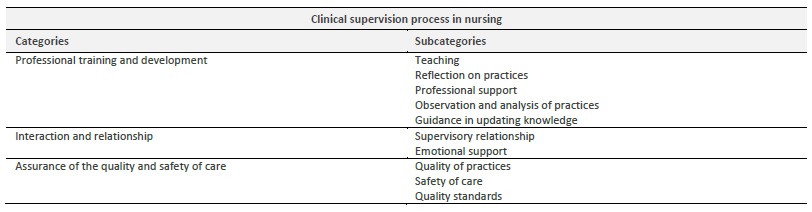

From the analysis, the domain “Clinical supervision process in nursing” emerged, which resulted in the following categories: “Professional training and development”, “Interaction and relationship” and “Ensuring quality and safety of care”, and respective subcategories (Table 1).

The category “Professional training and development” is comprised of the following subcategories: “Teaching”, “Reflection on practices”, “Professional support”, “Observation and analysis of practices” and “Guidance in updating knowledge”. The category “Interaction and relationship” is made up of the “Supervisory relationship” and “Emotional support” subcategories. The category “Assurance of the quality and safety of care” consists of the subcategories “Quality of practices”, “Safety of care” and “Quality standards” (Table 1).

4. Discussion

Regarding the domain “Clinical supervision process in nursing”, we emphasise from the outset the fact that some of the participants understand the CS as a process:

It’s like this, for me clinical supervision, shall we say, is a process. . .between the supervisor and the supervised. E6CH; . . .supervision is a process. . . E14CH

The term “process” (from the Latin processus), refers to the method, a program that regulates a sequence of operations to be performed, with the purpose of achieving certain results, that is, the orderly way of doing things. This perspective of the participants, that CS should not be done ad hoc, but that it requires a method for its operationalization, is congruent with the study by Tavares (2013). The author states that despite little awareness, some nurses have the perception that the CSN presupposes a process.

Effectively, CS has been described as a process from the outset by the Department of Health of the United Kingdom, which presents one of the first definitions of clinical supervision and is also one of the most consensual in the field of health “a formal process of support and learning. . .” (Department of Health, 1993, p. 15).

Moreover, most scientific evidence refers to CS either as a process or as an effective method of professional development, which requires formally defined implementation procedures, as can be seen in practically all documents available in the literature on policies and guidelines on CS (Martin, Kumar, & Lizarondo, 2017).

4.1 Professional training and development

This category reflects the participants’ perception that the CSN process includes functions of a training nature, with the subcategories “Teaching”, “Reflection on practices”, “Professional support”, “Observation and analysis of practices” and “Guidance in updating knowledge”.

In the nurses’ discourse, it is clear that they understood CSN as a training process:

For me, supervision is a training process, of helping people to develop, to train themselves as professionals (E14CH); CS is to ensure training issues. . . (E7CH).

The opinion of the participants is in line with the evidence that has been placing the CSN at the centre of training processes, monitoring of the clinical practices and professional development of nurses (Martin et al., 2017; Snowdon et al., 2017).

Regarding the subcategory “Teaching”, the participants mentioned:

. . .but, on the other hand, CS is also almost like educating, teaching (E12VP); . . .[it] is to teach, train and instruct. . . (E15CH).

In the study by Tavares (2013), nurses also identified a theoretical and practical teaching component in CSN. Supervisory practices are infused with knowledge transmission strategies from the supervisor to the supervised. There are several theorists and government/institutional and research documents which refer to CS as a process that involves education, teaching, and learning, focusing on the objective of teaching and establishing a teaching-learning relationship, improving strengths and identifying the weaknesses of the supervised (Tomlinson, 2015; Martin et al., 2017; Snowdon et al., 2017).

Regarding the subcategory “Reflection about practices”, the participants mentioned:

Supervision for me is a sharing of knowledge, both for those who are in charge and for those who are being supervised. Sharing knowledge, learning (E7CH); . . . There is sharing of knowledge, sharing experiences, asking questions. And I think that’s what CS is! (E2RP); . . . it is to reflect on what can be improved . . . (E3CH).

In some of the first CSN studies carried out in Portugal, Tavares (2013) for example, nurses referred to CSN as a training process that involved reflection on clinical practices. Indeed, there is a great deal of evidence showing that CS is seen as a key to reflective practice (Allan, McLuckie, & Hoffecker, 2017; Martin et al., 2017; Snowdon et al., 2017).

From the analysis, the subcategory “Professional support” also emerged as a fundamental resource to be used in supervisory processes, as it constitutes an attribute/structuring element of professional training and the development of supervisees:

. . . CS is more in the sense of supporting and helping, I would even say it is more in this sense, and not to police (E12CH); I understand CS as follow-up, guidance, clarifying doubts, listening to the other. . . more or less that way, professional support (E17VP); . . . it is support from one colleague to another, someone who is always there when needed in some way an aid (E1RP); It’s having someone who really supports me and who I know, if any situation arises, I can turn to that person (E4CH).

This idea is translated across the available evidence, with many studies proving that CSN allows nurses to discuss and regularly analyse their practices in an environment of safe and supportive assistance (Allan et al., 2017; Martin et al, 2017; Snowdon et al., 2017). Other researches evidence the positive effects of CS as a key support mechanism for professional development, with overall very positive effects on nursing practices (Evans & Macroft, 2015; Snowdon et al., 2017; Markey et al., 2020).

“Observation and analysis of practices” was another of the subcategories that emerged. Participants referred to observation in the context of supervision as:

My perspective of CS is that I am working with a group of colleagues and, not in a pejorative way, check, observe how they do certain procedures, and try to discuss with colleagues if [the procedure] is correct or not, so that we can progress professionally favourably (E16VP); . . . I think CS is a way of observing work, improving practice, professionally . . . through observation . . .. (E3CH).

The opinions of these nurses are in line with the understanding that monitoring and observing practices in a non-pejorative way, allows us to understand how professionals organize and provide care.

Tavares (2013) identified observation as an important CSN strategy. It should be noted that for Alarcão and Tavares (2018), the supervision processes should be based on observation so that no observable episode goes unnoticed, constituting a fundamental strategy to analyse and understand the observable phenomena and the reasons that underlie them.

In short, observation allows first-hand data to be collected from a real situation or other professional events involving face-to-face and other interactions between observer/supervisor and the observed/supervised, during the analysis of their professional activity, with the objective of defining the next steps of supervision thereby optimizing the performance of the supervisee (Abiddin, 2008).

“Orientation in updating knowledge” was another subcategory that emerged from the participants’ discourse:

Orientation is always good when we try to bring ourselves up-to-date with new knowledge that arises. I think [CS] is necessary, in the sense of being able to guide as well as in terms of acquisition of new knowledge, . . . guidance, I think it is only good . . . (E13CH); . . . it may even be necessary to do some research, . . .. And even make us go and study, why not? Even studying other new, more up-to-date practices (E4CH).

Some studies suggest that supervisors are aware of the importance of their role in training supervisees in acquiring their knowledge and developing skills in order to increase clinical experiences. In this sense, the quality of the research sources they indicate is a fundamental component in the support and continuous training of professionals (Myall, Jones, & Lathlean, 2008; Rogan, 2009).

Also in the CS policies of government bodies in different countries, including Community Health Oxfordshire (2010), systematic reference is made to the need to develop evidence-based practices as one of the core elements of CS.

4.2 Interaction and relationship

The category “Interaction and relationship” aggregates the subcategories “Supervisory relationship” and “Emotional support”.

In peer supervision, relationship refers to how supervisor and supervisee are connected, how they work together to accomplish their goals, some of which are common, others of which are idiosyncratic. Participants’ responses show they perceive that CS should envelop an interactive relational process:

For me, that’s how clinical supervision is; let’s say it is an interactive process, between supervisor and supervisee . . . (E6CH); The relationship is halfway created in the supervision. It’s very important! . . . You have to have good relationships to be able to achieve other aspects of supervision, otherwise you won’t get good supervision (E15CH); The issue of the relationship is the main one in supervision (E8VP).

The interactive character of the CSN is irrefutable, and it can be said that most scientific evidence treats the supervisory process as such, as this is only possible in a context of interaction between supervisor and supervisee. The quality of the supervisory relationship contributes significantly to the effectiveness of CS, which is why some authors consider it necessary to deepen the research regarding the relationship between the supervisor and supervisee (Allan et al., 2017 Snowdon et al., 2017; Markey et al., 2020).

The aspects reflected here about the supervisory relationship bring us to the restorative component of CS because as a social support function, it inevitably has to involve a robust relational component, which is also perceived by the participants, so that subcategory “Emotional support” emerges:

I think it can also involve the personal part and, therefore, the sharing of a more emotional problem . . . (E2RP); . . . ensuring more personal support issues, assistance issues (E7RP).

Evidence suggests that CS promotes the legitimacy of emotional support/assistance to professionals through supervisor feedback, providing support, stress relief and prevention of burnout; however, it can only become demonstrable after significant restorative changes (changes in personal well-being) (White & Winstanley, 2010). Other studies highlight the potential of CS to facilitate support that enables professionals to deal with stressful situations and environments and to develop resilience through the exploration of emotions, management of expectations and development of coping strategies (Francis & Bulman, 2019; Kuhne et al., 2019; Markey et al., 2020).

4.3 Assurance of the quality and safety of care

The issue of quality in healthcare has led professionals and organizations to profound reflections on clinical practices. This concern is not recent and extends to different societies and cultures.

Concerns about the quality of practices are also rooted in the participants’ discourse. So, from their analyses, the subcategories “Quality of practices”, “Safety of care” and “Quality standards” emerged, aggregated in the category “Assurance of the quality and safety of care”.

Identifying elements that associate CS with the quality and safety of care practices reveals that a high number of participants, despite not having structured CSN experiences, recognised its role directed to aspects inherent to management, especially in terms of regarding the constant restlessness evident in the speech, regarding ensuring “Quality of practices”, as a central aspect of quality assurance:

I think that CS is an asset for the quality of care (E18VP); Supervision here in the service could help to improve the quality of care and even the quality of professional practice (E11CH); Supervision can contribute to our practices being safe and with quality, yes! Mainly for quality, for safety . . . (E4CH); There are care safety issues here, quality assurance issues, where supervision must exist, otherwise, everyone does what they want, the way they want, come what may! It might turn out fine, but with supervision, the odds that it doesn’t fail are greater in the first place! (E7RP).

The benefits of CS in practices have been assessed “indirectly” from the point of view of the individual perspective of supervisees, in which greater job satisfaction, better work-related attitudes and less stress have been considered beneficial to the practices (Tomlinson, 2015; Allan et al., 2017; Martin et al., 2017; Snowdon et al., 2017; Markey et al., 2020).

In the participants’ responses, the relevance they attribute to the CSN for the “Safety of care” is clear:

The way to control the safety of care would be through supervision (E10CH); I think so, supervision can help in the safety of care and prevention of errors (E6RP); Yes, we are nurses and we run the risk of making mistakes; CS is very important in safe nursing practices, we work with lives. Supervision is important for these practices to be safe (E3VP); Supervision is important, because if you are doing something wrong and you don’t know, if no one shows us, . . . then we will always make the mistake (E5CH).

It was in the wake of needing to ensure the quality and safety of care that CSN emerged in the UK. The Allitt case, which endangered the lives of patients admitted to a hospital unit, sparked an in-depth debate about the lack of safety and quality of nursing care (White, 2017). Winstanley and White (2003) refer to events of the same nature in Australia, which also led to the definition of quality policies that increased the implementation of CSN, considered fundamental and essential to promote safe and quality practices.

Currently, several studies have shown that CS has positive effects on the safety of care (Tomlinson, 2015; Pollock, 2017; Cutcliffe, 2018; Kuhne et al., 2019; Markey et al., 2020; King, Edlington & Williams, 2020).

Finally, the subcategory “Quality standards” emerges from the participants’ understanding of ensuring quality standards through CS in order to ensure the quality and safety of care.

I understand CS as a process of observing and verifying practice, observing compliance with standards, guidelines and procedures . . . (E7RP); It is to check whether through the goals that are recommended we comply or not (E7VP); . . . it also ends up serving to achieve some things in terms of management . . . when I follow up . . . performing these activities [quality standards; establishment of indicators], I’m doing it with a dual purpose, helping colleagues to achieve this indicator or that activity, but also . . . management, there ends up almost being a dual purpose there (E7RP).

These findings corroborate studies that argue that CSN facilitates the identification of solutions to different types of problems in practice, which promotes the improvement of practices and increased understanding of professional issues with the main objective of increasing consumer protection and the safety of care. It also leads nurses to assume their responsibility in maintaining the standards of quality of care and care culture in organizations (Tomlinson, 2015; Markey et al., 2020).

Conclusion

We found that although nurses do not have formal experience of CSN in their practice, their representations about this process are in line with the scientific evidence available. They understood CSN as a process related to training and professional development, interaction and relationship, quality assurance and safety of care. This understanding of CSN establishes a relationship with the three main functions of CS, educational, restorative and normative.

This study may contribute to increasing the adoption of CSN in Portugal, namely in Primary Health Care, contributing to the quality of the nurses’ practice and to nurturing positive work environments that promote the commitment to quality care and nurses’ resilience to respond positively to the stressful elements of the profession.