Introduction

Gender violence is a serious violation of human rights and a public health problem that violates human dignity (Council of Europe, 2011) and translates into an extension of imbalances and discrimination that is reflected in all spheres of life (WHO, 2012), gaining a special dimension in the context of intimate relationships (Neves, 2016), having women as its main victims and men as its main perpetrators, although there is still scarce scientific knowledge and social invisibility surrounding men who are victims of domestic violence (Torres et al., 2018).

Domestic violence is a public crime in Portugal (article 152) with complaint being independent of the victim’s will, punishable from 1 to 5 years of imprisonment, aggravated to a maximum of 10 years under certain circumstances. Homicide or second degree murder (article 131) is punishable from 8 to 16 years of imprisonment, while aggravated homicide or first degree murder (article 132) is punishable from 12 to 25 years, the maximum prison sentence in Portugal. Aggravated homicide or first degree murder is considered when the death occurred in circumstances that reveal special blame or perversity, namely, the fact of having practiced the fact against their partners or former partners.

According to the Global Study on Homicide, 2019 (UNODC, 2019), 82% of the victims of homicide perpetrated by intimate partners were female, mostly in consequence of prior domestic violence. Considering the crime of homicide in Portugal, 89 cases occurred in 2019, of which 25.7% were committed within a marital or analogous relationship with the use of a white arm or a firearm (SSI, 2020). A percentage of 26.1% women were convicted of marital homicide in the same year (DGPJ, 2020). Also in 2019, the portuguese prisional population was constituted by 794 individuals condemend for homicide of which 70 were female (DGPJ, 2019) and 17 women were detained for intentional homicide in Portugal in 2018 (Pordata, 2020).

Several studies indicate that male marital homicidals are frequently motivated by jealousy, involuntary separation and fear of abandonment (e.g., Eriksson and Mazerolle, 2013), while female perpetrators tend to commit homicide acting as self-defense after suffering physical violence and death threats (Belknap et al., 2012; Felson and Messner, 1998; Weizmann-Henelius et al., 2012). Moreover, male marital homicidals seem to have more often than female, a prior criminal conduct, whilst female marital homicidals are more likely to have a background of abusive family and intimate relationships and help-seeking behavior (Campbell et al., 2007; Serran and Firestone, 2004; Swatt and He, 2006; Walker and Browne, 1985) and to commit homicide when male victims have threatened or abused children or other family members (Campbell et al., 2003). Also, male marital homicidals appear to premeditate homicide and to reveal attempting or commiting suicide more often than female (Velopulos et al., 2019; Weizmann-Henelius et al., 2003).

Though some authors defend that female marital homicidal may be protected by the stereotype of lessened responsibility (e.g., Auerhahn, 2007; Daly, 1989; Steffensmeier and Demuth, 2006; Vatnar, Friestad and Bjorkly, 2018), due to traditional conceptions of womanhood reinforced by positivist Criminology (Lombroso and Ferrero, 1996 [1895]), feminist criminologists advocate that they may be, instead, penalized for transgressing gender norms and criminal law (Fox, Levin and Quinet, 2019; Seal, 2010).

Globally, about 1 in 7 homicides (13.5%) occurs in contexts of intimacy, with the proportion of women killed by their partners being six times higher than the opposite and these deaths being the result of a health, social and criminal system that fails to identify and intervene in violence in intimacy and homicides (Stöckl et al., 2013). However, more than half of the women on death row are there for killing their partners or former partners, which is a much higher proportion than men who represent about 12% (Rapaport, 1996) and these statistics have been stable over time (Messing and Heeren, 2009; Streib, 2007). Another study demonstrated that when motives for killing contradict tradional gender roles and expectations, this has negatively influenced women’s sentences (Kim, Gerber and Kim, 2016). Similarly, an investigation showed that courts are not yet willing to recognize that their failure to protect victims of domestic violence results in the death of these women or of their aggressors, holding them accountable for their victimization and refusing their clemency requests (Jacobsen, Mizga and O’Orio, 2007). Still, evidence is mixed and some authors point out that more lenient penalties are applied to women who conform to more traditional gender roles (e.g., being married or having children) (Daly, 1989; Nagel, Cardascia and Ross, 1982), while harsher penalties, including death penalties (Streib, 1990), are applied to women who do not conform to the same stereotypes either because of their personal characteristics such as being economically independent, or because of practicing crimes associated with more aggressive and masculine behaviors (Messing and Heeren, 2009; Nagel, Cardascia, and Ross, 1982).

After living under a dictatorial regimen for 41 years, known as Estado Novo (Guimarães, 1986), Portugal still shows evidences of the influence of patriarchy and the Judaic-Christian religious ideology in the western world at a social, cultural and educational level that perpetuate symbolic violence against women and hegemonic masculinity (Leão, Neto and Whitaker, 2015; Scott, 1995).

According to Botelho and Gonçalves (2018), Portuguese judges are more likely to apply higher penalties when the victims of homicide are women, as well as when offenders use the right to remain silence and, a study on 237 sentencings concerning marital homicide (Agra et al., 2015), where 89.9% of victims were female and 90.9% of homicidal were male, concluded that among the 98 consummated homicides, 12 women were condemned. The average prison sentence was slighty lower to female homicidals, with a difference of 1.77 years for homicide or second degree murder and 0.77 years for aggravated homicide or first degree murder. Also, a recent study envolving 75 criminal homicides, 12 perpetrated by women against men and 63 by men against women, showed similarities considering abuse dynamics (Matias et al., 2020). Both had criminal records, substance abuse and psychiatric disorders, with crime occurring at home by the use of a white arm or a firearm and under the influence of drugs. Almost 80% of male homicidals were primary aggressors, and near 50% of female homicidals were victims of domestic violence. Prison sentences were three times higher for men, who were mainly convicted of first degree murder and women were predominantly convicted of second degree murder.

In order to develop a qualitative criminological analysis of the possible relationship between the practice of homicide by women against their partners or former partners and, if any, their previous exposure to a history of domestic violence, in-depth interviews were conducted, complemented with their individual files. Doing so, the specific goals of the present study were:

1. Analyze the sociodemographic, legal and criminal characteristics of the inmates convicted of the murder of their partners or former partners, through documentary analysis of their individual files and in-depth interviews, focusing on the characterization of their marital homicides, crime dynamics, previous history of domestic violence, defense and sentences.

2. If any, understand the relationship between the practice of homicide and a history of domestic violence, premeditation, modus operandi, existence of accomplices, existence of a previous criminal record, committing other crimes simultaneously and its influence on the legal framework and dosimetry of their sentences.

Method

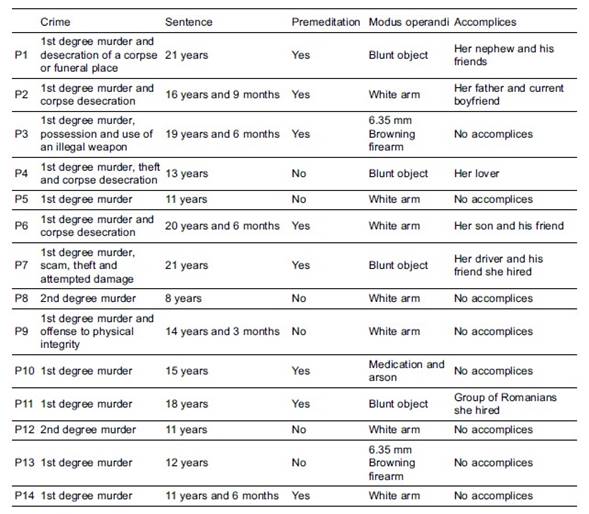

This study was developed in the three main Portuguese female prisons where the largest universe of female homicidal are detained for murdering their partners or former partners. After being authorized by the Directorate-General for Reinsertion and Prison Services (DGRSP), the first part of data collection consisted in analyzing the individual files of all women who fulfill the inclusion criteria defined by the research team: (1) have committed homicide against partners or former partners, and (2) have been sentenced to effective penalties. Thus, the Directorate-General of Social Reintegration and Prison Services provided, at the time of data collection, in 2019, 16 cases based on our inclusion criteria. Of this sample, 2 women refused to participate in the study, so we worked with a sample of 14 women. Their files were analyzed through document analysis, using a registration grid in order to find, select, appraise and synthetize data (Labuschagne, 2003; Bowen, 2009) contained in their individual files. Document analysis is a process that combines elements of content and thematic analysis, where the researcher should distinguish the pertinent information to a phenomenon and recognize patterns within the data for cathegories of analyzis to emerge (Corbin and Strauss, 2008; Fereday and Muir-Cochrane, 2006), in this case, socio-demographic and criminal factors, and motives for committing homicide. By using another source apart from documents to complement and gathered information, namely in-depth interviews, this triangulation helps the researcher to ensure that there is no bias in our findings and establish credibility (Bowen, 2009; Patton, 1990; Yin, 1994).

All the ethical procedures were respected, especially those concerned with confidentiality and human care (APA, 2017) during in-depth interviews, which were audio recorded and took place in private offices located in prison wards, after participants had signed informed consents.

After fully transcribing all interviews, in order to assist this qualitative analysis and avoid human error, we used NVivo software (version 11) in the sense of a more effective and accurate analysis (Zamawe, 2015), since it allows to import the transcripts into the software and code the documents easily through coding stripes and memos, connecting them in between, assuring or not the researcher’s perceptions of the data (Welsh, 2002). Although qualitative research and data analysis are carried out thoroughly, the use of software in qualitative research is believed to add rigour to the analysis, namely by searching data electronically and having a general sense of the collected information (Richards and Richards, 1991; Welsh, 2002).

Then, a thematic content analysis was carried out to explore central themes (Bardin, 2011), searching and identifying topics that were common to all interviews (DeSantis and Noel Ugarriza, 2000). The final codification was achieved by consensus of the research team, after familiarizing with data, generating initial codes, searching for themes and reviewing them, defining and naming themes, organizing and, finally, producing a report (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Nowell et al., 2017; Vaismoradi, Turunen and Bondas, 2013) as described in the results section through excerpts of the interviews that will be presented to illustrate the themes.

Thematic analysis is a qualitative descriptive approach that constitutes a useful tool to provide rich and detailed account of data (Braun and Clarke, 2006), sharing the same aim of content analysis by examining narratives from life stories and breaking the text into excerpts and treat it descriptively (Vaismoradi, Turunen and Bondas, 2013). Thematic analysis can produce trustworthy and insightful findings when rigorously applied as it summarizes key features of large data, forcing the researcher to take a organized approach while handling data, producing a clear final report (Braun and Clarke, 2006; King, 2004; Nowell et al., 2017). The trustworthiness of this qualitative method can be guaranteed by its criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Elo et al., 2014; Lincoln and Guba, 1985; Nowell et al., 2017).

In order to facilitate the reading, making it more structured and organized, the results will be presented using the total number of participants, two tables relating to their sociodemographic as well as legal and criminal characterization of the committed crimes, and the excerpts that illustrate their narratives collected during in-depth interviews.

Results

This section will focus on the description of the results collected through the analysis of the inmate’s in-depth interviews transcriptions and also the analysis of their individual files.First, we characterize marital homicides through the analysis of their motives, dynamics and previous history of domestic violence. Then, we examine the courts’ decisions, legal framework and dosimetry of their senteces and the relationship between variables such as history of domestic violence, premeditation, modus operandi, existence of accomplices, existence of a previous criminal record and committment of other crimes simultaneously.

Characterization of marital homicides

According to their individual files and in-depth interviews analysis, regarding their relationships with the victims, 12 of the participants committed the crime against their current partners at the time, while 2 of the participants committed the crime against their former partners. During the interviews, the participants argued distinct motives for killing their partners or former partners, depending of particular circunstances, both personal, interpersonal and situational. Episodes of violence between the couple stand out in half of the situations as seen on the demonstrative excerpts below, although this does not always coincide with what is indicated in their individual processes, as we can see in the first excerpt where participant P14 reports having been a victim of domestic violence by her partner, but her individual file indicates that the motivation for the practice of homicide was related not only to domestic violence, but also with jealousy and revenge on the part of the inmate. In the excerpt related to participant P13, the motivation pointed in her individual file refer to the fact that she and her husband were already separated, but still shared the same house and for that reason the former couple experienced several disagreements and disorders:

On that day, as every human being has its limit, I think that day I reached mine. That day I don’t know what could have happened, I think he was really possessed, he left the house and came back and it seemed that I was his target! That day, I couldn’t tell him anything, he came home three times and hit me those three times. The last time, he hit me with a bottle on my head and I had to be assisted in the hospital. When I went home, he was there and as soon as he saw me, he said: “Get out of here, otherwise I’ll kill you!” and then I took my phone out of my purse and I felt the knife inside it and when he came to hit me… I had an impulse, I didn’t want to kill him, it was just meant to scare him, to prevent him from hitting me! But now, I’ve been here for two years now and that was two and a half years ago, and even today I don’t remember much… I only really knew that he died around an hour after. I was in the police station and I knew I had done something, but I had no idea that he had lost his life! I thought he was only hurt! I went into shock! [P14]

We were together for about ten years and I went to my mother’s because I couldn’t take it anymore. He went there with a gun pointed at me, but as I had my son in my lap he said: “I will not kill you because you have the kid in your lap!” The other day I went to the police, they took the shotgun from him, but the next day they gave it to him again! And then, more than twenty years later, more than twenty… Things got worse and worse. [P13]

Their individual files state that in two situations, the motives for committing the crime were related to financial reasons such as the husband of participant P11 being financially dependent on her and spending her money and, in the case of participant P7, the reasons were related to her intention to seize her husband’s assets, values and benefit from an insurance premium in order to maintain the high standard of living to which she was accustomed to. Also according to the individual files of participants P1, P4, P6 and P10, there are other motivations such as the existence of an extramarital relationship by the defendant and non-acceptance of the end of the relationship and new romantic relationship of participant P2. The interview excerpts described below coincide with the data found in the individual files.

I was the one who supported the family and he forced me to give him all my money! Since he didn’t want to make a life with me, he didn’t want to sleep with me, he treated me so badly… So instead of giving him the money, I started to save it for myself and to build that house I wanted! [P11]

That day my ex saw a strange car that was my boyfriend’s car! He waited for us to wake up in the morning, I woke up to many calls on my phone! Then I called the police at six thirty in the morning but the police didn’t show up on time. They only showed up at my house at eight! He said he wouldn’t leave because he was going to kill me, our son and my boyfriend! [P2]

Crime dynamics

Although data on the individual files of the participants P1, P2, P3, P6, P7, P10, P11 and P14 suggested the existance of premeditation on eight of the situations, most of these women state in their interviews that they acted impulsively to justify their conduct.

I did not premeditate his murder because if I wanted to kill him I would not do it in front of everyone! You wouldn’t want to leave witnesses, would you? There are no perfect crimes, but I wasn’t going to do it in front of other people. The judge and the prosecutor wanted to decree that it was premeditated, but in the Supreme Court, the judges said that there was no reason to be premeditated. [P14]

Regarding the modus operandi referred to in their individual files, the use of white arms was the most common, occurring in seven of the situations, being characterized by the use of kitchen knives to deliver several blows (e.g., 6.69 in, 5.70 in, 4.33 in and 3.93 in - blade lenght). Four women also resorted to blunt objects such as a wooden handle about 39.3 in long, a 34.6 in long and 10 lb heavy sledgehammer or, used their own hands to deliver punches and blows to the victims’ head and torso, as well as through asphyxiation by using a plastic bag tied with an electrical cord around the victim’s head. In two of these cases, these women fired shots at their partners or former partners using 6.35 mm Browning semi-automatic pistols. In one another case, the inmate resorted to the use of Clozapine pills and arson. Six of these women were also convicted of other crimes, namely one for the possession and use of an illegal weapon, one for the offense of physical integrity, another one for theft and, simultaneously, concealment or desecration of a corpse or a funeral place, and four for desecration of a corpse or a funeral place.

I set fire. It started to burn. I locked the door, locked the front gate and I went to a dam about 20 or 30 km away to throw the bottle of alcohol, the gloves and all that. But before I committed the crime, I was already taking antidepressants and I took four antidepressants that day. Then when I came home again, I didn’t see smoke, I didn’t see fire, I didn’t see anything, I stayed in my van, walked around and around. I called the fire department to say there was a house on fire and gave the address. [P10]

The individual files demonstrate that two women were drunk at the time of the crime (e.g., 0.98 g/l rate) and two have asked for immediate assistance. For the commitment of the crime, six women had help from accomplices, namely counting on the support of the fathers, boyfriends, employees, nephews, sons and/or by hiring other people to commit the crime or to assist them. Four women desecrated the body or funeral place and one hid the body. It should be noted that in 4 of the 14 cases, these women did not participate directly in the murder. The informations found in their individual files coincide with what was reported in the interviews.

Previous history of domestic violence

According to the analysis of the individual files, in six of the cases domestic violence was considered to be unproven in court, although there were allegedly witnesses. In one of the situations, it was proven that there was no domestic violence between the couple and, in four of the cases, there are no records about this topic on individual files. The existence of a history of domestic violence between the couple was proven in court only in the cases of participants P2, P12 and P14, despite the fact that all participants reported having suffered domestic violence by their partners in their narratives.

According to participants’ interviews, family and intimate partner violence took part of their lives prior to commiting homicide, being these known risk factors for the practice of this type of crime (Campbell et al., 2007; Serran and Firestone, 2004; Swatt and He, 2006; Walker and Browne, 1985).

I was never happy in relationships. Never. I don’t know if this is genetic… It’s not genetic, but it happens, it happened to me! I married at 22 years old and already was a victim of domestic violence. [P12]

I had my ear completely destroyed! Now I have a complete internal hearing aid for my ear (takes a deep breath). From the moment he knew I was pregnant, he got worse! […] So he cut me off, I couldn’t leave the house, I couldn’t talk to anyone, my phone could only have his number, my mother’s and my father’s! [P2]

How many times have I had a pistol pointed at my head… How many times… [cries]. How many times has my girl seen that! He left me with this whole eye swollen [exemplifies], he pulled this skin all over my nose, left me here with my face all ruined and I walked for years with red things on my face, I don’t even know if I still have it… From his nails! He grabbed my neck and made me all black and blue, and my daughter heard the noise of what he was doing to me, got up to see if she could stop her father, but he had a strength that does not cross anyone’s mind! He grabbed her and chew the whole child! Even the little girl’s hand he put in his mouth and chewed it all! [P13]

Defense and sentences

Two of the inmates benefited from a public legal defense and, the same percentage, benefited from private legal support. Also according to their individual files, two appealed their initial sentences. No other information of this nature could be found in the remaining files. In general, the participants had little knowledge about legal procedures and considered that their defenses were ineffective, as we can see by reading the following excerpts of their interviews.

I thought that for all that I went through and all that I’ve told my lawyer, that the judge was not going to convict me! I told the lawyer everything and he said: “Be quiet and don’t talk!”. I thought the judge was going to read my head and heart! I don’t know, I was psychologically ill, I was not ok! [P7]

I got sentenced to ten years and five months. We were accused of first degree murder, but considering his background, everything was taken under consideration and it was a female judge… It made a lot of difference! […] When she goes from first degree murder to second degree murder… Her words will stay with me… May God help her a lot! She said that we acted out of fear, for everything that had already happened, for what he was! She seemed to be feeling what I felt: “They did this because they had enough! The father did this for his daughter because he couldn’t see her like that!” […] But then the public prosecutor appeals. A man. He didn’t like me [laughs]. I will never forget his words again: “I ask for nineteen years for everyone! For everyone! Why? I am convinced that she did not participate in the act, but for me they’re all guilty! [P2]

According to the analysis of their individual files which was coincident with what was found in their narratives, ten participants of the sample were convicted of first degree murder and four of second degree murder, being sentenced, on average, to 15 years in prison, varying between 8 and 21 years. Nine participants of the sample premeditated the crime, planning their crimes by purchasing firearms, bladed weapons or medication for the purpose, hiring other people in exchange of large amounts of money (e.g., 168 000Euro), demonstrating, according to the judges, “intention to kill” and, a “process of formation of the will to commit the crime, which should be associated to situations in which there is calm, reflection or cold blood in the preparation of the crime, insensitivity, indifference and persistence in execution”. In 9 of the 14 cases, the judges considered that the defendants premeditated their acts and that they acted “in a deliberate, free and conscious manner, knowing the illegality of their conduct and not fulfilling their duty to protect, support and treat your husband with affection”, and, therefore, aggravating their sentences accordingly. The average sentence of prisioners who premeditated the crime was 17.96 years, 36% higher than those who did not premeditated their actions.

The average sentence for women whose modus operandi involved the use of white arms was 13.34 years, 13% lower than the global average sentences (15 years of imprisonment), whilst the average sentence for women who used blunt objects was 12% higher than the average sentence.

The average sentence for women who had accomplices was 18.41 years, 31% higher than those who did not had any help. Regarding those who participated directly in the crime, their average sentences were around 13.65 years, 29% lower than those who premeditated their crimes by asking accomplices for help and, therefore, aggravating their sentences. The average sentence for women who were convicted simultaneously of other crime was 17.56 years, which was 24% higher than those who did not commit other crimes.

Five participants already had a previous criminal record for committing crimes such as fraud, theft, attempted damage, driving without legal clearance, document forgery, illegitimate appropriation in case of accession or found thing, driving a vehicle under the influence and irregular residence in Portugal. The average sentence of prisoners who had a criminal record was 15.12 years, compared to 15.20 years in primary offenders, something that did not influence them positively or negatively. Also as stated in their files, participants P4 and P9 had mental illnesses such as histrionic and paranoid personality, difficulties in communicating and adapting to social situations and use of manipulative strategies, but were not considered mentally unfit. Although there was no reference to this issue in her file, during the interview it was referred by the prison guards and verified by the researchers that participant P5 suffered from a mental disorder that compromised her ability to understand and comprehend social situations, being medicated and psychologically monitored for this reason in prison.

The average sentence of prisoners whose history of domestic violence was proven in court was 13.16 years which was 17% lower than those whose history of domestic violence did not exist or was not proven in court.

Discussion

In general, while answering goal 1 of this investigation, we found that in this sample of 14 participants, the information recorded in their individual files not always matched (e.g., previous history of domestic violence, motive for committing the crime) or was absent comparing to the information provided during their interviews (e.g., public or private legal support, presence of a mental health disorder).

With regard to reports for domestic violence, these women often pointed in their interviews that they asked for help but did not obtain the support they needed from the authorities (e.g., police returned firearms to their partners or former partners; close relationship between police elements and their partners or former partners; lenghty legal processes). In their narratives and also in their individual files, we were able to find several aspects that are described as risk factors for the occurrence of domestic violence and homicide, such as violence in family or intimate contexts, alcohol and/or other substance abuse, death threats, low socioeconomic status and access to firearms (Aldridge and Browne, 2003; Campbell, 2004; Dobash et al., 2004; Gartner, Dawson and Crawford, 2001). According to the participants’ reports it is possible to find these risk factors in all the analyzed cases, which is why an early and specialized intervention could have prevented such outcomes. Nevertheless, most participants reveal significant insight into their actions by condemning them.

Even though the motives for committing their crimes were varied, the inmates reported in their interviews that the reiterated domestic violence history between the couple or former couple stands out from all other motives for committing these homicides. Through our analysis it was possible to verify that the average sentences for prisoners whose histories of domestic violence were considered proven in court were 17% less severe than others, which shows that this factor does influence positively the dosimetry of their sentences in response to goal 2 of this study. According to Pais (2010), for some female victims of domestic violence, the homicide of their partners or former partners frequently occurs in moments of specially vulnerable and emotional states after episodes of verbal and/or physical violence, which is why it is also important to understand the impact of their domestic violence histories in a intimacy context by analyzing the emotional state under which the crimes were committed and how this emotional state may or may not have compromised their decision-making capacity, consequently, resulting in less criminal responsibility, but not making them less accountable for their actions (Casal, 2004; Dias, 1999).

As stated by the proven facts in their trials, eight participants of the sample premeditated the crime, planning their crimes by acquiring the necessary means to commit them (e.g., firearms) and showing an “intention to kill”. According to the purpose of goal 2, it was also possible to verify that the average sentence of the prisoners who did not premeditated their crimes was 36% less severe than those who forethought their actions.

Finally, we found that 12 of the 14 participants were convicted of first degree murder, serving sentences that reach 21 years, almost completing the Portuguese legal cumulus of 25 years in jail, causing them to feel dissatisfied with their defenses, whether they had a private or public attorney. Regarding the judges convictions, some of the participants highlight the fact that they had less serious sentences due to the proven victimization suffered by their partners or former partners, influencing the dosimetry and legal framework of their sentences by reducing them as the analysis shows (e.g., second degree murder), while others highlight the special severity of their convictions and its legal framework (e.g., first degree murder) which made them fearful of the way they are perceived socially, inside and outside the prison environment, for being considered doubly transgressive since they have deviated not only from criminal legality but also from the gender role that they are expected to fulfill socially (Lombroso and Ferrero, 1996 [1895]; Matos, 2008). Notwithstanding, international literature shows mixed evidence regarding this issue not allowing us to confirm that such discrimination does in fact occur (Daly, 1989; Nagel, Cardascia and Ross, 1982; Streib, 1990).

Conclusion

The main factors that influenced the dosimetry of these women’s sentences by reducing them were no premeditation of their actions, direct participation when comitting the homicide, no help from accomplices, use of white arms, not comitting other crimes simultaneously (e.g., concealment or desecration of a corpse or a funeral place; possession and use of an illegal weapon), and also, the existence of a previous history of domestic violence which shows that previous contexts are considered, showing leniency while assigning their sentences.

Although the motives for commiting their crimes were varied, all of these 14 women claim to have experienced life trajectories which were repeatedly marked by abuse, either by their partners or former partners or in a family context during childhood, causing undeniable impacts on their structure as people. The participants are serving sentences with an average lenght of 15 years, in a Portuguese legal cumulus of 25 years for the commitment of first degree murder, which some participants feel it’s reasonable for their actions and others feel especially unfair and penalized, although it was possible to verify that a proven history of domestic violence does reduce the dosimetry of their sentences, proving that the court considers previous contexts.

Therefore it is important to standardize and consolidate the existing information in all individual files and to emphasize the authorities role when preventing and intervening with domestic violence victims, valuing their narratives, proteting not only the victim’s life but also their abusers. Finally, it is crucial that we continue to invest in policies that emphasize the importance of gender equality and equity, providing victims with greater independence and resources that enable them a safe exit from an abusive relationship.