Introduction

The increase in average life expectancy reflects the progressive ageing of the population and, in turn, the growing prevalence of chronic diseases. As a result, there is a clear need for more healthcare, both in primary healthcare and at the hospital level. The latter is the most marked by overcrowded services and increasing demands on the number of beds available for hospitalisation (Cunha et al., 2017).

Acute and/or chronic patients in need of hospital care who meet the conditions can be cared for at home, as there is an alternative to conventional hospitalisation: home hospitalisation.

The primary model of home hospitalisation, known as Home Care, emerged in the United States in the 1940s, following the Second World War, to deinstitutionalise hospital care and create a beneficial environment for patients on physical, psychological, sociological, and spiritual levels (Delerue & Correia, 2018).

In Portugal, the experience of home hospitalisation is relatively recent, with the creation of the Home Hospitalisation Unit (UHD) at Hospital Garcia de Orta in November 2015, and it was later extended to other hospitals.

According to DGS standard no. As 20 of 2018, home hospitalisation (HD) is a model of care at the hospital level in the home, which replaces conventional hospitalisation but continues to provide clinical care on an ongoing basis (Direção Geral da Saúde [DGS], 2018). This hospitalisation is by the wishes of the patient and their family, but follows a series of clinical, social and geographical criteria. Thus, the clinical situation must be transitory, acute or chronic, with a known diagnosis and clinical stability that allows the patient to remain at home. The home must have good hygiene and sanitary conditions, a safe environment, telephone contact and the presence of a carer. Geographically, the patient's home must be within the area of the hospital unit of reference, considering distance and travel time, to guarantee timely intervention in the event of a worsening clinical situation (Chan, 2022; DGS, 2018).

The clinical situations eligible for HD may include acute or chronic pathology, involving chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, renal failure, cirrhosis of the liver, and other pathologies that can be managed at home. It ensures the degenerative organic process in a terminal situation, which requires intensive and/or specialised palliative care when there is an incurable, advanced and progressive disease (oncological or non-oncological), in conjunction with the Intra-hospital Palliative Care Support team. HD also supports post-operative care and/or treatment of decompensated chronic medical pathology in the post-surgery context (DGS, 2018).

Referred clinical situations are handled by a multidisciplinary team, coordinated by a doctor and a nurse. Home visits are scheduled according to the needs of each patient, and can be singular, interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary (Tosatto et al., 2019).

The nurse provides nursing care according to the identified nursing diagnoses. This health professional is responsible for liaising with in-hospital nurses and the family nurse of the functional health unit where the patient is registered.

As the provision of nursing care has different meanings for each patient, nursing practice can be evaluated by patient satisfaction levels. Satisfaction consists of quality standards, as patients evaluate the quality of the service based on what they desire, expect and observe. It can be defined as an individual assessment of different dimensions (Goh & Vehvilainen-Julkunen, 2016). Evaluating satisfaction with HD nursing care is an essential indicator for guaranteeing the quality of care, humanising care and optimising available resources.

From the literature review we had access to, national and international studies on home hospitalisation are scarce and do not focus on satisfaction with nursing care. However, the available data points to its effectiveness and good acceptance as an alternative to conventional hospitalisation, with a positive impact on various health indicators. Patients and caregivers have demonstrated safety regarding the care provided, and there has also been a reduction in family burden. In addition, this type of care helps to relieve pressure on hospital services and favours the provision of more patient- and family-centred care (Chan, 2022; Cunha et al., 2017; and Farinha-Costa & Reis-Pina, 2024). How satisfied are patients with nursing care in the context of home hospitalisation? The study aimed to describe the level of satisfaction with nursing care among a group of patients undergoing home hospitalisation in a region of northern Portugal.

1. Methods

A quantitative, descriptive-correlational, cross-sectional study was carried out.

1.1 Sample

The study involved 30 patients being hospitalised at home. In December 2023, the northern region of Portugal had 116 beds for HD, giving the sample a representativeness of 26% of the accessible population (SNS, 2023). Data were collected in a public hospital in northern Portugal, using non-probabilistic convenience sampling. Participants were selected with the support of the home hospitalisation nursing team, who identified patients with the cognitive and functional capacity to answer the questionnaire.

1.2 Data collection instrument

A data collection instrument was constructed consisting of three groups: group I - sociodemographic variables (age, gender, marital status and educational qualifications); group II - clinical variables (independence for activities of daily living, pathology that led to hospitalisation, the number of hospitalisations at home, routes of therapeutic administration and types of care provided by the nurse) data obtained by consulting the clinical file of the home hospitalisation team; group III - Citizen Satisfaction with Nursing Care Scale, validated for Portugal.

This scale was validated for the Portuguese population by Rodrigues and Dias (2003), who authorised the use of the scale for the study. The scale has two dimensions: the first consists of 28 items that reflect patient satisfaction according to the experience dimension, and the second consists of 19 items that also reflect patient satisfaction. The first dimension is assessed using a Likert scale with seven possible answers: "completely disagree", "strongly disagree", "somewhat disagree", "neither disagree nor agree", "somewhat agree", "strongly agree" and "completely agree". Thus, each item can correspond to a maximum value of 7, with the lowest value being 1. The sum of all the items can reach a maximum score of 196 points (28 x 7) and a minimum score of 28 points. The second section has five alternative answers: "dissatisfied", "not very satisfied", "quite satisfied", "very satisfied" and "completely satisfied". The first term corresponds to a value of 1 and the last term to a value of 5, so the sum of all the items can reach a minimum score of 19 points and a maximum score of 95 points (19 x 5) (Rodrigues & Dias, 2003). However, item 1.34, which belongs to the dimension of the patient's opinion, refers to satisfaction with the hospital unit, in the sense that the comfort is similar to that of their home. It was therefore not considered in the study, as the participants were hospitalised at home, so the sum of all the items ranges from a minimum score of 18 points to a maximum score of 90 points (18 x 5).

1.3 Data collection procedure

The information was collected in April 2023. The study was carried out in collaboration with the nursing team that was part of the home hospitalisation project. During visits, patients were asked if they were interested in taking part. Those who accepted were given an informed consent form and then asked to complete the questionnaire themselves.

1.4 Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0 was used to analyse the data. The significance level was set at 0.05. In the descriptive analysis of the variables under study, the mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for quantitative variables. Absolute and relative frequencies were used for qualitative variables. Spearman's correlation coefficient test was used to analyse the relationship between the two dimensions of the Nursing Care Satisfaction Scale.

2. Results

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characterisation

Table 1 shows that 30 patients participated in the study, comprising 13 males and 17 females, aged between 42 and 99 years, with an average age of 70.43 ± 16.42 years. In terms of clinical characterisation, the majority of participants (19/63.3%) were independent in carrying out their activities of daily living, and the reason for hospitalisation was primarily due to respiratory pathology (12/40%).

Table 1 Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients in home hospitalisation at a hospital in northern Portugal (n =30)

| Variables | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female Male | 17 13 | 56,7% 43,3% |

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 70,43 ± 16,421 (42 - 99) | Age (Mean ± SD) | |

| Marital status | Single Married Widowed Divorced | 1 20 8 1 | 3,3% 66,7% 26,7% 3,3% |

| Academic qualifications | No schooling Basic Education Secondary education Higher Education Master's Degree | 5 18 4 2 1 | 16,7% 60% 13,3% 6,7% 3,3% |

| Independence to carry out activities of daily living | Yes No | 19 11 | 63.3% 36,7% |

| Clinical speciality that led to hospitalisation | Pulmonology Urology Endocrinology Cardiology Dermatology Orthopaedics Gastroenterology | 12 6 5 3 2 1 1 | 40% 20% 16,7% 10% 6,7% 3,3% 3,3% |

| Hospitalised at home | For the first time For the second time | 26 4 | 86,7% 13,3% |

| How long have you been hospitalised at home? | Up to 2 months 2 to 4 months 4 to 6 months More than 6 months NR | 9 3 3 9 6 | 30% 10% 10% 30% 20% |

Regarding the study sample, 20 (66.7%) of the patients were married. Regarding educational qualifications, 18 (60%) of the patients had attended primary school, and 5 (16.7%) had no formal schooling. Regarding hospitalisation, the majority (26/86.7%) of patients were being hospitalised at home for the first time. In terms of length of stay, there were two main groups, with nine patients in each: those hospitalised for up to 2 months and those hospitalised for more than 6 months.

Satisfaction with Nursing Care

The internal consistency of the Citizen Satisfaction with Nursing Care Scale was assessed. Cronbach's alpha coefficient for all 46 items in the scale was 0.979. The alpha for the 28 items in the experience dimension was 0.946, and the alpha for the 18 items in the opinion dimension was 0.988. These values, so close to one, indicate that the scale is reliable for measuring patient satisfaction with nursing care from their perspective.

Varying the response options from 1 to 7 (in the experience dimension) and from 1 to 5 (in the opinion dimension), the neutral point of the scale is at 4 and 3, respectively. Therefore, all the items where the average of the 30 answers exceeded these values were considered "positive". Each patient's level of satisfaction with nursing care was expressed by the average of all the answers to the items on the scale, ranging from a minimum of '1' to a maximum of '7' points, and a minimum of '1' to a maximum of '5', respectively.

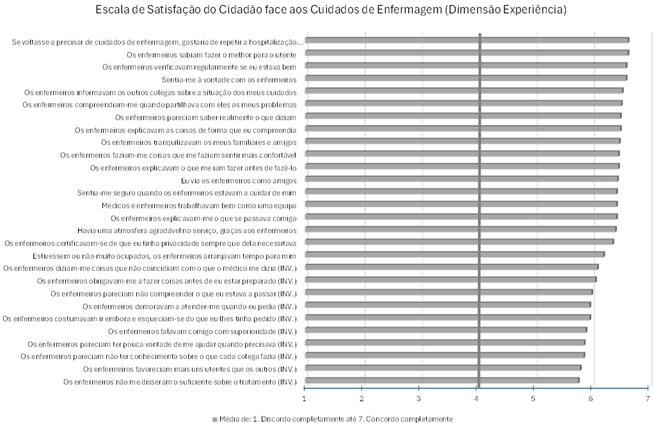

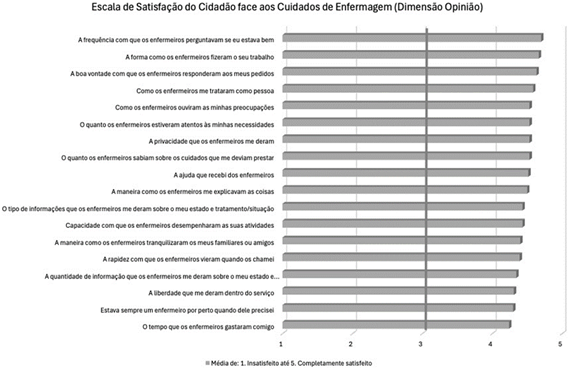

The participants expressed a positive opinion, as shown in Figures 1 and 2. All the items on the scale exceeded '4' and '3' respectively. It should be noted that in graph 1, where all the items were formulated in the negative (e.g. "Nurses favoured some users more than others"), the answers were inverted before being included in the graph. Therefore, when the suffix (INV.) appears on the YY axis, the interpretation should be the inverse of the question being asked (e.g. "Nurses favoured some patients more than others (INV.)" should be read as "Nurses did not favour some patients more than others").

Figure 1 Average response of the 30 patients to the items on the Citizen Satisfaction with Nursing Care Scale, in the dimension of experience

Figure 2 Average response of the 30 patients to the items on the Citizen Satisfaction with Nursing Care Scale, in the opinion dimension

By varying the response options from 1 to 7 (both on the overall scale and the experience dimension) and from 1 to 5 (on the opinion dimension), the original mean values and standard deviation were converted to a weighted scale of 0 to 100 per cent. In this way, it is now possible to compare the three scores on the same percentage scale. So, analysing patient satisfaction by dimension, we see in Table 2 that the average score for the 30 patients was 6.2 points ± 0.93 (or 86.7% ± 15.5% on the weighted scale). These high values confirm that the patients had good levels of satisfaction. The opinion dimension had average values similar to those of the experience dimension, as 85.5% is very close to 87.2%. However, it can be said that the experience dimension contributed slightly more to patients' overall satisfaction than the opinion dimension.

Table 2 Average levels of satisfaction with home hospitalisation (including by dimension), of patients in home hospitalisation (n=30)

| Average simple/weighted | Standard deviation simple/weighted | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall score (1 to 7) | 6,20 / 86,7% | 0,93 / 15,5% |

| Experience" dimension (28 items) (1 to 7) | 6,23 / 87,2% | 0,89 / 14,8% |

| Opinion" dimension (18 items) (1 to 5) | 4,42 / 85,5% | 0,81 / 20,2% |

Table 3 shows that none of the categorical variables had a statistically significant influence on satisfaction with nursing care. Despite this, men were slightly more satisfied than women, especially in the opinion dimension (4.58 vs. 4.30; p-value = 0.174). Patients who were independent in their ADLs were also slightly more satisfied than those who were dependent (6.41 vs. 5.84 in the overall satisfaction score; p-value = 0.136).

Only the age variable had a significant influence on satisfaction with nursing care. It was found that the older patients who were hospitalised at home had a lower level of satisfaction with the nursing care provided.

The correlation levels are weak (between -0.3 and -0.5), but statistically significant in the experience dimension (p-value = 0.012) and the overall perspective of the scale (p-value = 0.011).

Table 3 Variables influencing patients' levels of satisfaction with nursing care during home hospitalisation (n=30)

| Factor | Level of Opinion Satisfaction (Mean ± SD) | p-value | Level of satisfaction with the experience (Mean ± SD) | p-value | Overall Satisfaction Level (Mean ± SD) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female Male | 4,30 ± 0,84 4,58 ± 0,78 | 0,174 | 6,22 ± 0,84 6,25 ± 0,98 | 0,541 | 6,14 ± 0,94 6,29 ± 0,94 | 0,515 |

| Marital status | Married Not married | 4,45 ± 0,75 4,36 ± 0,98 | 0,982 | 6,41 ± 0,72 5,88 ± 1,12 | 0,199 | 6,34 ± 0,80 5,93 ± 1,15 | 0,233 |

| Educational qualifications | No schooling Basic Education More than basic education | 4,21 ± 1,25 4,48 ± 0,77 4,40 ± 0,64 | 0,605 | 5,42 ± 1,38 6,45 ± 0,76 6,24 ± 0,50 | 0,080 | 5,54 ± 1,42 6,39 ± 0,86 6,20 ± 0,53 | 0,140 |

| Independence to carry out activities of daily living | Yes No | 4,62 ± 0,67 4,07 ± 0,95 | 0,121 | 6,40 ± 0,77 5,94 ± 1,04 | 0,216 | 6,41 ± 0,80 5,84 ± 1,06 | 0,136 |

| Number of times hospitalised at home. | First Monday | 4,38 ± 0,86 4,68 ± 0,37 | 0,853 | 6,20 ± 0,92 6,44 ± 0,75 | 0,689 | 6,16 ± 0,97 6,46 ± 0,69 | 0,668 |

| Age | -0,336 | 0,069 | -0,453 | 0,012 | -0,456 | 0,011 | |

3. Discussion

The study involved 30 patients who were hospitalised at home, the majority of whom were female, with an average age of 70.43 years (± 16.42), predominantly married and with primary school education. These data reflect the typical profile of users of this type of health service and are consistent with other studies conducted in similar contexts (Almeida, 2021; Cunha et al., 2017; Delerue et al., 2018; Henriques & Portela, 2023). Also noteworthy was the prevalence of respiratory pathologies as the main reason for hospitalisation, which is consistent with the growing importance of respiratory diseases in home-based clinical settings (Almeida, 2021; Meireles et al., 2024; Nikmanesh et al., 2024).

Home hospitalisation has been identified as an effective alternative in the Portuguese context, particularly in the provision of palliative care, as it reduces hospital readmissions and increases patient and carer satisfaction (Farinha-Costa & Reis-Pina, 2025). In this study, the high levels of satisfaction with nursing care are noteworthy. The overall average score was 6.20 (± 0.93), indicating a positive perception of the care provided. The "experience" and "opinion" dimensions also showed high results, with averages of 6.23 (± 0.89) and 4.42 (± 0.81), respectively. These results reflect the appreciation of aspects such as the provision of individualised care, privacy and the clarity of the explanations given by the nursing team, in line with the DGS recommendations for the humanisation of healthcare (DGS, 2018).

Although variables such as gender, marital status and functional independence showed no statistically significant influence on satisfaction levels, some interesting trends were observed. For example, male patients reported slightly higher levels of satisfaction in the opinion dimension (4.58 vs. 4.30), while patients who were independent for ADLs showed a tendency towards greater overall satisfaction (6.41 vs. 5.84). These results, although not statistically significant, suggest subtle differences in perceptions of satisfaction that could be explored in future studies with larger sample sizes.

Age, on the other hand, showed a statistically significant influence on satisfaction with the care received, especially in the "experience" dimension (ρ = -0.453; p = 0.012) and in global perception (ρ = -0.456; p = 0.011). These results suggest that older patients tend to report lower levels of satisfaction, possibly due to specific expectations or needs that may not be fully met. Previous studies indicate that home hospitalisation can provide a safe and satisfying environment for patients and their carers, contributing to a lower rate of hospital readmissions and an increased perception of comfort and dignity (Henriques, 2023).

Another relevant point is the importance of ensuring clear and effective communication, especially for older populations, who may face additional barriers related to understanding information about the care provided. This includes using accessible language, clarifying doubts, and reinforcing health education -elements that can significantly improve the patient experience and, consequently, satisfaction levels, particularly with nursing care (Goh & Vehvilainen-Julkunen, 2016).

When interpreting the results, it is essential to consider some limitations that may influence the generalisability and robustness of the conclusions. Firstly, the small sample, composed for convenience, represents a significant limitation, as it does not reflect the diversity of a broader population, which compromises the ability to generalise the results to other contexts or groups. Furthermore, collecting data at a single point in time without conducting a longitudinal analysis prevents the observation of possible variations or trends over time, thereby limiting the dynamic understanding of the phenomenon under study.

Another relevant point is the heterogeneity observed in the participants' clinical conditions and the duration of home hospitalisation, which may act as confounding variables. These individual differences were not fully explored, which suggests that factors other than those specifically analysed may have influenced the results. The lack of control or inadequate control of these confounding variables may have led to interpretations that do not reflect the proper relationship between the variables of interest.

Therefore, for a more in-depth and accurate understanding of the phenomenon in question, future studies should include larger and more representative samples, preferably with a multicenter approach, which will allow for a greater diversity of contexts and a more accurate assessment of the variables involved. Furthermore, the implementation of a longitudinal design will be crucial in order to observe the effects over time and determine whether the results found are sustained or evolve over months or years. These methodological strategies will significantly contribute to confirming the conclusions of this study and to expanding knowledge on the subject by providing more robust and generalisable data.

Implications for Nursing Practice

The results of the study underline the importance of a patient-centred approach, which values not only the provision of high-quality clinical care, but also the promotion of a positive experience for the patient and their family. This includes guaranteeing privacy, paying attention to individual preferences and adapting care to each person's specific needs. Also emphasised is the need to develop specific strategies to meet the expectations of older patients, with a focus on communication and health education, as well as meeting patients' preferences for being cared for at home.

Conclusion

This study provides significant evidence of the high levels of satisfaction among HD patients, highlighting the quality and effectiveness of the nursing care provided. However, it also emphasises the importance of specific strategies to improve the experience of vulnerable groups, such as older patients. More comprehensive future studies with greater statistical power are needed to validate and expand on these findings, contributing to the advancement of knowledge in the field and the continuous improvement of nursing practice in home care settings.

Authors' contribution

Conceptualization, I.A., C.S. and F.P.; data curation, I.A. and R.J.; formal analysis, I.A., L.S., C.S. and F.P.; investigation, I.A., L.S., C.S. and F.P.; methodology, L.S. and I.A.; project administration, I.A.; software, R.J.; writing-original draft, I.A., L.S., C.S. and F.P.; writing-review and editing, I.A., L.S., C.S. and F.P.