Introduction

Over the last 20 years, the phenomenon of fear of crime has become a popular research topic, especially in the United States and European countries (Chadee et al., 2017; Farrall, Jackson and Gray, 2009; Goodey, 2005; Özasçilar and Ziyalar, 2015; Shoham, Knepper and Kett, 2010). Over time, the fear of crime has become a more important consideration than crime itself because the fear of crime directly affects quality of life, public security and psychosocial health. However, while the number of studies related to the fear of crime in communities has been increasing, few studies to date have focused on fear of crime among university students. In fact, university students may be vulnerable to a greater risk of some crimes, such as sexual assault, violence and threatening behaviour due to their greater involvement in social activities. Also, substance and alcohol use may be more common among university students (Dahod, 2009; Tyler, Schmitz and Adams, 2015). For example, a 2017 study conducted in a private university in the United States, using a sample of 3,977 full-time graduate and undergraduate students, found that nearly one in eight students had been subjected to unwanted sexual incidents at the university (Campbell, Sabri and Budhatoki, 2017). Another study of 16,979 undergraduate university students found that, out of 7,032 (41.9%) students who had been sexually active in the past 12 months, 16.3% reported having experienced physical or sexual intimate partner violence, 15.4% among men and 17.2% among women. Approximately 11.3% of men and 10.4% of women reported being the victim of physical intimate partner violence, while 9.3% of men and 11.3% of women reported having experienced sexual intimate partner violence (Pengpid and Peltzer, 2016).

These studies suggest that university students might experience significantly higher levels of criminal victimisation than previously thought. Consequently, analysing fear of crime amongst university students is important because some studies suggest a significant relationship between victimisation and fear of crime (Fox, Nobles and Piquero, 2009; Tseloni and Zarafonitou, 2008). Besides observing victimisation, the current study also aims to evaluate a number of significant parameters as identified by the fear of crime literature. These parameters include sex, nationality, living area, and disorder. This study will examine how these parameters describe the fear of crime of youth population in the university. While there are several campus-based fear of crime studies, there are few international studies in this context. Moreover, the studies that do exist in relation to university students are focused on fear of crime in campus life, and are not specific to students’ fear of crime in general.

Most fear of crime studies rely on survey data from the general population. As a consequence, a number of key determinants have been identified, including sociodemographics, prior victimisation experiences and physical or social disorder. However, studies of university students’ levels of fear of crime, and factors influencing their fear levels are highly underrepresented (Xiong et al., 2017). In fact, there have not been any studies to date about fear of crime among university students in Northern Cyprus. Therefore, this study will help to shed light on the students’ thoughts about the fear of crime and contribute to fear of crime literature.

Related variables and fear of crime

Sex is one of the most important parameters in the fear of crime, according to the literature. Most studies indicate that women have a much greater fear of crime than men (Britto, Stoddart and Ugwu, 2018; Callanan and Rosenberger, 2015; Macmillan, Nierobisz and Welsh, 2000; Yirmibesoglu and Ergun, 2015). The main reason for this disparity between females and males with respect to fear of crime concerns the sense of vulnerability to sexual assault for females (Chih-Ping, 2018; Ferraro, 1995; Pleggenkuhle and Schafer, 2018). Another reason for the higher level of fear of crime among women concerns gender roles. During the socialisation process, females are taught to be kind, polite, obedient, physically weak, and vulnerable. A patriarchal system in which females are reinforced for being passive encourages women to be both physically and socially vulnerable, thus increasing their fear of crime (Hunter, Krannich and Smith, 2002; Reid and Konrad, 2004; Schafer, Huebner and Bynum, 2006; Williams, Ghimire and Snedker, 2018).

Fear of crime is also related to living area because the physical characteristics of a living area, the socioeconomic status of occupants, security status, social support networks and so on affect individual perceptions of fear of crime (Siegel, 2012). Moreover, living area is related to the disorder model. Farrall, Jackson and Gray (2009) state that both physical and social disorder factors in living area increase level of fear of crime. Disorder is defined as an aspect of the social and physical environment that suggests to a resident the absence or weakness of common values, ideas and social controls in the living area. Consequently, disorder and the breakdown of social control in a living area increase residents’ fear of crime. Factors that illustrate disorder in a location include poor lighting, the presence of graffiti, vandalism, hiding places for criminals, poor state of buildings, disorderly public behaviour, areas adjoining vacant areas (e.g., car parks, parks or factories), noise pollution, dog litter, discarded needles, and empty or abandoned streets (Farrall, Jackson and Gray, 2009). Disorder factors may be categorised as either physical or social disorder factors. Physical disorder factors include garbage on the streets, graffiti, vandalism, abandoned buildings, and broken street lighting. Social disorder factors include public drinking, beggary, the presence of sex workers, noise pollution, and drug dealing. Such physical and social disorder factors can cause, or be the result of, a breakdown in social control and behavioural norms. Such disorder suggests to residents that local authorities are not interested in their wellbeing, thus causing them to lose trust in local authorities and to accept their living area as being disorganised and insecure. As a result, local residents’ fear of crime increases and they begin to shy away from public life (Karakus, McGarrell and Basibüyük, 2010).

Marital status is another variable in the fear of crime with a variable impact from one study to the next. Some researchers suggest that being single or unmarried increases one’s fear of crime (Braungart, Braungart and Hoyer, 1980; Will and McGrath, 1995). Other studies, however, report that being married increases one’s fear of crime (Alda, Bennett and Morabito, 2017; Mesch, 2010). The increased fear of crime amongst single or unmarried people might be attributed to attachment. Related studies show that fear is more salient among those who lack attachments to significant others. Also, Hanley and Ruppanner (2015) demonstrate that single, separated and divorced women are more likely to experience crime than married women. Divorced and widowed women, as well as those who have prior experiences of crime, are more likely to report feeling unsafe and fearful of crime. On the other hand, being married also increases the fear of crime because having a spouse and/or children results in additional responsibilities for the protection of loved ones. Married people worry not only about whether they themselves will be victimised, but whether their spouse and/or children will be victimised. This situation ultimately contributes to an increased fear of crime amongst married people (Boateng and Boateng, 2017).

Victimisation is often cited as one of the most important factors determining the fear of crime. Victimisation may be categorised as either direct and indirect. Direct victimisation means being the real victim of criminal action (Doran and Burgess, 2012; Goodey, 2005; Sakip, Abdullah and Salleh, 2018; Wolhuter, Olley and Denham, 2009). Indirect victimisation, however, recognises that people can experience victimisation vicariously. As such, one can experience the same emotions that result from direct victimisation simply by hearing about another’s experience of crime (Doran and Burgess, 2012; Kohm et al., 2012; Shoham, Knepper and Kett, 2010). Most studies of fear of crime assume a strong relationship between both direct and indirect victimisation and fear of crime (Fox, Nobles and Piquero, 2009; McNeely and Stutzenberger, 2013; Tseloni and Zarafonitou, 2008), while contradictory studies certainly exist (Curiel and Bishop, 2018; Farrall, Jackson and Gray, 2009).

Research questions

As indicated above, sex is perhaps the most critical parameter determining the fear of crime; as such, contemporary fear of crime research routinely takes into account differences in sex. Sociodemographic features, such as nationality and marital status, are also important determinants of fear of crime. Living area is also an important factor, given the relationship with disorder; as such, the current study considers disorder as a key parameter for observation. Similarly, as one of the most investigated issues in the fear of crime research, the current study will also investigate victimisation as a variable. Therefore, the current study focuses on three research questions:

1. How do sociodemographic factors (e.g., sex, nationality and marital status) relate to university students’ fear of crime?

2. How does living area relate to university students’ fear of crime?

3. How does direct and indirect victimisation relate to university students’ fear of crime?

Data collection and methodology

Data was collected from a sample of Turkish and Turkish Cypriot university students during European University of Lefke’s 2017-2018 autumn and spring semesters. Students were randomly selected from different faculties and departments among Turkish Cypriot and Turkish students. The surveys were conducted during lessons. Before the data collection, the researcher had permission from the Rector and instructors. The instructors were informed about the research and were asked to share about 15 to 20 minutes of their lessons. After the approval, the researcher went to classrooms and collected the data.

According to the university’s Registrar’s Office, the university enrolled 8,059 students from Turkey and 963 from Northern Cyprus, i.e., 9,022 students over this period. According to this population, the sample size was determined as 368, with a 95% confidence level and 5% sampling error. Because only Turkish Cypriot and Turkish students were included in the research, a stratified sample method was used. In this sense, at least 40 Turkish Cypriot students were needed for current research. The final sample included 330 students (n = 59 Turkish Cypriot; n = 271 Turkish). About 40 survey forms were excluded from the analysis because they were either incomplete or insufficient data had been provided.

The survey form, the Fear of Crime Scale (FCS), was developed by the researcher and was used in previous research (Köseoglu, 2017a). In that previous research, the reliability and validity of the FCS and its subscale about disorder were respectively determined as a = 0.91; a = 0.92 by using Cronbach Alpha test. In current research, Cronbach Alpha test was used again and the reliability was calculated for the first sub-dimension of the FCS (a = 0.92), for the second sub-dimension of the FCS (a = 0.80) and for the third sub-dimension of the FCS (a = 0.87). The FCS, therefore, was determined to possess a high level of reliability (a = 0.93). The disorder sub-scale also possessed a high level of reliability (a = 0.83).

The survey form consisted of three parts. The first part of the survey comprised questions and statements about student sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, sex, marital status, and victimisation experiences. In order to understand victimisation experiences, they were asked if they had been ever victimised, if so, when and which type of criminal activity they experienced. The second part of the survey enquired about students’ perceptions of disorder in their living area. Students were asked to rate their perceptions of disorder against a 5-point Likert scale with anchor statements ranging from 1 (Not a problem at all) to 5 (Very serious problem). There are statements about disorder, such as, “Substance abuse in my hometown”, “Property damages in my hometown”, and “Homeless, poor people in my hometown”. Higher scores reflect stronger perceptions of social and physical disorder. The third part of the survey instrument asked students to rate their fear of crime across various domains. As in the second part, students were asked to rate their fear of crime against a 5-point Likert scale, with anchors ranging from 1 (Not afraid at all) to 5 (Very afraid). Higher scores reflect a greater level of fear of crime. FCS has three sub-dimensions as fear of crime of offences against the person and property, fear of crime of immediate environment, and fear of crime after dark. There are questions for the first sub-dimension, such as, “How afraid are you of being physically assaulted?”, “How afraid are you of being sexually assaulted or being raped?”; there are questions for the second sub-dimension, such as, “How afraid are you of home attack?”, “How afraid are you of beggars nearby?”, and there are questions for the third sub-dimension, such as, “How afraid are you of walking around alone in the evenings?” and “How afraid are you when you are alone at home in the evenings?”.

Sociodemographic characteristics of sample

All students are aged 18-24, as such, age is not considered as a significant parameter in this study. 58.8% of the sample is female, leaving 41% as male. The majority of the sample (81.2%) is Turkish, while 17.8% is Turkish Cypriot. With respect to the education level of the sample, the majority of the sample (76.1%) is studying for their bachelor degrees. The majority of the sample who are from Cyprus live in Morphou (13%), and the majority of the Turkish sample live in the Mediterranean region (31.2%). Most of the students define their living area as urban (70.3%). Approximately 67.3% of the students describe themselves as single, while 31.2% identify as being in a relationship. Consequently, the sample is overwhelmingly unmarried (»99%).

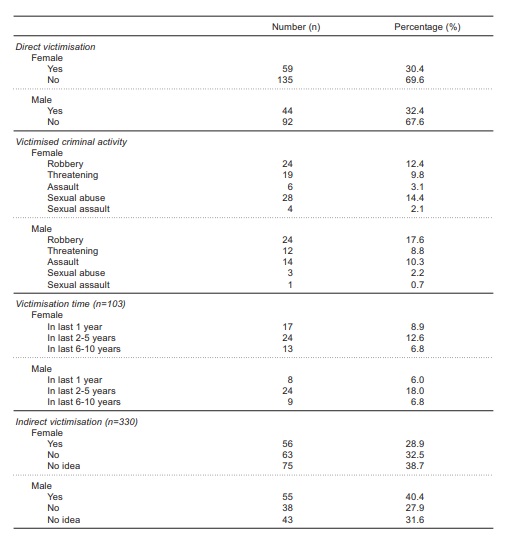

Participants’ direct and indirect victimisation experiences are classified by sex in table 1. For direct victimisation, the participants were asked to give answers as to when and how many times they were victimised and which type of criminal activity they experienced. The answers were not limited to only the campus or their living area. The aim of this question is to learn if they had been victimised in any period of their life. For indirect victimisation, the participants were asked whether their friends or relatives had been ever victimised.

Nearly 70% of both female and male students report that they had not been victimised directly. However, while only 29% of female students state that they had experienced indirect victimisation, 40.4% of male students report that they have experienced indirect victimisation.

Results

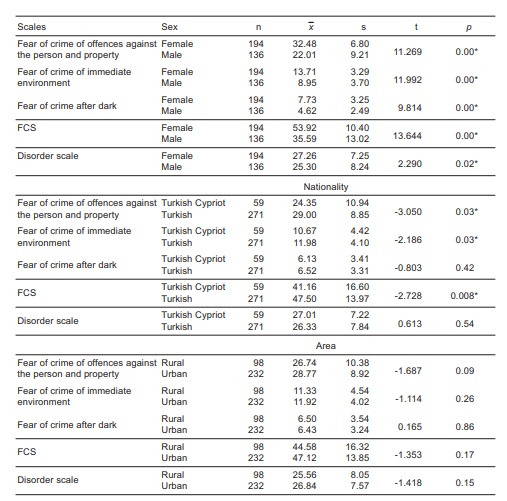

The results of an independent samples t-test analysis are displayed in table 2. According to the results, there are statistically significant differences between sex and all sub-dimensions of the FCS (p < 0.05). The scores for females on all FCS sub-dimensions are higher than those of male participants. Scores for the overall FCS are also remarkable. Female students provide higher scores than male students. This result supports the idea that women are more fearful of crime in general.

Another result shows a statistically significant difference between sex and the disorder scale (p < 0.05). Female students’ scores on the disorder scale are higher than those of male students. This may be explained by way of women’s perceptions of the disorder factors. Social and physical disorder factors, such as loitering, the presence of sex workers, drug/alcohol addiction, or high crime rates may be perceived by women to be more harmful than by men. This result also may be indicative of a link between a high perception of disorder factors and a high fear of crime level.

When nationality is evaluated, a statistically significant difference is found between the fear of crime of offences against the person and fear of crime against property (p < 0.05). These differences are most apparent amongst students from Turkey, whose scores on the first sub-dimension are higher than students from Northern Cyprus. Similarly, students’ fear of crime scores from fear of crime of immediate environment are higher amongst students from Turkey versus those from Northern Cyprus (p < 0.05). Also, there is a statistically significant difference between nationality and general fear of crime scores. General fear of crime scores are higher amongst Turkish students as compared to Turkish Cypriot students.

Living in an urban or rural area does not have an impact on level of fear of crime or disorder scales (p > 0.05). Some studies suggest that people living in urban areas have higher level of fear of crime as compared to residents of rural areas; this is especially true for intense disorder factors found in urban areas. However, no statistically significant difference is found in the current research.

In order to determine which tests would be used, the normal distribution of the total scores gathered from scales were analysed through a Kolmogrov-Smirnov test, Q-Q plot and Skewness-Kurtosis values. In these analyses, the dataset was not correlated with normal distribution, so a non-parametric test was used. Because of independent variables were only two, the Mann-Whitney U-Test was used for analysing direct victimisation and level of fear of crime. No statistically significant differences are found between two variables (Z = -0.854, p = 0.393). Similarly, no statistically significant differences are found between direct victimisation and disorder scale (Z = -1.379, p = 0.168). Indirect victimisation is also considered an important parameter in relation to the fear of crime; however, the current study finds no statistically significant difference according to an independent samples t-test (p > 0.05). Neither any statistically significant difference is found between indirect victimisation and the disorder scale (p > 0.05).

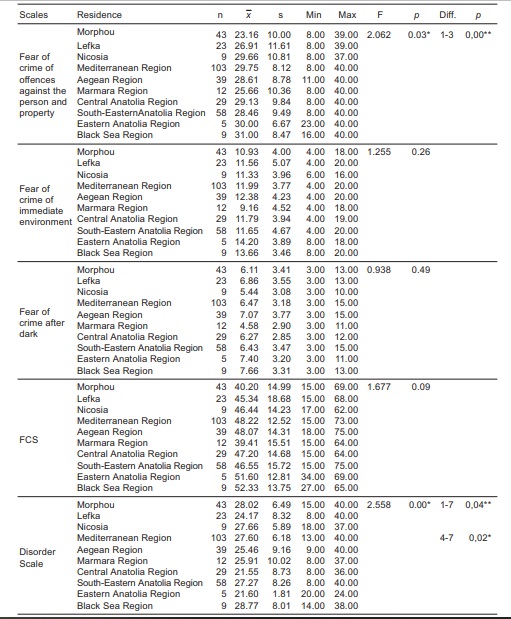

Anova was used to analyse living area, fear of crime and disorder scales and some significant differences were found. The differences were examined by using Post Hoc tests. For analysing the differences of fear of crime scale, the Tukey test was used because Levene’s test was found higher than 0.05. However, for the disorder scale, because Levene’s test was found to be lower than 0.05 level, the Games-Howell test was used, which is also one of the Post Hoc tests. As table 3 shows, there is a statistically significant difference between students’ living area and fear of crime for offences against the person and property (p < 0.05). These differences are clearest for Morphou and the Mediterranean area. While sub-dimension scores for students living in the Mediterranean area are higher than for other areas, scores for Morphou are the lowest. A statistically significant difference is found between participants’ living area and disorder scale (p < 0.05). This difference is caused by the higher scores of students living in the Turkish Mediterranean area, while the lowest scores are for students from the Central Anatolia areas of Turkey. In the Mediterranean area, the fear of crimes against the person and property is particularly high.

Table 3: Fear of crime and disorder by residence

*significant at the 5% level for Anova;

** significant at the 5% level for Post Hoc tests.

This study also includes marital status as a parameter. Because the dataset was not correlated with normal distribution, a non-parametric test was used. As the independent variables were more than two, the Kruskal Wallis test was used. According to Kruskal Wallis test analyses, there is a statistically significant difference between the fear of crime for offences against the person versus property based on marital status (p < 0.05). These differences are clear for single students, those in a relationship, and divorced students. While the scores are highest for those students who are single and in a relationship, they are lowest for divorced students. However, because there are only two divorced students in the sample, it is not possible to make any reliable statistical inferences. Similarly, there is a statistically significant difference between the general fear of crime and marital status (p < 0.05), with this difference attributed to students who are single, in a relationship, and divorced.

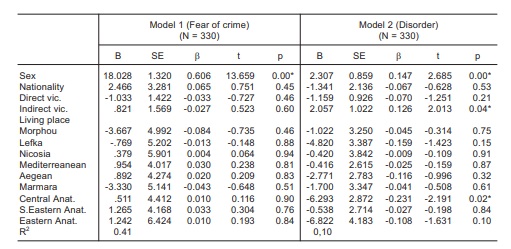

Table 4 shows the results of regression analysis. The first model is a test of the fear of crime model and includes the variables of sex, nationality, direct victimisation, indirect victimisation, and living place. Sex has positive and high level statistically significant impact on fear of crime (r = 0.61). We recall that the fear of crime model predicts that those who are female are more fearful of crime. Nationality, direct victimisation, indirect victimisation and living place are not statistically significant in the fear of crime model. However, those variables explain 41% of the variation in fear of crime (R2 = 0.41).

Table 4: Summary of multiple regression analysis for variables predicting students’ fear of crime

*significant at the 5% level.

The next model is the disorder model. Here, 10% of the variation was explained (R2 = 0.10). Again, sex was statistically significant but it has a negative impact (r = -0.021). Indirect victimisation also has a statistically positive and low significance impact on disorder model (r = 0.14). Also, one of the living places - Central Anatolia - has a statistically negative and low significance impact on disorder model (r = -0.001).

Discussion and conclusions

Fear of crime is a very important phenomenon because it constrains behaviour and lifestyles, increases anxiety, decreases social engagement, and increases the cost of criminal justice and security measures (Pleggenkuhle and Schafer, 2018). In terms of fear of crime among university students, it is important to observe the effects of fear of crime in relation to a predominantly young population.

The findings of the current research are largely consistent with those of prior research. Sex is clearly one of the most important parameters in influencing the fear of crime, as supported by this research. Fear of crime levels are considerably higher amongst female students as compared to male students and this finding is consistent with many previous studies (Britto, Stoddart and Ugwu, 2018; Callanan and Rosenberger, 2015; Macmillan, Nierobisz and Welsh, 2000; Yirmibesoglu and Ergun, 2015). There are numerous reasons for the higher level of fear of crime amongst female students; however, the most common explanation concerns a sense of vulnerability to sexual assault (Chih-Ping, 2018; Ferraro, 1995; Pleggenkuhle and Schafer, 2018). Likewise, the current study found that 87% of female students reported being fearful of being sexually assaulted. This result is remarkable and shows that female students from both Turkey and Northern Cyprus fear being considered open targets for sexual crimes. Another reason for this result may be explained by the patriarchal structure of both societies. In patriarchal systems, females are frequently regarded as sexual figures that should be ready for sexual activity whenever a male should wish. As such, some males believe that they have right to coerce females into sexual activities against their will. This imposition is transferred to both females and males via the childhood socialisation processes. While females are socialised to be obedient, males are socialised to define their power and masculinity through sexuality. Thus, females experience this heightened sense of vulnerability throughout all their lifetime, thus their fear of crime is often high especially in relation to sex crimes. This explanation may not be derived from the current results but it is the researcher’s observation which is supported by various researches (Cole, 2018; Rader, 2017; Skogan and Maxfield, 1980; Williams, Ghimire and Snedker, 2018). In these researches, female participants share the same belief that the fear of such sexual crimes are built and instilled in society, so these socialisation messages normalise fear of crime in the daily lives of women. On the other hand, it was found that male participants do not share the same worries. Therefore, women’s high fear of crime levels is one of the results of patriarchy and gender inequality.

Another important result is higher level of fear of crime among university students from Turkey. There is only one study about women’s fear of crime in Northern Cyprus (Köseoglu, 2017b); as such, no reliable comparison between Turkish and Turkish Cypriot students is possible. The researcher, however, would suggest that the fear of crime amongst Turkish students might be higher than Turkish Cypriot students because Turkey is a much larger, more heterogeneous and more chaotic country compared to Northern Cyprus. Also, Turkey has suffered a number of terrorist attacks since the 1990s, increasing social violence among Turks of different ethnic origins, with different ideologies and political tensions may make them much fearful than Turkish Cypriots, who live on a relatively small and peaceful island. Statistical data indicates that there are 89,725 sexual abuse cases reported in 2017 alone, 33,441 of the cases involved sexual abuse towards children in Turkey (General Directorate of Criminal Records and Statistics, 2017). Furthermore, the increasing rate of femicide cases in Turkey may stimulate a growing fear of crime. As of 15 March 2019, the platform called “femicides” listed on its website approximately 1,964 women who have been murdered over the last nine years. Moreover, 237, 294, 308, and 328 women have been killed by their husbands, boyfriends, ex-husbands, ex-boyfriends, fathers or brothers in 2013-2016, respectively. In 2017, 409 femicide cases were reported. These figures may help to elucidate the reasons for the higher level of fear of crime amongst Turkish, especially female students.

Some studies support the idea that living in urban areas contributes to the disorder factors responsible for the heightened fear of crime (Farrall, Jackson and Gray, 2009; Karakus, McGarrell and Basibüyük, 2010; Skogan, 1992). The current research finds no statistically significant difference between fear of crime and living in an urban area. However, when students’ living area and fear of crime were analysed, it is found that students living in Morphou, a small homogenous town in Northern Cyprus, had the lowest FCS scores, while students living in Turkey’s Mediterranean area had the highest. Similarly, scores on the disorder scale were the lowest in relation to Morphou, while highest in relation to Turkey’s Mediterranean area. This result shows that the places where the disorder factors are highest correspond with higher student fear of crime scores, thus paralleling many earlier studies (Abdullah et al., 2015; Adams, 2012; Austin, Furr and Spine, 2002; Chadee et al., 2017; Colquhoun, 2007; Swatt et al., 2013).

One much discussed issue in the fear of crime literature is victimisation. While previous studies show a link between fear of crime and victimisation (Doran and Burgess, 2012; Fox, Nobles and Piquero, 2009), more recent studies approach this issue with some suspicion (Farrall, Jackson and Gray, 2009; Karakus, McGarrell and Basibüyük, 2010; Köseoglu, 2017b). Furthermore, Xiong et al. (2017) found that, despite only 27% of university students reporting been victimised, the overwhelming majority (88.3%) indicate being somewhat afraid of being attacked, harassed, threatened, or verbally abused. Thus, having prior victimisation does not have a significant impact on the fear of crime as compared to non-victimisation. The current research also found that neither direct nor indirect victimisation had an impact on students’ fear of crime. This result may be explained by the number of students who had experienced direct versus indirect victimisation. Many studies report that recent direct victimisation has greater impact on the level of fear of crime (Britto, Stoddart and Ugwu, 2018; Fox, Nobles and Piquero, 2009). However, only 31% of the students sampled in this study stated that they had direct experience of victimisation, while only 7.7% of this group had experienced victimisation within the past year. In this context, there were simply too few students in this regard to make any effective impact on the results.

The current study is unique in its examination of the relative importance of fear of crime among university students in a Turkish and Turkish Cypriot context. The findings support the most important parameters of fear of crime (i.e., sex, disorder, and nationality). Also, the age group of the sample in this study is remarkable. Most studies support the premise that elderly people are more fearful than young people. In this study, the fear of crime was observed in a young university student population, finding a considerable degree of fear in relation to crime. However, replication of this study is necessary to distinguish the effects of the temporal situation in the Turkish Cypriot context.

As a researcher, some recommendations may be outlined in the light of current findings. In patriarchal societies, women are socialised to be more fearful; thus, gender-specific approaches to reduce the fear of crime or criminal victimisation among women are important in both Northern Cyprus and Turkey. In addition, in terms of social policy, gender study programmes should be added to the educational curriculum from the beginning of primary school in order to offset the negative effects of patriarchy and to improve the confidence of girls and women. Education programmes may also be offered in public institutions and workplaces to facilitate awareness raising. Furthermore, risky criminal areas must be determined cooperatively by the government, security forces, non-governmental organisations and universities, and some preventive studies about criminality must be organised.

Notwithstanding, there are several limitations to this study that could be improved in future research. The sample for this study consisted of Turkish and Turkish Cypriot university students at the European University of Lefka. Although this population is important in its own right, it limits the generalisability of the findings. Also, given the setting of this study, it was not possible to collect data from students of other nationalities. Future studies should take into consideration other students of ethnicities and conduct research in other universities in the Northern Cyprus.