Introduction

Organisations go through massive transformations over different periods. Those are moments when changes are imperative and frequent, and challenges are created due to increased competition, technological developments, and innovation (Küpers & Weibler, 2008). In a constantly changing environment, organisational change is a permanent condition that will help drive change into organisations to help them adjust to that particular environment.

On March 11th, 2020, the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic, and this announcement triggered several changes in Portugal. Remote working was one of the various restrictions and adjustments brought by this pandemic.

Organisations and individuals were faced with swift and inevitable change. To comply with the social distancing measures implemented, companies were forced to implement remote working, which changed how people were used to performing their jobs. Suddenly, workers from different professional sectors entered a social lockdown process and started working from home. Work became part of family life and soon began to interfere with family life (Losekann & Mourão, 2020).

Although studies focusing on organisational change date back to the early 1970s, the concept is not consensual among researchers, and the "literature studying the attributes that characterise organisational change is quite scarce, scattered and lacks systematisation" (Nery, 2016, p. 27).

Organisational change is a temporal, permanent and continuous phenomenon and includes planned activities that will entail changes in behaviour and know-how to help achieve organisational objectives (Ford & Ford, 1994; Robbins, 2006; Weick & Quinn, 1999).

Change always causes fear and anxiety since each person involved will deal with it personally and will therefore react differently. This sense of fear and concern will trigger resistance to change. Several studies have been conducted in that field, and an increasing number of measurement tools have been made available to assess the resistance to change among workers. However, with organisational change, the consensus among scholars and theorists on those studies and tools has yet to be reached (Nery, 2016).

The way individuals view change is influenced by individual traits since it will depend on how each person perceives it. Emotional competencies will work as facilitators in this transition process, since the "awareness of how our emotions affect what we do is a key competence; those who lack this sort of awareness will be more vulnerable" (Goleman, 1998, p. 62).

As emotional intelligence is becoming an increasingly relevant topic in the organisational context and is considered to be critical for success in occupational settings (Goleman, 1998), this study aims to identify the emotional competencies that may affect the processes underlying organisational change in a remote work context and determine the kind of relationship that exists between emotional competencies and resistance to organisational change.

Organisational culture

The literature provides a wide range of definitions to describe organisational culture. Nonetheless, several elements, such as commonly-shared values and group values, are recurrently popping up. Schein (1996) explains that organisational culture should be seen as a set of implicit assumptions shared and accepted as valid by a group, that will determine how this group perceives, thinks and reacts to various situations.

An organisational culture is then a group of values shared by the members of an organisation that will work as a guideline and through which said members perceive what is right and what is wrong, which behaviours and attitudes to adopt, and that will ultimately define what is expected of them (Yoganathan et al., 2021). It gives them a sense of identity and makes it easier for employees to feel committed to the company. It also helps customers, suppliers, and the community to feel greater proximity to the company, allowing organisations to distinguish themselves from others (Ardichvili et al., 2009; Crozatti, 1998; Luz, 2003; Robbins, 2006).

In the change management process, organisational culture plays an important role, i.e. if the change is to be successful, employees have to be committed to the organisational culture, and, to achieve that goal, they have to know it and understand it. Only thus will its implementation be possible (Galpin, 1996).

Organisational change management

According to Bortolotti (2010), organisational change should be regarded as a transition from a particular situation to another situation that differs from the previous one and encompasses procedures and technologies usually unknown that imply a different vision of how people carry out their work. This transition requires individuals to adapt and adopt new behaviours if the change is to be successful.

In the specific case of the implementation of remote working, individuals and companies were unexpectedly faced with new ways of working. To add insult to injury, these people have to work from home, but they also have to be parents and caregivers simultaneously.

When it is not unexpectedly triggered by issues like those we are currently experiencing - a generalised global pandemic - the need for change should begin by thoroughly examining the internal and external forces that affect the company. Only when the need to change is perfectly accepted will the company be able to move on to the next phase, the diagnosis stage (Chiavenato, 2004). The next step of the implementation has, according to Robbins (2006), two main objectives "first, it seeks to improve the organization's ability to adapt to changes that will take place within its environment, and its second aim is to change its employees’ behaviour" (p. 424).

The existing literature offers several other types of classifications when it refers to organisational change: incremental change; radical change, first-order, second-order and third-order change; episodic change and continuous change (Bartunek & Moch, 1994; Greenwood & Hinings, 1996; Nadler & Tusham, 1989; Weick & Quin, 1999).

1.3 Resistance to Organisational Change

The change process in organisations is always complex since employees must leave their "comfort zone" and adopt new and hitherto unknown procedures (Chan et al., 2021). This process may generate insecurity, some misunderstandings, and discouragement, which, in turn, may cause employee resistance to change (Andrade et al., 2016).

Oreg (2006) defines resistance to change as a personality trait characterised by a tendency to resist and avoid change willingly. When people are forced to experience it, they tend to feel negative emotions. Watson (1971) claims that organisational resistance is related to different domains that are important to shape social and personality processes.

Bortolotti (2010), based on the model designed by Piderit (2000), established a relationship between resistance to change and the specific conditions offered by the context the individual belongs to, like motivation and job security, for instance. She was influenced by the studies conducted by Oreg (2006) since she considers that personality traits (predisposition to change) and consequences (fear, habits and routine) are related to the individual's attitude towards change and that these characteristics reflect cognitive, affective and behavioural aspects of each person.

In their studies, Waddell and Sohal (1998) demonstrate that resistance is a very labyrinthine event and can affect change positively and negatively.

Resistance to change determines the success or failure of change and is most often taken as unfavourable, as it blocks the implementation of change (Andrade et al., 2016).

For some years now, literature has been trying to prove that resistance to change is an enemy; however, the latest literature, although scarce, tends to show that resistance can be good to change since the conflict generated by the individuals’ willingness to resist it will spawn significant amount of energy and motivation that can be used to solve the problems at hand, assess more closely those problems and take a deeper look at the changes that are being suggested. That way, resistance becomes a critical source of innovation in the process of change as more and more possibilities are considered and assessed (Waddell & Sohal, 1998).

1.4 Remote working

The development of technologies and the growth of the information industry have contributed significantly to the increase in the number of decentralised organisations (Degbey & Einola, 2020). Over the last few years, there has been a gradual shift from a traditional work setting, in which workers were expected to perform their activities within the physical premises of the organisation according to pre-established schedules and under the direct supervision of their employers, to a type of work where the workers’ activities are no longer carried out in the central building of the company (Elyousfi et al., 2021).

The agreement signed in 2002 by CES, UNICE/UEAPME and CEEP "defines telework and sets up general framework at European level for teleworkers working conditions” (International Labour Organization, 2020). In Portugal, remote work was legally included in labour contracts in 2003 (Rendinha, 2009; Sousa, 2016).

When the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic and a public health emergency of international concern, the President of the Republic, on March 18th, 2020, said a state of natural emergency for Portugal upon publication of Decree-Law No. 14-A/2020. Following such a decision, measures were taken so that constitutional and legal limits could be observed. This meant, among other rules, the introduction of travel restrictions, with only a few appropriate exceptions provided for, which, in turn, led "to the proliferation of atypical forms of work, and created a context where remote working could gain greater importance" (Resende, 2020, para.24). The swift spread of the virus ended up forcing many companies to adopt remote working.

COVID-19 brought sudden changes to the lives of employees all over the country. The so-called new normal brought significant changes to the working environment: people were literally taking their work into their own homes, no longer had to leave home to work, and soon felt that work had invaded their family and private space. Those are massive changes, and people have had to learn to deal with them and adjust to this new reality.

Adaptation to change is a collective process since organisations are involved, but it is also an individual process since people react differently to similar events. The emotional competencies of each individual are likely to be a differentiating factor in this process of change and in people's resistance to change since they will have a massive impact on the fears, concerns, openness, and predisposition to change.

1.5 Emotional competence

David McClelland published, in 1973, an article in which he focuses on the importance of academic skills since they were a key factor influencing the recruitment of candidates applying to professional positions/functions and because companies were used to hiring people based on those skills. Even though IQ (Intelligence Quotient) tests were applied to assess people’s capacity to fulfil the professional duties required and to hire them, their performance was often poorer than that of workers with lower IQ scores, which took the discussion on these issues to a whole new level (Goleman, 1998).

Over the last few years, researchers have displayed a growing interest in the constructs of emotional intelligence and competence (Cherkowski et al., 2021). The 1970s witnessed the birth of a wide range of studies focusing on how emotions and thoughts influenced each other. This was a new approach since these constructs had always been considered independent constructs, bearing no interaction (Bar-On, 2006; Mayer et al., 2001).

Mayer and Salovey (1997) did not isolate emotional intelligence and did not consider it the opposite of cognitive intelligence. Following their studies, they designed a theoretical four-branch model that encompasses the following biological processes: the capacity to accurately assess and perceive emotions, which refers to the individual's ability to perceive and identify their own emotions or the emotions of other people, as well as stimuli coming from, for example, art or music. The ability to access and generate feelings to facilitate cognitive thought, i.e., the appropriate use of emotions in mental activities, such as decision-making or problem-solving processes. The ability to understand and analyse emotional information, as well as emotional knowledge, that is, to have a deep understanding and knowledge of emotions and why we switch from one emotion to another. And finally, the ability to manage emotions promotes emotional and intellectual development and well-being.

More recently, studies dealing with emotional intelligence became quite popular because of the work conducted by Daniel Goleman. The author showed that a high IQ is no guarantee of success, proving the opposite of what scientific studies had so far shown, without neglecting the extreme importance of cognitive intelligence to the development of human beings. However, he stressed that the capacity to deal with frustrations, control emotions and relate to people acquired as a child would enable them to achieve personal and professional success (Goleman, 1995).

1.6 Emotions and change

Emotions have been studied over the years. The word emotion is derived from the Latin e-move and e-motum, which means to go out, referring directly to the fact that to be able to experience emotion, one has to engage in and use their body to achieve intentional and expressive relationships with the world. Emotions are then dynamic processes and communication events that affect the body, mental, social and cultural relationships, influence and are influenced by the actions of others (Küpers & Weibler, 2008).

The studies conducted by Abreu (2013) focused on emotions, and the author states that "emotion is an individual and elementary phenomenon, easily recognisable in its existence and qualitative diversity: joy, sadness, fear, anger, disgust, surprise, shame, guilt, envy, jealousy" (p. 47).

The study of emotions in an organisational setting is relatively recent and has gained significant impetus over the recent years (Mossholder et al., 2000). In the 1990s, Ashforth and Humphrey presented the relevance of studying emotions in work settings and stressed that work experiences have a very intense emotional component that can include periods of disappointment or well-being and joy (Ashforth & Humphrey, 1995).

For many years, emotions were a topic to be avoided within organisations (Bisquerra, 2014; Huy, 1999) since they were perceived as a barrier to rational and effective organisation and management (Ashforth & Humphrey, 1995).

Back then, organisations tried hard to regulate emotions and even inhibit them. This was a way to avoid the so-called unacceptable emotions that often lead men and women to commit profoundly antisocial acts on behalf of the organisation. However, not all emotions can be avoided, and this negative view of emotions led organisations to hold as tolerable a limited range of emotional expressions that tend to be socially accepted and to deem unacceptable emotions such as fear, anxiety and anger (Ashforth & Humphrey, 1995).

1.6.1 Change Management and Emotion Management

Emotional change management should consider the ability to perceive and express emotions, the capacity to understand them and manage our own and those of others, and the skills of encouragement (Huy, 1999; Mayer and Salovey, 1997).

The management of emotions in the work setting is not straightforward since the negative and positive emotions felt and demonstrated by employees must be taken into account, "the development of emotional skills helps solve problems and conflicts felt in the organization, generate ideas, and fosters a better performance" (Alves et al., 2012, p. 34).

According to Huy (1999), emotional intelligence adjusts to individual changes much easier, and emotional capacity increases the likelihood of organisations implementing change. This particular model addresses the emotional issues linked to organisational change.

According to Schein (1992, cited by Huy, 1999), an organisation’s emotional capability refers to its ability to acknowledge, monitor, discriminate and attend to its members’ emotions and is manifested in the organisation's norms and routines related to feeling. These routines reflect organisational behaviours that express or evoke certain emotional states.

Change is intensely personal, and its management involves working with a fixed set of relationships and handling the process as a whole. The most critical task is to achieve a smooth balance between all the 'pieces' that make up the organisation, understanding how pieces balance off one another, how changing one element will change the rest of the elements and how the whole set affects the structure of the organisation( Wiens & Rowel, 2018).

When an organisation denies the validity of emotions in the workplace or seeks to allow only certain kinds of emotions, employees cut themselves off from the emotions they feel, thus inhibiting ideas, solutions and new perspectives that otherwise would represent some of the organisation’s best assets (Duck, 1993).

2. Methods

This quantitative descriptive and correlational study aimed to understand the emotional competencies at work in organisational change processes in a remote working setting and identify how emotional competencies relate to resistance to organisational change.

2.1 Sample

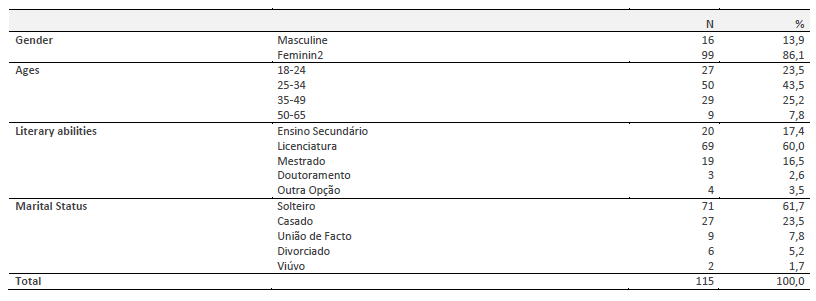

The study sample was composed of 115 employees from different companies located in the district of Viseu who, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, were forced to work from home. The respondents’ distribution according to their gender was heterogeneous since 86.1% were women and only 13.9% were men (table 1).

2.2 Data collection instruments and procedures

The data collection instrument comprises three separate parts: sociodemographic and professional background; the Emotional Skills and Competence Questionnaire (Taksic, 2000), adapted to the Portuguese population by Santos and Faria (2005); and the Resistance to Change Scale (Oreg, 2003), adapted to the Portuguese population in this study. Initially designed in English, the scale was translated into Portuguese and then back-translated into English. No significant differences were found. A pre-test was then conducted with a group of collaborators whose characteristics were similar to those of the target group.

2.3 Resistance to Change Scale

The scale includes four subscales: items 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 belong to the Routine Seeking subscale; items 6, 7, 8 and 9 to the Emotional Reaction to Imposed Change subscale; items 10, 11, 12 and 13 to the Short-term Focus subscale and, finally, items 14, 15, 16 and 17 to the Cognitive Rigidity subscale.

The psychometric properties of the scale were analysed. However, there were significant differences in the results obtained by Oreg (2003), i.e. for the Routine Seeking subscale, item 4 “Whenever my life forms a stable routine, I look for ways to change it” had to be recoded since it was designed to measure the opposite of what the study sought to measure. However, after the item's recoding, the internal consistency value was 0.33. For the Emotional Reaction to Imposed Change subscale, the internal consistency value is 0.76. For the Cognitive Rigidity subscale, item 10 “Changing plans seems like a real hassle to me (a)” was removed, and the internal consistency value rose to 0.62. In the Short-term Focus subscale, item 14 “I often change my mind” was removed since it had a low-reliability index and, thus, the value found was 0.72. In the end, Oreg's Resistance to Change Scale (2003) adapted to this sample of the Portuguese population ended up with 15 items.

2.4 Emotional Skills and Competence Questionnaire

The scale includes three subscales: Perceive and Regulate emotion, Express and Understand Emotion and Manage and Regulate Emotion. Items 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19, 22, 25, 28, 31, 34, 37, 40, 43, and 45 belong to the Manage and Regulate Emotion subscale (MRE); items 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20, 23, 26, 29, 32, 35, 38 and 41 are part of the Express and Understand Emotion (EUE) subscale and, finally, items 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, 30, 33, 36, 39, 42 and 44 belong to the Perceive and Understand Emotion subscale (PUE). In other words, this is a 45 item-scale in which 16 items belong to the Manage and Regulate Emotion subscale, 14 to the Express and Label Emotion subscale and 15 to the Perceive and Understand Emotion subscale.

As for the internal consistency of the subscales, we found an internal consistency of 0.85 for the Manage and Regulate Emotion subscale, 0.80 for the Express and Label Emotion subscale, and 0.81 for the Perceive and Understand Emotion subscale.

2.5 Statiscal analysis

Considering the objectives set out, the following hypotheses were designed based on the studies consulted:

H1: There is a relationship between gender and resistance to change.

H2: There is a relationship between gender and emotional competencies.

H3: There is a relationship between age and resistance to change.

H5: There is a relationship between emotional competencies and resistance to change.

H6: Emotional competencies influence job performance.

H7: Resistance to change influences job performance

3. Results

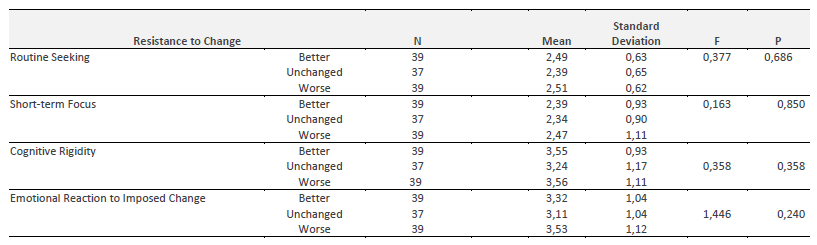

For the first of the hypotheses initially designed (H1), results indicate that there are statistically significant differences between genders but only in the Emotional Reaction to Imposed Change subscale and evidence shows that female participants (M=3.42) have a more significant emotional reaction to change (p=0.014). The hypothesis is then partially accepted (Table 2).

Table 2 Means, standard deviation, Levene test and t-test of Resistance to Change according to Gender

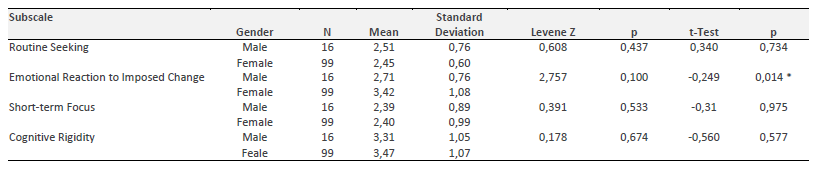

H2 was rejected as there is no evidence of statistically significant differences (Table 3).

Table 3 Means, standard deviation, Levene test and t-test of the Emotional Skills and Competence Questionnaire according to gender

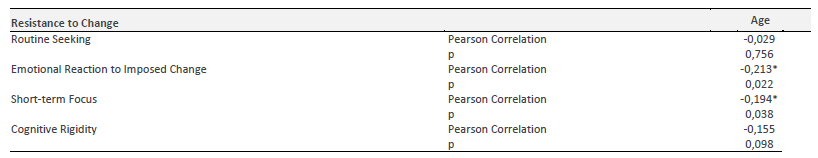

As for H3, which stresses the relationship between age and resistance to change, a negative correlation was found between the Emotional Reaction to Imposed Change subscale and age and the Short-term Focus subscale and age. That way, the older a person is, the lower their Emotional Reaction to Imposed Change and the lower their Short-term Focus. No statistically significant correlations were found in the Routine Seeking and Cognitive Rigidity subscales. Given the above, the research hypothesis is partially accepted (Table 4).

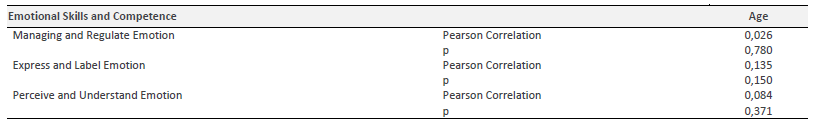

As for H4, results show no statistically significant correlations between age and emotional competence, so this research hypoth5esis was rejected (Table 5).

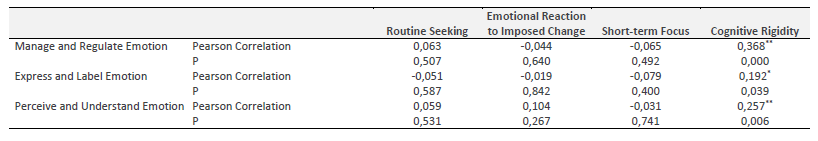

As for H5, a significant positive correlation was found between the Manage and Regulate Emotion dimension and cognitive rigidity (p=.000). A significant positive correlation was identified between the Express and Label Emotion (p=.039) and the Perceive and Understood Emotion (p=.006) dimensions and cognitive rigidity, i.e. the greater the emotional capacity to express and perceive emotion is, the higher the cognitive rigidity will be. That way, this research hypothesis is partially accepted (Table 6).

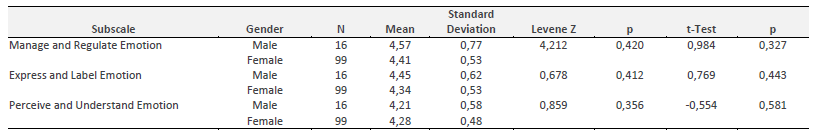

As for H6, no statistically significant differences in emotional competencies were found between job performance categories, so the research hypothesis was rejected (Table 7).

Table 7 Means, Standard Deviation, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) of the influence of emotional skills and competence on Job Performance

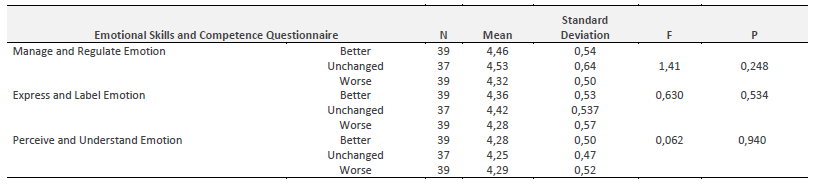

As for the last hypothesis (H7), resistance to change influences job performance, no significant differences were found, so the research hypothesis was rejected (Table 8).

Discussion

The particular context we face across the world and, consequently, in Portugal has required organisations and people who are part of them to rethink how we work. Currently, 70% of workers work from home (Deloitte, 2020). This situation triggers positive and negative emotions (Mayer & Salovey, 1997). Women have to stay at home to work but also take care of their children, who attend online classes. This situation has made the social role of women even more demanding since, in the exact physical location, they have to be both workers and mothers, and, understandably, they are having a hard time “clarifying the boundary between domestic and professional duties” (Rendinha 2009, p. 127).

All these situations have likely generated discomfort and increased stress, as suggested by Oreg (2003), a finding that corroborates and supports our first research hypothesis (H1). On the other hand, the relationship between gender and emotional competencies was not statistically verified (H2), which corroborates Goleman's (1998) studies that state the existence of gender similarities and that both genders are capable of increasing their emotional competence the same way and are, therefore, capable of displaying similar emotional competence.

When we analysed the relationship between age and resistance to change (H3), we found a negative correlation between the Emotional Reaction to Imposed Change and Short-term Focus subscales and age; that way, it seems that the older the person is, the lower their Emotional Reaction to Imposed Change and the lower their Short-term Focus will be. This conclusion is in line with what some authors suggest when they state that the willingness to resist change may increase or decrease during a person’s adult life and may depend on the person’s professional experience (Andrade et al., 2011; Oreg, 2006).

From the literature, we found out that emotional competencies are developed from an early age and evolve throughout a person’s life. That way, it seems that emotional intelligence is not a matter of age (Goleman, 1998; Mayer & Salovey, 2001).

At first glance, we could consider that the results obtained in H5 are not in line with the review of the literature conducted since one would expect that cognitive rigidity would decrease as emotional competence increases. However, other studies have shown that cognitive resources are more effective when emotions are better controlled (Carlson, 2009). This inability to change existing behaviours may occur because the individual believes that that particular change will not meet the goals and objectives they had set for themselves. That way, we may consider that the greater the emotional competence, the better a person knows what they want and how to achieve their objectives. Hence, when that person has to deal with a particular change and believes it will hinder or undermine their goals, they tend to resist.

The results collected from several studies showed a significant relationship between emotional competence and job performance (H6). This shows-contrary to the results of this study- that emotional competence is an important predictor of performance (Bar-On, 2006; Chiavenato, 2004).

The literature review also reveals that resistance does not have to be seen as a negative influence on the organisation. Au contraire, it may be essential to help keep the balance between internal and external pressures, provide an opportunity to assess the reasons why people are resisting, identify and analyse the problems, foment the search for alternatives, and work as a source of innovation and assessment (Mendes & Machado, 2003). Hence, resistance may have no or negligible influence on a person’s professional performance (H7). It should be noted that the context spawned by the pandemic justified the need for change, in this case, the need to work from home

Conclusion

The objectives of this study were, on the one hand, to understand the role played by emotional competence in the process of organisational change involving a remote working setting and, on the other hand, to perceive how emotional competence relates to resistance to organisational change. The results showed that our respondents’ emotional competence scores are pretty high, demonstrating that they can successfully cope with "abnormal" situations like the one we are currently experiencing. The results also showed low scores regarding resistance to change, which reveals a predisposition to change. It can therefore be considered that high emotional competence may trigger weaker resistance to change.

However, in our sample, emotional competence did not seem to have a statistically significant influence on the change processes involving remote working settings, nor did it stand as a differentiator regarding resistance to change. However, it is worth noting that the assessment of the Emotional Reaction to Imposed Change subscale showed that the participants tend to feel uncomfortable when dealing with change.

Some crucial information was collected, though: for instance, the individuals who showed a more remarkable ability to manage and regulate emotion claimed that their job performance remained unchanged, whereas poorer job performance was observed among those who showed a lower capacity to manage and control emotions. Those who managed to better express and label emotion claimed that their professional performance remained unchanged, whereas those who showed a poorer ability to express and label emotion considered that their professional performance got worse. This being said, and in response to our general objectives, we can assume that the ability to manage and regulate change and the capacity to express and label emotion is highlighted in organisational change involving remote working.

It should also be noted that individuals with higher routine-seeking habits considered their job performance worse. On the other hand, those who showed less interest in routine seeking found their job performance unchanged.

Overall, and even though the results obtained were not following the expectations raised by the literature available, we believe that this research proved to be too ambitious when it decided to provide a study that involves concepts on which there is no consensus and that may end up raising additional concern in specific social and organisational settings. Further studies on this topic are thus relevant, as is the adaptation of Oreg's Resistance to Change Scale (2003) to the Portuguese population.