Introduction

While national curricula were previously shaped by modern theories, today a skill-oriented structure is growing in importance due to rapid changes in information dynamics, technological advancements, and digitalization. Despite being in the early stages of the 21st-century digital age, skills such as versatility, analytical thinking, problem-solving, productivity, responsibility, flexibility, autonomy, communication, collaboration, creativity, and digital literacy have become essential for individuals to compete globally and adapt to change (Partnership for 21st Century Skills [P21], 2019). These competencies, aligned with the dynamics of the age, prioritize thinking skills within national educational objectives. One of these priorities is computational thinking (CT) skills, which focus on knowledge production through computer-oriented thinking (Sneider et al., 2014; Wing, 2006, 2008). CT is increasingly recognized as a valuable competence area in contemporary education (Boom et al., 2022; Looi et al., 2024). This phenomenon can be attributed to computers' ability to restructure daily life problems in ways that enhance solution processes (International Society for Technology in Education [ISTE] & Computer Science Teachers Association [CSTA], 2011). While CT skills comprise various components, the core principle is that personal computers have the potential to transform individual lives and enhance thinking and learning processes (Papert, 1980). Thus, understanding and applying the principles of computer science, along with effectively utilizing problem-solving processes, significantly increases the demand for CT skills.

In recent years, CT skills have become increasingly important, particularly within teacher education (ISTE & CSTA, 2011). Equipping preservice mathematics teachers (PMTs) with CT skills is critical for developing their algorithmic thinking and analytical abilities within problem-solving processes (Looi et al., 2024; Wing, 2006). While it is recommended that CT skills be introduced early in education, research on effective methods for imparting these skills, specifically in preparing preservice teachers for this process, remains limited (Avşar, 2023; Grover & Pea, 2013; Israel & Lash, 2020; Kafai et al., 2019; Kaya, 2024; Lockwood & Mooney, 2018; Özyurt & Aslan, 2023; Shute et al., 2017; Yadav et al., 2017). This highlights a gap in the field, particularly regarding the identification and implementation of methods to effectively enhance the CT skills of PMTs (Lye & Koh, 2014; Navarro & de Sousa, 2023; Wing, 2008). Providing CT skills training to PMTs plays a key role in enabling students to develop creative solutions to complex problems and in fostering deeper learning (Ching & Hsu, 2024; Grover & Pea, 2013). Thus, the design-based learning (DBL) approach can significantly contribute to the development of CT.

This situation reveals that there is a gap in the field, especially in terms of determining and implementing methods that will effectively improve the CT skills of PMTs (Lye & Koh, 2014; Navarro & de Sousa, 2023; Wing, 2008). Equipping PMTs with CT skills plays a critical role in enabling students to develop creative solutions to complex problems and deepening their learning processes (Grover & Pea, 2013). Therefore, preservice teachers' acquisition of CT skills brings with it the need for a pedagogical approach beyond traditional methods. The acquisition of CT skills by preservice teachers necessitates a pedagogical approach that transcends traditional methods.

This study investigates effect of the DBL approach on the acquisition of CT and self-efficacy perception towards teaching computational thinking (SEPTCT) skills among PMTs and seeks to fill a critical gap in the field. DBL stands out as a powerful method that supports PMTs’ creative thinking, problem-solving and algorithmic approach development skills through a structured design process (Harel & Papert, 1991). Given these attributes, DBL is expected to make significant contributions to the acquisition of CT skills among PMTs. In contrast to previous research, this study seeks to facilitate a deeper acquisition of CT skills among preservice teachers through the structured learning environment provided by the DBL approach. The DBL approach encourages preservice teachers to engage in active learning and problem-solving activities, while fostering a hands-on, experiential learning environment beyond traditional teaching methods. Aligned with these objectives, the following research questions (RQs) were designed and answers were sought:

RQ 1. Does a significant difference exist between the pre-test and post-test scores for CT and SEPTCT among PMTs in the experimental and control groups?

RQ 2. What effect does the DBL approach have on the CT skills of PMTs?

RQ 3. What effect does the DBL approach have on the SEPTCT of PMTs?

RQ 4. What are the opinions of the PMTs in the experimental group regarding the DBL approach?

Computational Thinking (CT) and Design Based Learning (DBL)

As a crucial component of modern education, CT lays a strong foundation for developing students' problem-solving, analytical and algorithmic thinking skills. Imparting these skills through the teaching process plays a critical role in enabling individuals to devise innovative and systematic solutions to complex problems. To ensure the success of this process, educators must possess in-depth knowledge of CT pedagogy and competence in implementing effective teaching approaches. However, there is limited research on structured approaches for developing CT skills in preservice teachers (Brennan & Resnick, 2012). To accommodate the increasingly computational nature of mathematics, Weintrop et al. (2016) developed a taxonomy organized into four main categories: data handling, modeling and simulation, computational problem-solving, and systems thinking. Research indicates that when CT is taught through these four components, students deepen not only their technical skills but also their conceptual understanding. This structured CT framework offers a clear path for teachers to integrate CT into their lesson plans. Shute et al. (2017) highlight the value of approaches such as game and project-based learning for effective CT introduction in education and emphasize the necessity of process-based evaluation methods. Research demonstrates that CT has a strong relationship with both cognitive and emotional components, such as self-efficacy and motivation. Yadav et al. (2017) highlight CT’s role as an interdisciplinary skill in teacher education and recommend project-based learning approaches that incorporate hands-on activities and collaboration to enable preservice teachers to acquire CT skills. Israel and Lash (2020) claim that integrating mathematics with CT strengthens students' systematic problem-solving skills and fosters a deeper understanding of mathematical concepts.

Studies indicate that CT applications deepen mathematical domain knowledge and promote the interaction between computer science and mathematical concepts (Looi et al., 2024; Pei et al., 2018; Ye et al., 2023). Although CT research has been applied across various educational levels, it has been primarily adopted at the K-12 level (Grover & Pea, 2013; Kafai et al., 2019). CT-based approaches to mathematics teaching have become widespread in the K-12 context, fostering DBL research and establishing the concept of "computationally enhanced mathematics education" (Ng & Cui, 2021, p. 848). These studies have enhanced mathematics learning and promoted the integration of CT into engineering, technology, and science education by providing opportunities for real-world and interdisciplinary connections (Ching & Hsu, 2024; Ng & Cui, 2021; Pei et al., 2018; Ye et al., 2023).

Following Wing's (2006) introduction of the concept of CT, CT has become increasingly recognized as a fundamental 21st-century skill. Extending beyond digital literacy, CT provides a comprehensive skill set that enhances individuals' abilities to solve complex problems, think algorithmically, and analyze systematically (Brennan & Resnick, 2012; Kafai et al., 2019; P21, 2019; Pei et al., 2018; Ye et al., 2023). With technological advances, CT skills are regarded as an essential competency in fields ranging from education to industry, enabling individuals to develop innovative solutions within these areas. CT serves as a cornerstone in reshaping educational approaches by adding a new dimension to the processes of teaching and learning mathematics (Looi et al., 2024; Weintrop et al., 2016). This skill equips students with problem-solving and analytical thinking skills, facilitating deeper understanding and engagement in mathematics education. CT's integration into mathematics education is rooted in Papert's (1980) vision of developing children's CT skills with the Logo programming language. Papert believed that powerful computational technologies and algorithmic thinking could transform students' learning and argued that CT could play a pivotal role in enhancing problem-solving skills. Weintrop et al. (2016) developed a comprehensive taxonomy to align CT with the increasingly computational nature of contemporary science and mathematics. This classification aims to make CT applicable not only in computer science but also in other disciplines, including mathematics, engineering, and science, facilitating the integration of computational skills across various fields.

The strong relationship between mathematics and CT emphasizes CT's potential for enhancing mathematical skills. The National Research Council [NRC] (2010) report demonstrates that CT aligns with mathematical thinking processes by incorporating key components such as hypothesis generation, data management, abstraction, and debugging. These components provide valuable tools for enhancing mathematical thinking when analyzing complex problems. CT supports the fundamental dynamics of mathematics with skills including algorithmic and algebraic thinking, modeling, and abstraction (Shute et al., 2017). Gadanidis et al. (2017) state that CT establishes a natural connection with mathematics by enabling the discovery of logical structures and modeling abilities. In this context, CT constitutes the epistemological basis of mathematics, enables multidimensional thinking and deepens problem-solving processes (Weintrop et al., 2016; Wing, 2008).

DBL is widely regarded as an effective approach in mathematics education for developing students' problem-solving and analytical thinking skills (Barab & Squire, 2004). This method seeks to ensure that students not only learn abstract mathematical concepts but also develop knowledge and skills applicable to real-world contexts (Kolodner et al., 2003). DBL fosters a more meaningful and interactive learning experience by involving students actively in the problem-solving process, which in turn increases student motivation and learning retention (Gresalfi et al., 2009). DBL is a teaching method that, in the classroom environment, aims to equip students with essential problem-solving skills, such as imagination, creativity, problem visualization, and holistic thinking (Mehalik & Schunn, 2006). With this approach, students have the opportunity to deeply engage in the learning process by learning from their mistakes as they develop their own solutions (Hmelo-Silver, 2004). Unlike traditional instruction, DBL engages students in authentic problem-solving, guiding them to generate, test, and revise solutions. This approach encourages deep cognitive engagement and facilitates pedagogical planning by aligning instruction with students’ evolving conceptual understanding and reflective feedback (Kolodner et al., 2003; Mehalik & Schunn, 2006).

2. Methods

2.1 Research Design

This study adopted a mixed design to assess the effect of a DBL course plan on the CT skills of PMTs. For this purpose, an intervention design, a sophisticated form of mixed-methods approach, was chosen. The purpose of this design is to address a research problem by incorporating qualitative data into the research process through an experiment or intervention trial program (Cresswell, 2014). Consequently, a quasi-experimental study procedure was developed, integrating qualitative data within an experimental intervention design that included a pre and post-test model. The symbolic representation of the design, measured both before and after the experiment, is presented in Table 1.

2.2 Participants, Sampling Technique, and Sample Size

The study participants were selected to enable an in-depth examination of both quantitative and qualitative data within the framework of the mixed-method research model. The participant group comprised 40 PMTs enrolled at a state university. The group consisted of 70% females (n=28) and 30% males (n=12). Purposeful maximum diversity sampling was used to determine the study group. The key criteria for inclusion were: (i) age range (20-23), (ii) previous experience with coding or CT activities, (iii) self-reported digital literacy level, and (iv) being enrolled in a mathematics education course taught by one of the researchers. This selection process ensured both instructional relevance and ecological validity within the existing teacher education context. Based on the study criteria, participants were divided equally, with 20 assigned to the experimental group and 20 to the control group.

2.3 Data collection tools and process

The data collection tools consist of the Computational Thinking (CT) (Korkmaz et al., 2017) and Self-Efficacy Perception towards Teaching Computational Thinking (SEPTCT) (Özçınar & Öztürk, 2018) scales, along with a semi-structured interview form. The CT scale consists of 29 items and five sub-factors. The sub-factors are creativity, algorithmic thinking, cooperativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. Items on the scale are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from "never" to "always." Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) confirmed the scale’s construct validity, indicating that the five-factor structure aligned with the data set [CMIN/DF=3.23; RMSEA=0.062; GFI=0.91; AGFI=0.90; CFI=0.95; IFI=0.97; SRMR=0.044]. The total Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient for the scale was calculated as 0.80 in this study. The SEPTCT scale comprises 31 items and four sub-factors. The sub-factors are problem construction, algorithmic thinking, teaching assessment, and planning and teaching. CFA confirmed the scale’s construct validity, indicating that the four-factor structure aligned with the data set [CMIN/DF=4.07; RMSEA=0.13; GFI=0.63; CFI=0.97; NNFI=0.97; SRMR=0.04]. The total Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient for the scale was calculated as 0.82 within this study. Researchers developed a semi-structured interview form to evaluate the effectiveness of the design-based education program for PMTs. This form includes questions exploring PMTs knowledge, practices, and perceptions regarding coding and CT. Two experts were consulted for language and content validity, and revisions were made accordingly. A sample question is: “What do you think are the contributions of CT and coding education?” The design-based processes in the study involve assessing participants' current knowledge and skills, expectations from the training program, modules, courses, practice activities, digital, written, and visual materials used in the training, a pilot application with a small group, planned scope and content for the target audience, and the program’s overall effectiveness (see Figure 1).

The design-based teaching approach includes four modules and 24 sessions (see Table 2). Based on reflective and social cluster formation, the educational theoretical framework incorporates Shulman and Shulman's (2009) model of "fostering a community of learners", Schön's (1983) concept of "reflective practitioners", and Vygotsky's (1934/1986) social development theory. The activities presented in Table 2 incorporate CT-rich educational content, including group sharing, collaborative learning, brainstorming, conversation circles, synectics, focus group interviews, and tutorial discussions. Individual studies showcase original designs developed from participants' group experiences.

Table 2 Integrated course plan designed for PSMT

| Module | Week | Session | Duration | Course Activity | Educational Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Module 1 Coding Training | 1st Week | 1 | 10 min | CCD | Definition of coding |

| 2 | 10 min | CCD | Concepts related to coding | ||

| 3 | 10 min | RCD | The importance and necessity of coding education | ||

| 4 | 10 min | RCD | Reasons for coding skills in terms of 21st-century skills | ||

| 5 | 20 min | RID | The nature of coding skills | ||

| 6 | 30 min | RCD | Basic information about the coding process | ||

| Module 2 Computational Thinking Training | 2nd Week | 7 | 10 min | CCD | Definition of CT |

| 8 | 10 min | CCD | CT education and its importance | ||

| 9 | 10 min | RCD | Problem-solving in the context of CT | ||

| 10 | 20 min | RCD | Components of CT | ||

| 11 | 20 min | RID | Dimensions of CT | ||

| 12 | 20 min | RID | CT processes | ||

| Module 3 Teaching Coding and Computational Thinking | 3rd-4th Weeks | 13 | 20 min | CCD | CT in light of instructional approaches |

| 14 | 20 min | CCD | Developmentally appropriate applications | ||

| 15 | 20 min | RCD | Coding and CT in the context of constructivism | ||

| 16 | 30 min | RCD | Positive technological development | ||

| 17 | 45 min | RID | Activities unplugged-1 | ||

| 18 | 45 min | RID | Activities unplugged-2 | ||

| Module 4 Developing Activities for Computational Thinking | 5th-6th-7th-8th Weeks | 19 | 45 min | CCD | Algorithm design (signs, constants, variables, loops etc.) |

| 20 | 45 min | CCD | Separation (character, graphic, scenario, etc.) | ||

| 21 | 45 min | RID | Abstraction (code blocks, subjective designs) | ||

| 22 | 45 min | RID | Pattern recognition (sequential operations, loops) | ||

| 23 | 45 min | RID | Data processing (expressions, predicates), debugging | ||

| 24 | 45 min | RID | Modeling (modularity) (real object, image and event) |

Note: CCD: Communal Cluster Discourses RCD: Reflective Cluster Discourses RID: Reflective Individual Discourses

2.4 Data analysis

A normality analysis was first conducted for the quantitative data analysis. Given the sample size, Shapiro-Wilk test results were examined, confirming a normal data distribution (p>0.05). In addition, the skewness and kurtosis values of the measurement tools were examined. The skewness and kurtosis values of the CT scale and its sub-factors ranged from -0.078 to 0.298, while those of the SEPTCT scale and its sub-factors ranged from 0.050 to -0.300. Values within the ±1.50 range for skewness and kurtosis indicate that the data are normally distributed (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). The homogeneity of variances was assessed using Levene's test, and the homogeneity of the variance-covariance matrix was examined with Box’s M test. Furthermore, independent samples t-test, multifactor analysis of variance (MANOVA) for repeated measures, and descriptive statistics were used in evaluating the quantitative data. Content analysis was used to analyze the qualitative data. Descriptive statistics and t-test results based on the preliminary measurements of students in the experimental and control groups are presented in Table 3. According to the table, there is no significant difference between the pre-test total score averages of preservice teachers in the experimental and control groups for both the CT (t(38)=0.210, p>0.05) and the SEPTCT (t(38)=-0.242, p>0.05) scales. Additionally, no significant difference was found in the pre-test average scores across the scales' sub-dimensions (p>0.05).

Table 3 T-test results for the pre-test scores of the experimental and control groups

| Scales | Dimension | Groups | N | X | SD | MD | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Thinking | Creativity | Experiment | 20 | 3.71 | 0.51 | -0.037 | 38 | -0.264 | 0.793 |

| Control | 20 | 3.75 | 0.37 | ||||||

| Algorithmic thinking | Experiment | 20 | 3.57 | 0.51 | 0.125 | 38 | 0.730 | 0.470 | |

| Control | 20 | 3.45 | 0.56 | ||||||

| Cooperativity | Experiment | 20 | 3.88 | 0.78 | 0.050 | 38 | 0.232 | 0.818 | |

| Control | 20 | 3.83 | 0.55 | ||||||

| Critical thinking | Experiment | 20 | 3.59 | 0.80 | 0.040 | 38 | 0.179 | 0.859 | |

| Control | 20 | 3.55 | 0.60 | ||||||

| Problem-solving | Experiment | 20 | 3.88 | 0.37 | -0.041 | 38 | -0.389 | 0.700 | |

| Control | 20 | 3.92 | 0.29 | ||||||

| Grand Total | CT Skills (Total) | Experiment | 20 | 3.72 | 0.37 | 0.020 | 38 | 0.210 | 0.834 |

| Control | 20 | 3.70 | 0.22 | ||||||

| Self-Efficacy Perception towards Teaching Computational Thinking | Teaching algorithmic thinking | Experiment | 20 | 3.83 | 0.47 | -0.025 | 38 | -0.185 | 0.854 |

| Control | 20 | 3.85 | 0.37 | ||||||

| Teaching evaluation | Experiment | 20 | 3.70 | 0.62 | 0.050 | 38 | 0.283 | 0.779 | |

| Control | 20 | 3.65 | 0.48 | ||||||

| Course planning and teaching methods | Experiment | 20 | 3.65 | 0.52 | 0.035 | 38 | 0.262 | 0.795 | |

| Control | 20 | 3.61 | 0.30 | ||||||

| Teaching problem-posing | Experiment | 20 | 3.89 | 0.28 | -0.060 | 38 | -0.564 | 0.576 | |

| Control | 20 | 3.95 | 0.37 | ||||||

| Grand Total | SEPTCT (Total) | Experiment | 20 | 3.80 | 0.31 | -0.020 | 38 | -0.242 | 0.810 |

| Control | 20 | 3.82 | 0.22 |

Note. SD: Standard Deviation; MD: Mean Difference; df: Degrees of Freedom

2.5 Ethical consideration

The participants were informed about the study’s purpose, the topics to be measured, and the benefits provided. Participation was voluntary, and they were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time or request detailed information. Additionally, they were told that some questions might be uncomfortable and that no monetary compensation would be provided for participation. This research was carried out with the permission of Nevşehir Hacı Bektaş Veli University Publication Ethics Board with the decision numbered 2023.11.265 dated 27.09.2023.

3. Results

Following (Table 4), we present the results of the post-test applied to the group and the discussion and conclusions of this research.

Table 4 T-test results for the post-test scores of the experimental and control groups

| Scales | Dimension | Groups | N | X | SD | MD | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Thinking | Creativity | Experiment | 20 | 4.20 | 0.38 | 0.331 | 38 | 2.916 | 0.006** |

| Control | 20 | 3.86 | 0.32 | ||||||

| Algorithmic thinking | Experiment | 20 | 3.96 | 0.39 | 0.333 | 38 | 2.591 | 0.013* | |

| Control | 20 | 3.63 | 0.42 | ||||||

| Cooperativity | Experiment | 20 | 4.31 | 0.50 | 0.375 | 38 | 2.360 | 0.024* | |

| Control | 20 | 3.93 | 0.49 | ||||||

| Critical thinking | Experiment | 20 | 4.03 | 0.39 | 0.270 | 38 | 2.109 | 0.042* | |

| Control | 20 | 3.76 | 0.41 | ||||||

| Problem-solving | Experiment | 20 | 4.40 | 0.41 | 0.350 | 38 | 3.206 | 0.003** | |

| Control | 20 | 4.05 | 0.25 | ||||||

| Grand Total | CT Skills (Total) | Experiment | 20 | 4.17 | 0.16 | 0.331 | 38 | 5.871 | 0.000*** |

| Control | 20 | 3.84 | 0.18 | ||||||

| Self-Efficacy Perception towards Teaching Computational Thinking | Teaching algorithmic thinking | Experiment | 20 | 4.32 | 0.47 | 0.275 | 38 | 2.134 | 0.039* |

| Control | 20 | 4.05 | 0.32 | ||||||

| Teaching evaluation | Experiment | 20 | 4.31 | 0.50 | 0.500 | 38 | 3.778 | 0.001** | |

| Control | 20 | 3.81 | 0.31 | ||||||

| Course planning and teaching methods | Experiment | 20 | 4.07 | 0.50 | 0.307 | 38 | 2.330 | 0.025* | |

| Control | 20 | 3.76 | 0.31 | ||||||

| Teaching problem-posing | Experiment | 20 | 4.22 | 0.29 | 0.246 | 38 | 2.377 | 0.023* | |

| Control | 20 | 3.97 | 0.35 | ||||||

| Grand Total | SEPTCT (Total) | Experiment | 20 | 4.21 | 0.23 | 0.290 | 38 | 4.519 | 0.000*** |

| Control | 20 | 3.92 | 0.16 |

An examination of Table 4 reveals a significant difference in the CT post-test scores between preservice teachers in the experimental and control groups (t(38)=5.871, p<0.001). Examining the CT scale’s sub-factors, significant differences emerged in the post-test scores for creativity (t(38)=2.916, p<0.01), algorithmic thinking (t(38)=2.591, p<0.05), cooperativity (t(38)=2.360, p<0.05), critical thinking (t(38)=2.109, p<0.05), and problem-solving (t(38)=3.206, p<0.01). A significant difference was found between the experimental and control group scores on the SEPTCT scale in the post-test (t(38)=4.519, p<0.001). In the SEPTCT scale’s sub-factors, significant differences were observed in the post-test scores for the dimensions of teaching algorithmic thinking (t(38)=2.134, p<0.05), teaching evaluation (t(38)=3.778, p<0.01), course planning and teaching methods (t(38)=2.330, p<0.05), and teaching problem-posing (t(38)=2.377, p<0.05).

Table 5 Results of multivariate analysis of variance on mean scores of CT

| Effect | Test | Value | F | Hypothesis df | Error df | p | ƞ_p^2 | Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Pillai's Trace | 0.998 | 4009.48 | 5.00 | 34.00 | 0.000*** | 0.998 | 1.000 |

| Wilks' Lambda | 0.002 | 4009.48 | 5.00 | 34.00 | 0.000*** | 0.998 | 1.000 | |

| Hotelling's Trace | 589.63 | 4009.48 | 5.00 | 34.00 | 0.000*** | 0.998 | 1.000 | |

| Roy's Largest Root | 589.63 | 4009.48 | 5.00 | 34.00 | 0.000*** | 0.998 | 1.000 | |

| Group | Pillai's Trace | 0.505 | 6.938 | 5.00 | 34.00 | 0.000*** | 0.505 | 0.995 |

| Wilks' Lambda | 0.495 | 6.938 | 5.00 | 34.00 | 0.000*** | 0.505 | 0.995 | |

| Hotelling's Trace | 1.020 | 6.938 | 5.00 | 34.00 | 0.000*** | 0.505 | 0.995 | |

| Roy's Largest Root | 1.020 | 6.938 | 5.00 | 34.00 | 0.000*** | 0.505 | 0.995 |

The MANOVA analysis in Table 5 indicates a statistically significant difference in CT score averages between the experimental and control groups of preservice teachers. A statistically significant difference was found at both within-group (F(5-34)=4009.48, p<0.001, λ=0.002, ƞp 2=0.998) and between-group levels (F(5-34)=6.938, p<0.001, λ=0.495, ƞp 2=0.505). These differences indicate a high level of effect.

Table 6 CT impact test results

| Source | Dependent variable | Sum of squares | df | F | p | ƞ_p^2 | Observed power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Thinking | Creativity | 1.097 | 1 | 8.505 | 0.006** | 0.183 | 0.811 |

| Algorithmic thinking | 1.111 | 1 | 6.714 | 0.013* | 0.150 | 0.714 | |

| Cooperativity | 1.406 | 1 | 5.570 | 0.024* | 0.128 | 0.633 | |

| Critical thinking | 0.729 | 1 | 4.447 | 0.042* | 0.105 | 0.538 | |

| Problem-solving | 1.225 | 1 | 10.281 | 0.003** | 0.213 | 0.878 |

The dependent variables in Table 6 reveal statistically significant differences across all CT sub-dimensions between preservice teachers in the experimental and control groups. Specifically, the dimensions of creativity (F(1-38)=8.505, p<0.01, ƞp 2=0.183), algorithmic thinking (F(1-38)=6.714, p<0.05, ƞp 2=0.150), cooperativity (F(1-38)=5.570, p<0.05, ƞp 2=0.128), critical thinking (F(1-38)=4.447, p<0.05, ƞp 2=0.105), and problem-solving (F(1-38)=10.281, p<0.01, ƞp 2=0.213) all demonstrate statistically significant differences. These differences indicate high to medium effect sizes.

Table 7 Results of multivariate analysis of variance on mean scores of SEPTCT

| Effect | Test | Value | F | Hypothesis df | Error df | p | ƞ_p^2 | Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Pillai's Trace | 0.998 | 4002.86 | 4.00 | 35.00 | 0.000*** | 0.998 | 1.000 |

| Wilks' Lambda | 0.002 | 4002.86 | 4.00 | 35.00 | 0.000*** | 0.998 | 1.000 | |

| Hotelling's Trace | 457.47 | 4002.86 | 4.00 | 35.00 | 0.000*** | 0.998 | 1.000 | |

| Roy's Largest Root | 457.47 | 4002.86 | 4.00 | 35.00 | 0.000*** | 0.998 | 1.000 | |

| Group | Pillai's Trace | 0.439 | 6.844 | 4.00 | 35.00 | 0.000*** | 0.439 | 0.986 |

| Wilks' Lambda | 0.561 | 6.844 | 4.00 | 35.00 | 0.000*** | 0.439 | 0.986 | |

| Hotelling's Trace | 0.782 | 6.844 | 4.00 | 35.00 | 0.000*** | 0.439 | 0.986 | |

| Roy's Largest Root | 0.782 | 6.844 | 4.00 | 35.00 | 0.000*** | 0.439 | 0.986 |

The MANOVA analysis in Table 7 indicates a statistically significant difference in SEPTCT score averages between the experimental and control groups of preservice teachers. A statistically significant difference was found at both within-group (F(4-35)=4002.86, p<0.001, λ=0.002, ƞp 2=0.998) and between-group levels (F(4-35)=6.844, p<0.001, λ=0.561, ƞp 2=0.439). These differences indicate a high level of effect.

Table 8 SEPTCT impact test results

| Source | Dependent variable | Sum of squares | df | F | p | ƞ_p^2 | Observed power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Efficacy Perception towards Teaching Computational Thinking | Teaching algorithmic thinking | 0.756 | 1 | 4.554 | 0.039* | 0.107 | 0.548 |

| Teaching evaluation | 2.500 | 1 | 14.274 | 0.001** | 0.273 | 0.957 | |

| Course planning and teaching methods | 0.943 | 1 | 5.429 | 0.025* | 0.125 | 0.622 | |

| Teaching problem-posing | 0.608 | 1 | 5.648 | 0.023* | 0.129 | 0.639 |

The dependent variables in Table 8 reveal statistically significant differences across all SEPTCT sub-dimensions between the experimental and control groups of preservice teachers. Specifically, the sub-dimensions of teaching algorithmic thinking (F(1-38)=4.554, p<0.05, ƞp 2=0.107), teaching evaluation (F(1-38)=14.274, p<0.01, ƞp 2=0.273), course planning and teaching methods (F(1-38)=5.429, p<0.05, ƞp 2=0.125), and teaching problem-posing (F(1-38)=5.648, p<0.05, ƞp 2=0.129) demonstrate statistically significant differences. These differences indicate high to medium effect sizes.

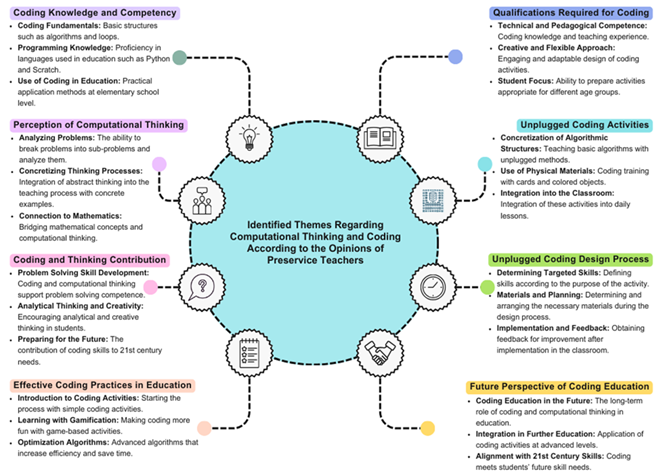

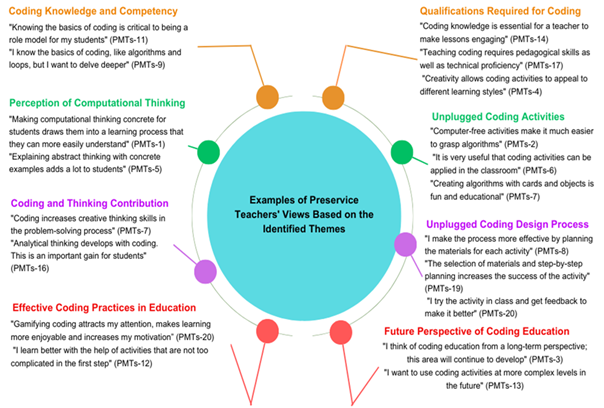

Figure 2 presents themes on the current situation based on preservice teachers' opinions. Specifically, preservice teachers' opinions were organised into eight themes, each containing three categories. The categories are coding knowledge and competency, perception of CT, coding and thinking contribution, effective coding practices in education, qualifications required for coding, unplugged coding activities, unplugged coding design, and future perspectives on coding education. Sample participant statements for each category are presented in Figure 3.

A general evaluation of preservice teachers' opinions in Figure 3 suggests that supporting design-based CT instruction enhances candidates’ pedagogical approaches and strengthens their inclination towards CT processes. Additionally, coding knowledge encourages deeper learning, supports abstract thought, and fosters creative and analytical thinking. It increases motivation by making learning enjoyable, adding interest to lessons, and enhancing pedagogical skills. Furthermore, coding knowledge offers an innovative perspective on diverse learning styles, facilitates comprehension of algorithms, improves process efficiency, and is anticipated to become increasingly essential in the future.

4. Discussion

This study comprehensively investigated the effect of the DBL approach on preservice teachers' CT skills and their self-confidence in teaching these skills. The findings show that DBL is highly effective in developing preservice teachers' CT skills and enhancing their competence in teaching these skills.

The post-test CT skill scores of preservice teachers in the experimental group were significantly higher than the control group’s scores. CT skills were analysed in the sub-dimensions of creativity, algorithmic thinking, cooperativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving, with significant differences favouring the experimental group in each dimension. These results validate DBL’s contribution to individuals' thinking and problem-solving skills, as shown in studies by Barab and Squire (2004) and Brennan and Resnick (2012). In particular, improving algorithmic thinking and problem-solving skills suggests that DBL significantly enhances PMTs' systematic thinking and approach to problem-solving processes. The effect of DBL in education lies in its encouragement of creative and innovative thought processes. Grover and Pea (2013) stated that teachers require support in CT education, their competence in this area should be enhanced, and they should be provided with the necessary tools and materials for CT instruction. This study offers guidance on integrating CT more effectively with pedagogical strategies and curriculum in elementary teacher education programs to enhance PMTs' CT proficiency. It highlights the need for strategies to help preservice teachers acquire these skills while enhancing their self-confidence and pedagogical competence. Development in the creativity and critical thinking sub-dimensions indicates that DBL promotes both problem-solving skills and the ability to explore diverse solution methods. DBL encourages more active participation from preservice teachers in the learning process and fosters the development of innovative strategies in teaching (Avşar, 2023; Israel & Lash, 2020).

The study further reveals that the DBL approach increases PMTs' self-confidence in teaching CT. Preservice teachers in the experimental group obtained significantly higher scores than the control group in the sub-dimensions of algorithmic thinking, evaluation, course planning, teaching methods, and problem-posing. This finding supports researchers’ findings on student competencies and pedagogical development (Boom et al., 2022; Kolodner et al., 2003; Lockwood & Mooney, 2018; Looi et al., 2024; Navarro & de Sousa, 2023; Shute et al., 2017; Shulman & Shulman, 2009). The increase in PMTs' self-confidence enhances their competence in teaching CT skills, supports the effective use of teaching strategies, and improves their management of educational processes for students. Improvement in assessment and lesson planning shows that DBL strengthens PMTs' skills in structuring their teaching processes and enables them to anticipate potential difficulties better. Therefore, DBL can be considered an important tool for developing preservice teachers' teaching competencies and pedagogical strategies (Avşar, 2023; Pei et al., 2018). The study’s findings align with previous literature emphasising the synergy between DBL and CT development (Grover & Pea, 2013; Kolodner et al., 2003). In particular, the impact on pedagogical self-efficacy echoes findings by Navarro and de Sousa (2023), who noted that hands-on design activities empower teachers to translate CT into classroom practice.

Effect analyses reveal a high effect size in both CT skills and teaching confidence in CT between the experimental and control groups. These significant differences within and between groups demonstrate that DBL is an effective model for teaching and developing CT skills (Hmelo-Silver, 2004; Papert, 1980). The DBL approach supports the development of advanced cognitive processes such as abstract thinking, analytical problem solving, and collaborative learning in PMTs. Additionally, these findings show that DBL is effective in knowledge acquisition and in fostering in-depth understanding through the teaching process. The high effect sizes in the creativity and problem-solving dimensions reveal that the thinking skills cultivated by PMTs through DBL receive strong support (Navarro & de Sousa, 2023). These results confirm DBL as an effective method for equipping students with a broad range of problem-solving and critical thinking skills. While the results strongly support the effectiveness of DBL, it is important to consider whether the improvements are solely attributable to the methodology itself. Alternative explanations, such as increased instructor attention, participant motivation, or the novelty of the experience, could also have contributed. Thus, future studies should control for this potential confound.

Evaluations of PMTs’ opinions show that design-based CT teaching enhances their pedagogical skills and aptitude for CT processes. PMTs’ views highlight the positive effects of the DBL approach in education and suggest that DBL, an innovative approach to developing pedagogical and technical skills in preservice teachers, should be more widely integrated into educational programs. The themes identified from participant responses, particularly those emphasising collaboration and reflection, mirror the improvements observed in cooperativity and critical thinking subdimensions. This convergence strengthens the internal validity of the results and supports the interpretation that DBL influenced both skills and pedagogical perspectives.

4.1. Limitations and implications for future research

Although the study’s findings revealed significant results, the research has limitations. Firstly, the study was conducted with a specific sample of PMTs. This limitation restricts the generalizability of the findings and indicates the need for similar studies in groups with diverse demographic or geographic characteristics. The DBL method used in this study was implemented as an additional activity to preservice teachers' existing education programs. However, fully integrating such an intervention into the curriculum may depend on student density, institutional resources, and educators' capacity to apply this method. Similar studies with larger sample groups across various education levels (primary school, middle school, high school, etc.) would be beneficial following future research recommendations.

Additionally, evaluating preservice teachers' teaching performance after acquiring CT skills is crucial. This is an important research area for examining the impact of DBL on classroom teaching processes. As technology rapidly evolves, digital tools and environments available for DBL-based CT teaching are expected to diversify. Integrating digital tools into teaching processes and examining their effects on the effectiveness of DBL represent valuable areas of investigation for future studies. Such studies can enhance preservice teachers' digital literacy and pedagogical technology skills by exploring more effective ways to incorporate technology in education. Nevertheless, this research has virtues and implications for the future, allowing the group of researchers to further develop in CT.

Conclusion

This study confirms the effectiveness of the DBL approach in enhancing CT skills and teaching self-confidence among preservice teachers. The findings demonstrate that DBL supports a broad range of cognitive and pedagogical competencies, from creativity and algorithmic thinking to lesson planning and instructional design.

DBL provides knowledge acquisition and facilitates deep understanding and active engagement in learning. The significant gains in both technical and pedagogical aspects highlight the potential of DBL to transform teacher education and better prepare future educators for the demands of 21st-century classrooms.

The alignment between quantitative data and qualitative insights reinforces the validity of the findings. By integrating DBL into elementary teacher training programs, institutions can promote more innovative, reflective, and effective teaching practices. As the educational landscape continues to develop, adopting approaches like DBL will be essential for equipping teachers to foster CT skills in increasingly complex learning environments.

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by National Funds through the FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., within the scope of the project Refª UIDB/05507/2020 and DOI identifier https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/05507/2020. Furthermore, we would like to thank the Centre for Studies in Education and Innovation (Ci&DEI) and the Polytechnic of Guarda for their support.

Authors' contribution

Conceptualization, P.T., D.K. and T.K.; data curation, P.T., D.K. and T.K.; formal analysis P.T., D.K. and T.K.; funding acquisition, P.T., D.K. and T.K.; investigation, P.T., D.K. and T.K.; methodology, P.T., D.K. and T.K.; project administration, P.T., D.K. and T.K.; resources, P.T., D.K. and T.K.; software, P.T., D.K. and T.K.; supervision, P.T., D.K. and T.K.; validation, P.T., D.K. and T.K.; visualization, P.T., D.K. and T.K.; writing-original draft, P.T., D.K. and T.K.; writing-review and editing, P.T., D.K. and T.K.