Introduction

Patients seek care when there is a modification to their health condition. Emergency Departments (E.D.) are the facility suited for critical care and are organized according to levels of care. But not every E.D. has all medical and surgical specialities, which leads to the need to transfer critically ill patients for a higher level of care (I.C.S., 2019; National Health Service, 2021).

Critical patient transport is defined as the transfer of patients between different hospital settings with varying levels of care, for example, between district Hospitals and University Hospitals (O.M. & SPCI, 2008).

Determining the level of risk of transport must take into account several factors such as the patient's condition of the patient, risks related to the movement/transfer of the patient, the likelihood of deterioration of situation during transport, the potential need for interventions during the transport, and the duration and mode of transfer (I.C.S., 2019).

A transport decision is the E.D. physician's responsibility, and a set of phases starts to prepare for transport. First, the team responsible for its execution must observe the patient to detect and prevent changes during the transfer. In addition, the clinical history and complementary diagnostic tests performed by the patient have also to be reviewed. Thus, when any hemodynamic change occurs during transport, nurses have prior knowledge to make immediate decisions (O.M. & SPCI, 2008).

There is a higher rate of complications associated with the transport of critically ill patients. Critical care associations suggest that healthcare facilities must develop and implement documents to ensure the patient's quality and safety and the accompanying team (Sociedade Portuguesa de Cuidados Intensivos, Australasian College for Emergency Medicine, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, College of Intensive Care Medicine of Australia and New Zealand and the Intensive Care Society (O.M. & SPMI, 2008; Australasian College for Emergency Medicine & Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists & College of Intensive Care Medicine of Australia and New Zealand, 2015; I.C.S., 2019).

To assure patient and team safety during transfer, the Intensive Care Society, in 2002, suggested using checklists to reduce the risks of transport and check the diverse factors that may interfere with the outcome. Comeau et al. (2015) and Kulshrestha & Singh (2016) report that adverse events related to patients or equipment can occur during inter-hospital transport. These events can include hemodynamic changes, intracranial pressure, agitation, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary and airway complications (such as oxygen desaturation, pneumothorax, ventilator-associated pneumonia, atelectasis, and infections), and blood-related complications glucose levels. And the adverse equipment-related events that occur are equipment failures, disconnected or tangled tubes and wires, and oxygen supply depletion.

According to Hales, Terblanche, Fowler & Sibbald (2007) and Comeau et al. (2015), checklists are instruments that should contain a synthesis of peer-reviewed guidelines based on scientific evidence, reflecting existing policies and procedures of the healthcare facilities. It should be present logically and functionally to allow for a clinical practice sequence and routines. The importance of its application converges to a gathering of large amounts of information, reducing the frequency of errors (e.g., medication overdose or contraindicated medication), creating reliable assessments to improve care, mitigate lack of memory and staff confidence.

Keeping and standardizing records is extremely important to obtain objective data to recognize and evaluate any change to act quickly. Most of the critical care societies note that records should be clear and maintained at all stages of transport, briefly summarize the patient's clinical status before, during, and after transport, including environmental changes and therapy administered, to allow later audits (Australasian College for Emergency Medicine, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, College of Intensive Care Medicine of Australia and New Zealand and the Intensive Care Society (O.M. & SPMI, 2008; Australasian College for Emergency Medicine & Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists & College of Intensive Care Medicine of Australia and New Zealand, 2015; I.C.S., 2019). O.M. & SPCI (2008) and the Intensive Care Society (2019) also state that records should be performed throughout the transport, at intervals, to customize the patient's clinical status. The last vital parameters must be recorded before arrival at the destination hospital.

A preliminary search of MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and J.B.I. Evidence Synthesis was conducted, and no current or underway systematic reviews or coping reviews on the topic were identified.

This scoping review seeks to answer the following question:

- Which clinical data should be in the inter-hospital transport checklist?

1. Methods

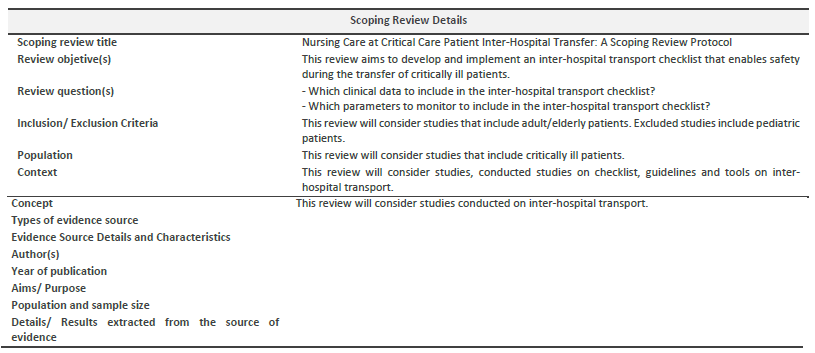

The protocol for this scoping review will be guided following the J.B.I.'s latest guidance regarding methodology. This review protocol is registered in the Open Science Framework.

1.1. Inclusion Criteria

Based on the J.B.I. recommendations on the mnemonic "P.C.C." for scope reviews, inclusion criteria will include: participants - this review will consider studies that have critically ill patients; concept - this review will consider studies on inter-hospital transport; context - this review will consider studies conducted checklist, guidelines and tools on inter-hospital transport, regardless of the country of study; and types of sources - this scoping review will consider any quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods study designs, and inclusion guidelines. In addition, all types of systematic reviews will be considered for inclusion in the proposed scoping review.

1.2. Search Strategy

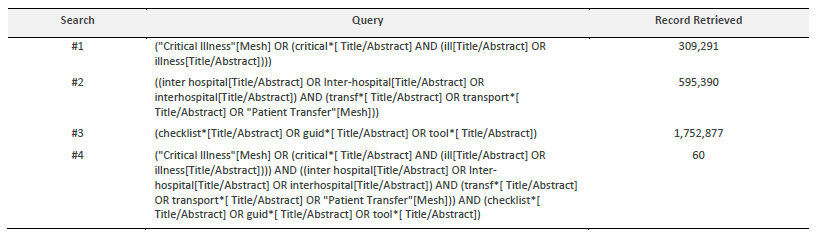

The search strategy will locate both published and unpublished primary studies and reviews. A limited preliminary search was undertaken on MEDLINE (via PubMed) and CINAHL Complete (EBSCOhost) to find articles on the topic. Thus, the text words in the titles and abstracts of pertinent articles and the index terms used to describe the articles were used to create a full search strategy for MEDLINE (via PubMed), as seen in Table 1. The search was conducted on 3 May 2022. The search strategy will be adapted to the specificities of each information source. Lastly, the reference lists of the articles included in the review will be screened for supplementary papers.

The languages of study will be limited to those mastered by the author - English, Spanish and Portuguese - to ensure a good quality selection and data extraction process.

The databases to be searched will include MEDLINE (via PubMed), CINAHL complete (EBSCOhost), LILACS, and Scopus.

1.3. Study Selection

All records identified during the database search will be retrieved and stored in Mendeley® V1.19.4 (Mendeley Ltd., Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), and duplicates removed.

A pilot test will be conducted to verify that the inclusion criteria are met. Secondly, the selected articles will be screened initially by title, abstract, and finally by reading the entire article.

The search results will be detailed in the final scoping review and presented in a Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) flow chart.

1.4. Data Extraction

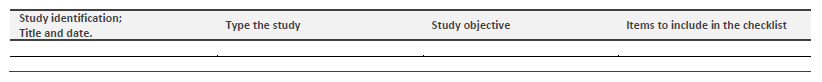

Extracted data from included articles will be charted according to the J.B.I. and aligned with the goals and research questions.

The draft data extraction tool will be modified and revised as needed while extracting data from each included evidence source. Modifications will be detailed in the scoping review. If necessary, article authors will be contacted to request missing or additional data.

1.5. Data Analysis and Presentation

The data collected will be shown in tabular form (Table 3), depending on which is more appropriate to this review's objective. A descriptive summary will be provided regarding the charted result aligned with this scoping review's purpose, and qualitative coding might emerge from the data analysis.

2. Discussion

This scoping review will only consider English, Portuguese, and Spanish studies, which may be a potential study limitation. To overcome this limitation, abstracts of articles published in other languages, which could also be essential to include in this review, will be translated through Google Translator and DeepL to prevent restricting ourselves to programs specific to certain cultures.