The social base of authoritarian and nationalist parties

In recent times we observe an increase of voting in authoritarian and nationalist (AN) parties in oldest democracies and most developed countries, including in the European Union (EU) that was founded with the objective of creating a supranational cooperative space and putting an end to war in Europe.1

The dimension of a political party depends on the historical and institutional contexts, and on the characteristics, practices and discourses of its leadership and activists, the party’s political programme and its organization, the role of the media, etc. A full study of current growth of AN parties requires the examination of compatibility and financial flows between national interests (military, political), economic groups, statist forces, conservative organizations, and authoritarian protagonists. For instance, in a paper named “Trump: authoritarian, just another neoliberal republican, or both?” R. Lachmann (2019) shows that the autocratic public image of the USA’s president and his decisions are a part of the overall strategy of the Republican party (and the economic elites that support it), which keeps fostering liberalism and becoming increasingly authoritarian and nationalist.

But in a democracy those compatibilities and financial support aren’t effective if AN parties can’t ensure a significant social base. Analysing the characteristics of the social base of AN parties is then decisive.

There exists a relevant literature on the social base of these parties (Golder, 2016; Arzheimer, 2012; Van der Brug and Fennema, 2007; Mayer, 2005). Some authors defend that AN vote is ideological, with specific proposals about policies on immigration, integration and law and order (Swyngedouw, 2001; Van der Brug, Fennema and Tillie, 2000; Eatwell, 2000), while others emphasize that this social base is irrational, with no specific values or policy preferences (Rydgren, 2011; Zhirkov, 2014).

For those who stress an ideological support, the development of this social base is explained by the growth of economic inequality (Lubbers, Gijsberts and Scheepers, 2002), by the escalation of relative deprivation (Dubet, 2017) and culture wars (Graeber, 2011), or by a cultural backlash to post-materialism (Inglehart and Norris, 2016). But despite the fact of being accepted that economic, social and cultural factors are interrelated (Inglehart and Norris 2016: 16), this interlacing is not theoretically and empirically addressed; a consistent and comprehensive approach that articulates those factors and that allows for characterizing, comprehending and explaining the growth of this sociocultural base is lacking.

The alternative explanation that sees an irrational behaviour of AN electors considering that these voters have “no specific values or policy preferences” may be challenged if we work on a theoretical ground that analyses dispositions and social orientations expressed both in rational and non-rational action.

Contributing to reduce this gap, we study the social base of AN parties grounded on a theory that articulates social and cultural dimensions. These dimensions are defined at levels that are both structural (social structure, mainly class structure, and cultural patterns) and individual (class location and individual dispositions, orientations, values and social representations). Individuals interiorize dispositions during their life experiences that are therefore shaped by the structural context of these experiences, and that are expressed in orientations, values, social representations and social practices. Social and cultural determinism, and individualistic and holistic reductionism are rejected in this model that seeks to ascertain relationships between its components in a heuristic mode (Almeida, Machado and Costa, 2006: 95-98).

Within the social dimension the conceptualization of social class follows the ACM model (Almeida, Costa and Machado, 1988; Costa, 1999). This model is built on prior contributions from E. O. Wright, A. Giddens, R. Erikson, J. Goldthorpe and L. Portocarero, G. Esping-Andersen, and P. Bourdieu, aiming to move beyond the objectivist/subjectivist and economicist/culturalist deadlocks. It is focused on the analysis of inequalities and differences within the division of labour and education, grounded on theoretically relevant and institutional indicators that are directly translated into/from official data and other class analysis models, resulting on a comprehensive and qualitatively descriptive class typology.

The cultural dimension is addressed through the analysis of human values, defined by S. H. Schwartz (2012) as trans-situational and general beliefs that motivate action. We complement this approach with a link to the concept of social orientations (Casanova, 2009; 2004). This last concept allows the operationalization of cultural structure (considered as socially structured and structuring of behaviour according to P. Bourdieu and A. Giddens), and the definition of “heteronomy”. With values and social orientations, we aim to grasp cultural characteristics that are long-lasting and difficult to change.

We study the social base of parties analysing party’s voters and joining a long research tradition that stresses significant variations of party voting with social class (P. Lazarsfeld, P. Converse, G. Michelat, M. Simon) and with values (R. Inglehart, S. Schwartz). This tradition is currently updated on the specific subject of AN parties by Rydgren (2013), Bornschier and Rydgren (2013), and Kalb and Halmai (2011).

We also build upon previous work focused on the French AN party “Front National” and the comparison of the socio-political situation in France, Portugal and the United States of America (Casanova and Almeida, 2018). Following this work, we expect to observe increasing inequality (especially in education) in welfare states in the EU despite the expectations of equality of opportunities and social inclusion that have been institutionally cultivated in these countries. The rise of inequality is breeding a political reaction in response to the failure of those welfare expectations, driven by deprived social classes threatened with social exclusion, mainly in education. Together with Rydgren (2013), Bornschier and Rydgren (2013), Kalb and Halmai (2011), and Mayer (2005) we expect that the social base of AN parties is essentially composed of this deprived population, namely less educated industrial and agricultural workers, and routine employees. A further original contribution is the expectation that the growth of AN social base is associated with the expansion of heteronomy. By this we mean a conformist social orientation that helps to understand values and cultural traits involved in authoritarianism and nationalism, the relation of AN voters with society, their attitudes towards immigrants, and why a socially deprived population is an effective Right-wing voter (Casanova and Almeida, 2018).

“Populist / non-populist”, “left / right”, “centre / extreme” and “radical / moderate” are controversial distinctions (Muis and Immerzeel, 2017; Mudde, 2016) eventually involving confounding and disguising notions. “Populist” in particular is an excessively syncretic term to classify a party. The indiscriminate use of “populism” to define political parties may dismiss as demagogic legitimate claims from the socially deprived, implicitly excluding them from democracy.

Given the need for clear definitions within this disputed topic, countries that have parties with evident AN characteristics were chosen focusing on sharper ideological content that has a clearer definition: support for a strong central power ruling over the “natural” differences that exist in society (authoritarianism) and for congruence between state and nation promoting a mono-cultural state (nationalism) (Mudde, 2007; Golder, 2016). The AN parties were selected among the “radical populist” parties listed by Mudde (2007), Van Kessel (2015), and Inglehart and Norris (2016).

We use individual level data delivered by the European Social Survey (ESS) that in addition to “vote” also provides pertinent indicators of social class and values.2 The analysis is centred in Round 8 of ESS, with data from 2016, but cross-temporal observation will also be introduced comparing Round 8 with earlier Rounds.3 Furthermore, we include contextual national level data on economic and educational inequalities, and on social mobility.

The countries being analysed were selected considering that we want to concentrate on older democracies and most developed countries in the EU. Eastern countries in the EU were not included since they belong to a recent democratization wave and they share a specific type of nationalism developing, at least partially, against previous Soviet supra-nationalism (Narozhna, 2004: 300). We privilege the countries with AN parties belonging to the five most voted parties in the country. We end up with eight countries/AN parties: Austria - Freedom Party of Austria, Finland - True Finns, France - Front National, Germany - Alternative fur Deutschland, Italy - Lega Nord, Netherlands - Party for Freedom, Sweden - Sveridgedemokraterna, and the United Kingdom - United Kingdom Independence Party. These are all populist radical or extreme Right-wing parties, where AN traits normally excel.4 The other four parties contemplated in each country were divided in two sets differentiating Left and Right parties.5

The concept of social class according to ACM model integrates socio-professional and socio-educational dimensions; the former is operationalized through the ESS indicators of occupation, employment relation and number of employees respondent has/had (tables A2 and A3, Annex), and the latter through the indicators of highest level of education (ES-ISCED, Educational Stage - International Standard Classification of Education) and years of full-time education completed.

Household’s total net income was also used as a supplementary indicator of economic resources.

Human values are operationalized in the ESS through the 21-item measure as a basis for the typology of 10 values designed by S. H. Schwartz.

Additionally, we analyse several ESS indicators of the relation with politics and human development, and attitudes towards immigrants.

The indicator of vote is the party people voted for in last national election.

Sociocultural characterization and comprehension of AN electorate

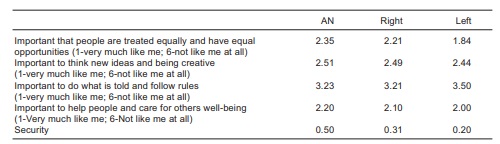

A deprived social position

The social class with the most weight among voters of AN parties is routine employees followed by industrial and agricultural workers, both representing 61,4% of the total of voters. These social classes and their global weight are smaller within Left and Right-wing parties (table 1). On the contrary, intellectual and technical professionals and supervisory employees, and entrepreneurs, managers and independent professionals have a significantly lower weight in AN voters compared to Left and Right-wing voters. The percentage of self-employed workers is high in AN voters but this is not characteristic since it remains relatively higher in the Right-wing voters.

Table 1: Social class (column percentage), education and income (mean values) in voted parties

Source: ESS8.

When we look at each country (table A4, Annex) we note that routine employees and industrial and agricultural workers are the largest social classes of AN supporters in Austria, France and Netherlands. For the other countries, routine employees are not so prominent in AN voting (nonetheless they are in a second place in Finland and Germany), but industrial and agricultural workers are always predominant within AN voters. We can also see (table A4, Annex) that the sum of industrial and agricultural workers and routine employees is systematically higher than 50% in AN parties, except in France (48.8%).

The highest level of education attained is significantly lower in AN voters, compared to Left and Right-wing voters (table 1), and this is valid within each country except in Finland, but here True Finns voters stand quite close in the second lowest position (table A4, Annex).

The analysis of household’s total income indicates that its lowest score is found in AN voters (table 1), while Left-wing voters show an intermediate result and Right-wing voters display a higher average income.6 The AN electorate has a lower income in almost all countries except in Austria, Germany and Italy; but in Austria and Germany AN voters have the second lowest average income and only Italy is a decisive exception with Lega Nord showing the highest income within all the parties (table A5, Annex).

Alienated, distrustful, critical

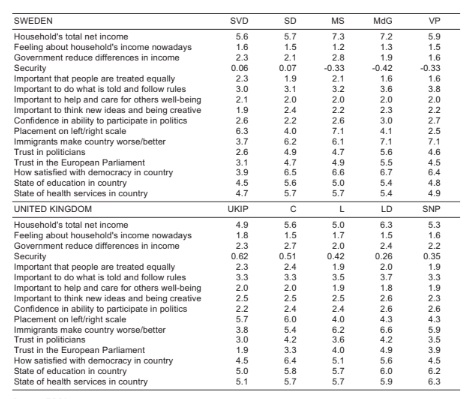

When we consider the relation of the respondents with politics (table 2) we observe that those who vote for AN parties are the least confident in their own ability to participate in politics, and this stands for Finland, France, Germany and the United Kingdom. In Italy and Netherlands this electorate is the second less self-assured, and in Austria and Sweden it is in third place (table A5, Annex).

Table 2: Relation with politics and human development, and attitudes towards immigrants in voted parties (mean values)

Source: ESS8.

In general AN electors place themselves on the Right wing of the political scale and a little above the supporters of the Right parties (table 2), but this Right-wing slight extremism of the AN electorate only pertains to Austria and Germany while in the other countries the placement of AN supporters is not as far-Right as the other Right voters (table A5, Annex).

Voters in AN parties are those who express lower trust in politicians and in the European Parliament, and are less satisfied with democracy in their country (table 2). This is valid for all countries except for trust in politicians and satisfaction with democracy in Italy (table A5, Annex).

Considering the relation with human development, we see that AN supporters are also those who feel more that they don’t live comfortably with their household’s income (table 2). This holds for most countries but not for Germany, where Alternative fur Deutschland takes a second critical position or Italy, where Lega Nord appears in the second-to-last position (table A5, Annex). But despite this critical feeling and their lower income, AN voters come after Left-wing voters when it comes to agreeing that the government should reduce differences in income (table 2). This intermediate attitude is visible in all countries except Italy where Lega Nord and Popolo delle Libertà voters are those who disagree the most to reducing differences in income (table A5, Annex).

When evaluating the state of education and health services in the country, AN supporters are the ones with a more critical opinion (table 2). This is valid for most countries excluding Austria and Germany; in Italy only the state of education follows the general rule (table A5, Annex).

If we measure the difference between mean values in AN, Left and Right-wing parties across all indicators in table 2 we realise that AN supporters are closer to Right-wing voters except in relation to trust in politicians and in European Parliament, satisfaction with democracy in the country, and the state of education where they stand nearer to the Left.

Having the lowest income, there is no surprise that AN voters feel less comfortable with their income; being those with the lowest education level (having less information and structured opinions), they feel less confident to participate in politics; and with the lowest income and education (less economic and cultural resources to access to and benefit from the services available), they express a more critical view about the state of education and health. But why do members of this deprived and critical population identify themselves, display similar attitudes, and vote for Right-wing parties, and do not demand more vehemently for the government to reduce differences in income?

To address this question, we will move beyond characterization to a comprehensive approach focused on the meaning of action of AN voters. As Immanuel Wallerstein emphasizes when reflecting on why do workers vote for right-wing parties, we must search beyond the concept of “false consciousness” and “try to discern how these others envisage for themselves what is their self-interest” (Wallerstein, 2017). With this purpose we build on values and social orientations as intermediate factors between social positions and social practices, according to the aforementioned theoretical framework.

Heteronomous and exclusionary

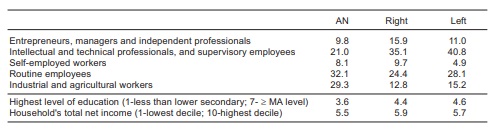

One of the main elements usually put forward to differentiate Left from Right-wing politics is equality: it is argued that Left-wing parties value equality more than Right-wing parties (Giddens, 1998).7 When we draw on the indicator of the human value of equality designed by Schwartz in the ESS8 (table 3), we see that AN voters are the ones who give the least importance to this value.8 And this is true for all countries except Italy (where Lega Nord comes after the Popolo delle Libertà in this relative devaluation) and the United Kingdom (where UKIP comes after the Conservative Party).

Therefore, there is significant conformity with inequality interiorized by the social classes that characteristically support AN parties, and the unveiling of this conformity helps to understand why voters of deprived social classes place themselves on the Right side of the Left-Right scale, are in general closer to Rightist attitudes, and vote for Right-wing parties.

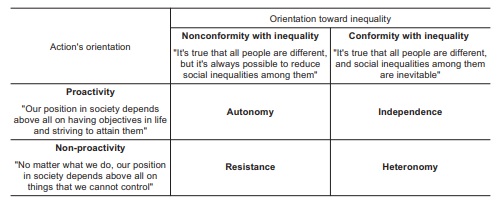

Conformity with inequality has been studied drawing on the concept of “social orientations”. Social orientations are envisaged to measure social culture, the incorporated dispositions in individuals of their relation with the structure of social positions, associating the concept of habitus developed by P. Bourdieu and the reflexive capacity of social actors widely discussed by A. Giddens and P. Bourdieu, among others. Social orientations are operationalized through the combination of indicators of the orientation towards inequality and action’s orientation as presented in figure 1. To define the respondents’ social orientation, they must identify themselves in a questionnaire with one of the two opposite beliefs deployed in each indicator (“non-conformity / conformity with inequality” and “proactivity / non-proactivity”), its combination resulting on four ideal-typical social orientations: autonomy, independence, resistance and heteronomy. A fifth social orientation is added, integrating those respondents that didn’t answer to at least one of the two questions. It has been extensively verified that these respondents live in the poorest conditions and are the least informed, reflexive and participative in civic and political life, thereby expressing what is defined as the social orientation of exclusion (Casanova, 2009; 2004).

Within this model conformity with inequality can be proactive or non-proactive. As we can see in table 3, AN voters are those who give less importance to thinking new ideas and being creative, an indicator for proactivity.9 This occurs in most of the countries except Finland, Netherlands and the UK (where AN supporters appear in a second position), and in Sweden where Sveridgedemokraterna voters are those who show higher proactivity (table A5, Annex).

In short, since the AN electorate is comparatively more conformist with inequality and less proactive, this means that it is fundamentally characterized by the orientation of heteronomy.

Heteronomy is predominantly found in deprived social positions and it is the paradigmatic conformist orientation, logically opposed to autonomy, and combining conformity with inequality and conformity with hetero-determination of one’s social position (Casanova, 2009).

Heteronomy is, then, essentially associated with passive or reactive social action. It has been verified that people characterized by the orientation of heteronomy scarcely participates in political life and in the work of institutions, limiting themselves essentially to complying with rules (Casanova, 2009). Table 3 shows that AN electors have an intermediate position when they are asked about the importance of doing what they are told and following rules, but they are very close to the Right-wing voters who score just a little higher. And in Italy, Sweden and the United Kingdom AN voters are among those who give the highest importance to this value (table A5, Annex). Given the distance from politics and institutions found amid people characterized by heteronomy, voting appears as an exceptional compliance to civic and political rules and may be fundamentally intermittent and reactive.

In table 3 we see that helping people and caring for others’ well-being, an indicator of solidarity, reached its lowest score with AN voters. This evokes traits like “selfishness” and “unwilling to pay taxes that go to the unfortunate” found by Hochschild among the supporters of Tea Party, that also have AN traits and would decisively contribute to elect Donald Trump in the USA (Hochschild, 2016: 234). Lower solidarity indicates higher closure in restricted circles and cultural isolationism, and when combined with social conformity and within a deprived social position means that it is primarily a dominated and protective cultural isolationism. This is valid for all countries but Italy where Lega Nord is second after Popolo delle Libertà (table A5, Annex).

And the human value of “Security” excels in AN supporters, being more than double the average in the Left voters (table 3). This striking valuation of security and a protective cultural isolationism, adding to compliance with rules indicates that this population relies on rules mainly to protect themselves and their closest relations. This doesn’t apply entirely in Germany and Sweden however there AN electors come immediately in second place (table A5, Annex).

In sum, the prevalence of deprived social positions and the orientation of heteronomy in AN voters allows us to understand their alignment with Right-wing parties and other attitudes. Conformity with inequality usually entails accepting and naturalizing the existence of “superior” and “inferior” sociocultural categories. This conformity and the deprived social position of AN voters imply that they may consider the probability of not being part of the “superior”. Yet, their tenuous claim for the government to reduce differences in income suggests that although they are in a deprived and dominated social position, they may not like to depend on the government. This suggests that we are dealing with self-confident conformists, raising traits such as “pride”, “capacity for sacrifice and endurance”, and the valuation of “honour” again observed by Hochschild in Trump’s electors (Hochschild, 2016: 234).

Significant compliance with rules, self-confidence, and reactive and critical attitudes allows us to understand why this electorate is often described as moralist. Heteronomy, passive / reactive action, compliance with rules and the “capacity for loyalty” also identified by Hochschild within Trump’s electorate (ibid.: 234) helps to comprehend its support for authoritarianism. Heteronomy, self-confidence, moralism and critical attitudes in relation to politics and human development may signify that their expectations are not fulfilled when it comes to those to whom they delegate initiative and decisions-making abilities in society; and this helps to understand why they might engage in Manichean party programs and political discourses based on the allegation of the purity of the people and the corruption of elites.

Since AN electors characteristically have deprived social positions, a conformist orientation, and so expressively value the security that a strong government may ensure, this means that they may feel threatened by social exclusion, and this is a likely concern given their precarious inclusion in society. And if they feel exposed to social exclusion and are especially critical of the state of health and educational services, being deprived, conformist, protective-centred, not liking to depend on the State indicates that this population miss major means to improve their own well-being, being dependent and unprotected from social exclusion.

A relative lack of solidarity, adding to conformity with inequality (and its expression in the naturalization of sociocultural “superiority” and “inferiority”) sets the cultural ground for nationalist, xenophobic, racist, sexist and homophobic attitudes within this population. Not only inequalities but also differences in general tend to be hierarchized, reduced to a division between “superior” and “inferior”. Once this is coupled with lower sense of solidarity, self-confidence, the prospect that different people will not comply to the rules which AN voters know and acknowledge, and a perceived risk of their own social exclusion, then what is felt as culturally different is considered a threat to their culture and to their precarious integration in the “socio-cultural hierarchy”. Therefore, we may expect that the AN electorate develops exclusionary predispositions against those they think represent this threat.

In fact, these voters are those who more expressively say that immigrants make a country worse (table 2) and this is evident for all countries (table A5, Annex). And there is a higher statistically significant correlation according to the predicted direction between this attitude and the value of equality (that indicates a varying disposition to naturalize inequality).10

Thus heteronomy (the low scores for equality and creativity) and low solidarity are significantly associated with attitudes towards immigrants enabling us to comprehend AN electorate’s alignment with exclusionary political discourses and policies targeting this segment of the population.

Explaining the expansion of AN electorate

On the edge of social exclusion

AN voters have deprived social positions. But are they as deprived as immigrants? How do they compare to those who are in a situation of social exclusion?

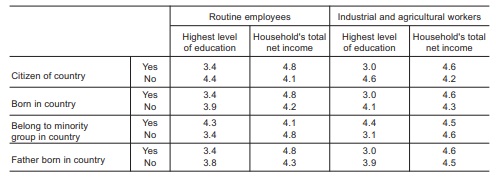

We cannot directly compare AN voters with immigrants using data of the ESS8, but it is possible to approach this issue by comparing AN supporters with those who are or are not citizens of the country, those who are or are not born in the country, those belonging or not to minority groups, and those whose father is or is not born in the country (table 4).

Table 4: Social class (row percentage), education and income (mean values) of “natives” and “non-natives”

* Social classes are displayed by their initials

Source: ESS8.

Within the population that can be considered “native”, entrepreneurs, managers and independent professionals, intellectual and technical professionals, and supervisory employees, and self-employed workers have greater weight than in the “non-natives” where industrial and agricultural workers and routine employees are comparatively larger.11

On average “natives” have lower education but higher income than “non-natives”.

And whatever the degree of development of the original country of “non-natives” (table 5) they always have higher education and lower household income than “natives” (table 4).12

Table 5: Education and income of citizens from different parts of the world (mean values)

Source ESS8.

When we focus on industrial and agricultural workers and routine employees we note that within the social classes where most AN voters are positioned we have the same scenario as on the national level: within the social classes where “non-natives” have a higher weight, they have lower household incomes but higher education levels than “natives” (table 6).

Table 6: Education and income in routine employees, and industrial and agricultural workers of “natives”and “non-natives” (mean values)

Source: ESS8.

Bearing in mind that mean values for education and household’s income in AN voters are 3.6 and 5.5 respectively (table 1), we grasp two important further results. First, this electorate has a higher income compared to “non-natives” from all over the world (table 5) and to industrial and agricultural workers and routine employees in general (table 6), and equivalent income to the average of “natives” (table 4). Second, AN supporters have higher education levels than “natives” in industrial and agricultural workers and routine employees (table 6) but lower education compared to “natives” and “non-natives” in general (table 4), whatever the degree of development of the country of origin (table 5), and “non-natives” in industrial and agricultural workers and routine employees (table 6).

So, AN electors are in an equivalent situation to “natives” in general, a little better than industrial and agricultural workers and routine employees, and considerably better than “non-natives” in terms of income, but significantly disadvantaged when it comes to education compared to “natives”, but mainly with “non-natives”, including those who come from developing countries.

These results suggest that both “non-natives” and “natives” belonging to deprived classes may endure feelings of relative deprivation, economic in the former and educational in the latter.

Despite its deprived social position, these AN supporters do vote. Voting is a significant indicator of social inclusion. In order to have a fuller picture of the degree of deprivation of AN voters we will compare them now with those who do not vote, assuming that on average non-voters are by and large in a situation of social exclusion.

Data in table 7 confirms that people who do not vote have significantly lower socio-professional, educational and economic resources than those who vote.

Table 7: Social class (column percentage), education and income (mean values) of voters, non-votersand AN voters

Source: ESS8.

When we compare AN voters with non-voters (table 7) we observe that AN electors exhibit a slightly lower weight in deprived social classes (61.4% compared to 64.5% in non-voters) and higher education, and also a noticeably bigger household income. This means that the AN electorate is quite close to a social exclusion situation essentially in terms of educational resources contributing to explain their extreme critical attitude towards the state of education in their country.

Thus although these AN supporters do vote, showing a defensive-reactive - not passive or uncritical - political behaviour, and assuming the most sceptical posture about equality and stronger exclusionary attitudes towards immigrants, they live at the edge of social exclusion and this is mainly due to their low and deteriorating educational resources.

Growing inequality and heteronomy

According to previous research it is expected that rising inequality will explain growing heteronomy and the expansion of AN electorate (Casanova and Almeida, 2018). If heteronomy is defined by conformity with inequality, we expect that the increase of inequality contributes to the diffusion of heteronomy: the growth of inequality reinforces sociocultural alienation of those in deprived social positions, who incorporate (accommodating and endorsing) the systematic frustration of actions and expectations devoted to the improvement of their life conditions.

To verify this proposition, we analyse the trajectory of inequality by contemplating national level data on economic and educational inequality, and social mobility in official reports, while considering education and income at individual level in ESS.

Recent data demonstrates that economic inequality in disposable income has grown since mid-1980s in Finland, Netherlands, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom (OECD, 2017: 8). This study doesn’t have enough data for Austria and Sweden but other reports show that the global trend in these countries is the same (Verwiebe et al., s/d: 12; Atkinson et al., 2017). France appears as an exception in the OECD report; nonetheless more data reveal that inequality in disposable income falls between 1960 and 2002, and starts mounting since then (Hasell, s/d). It is also evident that these eight countries are amongst those where the wealth share of the bottom 40% of the population is currently lower than Europe’s and the OECD’s average in most cases (OECD, 2017: 10).

The analysis of absolute mobility rates across cohorts from 1927 until 1977 in European countries show that the percentage of the upwardly mobile decreases systematically within that period in France and Sweden, and since the cohort born in 1946-1964 in Austria, Germany, Finland, United Kingdom and Netherlands, this accompanied by a generalized increase of downward mobility (except in Finland, mainly characterized by increasing social immobility) (Eurofound, 2017, Annex 4).13

Data from a report on equity in education reveals that “average levels of educational attainment rose worldwide during the past few decades, but more so in OECD countries than in developing countries” (OECD, 2017: 77). Yet, in OECD countries “large socio-economic differences in educational attainment, for example, in the completion of tertiary degrees, have not narrowed over the past few decades, despite the expansion of education observed during this period” (ibid.: 59).

It is also found that there is a diminishing upward educational mobility among cohorts born between 1946 and 1989 in 21 countries that include Austria, England, Finland and Sweden (ibid.: 81). In France, Germany and Netherlands there are some variations, and only in Italy did the trend in upwardly mobile adults increase over time (ibid.: 82).

When we examine trends in tertiary education among cohorts born between 1946 and 1989 (33 countries) we note that, “because gains were larger among those with highly educated parents, the gap in tertiary attainment between adults with highly educated parents and those with low-educated parents grew over time” (ibid.: 86). Here Italy is a markedly typical case (ibid.: 87), and Austria, England, France, Netherlands and Sweden follow the general trend too. Finland seems to display a minor improvement in equity (ibid.: Annex 2.26), and the same for Germany but this is mainly because “the probability of completing tertiary education decreased […] regardless of their parent’s level of education. Greater equity is achieved because the decrease in likelihood is slightly greater for adults with highly educated parents than for adults with low-educated parents” (ibid.: 90).

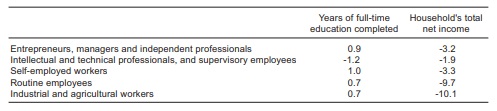

National level data doesn’t allow us to observe the trajectory of inequalities comparing different social classes, “natives” and “non-natives”, or AN, Left and Right-wing voters. With this purpose we return to ESS. First comparing data on education and income of social classes in rounds 1 and 8, allows for the analysis of the trajectory between 2002 and 2016, after analysing the intergenerational trajectories of education within ESS8.

Education rises for all social classes between 2002 and 2016 except for intellectual and technical professionals, and supervisory employees, but these remain the social class with the highest education (table 8). The smallest growth is observed in industrial and agricultural workers and routine employees.14

Table 8: Variation between 2002 and 2016 in education and income according to social class

Source: ESS1-8.

Household incomes decreased for all social classes, but quite unequally, with industrial and agricultural workers and routine employees loosing at least the triple of the other social classes (table 8).15

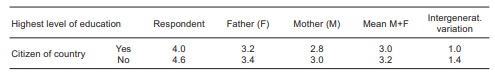

If we consider the intergenerational variation of education in “citizens of country” and “non-citizens” we see that the level of education is higher in the family’s background and it grows more significantly among “non-citizens” (table 9). This means that immigrants may have a more favourable educational background and are increasing their education levels faster. Previous studies already pointed to a significant increment in education among immigrants compared to natives in developed countries (Eurostat, 2018; Oberdabernig and Schneebaum, 2017).16

Table 9: Intergenerational variation in education of “citizens of country” and “non-citizens” (mean values)

Source: ESS8.

And when we compare intergenerational variation in education amongst electorates we see that the lowest progress is in the AN electorate (table 10).17

When democracy incubates inequality and heteronomy - a fake democracy?

The present analysis is not about AN leadership and activists, which would require a different research design, but about those who more widely vote for parties with AN traits.18

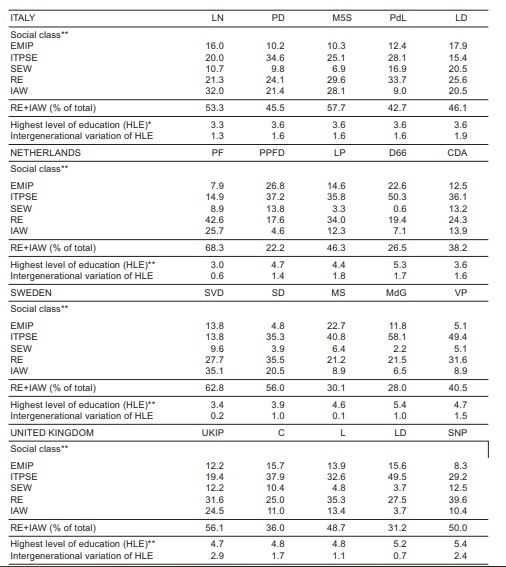

As expected, social class following the ACM model constitutes a highly significant factor to explain voting patterns of five major parties in all countries under analysis.19

We confirmed that, comparing to Left and Right-wing voters, the AN electorate in these countries is characterized by an over-representation, both in absolute and relative terms, of deprived social classes (industrial and agricultural workers and routine employees), exposing a structural polarization between AN voters and the rest of the voters. In AN voters the proportion of industrial and agricultural workers - which appears as the typical social class of AN voting in the EU in 2016 (including Italy) - doubles and the percentage of intellectual and technical professionals and supervisory employees decreases to half. The supporters of AN parties are also those with the lowest level of education and household’s income.

We also substantiated the relevance of the concept of social orientations to understand social culture, and we ascertained that the AN electorate is characterized by heteronomy, the paradigmatic conformist social orientation defined here by a low score of the human values of equality and creativity.

Heteronomy is likewise considered as the foundation of ethics for the philosopher E. Levinas who defines it as a morality previous to individual conscience, a norm of norms, founded in the responsibility towards the “other” and expressed in passivity; these features seem to correspond to a large extent with the cultural aspects of the social orientation of heteronomy.

When combined with the valuing of compliance with rules and the undervaluing of solidarity, heteronomy allowed us to comprehend well-known cultural traits and attitudes associated with authoritarianism and nationalism. Authoritarianism in industrial workers was previously discussed, among others, by S. Lipset (1959); currently this authoritarianism is fuelling Right-wing parties and we verified that this alignment is correlated with a particularly low valuing of equality associated with the incorporation of a conformist orientation in relation to inequality among industrial and agricultural workers.

So, the spread of the social orientation of heteronomy in a population seems to be the cultural terrain for authoritarian and nationalist leadership and activism to prosper.

If we look at sociocultural characteristics of the AN electorate in each country, we find some deviations to the general pattern, but these are minor deviations involving a minority of countries, and only Italy seems to be a distinct case. Despite the diversity of historical and institutional national contexts, political systems, and party’s organizations and leadership we clearly observe a common class base and shared relevant cultural traits in AN electors in the eight countries, justifying our objective of searching for a transnational reasoning and explanation within older democracies and most developed countries.

Our results also show that we can identify specific values amid the AN electorate and, with the support of a comprehensive approach, interpret their political preferences; this outcome stands in opposition to Rydgren (2011) and Zhirkov (2014) who considered this population as “irrational”. Yet, the heteronomous culture and reactive behaviour found in AN electorate means that they may not have an “ideology” in the sense of a systematized set of values expressed on an explicit socio-political agenda and respective policy preferences.

Our explanatory hypothesis has also been corroborated. Whether we consider national trends, the trajectory between 2002 and 2016, or intergenerational trajectory we observe growing inequality and downward social mobility in the eight countries. And these processes are essentially undermining the economic and educational conditions of industrial and agricultural workers, and routine employees, and in particular of those who are voting for AN parties in these social classes who are caught in a trajectory of social exclusion, mainly in education.

These eight countries are among those with highest inequality-adjusted human development index and lower inequalities in the world and in the EU (UNDP, 2018). Therefore, the trajectory of inequalities has specific effects on the expansion of heteronomy and AN voting beyond present degree of inequality in the context of older democracies of developed countries. And our results may be valid for other developed countries with AN electorate like the United States of America, Canada, etc.20

This also means that law and sanctioning measures against authoritarian organizations and protagonists tend to be inefficient when democracy incubates inequality.

Thus, according to our results, if there is a “culture war” involving AN electors it may be against those who value equality, creativity and solidarity more, and do not value following rules as highly. This hypothetical “culture war” may correspond, at least in part, to the previously found class polarization related to AN voting between industrial and agricultural workers, on one side, and intellectual and technical professionals and supervisory employees, on the other side. Since the predominant social orientation in intellectual and technical professionals and supervisory employees is autonomy (Casanova, 2009; 2004) - the opposite social orientation to heteronomy - this helps to understand the cultural tension between AN supporters and this elite.

Autonomy is considered by E. Kant (following Aristotle and J.-J. Rousseau, and in opposition to E. Levinas) the supreme principle of ethics, entailing dignity and rationality, freedom from all dependency but reason, and considering that being moral is being autonomous. We can also find a focus on autonomy in the work of C. Castoriadis who defines it as a cultural project, a process closely linked to equality; and, in an implicit mode, in the thought of P. Bourdieu who evokes modernity when referring to the process of autonomisation (imposition of auto-nomos, with “nomos” being the “fundamental law” or “rules of the game”) of fields, following the case for the field of literature.

This suggests that the difference between heteronomy and autonomy, whether in the philosophical sense as ethical principles, whether in sociological terms as social orientations, is closely associated with the classical differentiation between tradition and modernity simplified in dichotomies like pre-capitalism / capitalism in K. Marx, community / society in F. Tonnies, mechanic / organic solidarity in É. Durkheim, and non-rational / rational social action in M. Weber. So, the tension between AN electorate and intellectual and technical professionals and supervisory employees may be interpreted as a tension and a difficulty in communication between traditional and modern culture. Recalling the previous statement on the association between increasing inequality, the expansion of heteronomy, and the spreading of authoritarianism and nationalism this also means that modernity, as a structural process, may lose substance when inequality grows.

Being socially conformists, if AN voters feel relative deprivation this will involve as a group of reference not so much the dominant classes but mainly those with whom they interact and compare more directly. Being mostly industrial and agricultural workers and routine employees, AN supporters may compare to “non-natives” that have significant weight in these social classes (table 4). Based on our data, we can say that when “natives” compare themselves to “non-natives” within industrial and agricultural workers and routine employees they may realize that they have a higher household income but inferior education (table 6). Furthermore, if income and educational condition of industrial and agricultural workers and routine employees is failing when compared to other social classes (table 8), “natives” in general are not increasing their education as fast as their “non-native” co-workers (table 9). Therefore, and considering that in ESS data AN electors are predominantly “natives”, their specific social position is globally deteriorating in relation to both “non-natives” in general and “non-natives” in industrial and agricultural workers and routine employees. And relative deprivation in AN electorate comparing to “non-natives” may be above all educational, also taking account of their extreme critical attitude towards the state of education.21

How can we explain the increase in education of “non-natives” in the countries under analysis? Is it, at least partially, the result of the current strategies by states and organizations in most developed countries to capture “cheap” excellence in qualification from abroad, enrolled in a competition for supremacy within the so called “knowledge society”? Are these countries benefiting from the efforts of students and educational systems in other countries, at the expenses of investing in their own educational system and allowing bigger inequality of opportunities in education within their borders?

If it is so, the irony is that in those countries that are increasing the capture of excellence in qualification from abroad (“brain-gain”), neglecting equality of opportunities especially in education at home, and preventing non-qualified immigration, AN voting may continue to enlarge. And in those countries that are affected with the “brain-drain”, their development will be negatively affected, their employment will contract, and socio-political unrest and emigration for developed countries may surge.

AN supporters react in an exclusionary mode to “non-natives” but, since AN voters are socially conformists, with low confidence in their ability to participate in politics and negligible involvement in institutions and politics - therefore acting on the margins of citizenship - this exclusionary disposition is originally a reaction to those who have increasingly higher education levels and job opportunities, and are supposed to represent a threat to their social inclusion. AN supporters are the least solidary when compared to Left and Right-wing voters. However, they still state that solidarity is important (table 3). This exclusionary attitude is essentially a circumstantial symptom observed within deprived social classes undergoing educational deterioration and relative deprivation when comparing themselves to their “non-native” co-workers, and are threatened with social exclusion, all this ultimately associated with growing inequality. The decisive political question is: are we acting on the symptoms or on the cause?

If there is a broad “cultural backlash” - where the typical AN electorate is a protagonist simultaneously with other sociocultural segments of the population, altogether expressed in a “generalized and intensive fall on trust in political institutions and agents, mostly in the European Parliament, and on satisfaction with democracy” (Casanova, 2018: 210) - this backlash will surely have some roots in the contradiction between the expectations of growing equality of opportunities and social inclusion institutionally promoted in the EU and the reality of increasing inequality, downward social mobility, and social exclusion. All this is undermining basic objective requisites for democracy like the spread of middle classes, the reduction of poverty, and the promotion of equality (Lipset, 1958: 103, 105). That is to say that if we are observing a “cultural backlash” it will be at least in part against a “democracy” that incubates inequality and heteronomy. Are AN voters anti-elite because they think that elites are illegitimate, rulers failing the rules of democracy, corrupted in the promotion of equality and social inclusion?

Since 2016 the situation seems to be changing, as the contexts move quickly making the diagnosis equally fragile and dependent of successive conjunctures.

While it appeared, for several analysts, that the decadence of central and traditional parties in European policy was a continuous and inevitable process in favour of the far right and AN rise, subsequent elections results seem in general to contradict those views.

In France, for instance, recent local elections showed that the Front National lost a substantial number of their voters. And who won? The environmental parties with a strong support of the younger generations.

This robust presence of a voting youth connected with the “Greens” was already visible before the pandemic, but it seems to survive it as recent surveys in Germany confirm.

In more general terms, the so called “green wave” has affected several European countries and seems to progress not only at the expense of the far right but also of the traditional parties, those trying to adapt as fast as possible to the current times.

Besides the political rise of new generations, which has equivalence in other parts of the world including the USA, it is necessary to invoke different societal dimensions to grasp the apparent losing of strength of the European right in some of its countries, or its eventual resilience.

One of the favourable circumstances that feeds authoritarianism and nationalism, as we saw, is the deepening of resources inequality in each country. It is impossible to predict what will be the economic recovering of the pandemic and how fast it will occur. But it seems clear, for the moment, that it did not bring more equality. It must be said that the general opinion of Europeans seems to go in the direction of more powerful involvement from the European Community, mainly on the health front. This results from a survey in June 2020 solicited by the European Parliament where a clear majority of respondents asked for stronger community budgets to respond both to health problems and economic consequences of pandemic.

The political interventions in each country to combat Covid-19 and recover economies are under close popular scrutiny on a daily basis. The results of those evaluations will certainly have reflections on trust in institutions and in the outcomes of future elections. If trust is reinforced, AN support may lose momentum. And, again, new generations may be decisive in eventual game changing.

Finally, there are more structural trends. A social re-composition developing in Europe for some decades now goes in the sense of strengthening the so-called knowledge society. Apart from other dimensions and consequences, this implies the continuous growth of social classes that are more educated, namely intellectual and technical workers which are in opposition to heteronomy.

In the medium/long term we can expect, therefore, that this will also play against the affirmation of authoritarian and nationalist parties.