Introduction

Over the last few years, research in nursing leadership has shown a growing interest, resulting in contributions to the definition of strategies that allow responding to the emerging challenges that healthcare organizations face. The scientific literature is consensual in highlighting the positive impact of leadership on the quality of healthcare and personal outcomes (Cummings et al., 2021). Different studies clarify the role of nursing leadership in professional satisfaction (Specchia et al., 2021), nurse retention (Cardiff et al., 2023) and levels of stress and burnout (Wei et al., 2020), confirming that effective leadership practices are structural to organizational success.

1. Theoretical framework

The current complexity of healthcare and the challenges posed by increasingly demanding and constantly changing practice environments result in the need for leadership at the level of micro, meso and macro systems, meaning that nurses are challenged to demonstrate a characterized professional practice leadership behaviors and practice based on interdisciplinary collaboration (World Health Organization, 2021). Watson et al. (2021) consider it imperative that nurses develop skills that enable leadership at all levels, as they play a foundational role in the provision of care and have a high potential to influence the person's results. By demonstrating leadership behaviors at the level of clinical practice, nurses assert themselves as partners in defining care, contributing to the construction of innovative and structured healthcare models (Watson et al., 2021).

Clinical leadership in nursing emerges as a response to the need to define practice environments where interprofessional collaboration prevails and the abandonment of vertical leadership, as strategies that allow the provision of integrated care and equitable access to health care (National Academies of Sciences, 2021). It is an emerging concept in literature (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2018), which concerns the demonstration of informal leadership skills and behaviors by nurses in clinical practice (Isler et al., 2021). Duprez et al. (2023) characterize clinical leadership in nursing as participatory or transformational, which integrates principles such as collaboration, coordination, defending the person and the ability to make autonomous decisions (Simmons et al., 2020).

The clinical nurse leader is one who has the potential to influence and coordinate the person, family, peers and other team members, who asserts himself as a partner in defining care and who accepts the responsibility of leading (Chávez & Yoder, 2015; International Council of Nurses, 2017). He demonstrates experience and clinical skills, ability to build teams and relationships, and reveals qualities that inspire excellence in care (Isler et al., 2021).

Based on a culture of interdisciplinary collaboration, the clinical leader aims to lead processes of continuous improvement of practices, namely through increasing the quality and safety of care, evidence-based practice and promoting efficiency in the integration of interdisciplinary contexts and practices. (Bender et al., 2019). Watson et al. (2021) highlight clinical leadership behaviors, highlighting their importance for effective communication within the healthcare team and for the provision of high-quality care.

Clinical leadership in nursing incorporates the social and ethical responsibility of nurses (International Council of Nurses, 2017), and it is essential that they assume these competencies as an integral part of professional practice behaviors (Jones, 2020). Health organizations are expected to define strategies that facilitate individual participation and promote leadership in terms of direct care provision (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2018).

Despite being recognized as holders of knowledge and leadership skills, nurses do not always legitimize their role as leaders (Grindel, 2016; Jones, 2020). In clinical practice, the delegation of competencies or the presence of inconsistent leadership behaviors are common, resulting from factors inherent to the clinical practice environment or individual characteristics. Xu et al. (2022) concluded that the training deficit and the perception that leadership behaviors are exclusive to formal leaders are determinants that hinder clinical leadership. Other factors, such as the time needed to provide care, the perception of the lack of power and skills to exercise the role of leader, and the desire not to assume more responsibility or a greater volume of work were highlighted by Grindel (2016), which makes it imperative to define and implement organizational strategies that reverse these determinants.

Encouraging and promoting clinical leadership behaviors ensures the advancement of nursing as a profession and discipline (Patrick et al., 2011), has significance in organizational success (Cardiff et al., 2023; Specchia et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2020) and translation into the results of nursing care (Mianda & Voce, 2018). At the microsystem level, nursing leadership contributes to the global reform of healthcare (Watson et al., 2021), and practice environments can facilitate or not the nurse's role as a clinical leader (Isler et al., 2021).

In the context of healthcare organizations, scientific literature expresses the relationship between clinical leadership in nursing and retention and job satisfaction, the improvement of nursing practice environments (Bender et al., 2019) and the quality and safety of care (Watson et al., 2021). However, despite the recognition of the positive impact of the clinical nurse leader role on the person's outcomes, empirical investigation of leadership behaviors has focused on formal leadership contexts and their influencing variables (Watson et al., 2021). Therefore, there remains a gap regarding the investigation of clinical leadership practices and behaviors in nursing, which is why the systematization of existing scientific evidence in this area is useful for designing studies that fill this gap. Knowledge mapping may also contribute to the definition of strategies that facilitate the acquisition of skills and the development of clinical leadership behaviors in healthcare organizations and support the definition of leadership interventions and programs at the level of clinical practice.

A preliminary research was carried out in the databases Joanna Briggs Institute Database of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Open Science Framework, without identifying any published or registered literature review aimed at systematizing knowledge relating to behaviors of clinical leadership in nursing. Some reviews were identified that refer to leadership interventions and strategies. However, these present some particularities that may limit a comprehensive mapping, since the research was limited to a specific context (Guibert‐Lacasa & Vázquez‐Calatayud, 2022; Iraizoz-Iraizoz et al., 2023).

Based on the above, it is considered pertinent to carry out a scoping review with the objective of mapping the scientific evidence regarding the behaviors of the clinical nurse leader and the strategies that promote clinical leadership in nursing in healthcare organizations.

2. Methods

The recommendations of the Joanna Briggs Institute for scoping reviews were followed (Peters et al., 2024). To organize the information, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses - PRISMA (Page et al., 2021) model was used, basing the writing of the study on the guidelines of the PRISMA for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist. (Tricco et al., 2018). The protocol was registered on the Open Science Framework platform with the registration https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2SQMX.

2.1 Search strategy

To define the review question, the PCC strategy (population, concept, context) (Peters et al., 2024) was used, considering P - nurses, C - clinical leadership behaviors, strategies that promote the development of clinical leadership in nursing and C - health organizations. The objective was to answer the review question “What are the behaviors of the clinical nurse leader and what strategies do promote clinical leadership in nursing in healthcare organizations?”.

A three-step research strategy was designed and implemented on January 12, 2024. An initial limited research was carried out in CINAHL (EBSCO/Host) to identify and analyze the words in the text and the indexing terms contained in the title and abstract of articles of interest, using the strategy “clinical leadership” ENT#091;All fieldsENT#093; AND “nurs*” ENT#091;All fieldsENT#093; AND “behavior*” ENT#091;All fieldsENT#093; OR “strateg*” ENT#091;All fieldsENT#093;.

In the second stage, a complete research was carried out in the databases MEDLINE Complete (via EBSCOHost), CINAHL Complete (via EBSCOHost), Scopus and Web of Science, to identify published studies, and in ProQuest (via Web of Science) and Repository Open Access Scientific Institute of Portugal, to identify unpublished studies. The indexing terms and keywords were combined using the Boolean operators AND and OR, and the research strategy was adapted to each source of information, as exemplified in Table 1. The “*” truncation was used to enhance the research by creating new variations from the same root word.

Table 1 Research strategy for the Web of Science database

| Search | Query terms | Retrived articles |

| #1 | (((((((((((TS=(clinical leader*)) OR TS=(informal leader*)) OR TS=(clinical nurs* leader*)) OR TS=(CNL)) OR TS=(frontline leader*)) OR TS=(registered nurse* clinical leader*)) OR TS=(staff nurse clinical leadership)) OR TS=(clinical practice leader*)) OR TS=(nurs* self-leadership)) OR TS=(charge nurse leadership)) OR TS=(nurs* practitioner leader*)) OR TS=(nurs* clinicians leadership) and Open acess and Article (Document Type) and English or Spanish or Portuguese (Languages) | 9702 |

| #2 | (((((((TS=(clinical leader* behavior*)) OR TS=(clinical leader* behaviour*)) OR TS=(TI clinical leader* attitude*)) OR TS=(clinical leader* capabilit*)) OR TS=(cooperative behavior*)) OR TS=(cooperative behavior*)) OR TS=(clinical leader* skill*)) OR TS=(clinical leader* abilit*) and Open acess and Article (Document Type) and English or Spanish or Portuguese (Languages) | 11407 |

| #3 | ((((((TS=(leadership strateg*)) OR TS=(leadership method*)) OR TS=(leadership technique*)) OR TS=(leadership intervention*)) OR TS=(leadership development)) OR TS=(leadership training)) OR TS=(leadership program*) and Open acess and Article (Document Type) and English or Spanish or Portuguese (Languages) | 30127 |

| #4 | (((((((ALL=(healthcare unit*)) OR ALL=(healthcare organization*)) OR ALL=(healthcare service*)) OR ALL=(healthcare institution*)) OR ALL=(healthcare setting*)) OR ALL=(nurs* practice environment*)) OR ALL=(nurs* work environment*)) OR ALL=(healthcare establishment) and Open acess and Article (Document Type) and English or Spanish or Portuguese (Languages) | 98813 |

| #5 | #2 OR #3 | 40015 |

| #6 | #1 AND #4 AND #5 | 1242 |

The third stage concerns the analysis of the reference lists of articles included in the scoping review, in order to identify additional relevant studies. Articles of interest identified in the reference lists were conditionally included in the list of articles to be analyzed. Given the need to obtain unpublished information, it was established contact with the authors of the studies.

2.2 Inclusion criteria

Studies whose population were nurses in healthcare organizations were considered, which demonstrate leadership behaviors in clinical practice or which report strategies that promote clinical leadership in nursing. The research was not limited according to the sociodemographic or professional variables of the sample, the typology of the clinical context or the variables characterizing the health organization.

Studies related to the investigation of formal leadership, such as that exercised by nurse managers, nurses in management roles or nursing directors, and studies carried out on nursing students were excluded. In studies whose sample includes different health professionals, only the results relating to nurses in clinical practice were considered.

Quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods studies were included, with peer review and published in Portuguese, English or Spanish. Theoretical articles, opinion texts, editorials and secondary studies were excluded.

2.3 Selection and eligibility of evidence sources

The retrieved articles were imported into the Rayyan Intelligent Systematic Review® software (Cambridge/United States of America, Doha/Qatar), which allowed them to be cataloged and as well as eliminate duplicate references. To select the studies, two independent reviewers blindly read and analyzed the title and abstract, considering the defined eligibility criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by recruiting a third independent reviewer. In dubious cases, the study was provisionally included in the list of articles to be analyzed, deciding whether to include it after reading and analyzing the full text.

The stage of reading and analyzing the full text of articles of interest was carried out by two independent reviewers, excluding studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria. The relevance of studies from the analysis of the list of references of included articles was decided based on reading the title and abstract. For these studies, the analysis of the full text and the decision to include it in the literature review replicated the evaluation procedure for articles resulting from the research strategy.

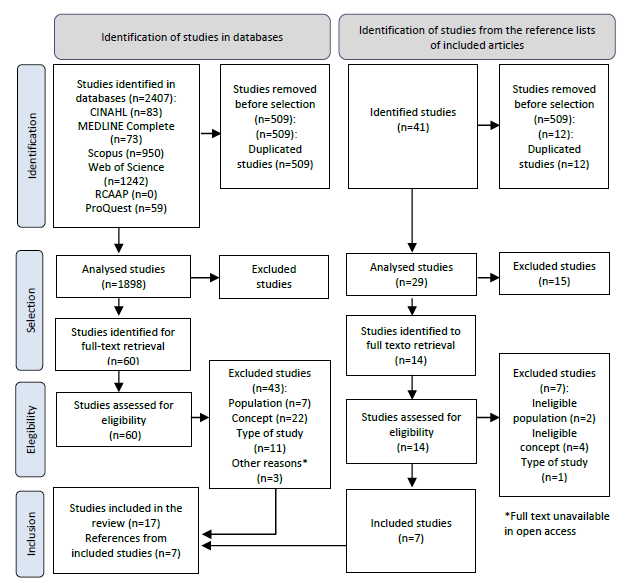

The research results and the selection process are represented in a flow diagram adapted from PRISMA-ScR (Page et al., 2021). Considering the guidelines for preparing a scoping review, the methodological quality of the included studies was not assessed (Page et al., 2021). The articles included in the literature review were identified with an alphanumeric code (An) and organized in chronological order, from the most recent to the oldest.

2.4 Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction was carried out by two independent reviewers who cataloged the data in an instrument built for this purpose. In the first five articles, this step was carried out in parallel by the two reviewers, which proved to be enough to guarantee the clarity and consistency of the extracted data. To resolve disagreements, a third reviewer was recruited.

The extracted data is presented in a diagrammatic and tabular format, accompanied by a narrative summary that highlights the essential information. To systematize data relating to nurses' leadership behaviors in clinical practice, the Integrative Model of Leadership Behaviors (Behrendt et al., 2017) was used as a reference, so these are categorized into task-oriented behaviors and relationship-oriented. Task-oriented behaviors are those that contribute to the achievement of goals. Relationship-oriented behaviors integrate attitudes that provide resources to followers, allowing them to direct their efforts towards task-oriented processes.

To organize the strategies that promote clinical leadership, a content analysis of the extracted data was carried out and its categorization into strategies related to the nurse, the team, the health organization and entities external to the health organization.

3. Results

Study selection

From the research strategy, 2407 references emerged, of which 1898 were selected for analysis of the title and abstract. 60 articles were identified for full-text evaluation, of which 17 were included in the scoping review. Of the analyzed articles in full text, 43 were excluded because they were not available in open access (n=3) or because they did not meet the inclusion criteria with regard to the population (n=7), the concept (n=22) or to the type of study (n=11).

From the analysis of the bibliographic references of the included articles, 14 full-text studies were retrieved. Of these, using similar inclusion and exclusion criteria, 7 were included in the scoping review, making a total of 24 studies (Figure 1).

Characteristics of studies and participants

The studies included were developed between 2003 and 2023. Qualitative studies predominate (Amestoy et al., 2009; Burns, 2009; Carney, 2009; Connelly et al., 2003; Cook & Leathard, 2004; De Kok et al., 2023; Holmgren et al., 2022; Olsen, 2019; Lamb et al., 2018; 2022; van Kraaij et al., 2020) and carried out in hospitals (AL-Dossary et al., 2016; Amestoy et al., 2009; Connelly et al., 2003; Cook & Leathard, 2004; De Kok et al., 2023; Hart et al., 2014; Holmgren et al., 2022; Lamb et al., 2018; Mrayyan et al., 2023; , 2006a; Supamanee et al., 2011; Hafsteinsdóttir, 2022; van Kraaij et al., 2020). Studies carried out in the United Kingdom (Burns, 2009; Cook & Leathard, 2004; Singhal et al., 2021; Stanley, 2006a, 2006b), United States of America (Connelly et al., 2003; Hart et al., 2014; Sherman et al., 2011), Ireland (Carney, 2009; Elliott et al., 2013; Higgins et al., 2014), Netherlands (De Kok et al., 2023; van Dongen & Hafsteinsdóttir, 2022), Canada (Lamb et al., 2018; Patrick et al., 2011), Jordan (Mrayyan et al. ., 2023), South Africa (Mtsoeni et al., 2023), Iran (Razavi et al., 2022), Sweden (Holmgren et al., 2022), Germany (van Kraaij et al., 2020), Norway (Husebø & Olsen, 2019), Saudi Arabia (AL-Dossary et al., 2016), Thailand (Supamanee et al., 2011) and Brazil (Amestoy et al., 2009) (Table 2). Different research designs were used, which included semi-structured interviews (Burns, 2009; Carney, 2009; Connelly et al., 2003; Cook & Leathard, 2004; De Kok et al., 2023; Elliott et al., 2013 ; Higgins et al., 2014; Lamb et al., 2018; 2023; Razavi et al., 2022; van Dongen & Hafsteinsdóttir, 2022; et al., 2016; Hart et al., 2014; Mrayyan et al., 2023; Patrick et al., 2011; Sherman et al., 2011; Holmgren et al., 2022; Supamanee et al., 2011) and non-participant observation (Cook & Leathard, 2004; Elliott et al., 2013; Higgins et al., 2014; Husebø & Olsen, 2019; Singhal et al., 2021). The sample size varied between four (Cook & Leathard, 2004) and 480 participants (Patrick et al., 2011), with the majority of studies being carried out on samples made up of nurses in clinical practice (AL-Dossary et al., 2016;Cook & Leathard, 2009; 2004; De Kok et al., 2023; Mtsoeni et al., 2023; 2011;Stanley et al., 2011; 2006a, 2006b; van Dongen & Hafsteinsdóttir, 2022; van Kraaij et al., 2020). Four studies included multidisciplinary team members (Elliott et al., 2013; Higgins et al., 2014; Husebø & Olsen, 2019; Razavi et al., 2022) and two included nurses in management roles and nurses in clinical practice (Connelly et al., 2003; Supamanee et al., 2011).

Table 2 Main characteristics of the studies

| Suty ID | Country Language | Type os study Data collection procedure | Health organization Sample | Objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 (Mrayyan et al., 2023) | Jordan English | Quantitative study Questionnaire (Stanley’s Clinical Leadership Scale) | Hospital Convenience sample 296 nurses carrying out clinical practice | Research the attributes and skills of clinical leadership in nursing and the actions that effective clinical nurse leaders can take |

| A2 (De Kok et al., 2023) | Holland English | Qualitative study Semi-structured group interview | Hospital Convenience sample 52 nurses carrying out clinical practice | Understand how nurses perceived the contributions of the Dutch Excellent Care Program, the development of nurses' leadership and their ability to positively influence their work environment |

| A3 (Mtsoeni et al., 2023) | South Africa English | Descriptive, qualitative study Phenomenological interview | Hospital Convenience sample 5 newly graduated nurses practicing clinical practice | Explore and describe the lived experiences of newly qualified critical care nurses |

| A4 (van Dongen & Hafsteinsdóttir, 2022) | Holland English | Descriptive, qualitative study Semi-structured interview | Hospital Convenience sample 12 doctorate nurses carrying out clinical practice | Explore leadership experiences and the influence of leadership on the career development of doctoral nurses working in hospitals |

| A5 (Razavi et al., 2022) | Iran English | Qualitative study Semi-structured interview | Hospital Convenience sample 15 health team members with experience in teamwork, 4 of whom are nurses in clinical practice | Explore leadership behaviors from the perspective of Iranian healthcare team members |

| A6 (Holmgren et al., 2022) | Sweden English | Qualitative study Focus group | Hospital Convenience sample 12 nurses in clinical practice | Explore how charge nurses perceive their role in managing daily work and major incidents in the emergency department |

| A7 (Singhal et al., 2021) | United Kingdom English | Grounded Theory Qualitative study Non-participant observation | Hospital Convenience sample 8 nurses responsible for shift | Describe the problem-solving approaches used by shift managers and the coordination of their role with other team members |

| A8 (van Kraaij et al., 2020) | Germany English | Qualitative study Semi-structured interview | Hospital Convenience sample 18 nurses with a master's degree practicing clinical practice | Gain insight into the leadership roles of nurses in German hospital care, exploring perceptions regarding their current leadership role and differences from their previous role as a registered specialist nurse |

| A9 (Husebø & Olsen, 2019) | Norway English | Exploratory, qualitative study Non-participant observation | Hospital Convenience sample 5 nurses and 4 doctors with leadership training and in clinical practice | Explore the activities carried out by clinical leaders and identify the similarities and differences between the activities carried out by charge nurses and those carried out by emergency department doctors after completing a leadership course |

| A10 (Lamb et al., 2018) | Canada English | Descriptive, qualitative study Semi-structured interview (initial and follow-up) | Hospital Convenience sample 14 advanced practice nurses | Explore critical care advanced practice nurses' perceptions of their leadership abilities |

| A11 (AL-Dossary et al., 2016) | Saudi Arabia English | Cross-sectional, descriptive, quantitative study Questionnaire | Hospital Convenience sample 98 newly graduated nurses practicing clinical practice | To assess the impact of residency programs on the leadership skills of new Saudi postgraduate nurses who completed a residency program compared to new Saudi postgraduate nurses who did not participate in residency programs |

| A12 (Higgins et al., 2014) | Ireland English | Case study Semi-structured interview Non-participatory observation | Hospital and Primary health care Convenience sample 13 nursing directors and 21 members of the multidisciplinary team (interviews) 23 specialist nurses and advanced practice nurses (non-participated observation) of the multidisciplinary team (interviews) | Report the factors that influence the ability of clinical specialists and advanced practice nurses to perform their clinical and professional leadership roles |

| A13 (Hart et al., 2014) | United States of America English | Cross-sectional, prospective, descriptive, quantitative study Questionnaire (Self-Confidence Scale and eight leadership skills items to measure technical and non-technical skills in responding to crisis situations) | Hospital Convenience sample 148 nurses carrying out clinical practice | To explore and understand the perceived self-confidence and leadership capabilities of medical-surgical nurses as first responders in recognizing and responding to clinical deterioration prior to the arrival of an emergency team. |

| A14 (Elliott et al., 2013) | Ireland English | Case study Non-participatory observation Semi-structured interview | Non specified Convenience sample 23 specialist nurses and advanced practice nurses (non-participated observation) 41 members of the multidisciplinary team and 28 nursing directors (semi-structured interview) | To assess the role and services of clinical nurse/midwives and advanced practice nurse/midwives in Ireland |

| A15 (Patrick et al., 2011) | Canada English | Methodological study Questionnaire | Hospital Convenience sample 480 nurses carrying out clinical practice | Testing the psychometric properties of a newly developed measure of clinical leadership in nursing derived from the Kouzes and Posner Transformational Leadership Model |

| A16 (Supamanee et al., 2011) | Tailândia Inglês | Tailand English | Descriptive, qualitative study Semi-structured interview Focus group | Hospital Convenience sample 23 nurses in management positions (semi-structured interview) and 31 nurses in clinical practice (focus group) |

| A17 (Sherman et al., 2011) | United States of America English | Exploratory, descriptive, mixed methods study Questionnaire developed by the authors | Hospital Convenience sample 400 responsible nurses carrying out clinical practice | Examining the necessary leadership qualities, challenges, and factors that satisfy the roles from the perspective of the frontline nurse leader |

| A18 (Amestoy et al., 2009) | Brasil Portuguese | Exploratory, descriptive, qualitative study Focus group | Hospital Convenience sample 11 nurses practicing clinical practice | Knowing the characteristics that interfere in the construction of a nurse leader |

| A19 (Carney, 2009) | Ireland English | Qualitative study Semi-structured interview | Primary health care Convenience sample 20 public health nurses practicing clinical practice | Identifying how clinical leadership skills are perceived by public health nurses throughout their daily work and the effectiveness and consequences of such skills in the provision of primary care |

| A20 (Burns, 2009) | United Kingdom English | Qualitative study Semi-structured interview | Primary health care Convenience sample 12 nurses practicing clinical practice | Exploring in depth the concept of clinical leadership from the perspective of nurses in clinical practice to provide insight into the feelings and perceptions of nurses in clinical practice and identify the issues that arise |

| A21 (Stanley, 2006a) | United Kingdom English | Qualitative study Questionnaire (phase 1) Semi-structured interview (phases 2 and 3) | Hospital Convenience sample 188 nurses practicing clinical practice (phase 1) 42 nurses practicing clinical practice (phase 2) 8 peer-identified clinical leaders (phase 3) | Identifying who the clinical leaders are in a National Health Service hospital and explore and critically analyze the experience of being a clinical nurse leader |

| A22 (Stanley, 2006b) | United Kingdom English | Qualitative study Semi-structured interview | Not specified Convenience sample 42 nurses exercising clinical practice | Identifying who the clinical leaders are and critically analyze the experience of being a clinical leader |

| A23 (Cook & Leathard, 2004) | United Kingdom English | Descriptive, qualitative study Semi-structured interview Non-participatory observation Focus group | Hospital and Primary Health Care Convenience sample 4 nurses recognized as leaders practicing clinical practice | Identifying the attributes of the clinical nurse leader |

| A24 (Connelly et al., 2003) | United States of America English | Exploratory, qualitative study Semi-structured interview | Hospital Convenience sample 11 nurses practicing clinical practice 12 responsible nurses 10 head nurses 9 nursing supervisors | Reporting the skills required to effectively perform the role of responsible nurse |

Clinical leadership behaviors in nursing

In the studies by Razavi et al. (2022), Husebø and Olsen (2019), Higgins et al. (2014) and Elliot et al. (2013) only consider data relating to the nurse's behavior as a clinical leader. Forty-seven clinical leadership behaviors in nursing were identified (Table 3), which were categorized into task-oriented behaviors and relationship-oriented behaviors, according to the Integrative Model of Leadership Behaviors (Behrendt et al., 2017). Most of the identified behaviors are task-oriented (n=25). Two behaviors were identified in only one study (promoting continuity of care (Connelly et al., 2003) and teaching how to be a leader (Razavi et al., 2022)) and the majority (n=26) were reported in at least five studies. Regarding task-oriented behaviors, those related to clinical practice prevail (n=18).

Regarding relationship-oriented behaviors, the predominant ones are behaviors related to effective communication (AL-Dossary et al., 2016; Amestoy et al., 2009; Burns, 2009; Carney, 2009; Connelly et al., 2003; Elliott et al., 2013; Hart et al., 2014; Husebø & Olsen, 2019; Lamb et al., 2018; Mrayyan et al., 2023; 2006b, 2006a; Supamanee et al., 2011; van Kraaij et al. , 2020), peer empowerment and professional development (Carney, 2009; Connelly et al., 2003; Cook & Leathard, 2004; Elliott et al., 2013; Higgins et al., 2014; Lamb et al., 2018; Mrayyan et al., 2023; , 2020) and mentoring (Burns, 2009; Carney, 2009; Cook & Leathard, 2004; Elliott et al., 2013; Higgins et al., 2014; Holmgren et al., 2022; Lamb et al ., 2018; Patrick et al., 2011; Razavi et al., 2022; Singhal et al., 2021; Stanley, 2006a).

Table 3 Clinical leadership behaviors in nursing

| Task-oriented behaviors | |

|---|---|

| Resources | Manage resources (A1, A5, A7, A9, A13, A24) Taking responsibility for one's own continuing professional development (A2, A16, A19) |

| Practice environment | Dealing well with change (A1, A8, A24) Identify areas for change and develop innovative practices (A1, A2, A4, A20, A24) Improvising in new situations (A1, A6, A8, A23) Identify problems and suggest ways to solve them (A1, A2, A5, A6, A10, A12, A20, A21, A24) Implement strategies that allow for the improvement of nursing practice environments (A2, A4, A10, A20) |

| Clinical practice | Facilitate good practices in the provision of care (A1, A19) Ensure efficiency in the provision of care (Practice oriented towards managing the person's needs) (A1 A5, A8, A9, A10, A11, A12, A14, A15, A22, A24) Demonstrate autonomous decision-making capacity (A1, A2, A3, A5, A8, A12, A14, A16, A18, A19, A22, A24) Lead actions and procedures (initiative in asserting oneself as a leader) (A1, A6, A8, A12, A16, A18) Ability to influence others (influence the way clinical practice is performed) (A1, A14, A18) Being visible in clinical practice (A1, A20, A21, A22) Challenging the status quo (A2, A6, A16, A23) Demonstrate critical thinking skills (A3, A15, A16) Professional practice based on collaborative practice (A3, A5, A6, A7, A8, A13, A15, A16) Be a role model for peers (A3, A5, A6, A8, A10, A12, A14, A16, A17, A20, A21, A22) Plan, coordinate and evaluate team activities (A3, A5, A6, A9, A11, A12, A14, A17, A18, A19, A24) Delegate care and tasks based on skills, abilities and knowledge (A5, A12, A14, A16, A17, A21, A24) Develop evidence-based practice (A5, A7, A8, A10, A14 A15, A16, A19, A20, A21) Demonstrate clinical competence (A5, A8, A10, A11 A15, A16, A17, A21, A22, A24) Promote improvement in the quality of care (A8, A10, A14, A16, A24) Demonstrate clinical knowledge in a specialty area (A10, A16, A18, A19, A20, A21, A22) Promote continuity of care (A24) |

| Relationship-oriented behaviors | |

| Interpersonal relationship | Valuing relationships (A1, A16, A18, A19, A21, A22) Being caring and compassionate (A1, A11, A15, A17, A20, A24) Inspire confidence (A1, A14, A16) Be accessible (A1, A16, A17, A21, A22, A24) Promote relationships with the multidisciplinary team (A3, A5, A6, A8, A16, A17, A19, A22) Manage interpersonal conflicts (A3, A5, A16, A17, A19) |

| Communication | Communicate effectively (A1, A8, A9, A10, A11, A13, A14, A15, A16, A17, A18, A19, A20, A21, A22, A24) Present ideas logically (A1, A13, A15, A20) |

| Multidisciplinary team | Work as a team to achieve shared goals (A1, A5, A10, A13, A16, A17, A21, A24) Value the role and contributions of others (A1, A15, A20) Give positive feedback (A1, A5, A15, A17, A20) Participate in the training and professional development of peers (A1, A5, A8, A10, A12, A14, A16, A17, A19, A23, A24) Provide support (A1, A5, A6, A7, A13, A16, A20, A23) Encourage initiative, innovation and peer involvement (A1, A5, A14, A19, A20, A21, A22, A24) Teaching to be a leader (A5) Guide and help peers in problem-solving (mentoring) (A5, A6, A7, A10, A12, A14, A15, A19, A20, A21, A23) |

| Values | Respect the codes of professional conduct (A1, A16, A19) Being willing to take and take risks for something you believe in (A1, A15, A17, A18, A21) Establish and maintain personal boundaries (A8, A24) |

| Organization | Influencing organizational policy (A1, A4, A8, A14) Participate in organizational decisions (A6, A8, A12, A14) Engage in organizational groups (A14, A23) Engaging peers in achieving shared goals (ability to influence) (A10, A23) |

Strategies to promote clinical leadership in nursing

From the literature review, 18 strategies that promote clinical leadership in nursing emerged (Table 4) that were categorized into strategies related to the nurse (n=3), the multidisciplinary team (n=5), the health organization (n=8) and with entities external to the health organization (n=2).

Strategies related to the nurse include defining individual plans that allow the development of clinical leadership skills (De Kok et al., 2023; Higgins et al., 2014), working on self-motivation to perform the role of clinical leader (Mtsoeni et al., 2023) and the implementation of postgraduate training (van Kraaij et al., 2020).

With regard to the multidisciplinary team, strategies have been identified that are aimed at communication (Mtsoeni et al., 2023), support in the transition to the leadership role (Connelly et al., 2003; Holmgren et al., 2022; Mtsoeni et al., 2023; van Kraaij et al., 2020), clear definition of roles (Connelly et al., 2003; Mtsoeni et al., 2023), recognition for work performed (Burns, 2009; Mtsoeni et al. , 2023; van Dongen & Hafsteinsdóttir, 2022) and guidance and mentoring for the role (Connelly et al., 2003; Holmgren et al., 2022; Husebø & Olsen, 2019; Mtsoeni et al., 2023; van Kraaij et al., 2020).

Ten studies identified strategies related to healthcare organization. The definition and implementation of leadership training programs was the strategy cited in the largest number of studies (Connelly et al., 2003; Cook & Leathard, 2004; De Kok et al., 2023; Holmgren et al., 2022; Husebø & Olsen, 2019).

Strategies related to entities external to the organization were identified in two studies and concern support for obtaining additional training (Holmgren et al., 2022) and the opportunity to define partnerships that promote networking and the definition of strategic alliances (Higgins et al., 2014).

Table 4 Strategies to promote clinical leadership in nursing.

| Strategies to promote clinical leadership in nursing | |

|---|---|

| Nurse-related strategies | Defining an individual plan to cement leadership skills in clinical practice (A2, A12) Work on intrinsic self-motivation to perform the role of leader (A3) Carrying out postgraduate training (A8) |

| Strategies related to the multidisciplinary team | Strong communication between team members (A3) Support from peers, middle management, nursing management and medical staff in transitioning to the role of shift leader/manager (A3, A6, A8, A24) Clear definition of shift manager duties (A3, A24) Recognition of the role of clinical leader and the work performed (A3, A4, A20) Peer clinical supervision (role guidance and mentoring) (A3, A4, A6, A9, A24) |

| Strategies related to health organization | Definition and implementation of leadership training programs (A2, A6, A9, A13, A23, A24) Defining leadership programs with immersion in real scenarios (A23, A24) Nurses' involvement in clinical governance (A2, A8) Recognition of the role of clinical leader and the work performed (A3, A8) Visibility and incentive to perform the role A3) Practice environment conducive to career development (A4, A8) Promotion of nursing research (A4) Defining and implementing transition programs from academia to clinical practice (A11) |

| Strategies related to entities external to the healthcare organization | Support from local, regional and national entities to obtain additional training (A6) Networking opportunities and definition of strategic alliances (A12) |

4. Discussion

Clinical leadership presents itself as an emerging and context-dependent concept that does not yet have a widely accepted definition. In a concept analysis, Chávez and Yoder (2015) refer to clinical leadership in nursing as the use of informal leadership behaviors by nurses during the direct provision of care, with the aim of leading the multidisciplinary team to achieve common goals. The literature review carried out supports this definition, by showing that the clinical nurse leader must have the ability to influence others (Amestoy et al., 2009; Elliott et al., 2013; Mrayyan et al., 2023), challenging the status quo. (Cook & Leathard, 2004; De Kok et al., 2023; Holmgren et al., 2022; Supamanee et al., 2011) and demonstrating skills in planning, coordinating, and evaluating team activities (AL-Dossary et al., 2016; Elliott et al., 2013; Higgins et al., 2014; Holmgren et al., 2022; ., 2023; Razavi et al., 2022; Sherman et al., 2011).

During clinical practice, nurses assume a prominent position regarding the possibility of identifying organizational inefficiencies related to practice environments, workflow and policies at the level of micro and macrosystems (Iraizoz-Iraizoz et al., 2023). They are expected to adopt behaviors that are consistent with leadership of care and change, motivating peers and other team members towards continuous improvement of the quality and safety of care and problem solving in the context of clinical practice (International Council of Nurses, 2019; Iraizoz-Iraizoz et al., 2023). It is therefore essential that nurses implement strategies that contribute to improving nursing practice environments (Burns, 2009; De Kok et al., 2023; Lamb et al., 2018; van Dongen & Hafsteinsdóttir, 2022 ), improvise in new situations (Cook & Leathard, 2004; Holmgren et al., 2022; Mrayyan et al., 2023; van Kraaij et al., 2020) and identify areas that allow the development of innovative practices towards change (Burns , 2009; Connelly et al., 2003; De Kok et al., 2023; Mrayyan et al., 2023; van Dongen & Hafsteinsdóttir, 2022) and problem solving (Burns, 2009; Connelly et al., 2003; De Kok et al., 2023; Higgins et al., 2014; Holmgren et al., 2022; Lamb et al., 2018; Mrayyan et al., 2023; Razavi et al., 2022; Stanley, 2006a).

The clinical nurse leader distinguishes himself from his peers through effective communication skills, knowledge and clinical competence (Ashour et al., 2022; Chávez & Yoder, 2015; Stanley & Stanley, 2018), demonstrating the ability to influence the multidisciplinary team, through mentoring, empowerment, participation in education and team development (Stanley & Stanley, 2018). The literature mapping showed that the clinical leader is the one who demonstrates autonomous decision-making capacity (Amestoy et al., 2009; Carney, 2009; Connelly et al., 2003; De Kok et al., 2023; Elliott et al. , 2013; Razavi et al., 2014; Mrayyan et al., 2023; Mtsoeni et al., 2023; and critical thinking (Mtsoeni et al., 2023; Patrick et al., 2011; Supamanee et al., 2011), designing and implementing care that results in improved quality and safety of care. Knowledge and mastery are vehicles for excellent clinical practice and can inspire others, contributing to the development of their skills and competencies as nurses and future clinical leaders. Advanced nursing practice, a necessary condition for exercising leadership at the level of clinical practice and a primary determinant of the quality and safety of care, requires the acquisition of clinical knowledge and skills that can support autonomy in decision-making regarding care, the capacity for reflection and critical judgment (Carvalho et al., 2022).

In a study that evaluated the association between experience and leadership skills, Alilyyani et al. (2024) showed that leadership behaviors are related to expertise and are often developed after the nurse has already positioned themselves as a leader. This fact highlights the need and relevance of defining a long-term strategic approach that facilitates the development of clinical leadership behaviors in nursing. Healthcare organizations must recognize and value the responsibility of providing support structures and resources necessary for the continued development of leadership behaviors, particularly in newly graduated nurses. In parallel, it becomes imperative that initial nursing training considers leadership in training programs, since this is a competence that is developed in a clinical but also academic context (Duprez et al., 2023). The synthesis of scientific evidence resulted in a set of strategies promoting clinical leadership in nursing, with the main mechanisms identified being the definition and implementation of training programs (Connelly et al., 2003; Cook & Leathard, 2004; De Kok et al., 2023 ; Hart et al., 2014; Holmgren et al., 2022; Husebø & Olsen, 2019) and clinical peer supervision as a guidance and mentoring strategy for performing the leader role (Connelly et al., 2003; Holmgren et al., 2022; Husebø & Olsen, 2019; Mtsoeni et al., 2023; van Dongen & Hafsteinsdóttir, 2022). These results are consistent with other studies that highlight experiential learning as an effective strategy for leadership development (Duprez et al., 2023). The definition of an individual plan that allows the cementing of leadership skills during clinical practice (De Kok et al., 2023; Higgins et al., 2014) and immersion in real scenarios (Connelly et al., 2003; Cook & Leathard, 2004) provide nurses with a safe learning environment, which allows them to develop leadership behaviors (Duprez et al., 2023).

Growth and failure, along with recognition of the role of clinical leader and the influence this can have on care outcomes and organization, can present a path that supports self-reflection and self-motivation. Duprez et al. (2023) reflect the impact of self-reflection on the development of clinical leadership behaviors in nursing, reiterating the importance of an organizational culture that allows nurses to assert themselves as clinical leaders.

Nurses’ involvement in clinical governance (De Kok et al., 2023; van Kraaij et al., 2020) and the creation of practice environments conducive to career development (van Dongen & Hafsteinsdóttir, 2022; van Kraaij et al ., 2020) are strategies that promote clinical leadership in nursing, and practice environments can facilitate or hinder the performance of the clinical leader role (Cummings et al., 2021; Isler et al., 2021). Strategies promoting clinical leadership in nursing must, therefore, be comprehensive, in order to integrate the nurse as a member of a team, but also the organization as a macrosystem that has the power to influence practice environments and team development (Isler et al. al., 2021). Its definition should be based on the assumption that qualified and well-trained clinical leaders produce positive results (Mianda & Voce, 2018). These authors emphasize the understanding of leadership as a holistic concept, as empowerment for leadership appears to be more effective when compared to the use of strategies based on the selective understanding of clinical leadership in nursing.

Strengths and limitations of the study

A systematic search strategy was used that allows understanding of the research method, as well as replication of the study. Conducting research in six databases allowed extensive mapping of published scientific evidence and grey literature. The definition of eligibility criteria and the selection of studies through blind reading and analysis of the title and abstract are also strengths of this study. It is important to mention the subjectivity inherent in the interpretative synthesis of the content analysis of the included studies, which can reduce the level of transparency of the study. Some of the included studies investigated the perspective of multidisciplinary teams, which may generate some bias in the interpretation of the results. The behaviors and strategies identified may not be unique to nurses, although they are considered to have significance in nursing practice. Limiting publication languages may result in reduced reach of results.

Conclusion

Clinical leadership must be recognized as a concept with the potential to influence the individual, peers, multidisciplinary team and healthcare organization (International Council of Nurses, 2017). It has a positive impact on health care outcomes, namely by improving the quality and safety of care, increasing job satisfaction and retaining nurses (Ashour et al., 2022).

Clinical nurse leaders are essential for organizational success, so it is imperative to define strategies that promote clinical leadership behaviors. The results of this literature review emphasize that these strategies are related to the nurse, the multidisciplinary team, the organization and entities external to the health organization. It was evident that leadership behaviors are associated with effective communication skills, decision making, clinical experience, support, mentoring, education, and team building. Nursing and leadership training can influence the development of leadership behaviors in nurses in clinical practice by facilitating evidence-based practice, underpinning clinical competence and providing structures that allow responding to organizational demands.

Although the concept of clinical leadership is experiencing growing interest in research, there are still some gaps that need to be explored. The clinical leader's performance depends on a successful transition to the leadership role, so it is suggested that leadership programs and their impact on this transition be evaluated.

Authors' contribution

Conceptualization, O.M.R., J.G., E.J. and B.A.; data curation, O.M.R., J.G. and E. J.; formal analysis, O.M.R., J.G., E.J. and B.A.; investigation, O.M.R., E.J. and B.A.; methodology, O.M.R., E.J. and B.A.; project administration, O.M.R.; resources, O.M.R., E.J. and B.A.; software, O.M.R., J.G. and E. J.; supervision, E.J. and B.A.; validation, O.M.R., J.G., E.J. and B.A.; visualization, O.M.R., J.G., E.J. and B.A.; writing - original draft, O.M.R.; writing - review and editing, O.M.R., J.G., E.J. and B.A.