Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is defined by the International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) as the involuntary loss of urine, predominantly in women, and its prevalence increases with age, being the most common pelvic floor (PF) dysfunction (Haylen et al., 2010). The global prevalence of UI ranges from 5% to 69% throughout a woman’s lifetime (Abrams et al., 2009), leading to social and emotional discomfort for women with UI (Viana et al., 2014), thus impacting the quality of life (QoL) (Viana et al., 2015; Da Roza et al., 2013). Only 25% to 61% of women with UI seek treatment. Shame, lack of knowledge about treatment options, or fear of surgery may explain this reluctance to seek help (Portuguese Society of Gynaecology, 2018).

Risk factors for UI can be intrinsic (race, genetic predisposition, anatomical or neurological alterations), gynaecological or obstetric (pregnancy, type of delivery, multiparity, post-pelvic surgery, and radiotherapy, pelvic organ prolapse), or other factors (age, comorbidities, obesity, constipation, smoking, occupational activities, urinary infections, menopause, and medication) (Pires et al., 2021; Frawley et al., 2021; Pires et al., 2020a).

According to its aetiology and pathophysiology, UI can be classified into three types with different symptoms: Stress Urinary Incontinence (SUI) (involuntary loss of urine with physical exertion, such as coughing, sneezing, or sports activities), the most common type (33% to 50%); Urgency Urinary Incontinence (UUI) (involuntary loss of urine associated with an urgent need to urinate that is difficult to control); and Mixed Urinary Incontinence (MUI) (involuntary loss of urine associated with both urgency and increased intra-abdominal pressure) (Hagovska et al., 2017; Portuguese Society of Gynaecology, 2018; Whooley et al., 2020).

UI poses a risk to QoL and often leads patients to anxiety, depression, and social isolation (Pierce et al., 2017), as well as physical inactivity, affecting health-related QoL (Da Roza et al., 2012).

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) has been reported as effective in curing or improving UI symptoms in young, middle-aged, and older women with SUI or MUI, as well as in pregnant or postpartum women (Pires et al., 2020b; Dumoulin et al., 2017; Pires et al., 2020c). Clinical practice guidelines recommend individual and supervised PFMT as the first-line treatment for women with UI (Dumoulin et al., 2017; Pires et al., 2020d).

The aim of this study is to assess the effects of PF physiotherapy on pelvic function and QoL in women with UI, summarising and synthesizing the scientific evidence.

1. Methods

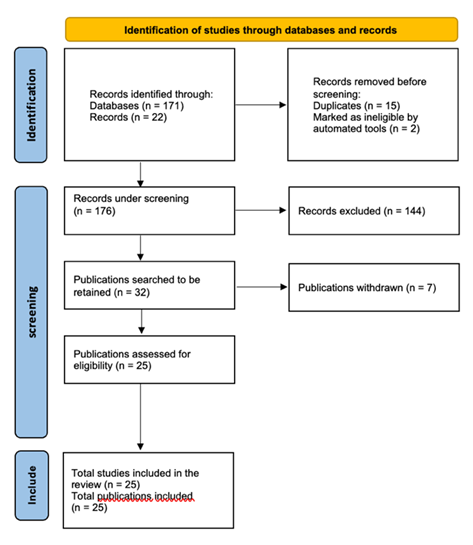

The systematic review was registered according to the PROSPERO protocol (CRD42023488377) and was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., 2021). The research was carried out in the following databases: PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, between January and April 2022. The keywords used were Physiotherapy, UI, and QoL, combined with Boolean operators (AND; OR). The search strategy (TS) used was: TS=(Physiotherapy* OR Pelvic floor muscle training) AND TS=(Urinary incontinence) AND TS=(Quality of Life) AND TS=(Randomized controlled trial OR RCT) AND TS=(Women OR Female), with filters for humans only, articles written in English and Spanish, from the last 5 years. The search was conducted by two independent researchers (EM, RV), who compared both results to check for overlap. Any discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was reached.

After the initial identification, duplicate articles were removed, and all titles and abstracts from the selected databases were screened. Then, potentially relevant studies were selected and retrieved, and the full texts were read to apply eligibility criteria according to the following inclusion criteria: women with UI; over 18 years old; community residents; receiving pelvic floor physiotherapy or under the supervision of a physiotherapist; randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The exclusion criteria were as follows: previous pelvic surgeries; pelvic organ prolapse (POP); pregnant women; on medication for UI; case studies; reviews and meta-analyses. Methodological quality was assessed using the PEDro scale, reported as a valid and reliable tool for measuring the methodological quality of RCTs. These parameters were independently evaluated by two authors (EM and RV), and all discrepancies were resolved.

2. Results

The flowchart of the research conducted is presented below (Figure 1). The characteristics of this study are shown in Table 1. After going through all these stages, 19 RCTs were selected for analysis. The sample size ranged from 31 to 600 women with UI, with participants aged between 20-35, 48-58, and 60-70 years. The most reported type of UI was SUI, with 11 studies (1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 10, 11, 13, 15, 16, 19), 3 studies focused on MUI (5, 6, 9), 2 assessed UI and sexual dysfunction (11, 12), 1 assessed UUI (6), and 5 assessed UI without specifying the subtype, with 1 (18) also evaluating fecal incontinence (FI) in addition to UI. The follow-up duration of the studies ranged from 4 weeks (4) to 36 months (12). There were various approaches, but no uniform standard for PFMT was identified.

The mean methodological quality score of the included studies was 8.42 ±1.73 (range 5-10) out of 10 points according to the PEDro scale. The most common methodological limitation among the studies was the lack of “blinded therapists,” which was nevertheless conducted by 10 studies (1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 12, 15, 18, 19). The lack of “blinded assessors” was also a methodological limitation in 8 studies (2, 4, 8, 10, 11, 14, 16, 17) (Table 2).

To assess the parameters of muscle function, the following measurement instruments were used: perineometer (3, 11, 15, 16), dynamometer (6), and manometry (5, 13, 18), digital palpation using the Oxford Scale (3, 6, 13), digital palpation PERFECT (8, 15), Ortiz Scale (15), and transperineal ultrasound (6). To assess involuntary urine loss, the Pad test (5, 6, 7, 8) and a voiding diary (1, 6, 8, 13, 15) were used.

The measurement instruments used to assess sexual function were: FSFI (11) and ICIQ-FLUT SEX (6, 11). For the evaluation of UI symptoms and QoL: ICIQ - LUTSqol (6, 10, 17); ICIQ-UI SF (3, 5, 6, 10, 14, 15); PGI -I - Patients Impression of Improvement for Incontinence - (5); Australian Pelvic Floor Questionnaire (APFQ) (18); Incontinence Severity Index - ISI - (1); King’s Health Questionnaire (1, 15, 16); PISQ - 31 - Prolapse and Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire (12); SF-36 (12); EQ - ID (12); EQ - 5 D (12); E-PAQ (12); QoL short form - (7, 8, 14, 16); ICIQ-N (6); ICIQ - VS (6); Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (14); Geriatric Self Efficacy Scale (6); and Broom Self-Efficacy (6).

Different types of technology associated with PFMT were used: virtual reality (game therapy) (5); NeoControl chair (extracorporeal magnetic innervation) (19); 1 study that used an Easy K7 device that transmits low-frequency stimulation (11); and 2 studies that employed a mobile application (Tät) for the home self-management of PFMT (2, 10).

Table 1 Characteristics of the included studies

| References | Demographic characterization | Aims of the studies | Duration/ Follow-up | Intervention protocol | Treatment duration | Quantified parameters | Results |

| 1. Abreu et al 2017 | n = 33 Women ≥18 Years | Comparing the results of training with the lumbopelvic technique or PFMT in women with SUI | 90 days | Lumbopelvic technique + PFMT | Sessions twice a week (T:5 weeks) | UI severity, QoL and feeling of improvement | The PFMT was superior to the lumbopelvic technique in terms of the number of episodes of loss, QoL and feeling of improvement after 90 days evaluation (p < 0.001), showing a more prolonged effect. |

| 2. Asklund et al 2017 | n = 123 Women ≥18 Years (±45) | Evaluate the effect of PFMT using a mobile application (app) to treat SUI | 6 weeks | PFMT + app | Twice a month | Urinary symptoms and QoL | App-based treatment was effective for women with SUI with clinically relevant QoL improvements (p < 0.001). Recommended as first-line treatment. |

| 3. Belushi et al 2020 | n = 145 Women ≥18 Years | To determine the effectiveness of PFMT (home) in reducing symptom severity and improving QoL among SUI women | 12 weeks | PFMT at home | 5 sessions per day (T:12 weeks) | PMF strength evaluation by palpation and perineometer, ICIQ-SF | PFMT at home is an effective treatment in reducing the severity of symptoms and improving QoL in women with SUI (p < 0.001). |

| 4. Bertotto et al 2017 | n = 31 Women ≥18 Years (±58) | Comparing the effectiveness of PFMT with and without BFB in increasing MS, improving electromyographic activity and improving pre-contraction and QoL in postmenopausal women with SUI. | 4 weeks | BFB + PFMT | 2 sessions per week (T: 8 sessions) | ICIQ | PFMT, with and without BFB, is associated with increased FM, electromyographic activity, PFM pre-contraction and improved QoL in postmenopausal women with SUI (p < 0.0001). |

| 5. Bezerra et al 2020 | n = 32 Women ≥45 - ≤ 70 Years | Evaluating PFMT + GT in improving PFM strength, urinary loss and perceived improvement in women with MUI | 8 weeks | PFMT vs PFMT + GT | Twice a week (T: 8 weeks) | PFM strength evaluation by manometry, ICIQ-SF, urinary symptoms | There were no significant differences between the groups. Both treatments were effective for MUI symptoms. Increase in perceived improvement according to women's feedback/description. |

| 6. Dumoulin et al 2017 | n = 364 Women ≥60 Years | Determining whether PFMT in women > /+60 years + UUI or MUI is not significantly less effective, sustainable and affordable than individual PFMT | 12 months | PFMT in group vs individual | Weekly sessions (T: 12 weeks) | Adherence, urinary symptoms, severity and treatment of SUI, muscle function, QoL in both moments | A group-based approach is no less effective than individual PFMT (p < 0.05) and is more economical. Better perceived improvement in symptoms and QoL. |

| 7. Dumoulin et al 2020 | n = 362 Women ≥60 Years | Evaluate the effectiveness of group PFMT compared to individual PFMT on UI in elderly women | 12 months | PFMT in group vs individual | Weekly sessions (T: 12 weeks) | Urinary symptoms, severity and treatment, resolution of UI, muscle function, QoL in the 3 moments | A group-based approach is no less effective than individual PFMT in SUI and MUI (p < 0.05). |

| 8. Fitz et al 2017 | n = 72 Women ≥18 Years | Evaluate whether BFB + PFMT increases exercise frequency in women with SUI | 9 months | BFB + PFMT | 3 months | Adherence, urinary symptoms, severity and treatment of SUI, muscle function, QoL in both moments | Both treatments improved muscle function and QoL similarly (p < 0.005). |

| 9. Hagen et al 2020 | n = 600 Women ≥ 18 Years (±48) | To evaluate the efficacy of PFMT + BFB or PFMT alone for stress or mixed urinary incontinence in women | 6, 12, 24 months | BFB + PFMT | 6 sessions (T: 16 weeks) | Self-reported severity of UI; Women's perception of improved QoL | No significant differences in UI severity between groups of PFMT + BFB and PFMT alone. Frequent use of BFB with PFMT should not be recommended. |

| 10. Hoffman et al 2017 | n = 123 Women ≥27 Years | Evaluate long-term effects of using app with PFMT for SUI | 24 months | PFMT with app | 3 months | ICIQ-LUTSqol, ICIQ‐SF | Self-management of SUI with an app had significant (p < 0.001) and clinically relevant long-term results - recommended as first-line treatment. |

| 11. Hwang et al 2019 | n = 342 Women ≥18 Years | To evaluate the effects of TES (EasyK7) + PFMT to improve the parameters (strength, power and endurance) of PFM and sexual function and to identify the correlation between the increase in PFM parameters and sexual function after 8 weeks of training using TES in women with SUI. | 8 weeks | TES in a sitting position | 5 to 6 days per week (T: 8 weeks) | PFM parameters and sexual function (perineometer and FSFI) | TES in a sitting position showed a beneficial effect on sexual function in women with SUI (p = 0.006), and consequently on QoL. |

| 12. Jha et al 2017 | n = 114 Women ≥18 Years | To clinically evaluate the cost-effectiveness of electrical stimulation + PFMT compared to PFMT alone in women with UI and sexual dysfunction | 36 months | Electrical stimulation + PFMT | 30 sessions, with 4 to 6 weeks apart | PISQ-31 | In women with UI + sexual dysfunction, PFMT is beneficial in improving overall sexual function (p < 0.05). However, no training is beneficial over another. |

| 13. Jose-Vaz et al 2020 | n =130 Women ≥18 Years | Check the best technique to improve SUI symptoms: abdominal-hypo technique or PFMT | 12 weeks | PFMT vs abdominal-hypo technique | 2 sessions per week (T: 12 weeks) | QoL, ICIQ-SF, FM strength evaluation by MOS | With regard to SUI symptoms, impact on QoL and PFM function, both groups showed improvement, but PFMT was superior to abd-hypo among all of them (p < 0.05). |

| 14. Lausen et al 2018 | n = 73 Women ≥18 Years | To provide preliminary information on the efficacy of modified Pilates as an adjunct to PFMT for UI and to test the feasibility of an RCT project | 5 months | Modified Pilates training program and PFMT | 6 sessions per week | Self-reported UI, QoL and self-esteem, qualitative interviews | Modified Pilates classes can positively influence attitudes towards exercise, diet and well-being (p < 0.05). A definitive RCT is feasible but will require a large sample size for clinical practice purposes. |

| 15. Marques et al 2019 | n = 40 Women ≥18 Years | To evaluate the effectiveness of PFMT + training of the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius and hip adductor versus PFMT alone in the treatment of SUI | 10 weeks | TMPP + training to strengthen the hip muscles | 20 sessions per week (T:10 weeks) | Frequency of urine loss; PFM muscle strength, Ortiz and Oxford; QoL at both moments (KHQ and ICIQ-SF) | The hip muscle strengthening training group showed a significant decrease in the frequency of daily losses (p < 0.001), with no significant differences between the groups for QoL or PFM evaluation. |

| 16. Orhan et al 2018 | n = 48 Women ≥18 Years | To assess whether VTT + PFMT is more effective than PFMT alone for the treatment of SUI | 12 weeks | VTT + PFMT vs PFMT alone | 5 days per week (T:12 weeks) | Urinary symptoms, muscle function, QoL | PFMT with and without VTT exercises with similar efficacy on SUI symptoms and QoL. |

| 17. Ptak et al 2019 | n = 137 Women ≥18 Years (±53) | To assess the impact of PFMT alone and combined PFMT + Trans-abd training on the QoL of patients with UI, in relation to the number of vaginal deliveries. | 12 weeks | PFMT + TrA | 4 sessions per week (T: 12 weeks) | QoL and ICIQ-LUTSqol | Both PFMT + TrA and PFMT alone improve the QoL of women with UI (p < 0.05). However, PFMT + TrA is more effective. PFMT + TrA better results in multiparous women than PFMT alone (p < 0.001). |

| 18. Sigurdardottir et al 2019 | n = 84 Women ≥18 Years | Evaluate the effects of PFMT in the immediate postpartum period on UI and FI and associated after-effects, as well as PFM strength and endurance | 12 months | BFB + PFMT | 12 sessions per week | Muscle function, urinary symptoms | Significant improvements in postpartum UI with PFMT (p = 0.03), as well as the perception of discomfort (p = 0.005). |

| 19. Weber-Rajek et al 2020 | n = 128 Women ≥18 Years | To evaluate the efficacy of PFMT and extracorporeal magnetic innervation (NeoControl) in the treatment of UI in women with SUI. | 12 weeks | ExMI (NeoControl) vs PFMT | 3 sessions per week (T: 4 weeks) | KHQ | PFMT + ExMI proved to be an effective method for SUI in women. Improvement in physical and psychosocial aspects (no statistical significance). |

BFB - Biofeedback; ExMI - extracorporeal magnetic innervation; GT - Game Therapy; ICIQ-LUTSqol - Incontinence Questionnaire Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Quality of Life Module; ICIQ-SF - International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form; KHQ - King’s Health Questionnaire; MOS - Modified Oxford grading System; MS - Muscle Strength; MUI - Mixed Urinary Incontinence; PF - Pelvic Floor; PFM - Pelvic Floor Muscles; PFMT - Pelvic Floor Muscle Training; PISQ - 31 - Prolapse and Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire; QoL - Quality of Life; RCT - Randomized Controlled Trial; SUI - Stress Urinary Incontinence; TES - Transcutaneous Electrical Stimulation; TrA - Training of Transversus Abdominus Muscle; UI - Urinary Incontinence; UUI - Urge Urinary Incontinence; VTT - Vaginal Tampon Training.

Table 2 Methodological quality of the analysed studies

| References | Study design | PEDro | Conflict of interests | Score | ||||||||||

| E | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | ||||

| 1. Abreu et al 2017 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | no | 10 |

| 2. Asklund et al 2017 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | - | + | - | NA | NA | + | - | + | + | no | 5 |

| 3. Belushi et al 2020 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | no | 10 |

| 4. Bertotto et al 2017 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | + | no | 8 |

| 5. Bezerra et al 2020 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | no | 10 |

| 6. Dumoulin et al 2017 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | NA | no | 9 |

| 7. Dumoulin et al 2020 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | no | 10 |

| 8. Fitz et al 2017 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | no | 6 |

| 9. Hagen et al 2020 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | no | 10 |

| 10. Hoffman et al 2017 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | + | + | - | NA | NA | + | - | + | + | no | 6 |

| 11. Hwang et al 2019 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | + | + | + | NA | NA | + | + | + | + | no | 8 |

| 12. Jha et al 2017 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + | no | 9 |

| 13. Jose-Vaz et al 2020 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | no | 9 |

| 14. Lausen et al 2018 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | + | no | 8 |

| 15. Marques et al 2019 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | no | 10 |

| 16. Orhan et al 2018 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | + | no | 6 |

| 17. Ptak et al 2019 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | no | 6 |

| 18. Sigurdardottir et al 2019 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | no | 10 |

| 19. Weber-Rajek et al 2020 | RCT Parallel group | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | no | 10 |

RCT - Randomized Controlled Trials; Eligibility criteria (this item does not count towards the final score); 2. Random allocation; 3. Concealed allocation; 4. Comparability; 5. Participant blinding; 6. Therapist blinding; 7. Evaluator blinding; 8. <15% dropout; 9. Intention-to-treat analysis; 10. Statistical comparisons between groups; 11. Statistical measures of variability; NA - Not applicable

3. Discussion

This systematic review provided a comprehensive description of pelvic rehabilitation methodologies in promoting QoL in women with UI and highlighted the results related to PFMT.

Despite the heterogeneity in the assessment measures used to evaluate urinary symptoms, all studies demonstrated a reduction in the amount of involuntary urine loss, a decrease in the frequency of UI, an improvement in QoL in the PFMT groups following the intervention, and a significant increase in pelvic floor muscle (PFM) strength in the intervention groups before and after PFMT.

Sigurdardottir et al. (2019) evaluated PFMT in the postpartum period and concluded that PFMT reduces the rate of UI and discomfort present in the postpartum phase. The strength and endurance of the PFM also increased regardless of whether they were performed individually or in groups; this improvement appears to be related to the physical contact with the physiotherapist. Teaching and assessing the contractility of the PFM were included to ensure correct performance, resulting in improved body awareness, structural support of the pelvic organs, and the ability to perform quicker automatic contractions of the PFM.

The study by Hwang et al. (2019) evaluated potential improvements from an 8-week program of transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TES) on the strength parameters of the pelvic floor and sexual function in women with UI. The outcome was an increase in PFM strength and also in the domain of sexual function improvement attributed to enhanced stimulation of the PFMs. The increased contractions of the PFMs and blood flow necessary during sexual activity, along with a decrease in fear of dyspareunia and urinary loss during intercourse, enable women to regain desire, arousal, and sexual satisfaction.

Jha et al. (2017) also included in their protocol PFMT combined with electrical stimulation over 36 months, but no statistically significant differences were found compared to the group that performed isolated PFMT.

In the training programs by Dumoulin et al. (2020), individual versus group PFMT showed similar efficacy for all evaluated criteria (muscle function, UI treatment, and QoL), except for sexual issues associated with lower urinary tract symptoms. For these authors, the group approach allows for a rapid increase in the number of women treated with PFMT and makes access easier. Similarly, Dumoulin et al. (2017) noted that the impact of group PFMT is positive compared to individual PFMT sessions regarding the accessibility of continence care for women, being equally effective and more economical.

Other studies that combined biofeedback (BFB) with PFMT (Bertotto et al., 2017; Fitz et al., 2017; Hagen et al., 2020) concluded that after 24 months, comparing women who underwent BFB in a clinical context and PFMT at home with those who only performed PFMT, improvements in UI were observed in both groups, indicating that supervised and protocolized PFMT with or without BFB provides benefits.

Improvements in muscle strength and EMG activity were reported in the PFMT group with BFB, particularly in pre-contraction, endurance, and maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) in postmenopausal women. According to this study, adding BFB to PFMT helps women control and become aware of their activities and muscle activation, thus managing potential losses during daily life activities (Bertotto et al., 2017).

The literature shows that groups treated with BFB have greater progress in treating UI, likely due to the instruction on contraction in women assessed with low awareness of pelvic floor musculature (Castro et al., 2010) and that BFB-assisted PFMT is more effective than isolated PFMT in improving clinical symptoms, uroflowmetry parameters, and electromyographic activity during urination (EMG) (Sam et al., 2022).

In studies evaluating the effect of PFMT alongside vaginal tampon use compared to isolated PFMT, training effectiveness yielded similar results between the two training types regarding PFM strength and endurance, UI, and QoL. The progression was more rapid in the PFMT group with the use of a vaginal tampon. The innovation of the study was the use of a vaginal tampon in PFMT instead of vaginal cones, where the training involved pulling the tampon, thus rendering the weight of the vaginal cone ineffective (Orhan et al., 2018).

Results from game therapy showed improvement in symptoms of urge incontinence, however, associating a game-form therapy with PFMT did not demonstrate better results than isolated PFMT (Bezerra et al., 2020).

To compare the effects of PFMT with the abdomen-hypopressive technique in reducing urinary loss in women with UI, a reduction in symptoms was observed both in women who performed PFMT with the abdomen-hypopressive technique and those who only performed PFMT.

PFMT was superior to the abdomen-hypopressive technique in muscular parameters, symptom reduction of SUI, and QoL improvement. However, the reduction was significantly greater in women undergoing PFMT (Jose‐Vaz et al., 2020). Other studies also corroborate better results from PFMT (Dumoulin et al., 2017) due to the fact that the abdomen-hypopressive technique does not directly activate the contraction of the PFMs.

Studies evaluated the impact of isolated PFMT versus PFMT combined with transverse abdominal muscle (trA) activation on QoL in women with UI concerning the number of childbirths, showing that PFMT was similar for both groups. Both training types yielded positive results; however, synergistic training of the PFMs with the trA muscle was more effective in muscle parameters and QoL (Ptak et al., 2019). Other authors reported that simultaneous contraction of the trA and PFMs promotes continence (Junginger et al., 2010).

For the efficacy of dynamic lumbar-pelvic stabilization exercises in treating women with UI, compared to isolated PFMT, a similar PFMT program was implemented in both groups, and the authors concluded that there were no statistical differences in the severity of losses between the two groups. However, 90 days post-intervention, the experimental group showed a reduction in the frequency of losses and an improvement in QoL (Abreu et al., 2017).

In another study, the authors investigated the effect of strengthening exercises for the PFMs and hip muscles (adductors and abductors, gluteus maximus, and medius) compared to the isolated strengthening of the PFMs in treating SUI. According to the results, there were no significant differences between the two groups regarding functional assessment of the PFMs, perineometry, and voiding diary, as well as QoL. Thus, hip exercise training did not translate to greater strengthening of the PFM. However, the important factor of this training was the increased synergy of the pelvic muscles due to the anatomical relationship of the hip muscles with the PFMs, thus contributing to the continence mechanism and greater efficacy of physiotherapy in treating UI (Marques et al., 2019).

In the same line of training, authors like Lausen et al. (2018) associated the positive effects of modified Pilates training with PFMT in treating UI. These benefits may have arisen from participation in classes that positively influenced attitudes toward exercise, diet, and well-being. In women with mild urinary loss symptoms, the advantage of performing modified Pilates training lies in improving self-esteem, reducing social embarrassment, lowering the impact on daily living activities, and improving personal relationships.

Participation in PFMT is supported by the Cochrane review, which supports the current grade A recommendation for PFMT as a first-line treatment for women with UI (Cacciari et al., 2019).

Regarding studies with long-term follow-up, Asklund et al. (2017) and Hoffman et al. (2017) evaluated the effects of a PFMT program using a mobile application in women with SUI, yielding significant and clinically relevant results that could serve as a first-line treatment for women with UI concerning long-term follow-up (Hoffman et al., 2017).

In terms of QoL, studies have shown improvements when women are integrated into PF physiotherapy programs either individually or in groups; however, women participating in group PFMT report a better perception of improvement in urinary symptoms and QoL (Abreu et al., 2017; Dumoulin et al., 2020; Dumoulin et al., 2017; Lausen et al., 2018).

Similar results were obtained regarding improvements in QoL in treating UI in both the group receiving extracorporeal magnetic innervation (ExMI) and the group receiving PFMT, both in terms of the severity of UI and emotions, as well as social limitations. However, PFMT as a treatment for UI has fewer contraindications than therapy by ExMI (Weber-Rajek et al., 2020).

Limitations

The variety and array of interventions, including techniques, procedures, and protocols in PF physiotherapy, as well as potentially smaller sample sizes, may not provide conclusive data regarding the most effective intervention. It is also worth mentioning the subjectivity of certain assessment instruments that may have influenced the study outcomes.

Conclusion

After conducting this study, it can be concluded that PF physiotherapy intervention, utilizing PFMT in women with UI, should be considered an effective treatment, demonstrating promising results in increasing PFM strength, reducing involuntary urine loss, and improving QoL.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, E.M., T.P. and R.V.; data curation, E.M.; formal analysis, T.P. and P.P.; funding acquisition, E.M.; investigation, E.M., T.P. and P.P.; methodology, E.M., F.S., P.P. and R.V.; project administration, E.M. and R.V.; resources, E.M. and T.P.; software, E.M.; supervision, E.M., T.P., P.P. and R.V.; validation, E.M., T.P. and R.V.; visualization, E.M., T.P., F.S., P.P. and S.V.; writing-original draft, E.M. and T.P.; writing-review and editing, E.M., T.P., F.S., P.P., S.V and R.V.