Introduction

Early marriage is a human rights violation and a harmful practice that unreasonably affects girls around the globe, preventing them from living their lives free from all forms of violence. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, early marriage is defined as any marriage where at least one of the parties is under 18 years of age (Durgut and Kisa, 2018). Early marriage violates several human rights, including the right to education and employment, freedom from violence, freedom of movement, the right to consensual marriage, reproductive rights, and the right to reproductive and sexual health care. Early marriage also makes girls more vulnerable to violence, discrimination and abuse, and prevents them from fully participating in the economic, political and social spheres.

The trend of early marriage in developing countries varies from a high of 70.0% in South Asia to a low of 30.0% in Southeast Asia. According to UNICEF (www.unicef.org/indonesia, 2020), of all the ASEAN member countries, Indonesia is the second-highest ranked country in terms of child marriage. In 2018, of the total population of 627 million, 11.2% of Indonesian women were married at the ages of 20-24 years. Meanwhile, 4.8% women were married when they were younger than 17 years of age. Child marriage below 16 years constituted 1.8%, while below 15 years it was 0.6%. In sum, one in nine girls younger than 18 years married early. Cases of marriage at early ages in Indonesia have long been a concern to multiple parties due to their worrisome sizes and impacts. Nationally, the rate of early marriage stands at 25.7%, meaning that of every 100 marriages, 25 involve minors (Arimurti and Nurmala, 2017). The Statistics Indonesia’s data show that the rate of early marriage in 2018 increased to 15.6% from 14.2% over the previous year. The provinces with the highest percentages of early marriages are South Kalimantan (22.8%), West Java (20.9%), and East Java (20.7%) (Arimurti and Nurmala, 2017).

In the province of East Java, child marriage primarily occur in the Horseshoe region (Tapal Kuda), including Pasuruan, Probolinggo, Bondowoso, Situbondo, and Madura island, most of whose communities are of the Madurese ethnic group. In this region, the percentage of early marriages reaches around 20.15% of all marriages that occur in East Java province (Arimurti and Nurmala, 2017). Early marriage is a art of the culture in the Horseshoe region, where marrying at na early age, especially for girls, is considered legal by religion (Islam) and socioculturally acceptable to prevent spinsterhood (Pohan, 2017). Parents’ fear about their daughters’ futures, which, in addition to economic reasons, is used to justify marrying their daughters. Early. The prevalence of early marriage is a concern and must be appropriately addressed to prevent girls’ becoming victims of early marriage.

Numerous studies have proved that the effects of early marriage are not only associated with girls’ lack of emotional preparedness for the hardship of married life, but are also related to its blocking of their career opportunities and restriction of their ability to develop their future economic potential (Suyanto, 2013; Desiyanti, 2015; Nguyen and Wodon, 2015; Durgut and Kisa, 2018). Instead, of developing their socioeconomic potential, marriage, pregnancy, child-rearing, and domestic chores all forced girls who marry early to abandon their dreams (Williamson, 2014).

Child marriage not only wrenches girls from their basic rights to study, develop, and become children to the fullest, it also potentially paves a way to various acts of violence (Boyce et al., 2018). As a result of emotional unpreparedness, many girls divorce during the first year of the marriage (Strat, Dubertret and Foll, 2017). Girls who are married early often face barriers to school education and are much more likely to experience domestic violence, harassment, and even marital rape (Pearson and Speizer, 2011).

At the end of 2018, the Indonesian Constitutional Court approved changes to the marriagable age provisions (Beritagar.id, December 13, 2018). Furthermore, the Indonesian House of Representatives (DPR) and the Indonesian government agreed to revise article 7 of Law Number 1 of 1974 on Marriage. The minimum age for girls to marry increased from 16 years to 19 years. This limit also applies to boys. The decision to increase the minimum age at which girls and boys are allowed to marry is expected to create a golden generation, which will enhance the country’s national development goals (Tajuk Rencana Kompas, September 23, 2019).

This decision to increase the minimum age to marry for girls is expected to reduce the risk of mother and child mortality, and to prevent early marriage from ending up in separations. However, the extent to which changes to the legal umbrella may have successfully slowed down the rate of early marriage in Indonesia still needs to undergo the test of time.

Against this backdrop, this article examines the causes and impacts of early marriage in the Horseshoe region (Tapal Kuda) of the eastern part of Java island, where early marriages are more common compared with other regencies and cities in Indonesia. This article deals with the root causes of early marriage, the life circumstances of girls in child marriages, and the impacts of early marriage on girls. This study corroborated previous findings regarding the phenomenon of early marriage in Indonesia. Through the use of triangulation with quantitative and qualitative data, this study adds to existing research and presents deeper and more nuanced accounts of the phenomenon of early marriage in Indonesia. It also formulates contextual recommendations to rescue and protect girls from becoming victims of early marriage.

Literature review

Early marriage usually occurs among girls from underprivileged families. Due to economic pressures, poor parents’ transfer the burden of responsibility for the daughters to others (sons-in-law and their families). High numbers of children and insufficient daily earnings to cover basic needs often encourage parents to marry off their daughters, who they do not consider as productive laborers. Unlike sons, who are regarded as assets and sources of income, sooner or later, daughters are to be claimed by others; hence, the sooner the daughters are released, the better it is considered. Otoo-Oyortey and Pobi (2003) found that in poor countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, an estimated 60% of poor girls were married when they were under the age of 19 years, despite the fact that early marriage tends to perpetuate the feminization of poverty (Suyanto, 2012, 2013). Frequently, for reasons of culture and religion, girls are married off by their parents (Desiyanti, 2015).

Many girls in developing countries have little or no choice over the age at which they enter into marriage and who they marry. Girls who are married early tend to have less education, start child care earlier, and are less involved in domestic decision-making. It is even more concerning that girls who are married early are also more likely to be victims of domestic violence (Jensen and Thornton, 2003). In Mexico, Boyce et al. (2018) found that girls younger than 16 years of age are vulnerable to forced early marriage, pregnancy, and sexual violence. Unlike romantic stories that tell about a couple who love each other, in reality, child brides are faced with a wide range of problems that are very harmful. Their rights as wives are underappreciated, and many early marriages are followed by polygamy in which girls or women are powerless to refuse.

Durgut and Kisa’s findings (2018) revealed that in Turkey, children who were involved in early marriage generally faced difficulties and problems during their marital adjustment periods. Of the 246 girls married younger than 18 years, some were likely to suffer from incidents of physical violence, which were conversely correlated with marital adjustment. The more frequently a girl suffered from physical violence, the slower she was in adjusting to her married life. As a result of subcultural incompatibility and conflicts between a couple, many girls are victims of acts of violence by their spouses. They are compelled to adapt to the lifestyles and habits of their spouses’ families, which is not easy for them. At a point where incompatibility and inability to adapt culminate, conflicts ensue. The loss from such conflict usually falls on the girls (Mubasyaroh, 2016).

Girls who are forced into marriage at early ages usually drop out of school (Sakellariou, 2013; Williamson, 2014). The opportunity to reach higher education levels vanishes, especially once they have children. Child care responsibilities and household chores contribute to blocked educational opportunities. The ideal is that girls take advantage of the opportunities to pursue education. In many countries, scholarships are offered for girls to pursue education, at least at the primary education level. However, due to sociocultural norms and pragmatic considerations such as those found in this research, options are not always readily available for girls. Restrained within the families, probably even coupled with parental abuse, underage girls are often pushed out of their old lives into new ones with their spouses. Those who are fortunate may achieve better lives. But for those less fortunate, they frequently fall into the trap of violence at the hand of their spouses and their spouses’ families.

Research method

This study used mixed quantitative and qualitative research methods. A total of 300 respondents were surveyed and 30 of them were interviewed. This study was conducted in three regencies with the highest rates of early marriage in East Java province, namely, Bondowoso, Situbondo, and Probolinggo regencies. In these three regencies, it is the norm for girls to be married after graduating from junior high school or even elementary school, especially in rural areas. The inclusion criteria for respondents in this study were: (1) being married girls, (2) aged below 18 years when starting marriage, and (3) residing in the research locations.

The recruitment of respondents in this study was carried out in two ways. First, they were recruited based on the data on early marriage recorded by the Office of Religious Affairs (KUA) in the three research locations. Based on this data, the researchers then contacted the prospective respondents. Second, because not all the cases of early marriage were officially registered in the KUA, the researchers also conducted the recruitment process based on information from the respondents who had agreed to be involved in this study. Through this snowball technique, the researchers then contacted the potential respondents. Of the total 300 respondents, 30 respondents were recruited in this way. All respondents gave consent to be involved in this research and their identities remain anonymous.

The process of collecting quantitative data was carried out by distributing questionnaires to the selected 300 respondents in Bondowoso, Situbondo, and Probolinggo Regencies (100 respondents for each regency). The survey data was then sorted based on the question topics relevant to the research problems. The survey was aimed at reaching an overview of the respondents’ backgrounds and also to obtain data on the factors that influence early marriage, the respondents’ and their families’ roles in the process of early marriage, the impacts of early marriage, and the socioeconomic risks that they faced.

The girls were mostly (72.7%) first married at the ages of 17-18 years, and others (26.3%) married when they were aged 15-16 years. Another 1% of the respondents stated that they entered marriage at the ages of 13-14 years. All of the respondents in this study were still married and had been married for one to three years. However, not all the respondents were officially married and had their marriages registered at the KUA. Of the 300 respondents researched, only 73.3% stated that they were officially married at the KUA; the other 26.3% were engaged in nikah siri, or marriages which are religiously acknowledged, but unregistered at the KUA. Among the societies in the Horseshoe region, the tradition of nikah siri is valid and powerful. To some of them, the most important thing is that the children do not fall into zina (adultery) practices.

Most of the respondents (47.0%) completed a senior high school level of education, 41.0% completed junior high school and 11.7% completed elementary school. However, many pursued education only up to the elementary school level. As many as 41.0% of the respondents stated that they had only completed junior high school education when they entered into the married life, and 11.7% only graduated from elementary school and then discontinued their education due to marriage. Only one respondent started marriage after graduating from university.

In order to deepen our understanding of the girls’expereinces, 30 in-depth interviews were conducted. These qualitative informants were taken from the same three locations, each with 10 informants randomly selected and interviewed based on the research problem of this study. In-depth interviews were conducted in several places - at each informant’s house, the informant’s office, the informant’s parents’ house, and in mutually agreed upon local restaurants. The questions asked in this interview were intended to sharpen the quantitative data that had been obtained. The interview questions focused on the background of the informants’ early marriage and their experiences of early marriage. Twenty interview questions were asked of each informant and every interview session lasted between one hour and three hours. All primary data collected were verified and further processed. In this study, primary data was collected through direct interviews conducted face to face. All respondents answered all questions posed by the researcher. The primary data that has been collected is then verified. The purpose of data verification is that the researcher checks the completeness of the data from each respondent before entering the data into SPSS v.21. The data from this activity is processed and displayed in a concise form, namely a table with the hope that it will be easier for readers to understand and clarify the analysis.

These data are certainly not presented plainly in the form of interview transcripts. They are processed and organized in the form of concise tables to make it easy for readers to understand and to make the analysis clear. The quantitative data analysis was descriptive. Data analysis was carried out based on the survey question points related to the major themes of the factors that influence the practice of early marriage. The results of the survey were then used to explain the facts of early marriage, the factors that influence the decision to enter into early marriage, and the impact of the practice of early marriage. Meanwhile, the qualitative data analysis was carried out by sorting out the results of the in-depth interviews according to the themes relevant to the research questions. Furthermore, these themes were linked with the survey data and interpreted to sharpen the explanations about the explanatory factors and impacts of early marriage among girls in Indonesia. Finally, data triangulation was carried out on primary data to cross-check data between the answers given by women involved in early marriage by asking questions of extended family members, for example about whether it was true that the victim had experienced verbal abuse, physical violence, or other forms of violence.

Results

Across many regions in Indonesia, early marriage is usually triggered by various circumstances, including gender inequality, poverty, insecurity, and traditions (Grijns and Horii, 2018). In addition to limited economic resources and low level of education, early marriage is also inseparable from lifestyle development, prevailing discourses, and girls’ wish to get free from the constraints of their own parents. In this section, three specific recurring themes are presented: the factors that contribute to early marriage, the early marriage experience of abandonement and violence, and the early marriage experience of risks and impacts.

Factors that result in early marriage

This study finds that 60.3% of respondents (out of 300 respondents studied) still live in the same village with their parents, and even live with their parents-in-law in the same house. As many as 16.7% of respondents claim to live outside the village where their parents live - even though they are still in the same district. Only do 7.0% of respondents claim to live outside the district where their parents live. Meanwhile, 16.0% of respondents live outside the district, in the same regency where their parents live. Many respondents choose to live close to their parents’ or in-laws’ houses due to the fact that they are not yet economically independent, and they also claim that they need their parents’ help in caring for their children. In the extended family, some of the child care and domestic (household) errands can be and are used to being assisted by other family members, thus they are not oppressively burdensome. As many as 83.7% of respondents claim that they are unemployed when they get married. There are only 16.3% of respondents admit that they are employed when they get married. Since the respondents are in their teens, most of them are generally unemployed. In addition, after they graduate from elementary or junior high school, they are obviously unemployed. Due to that reason, most of them decide to get married at an early age.

There are various factors that encourage girls to decide to marry at a young age vary. There are some who enter marriage early due to influence from their social environments, and others do so because of poverty and pressure from their parents. According to Mulia (2015), there are, in general, two factors that motivate early marriage. First, most of society still upholds the cultural notion that daughters are na investment and that girls can be used as a means to improve the family’s economic situation, or at the least, girls can be used as a means to reduce the family’s economic burden. When families are faced with economic adversity, marrying off their daughters is seen as the quickest solution. Second, some still hold on to a biased interpretation of Islamic teachings, especially those associated with marriage requirements. The Quranic and hadith texts outline the requirements of being baligh (puber) and rushd (manifestative of prudence) for a marriage. Unfortunately, in practice, society interprets the requirement of baligh based on haid (menstruation), although, in fact, baligh refers to reaching adulthood physically and spiritually. Besides, the requirement of being rushd, which means matured physically, mentally, and spiritually, must also be fulfilled (Mubasyaroh, 2016). In the East Java province, particularly, what factors actually cause girls to get married at na early age?

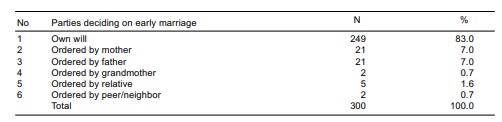

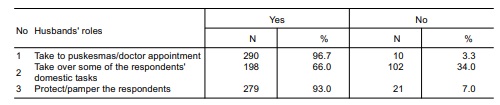

Although in some segments of society early marriage involving girls occur due to the parents’ pressure to reduce the economic burden of families, this study reached divergent findings. In ancient Javanese society, marriage occurred because daughters were forced into marriage by their parents. Marriage occurs because the choice of a mate is not based on the choice of children. But today, selecting a mate has shifted. The choice of a partner is not as extreme as it was in the past when the child’s mate was the choice of the parents and the child was not given the opportunity to choose his or her life partner. This study found that children can choose their life partner, while parents support their children in getting married younger to avoid the cost of living that their children represent. In other words, when children marry, it reduces the responsibility of parents. Most of the respondents (83.0%) stated that they agreed to the marriages on their own free will, while 7.0% were ordered by their mothers, 7.0% were ordered by their fathers, and the rest were ordered by their grandmothers, relatives, or peers (see table 1).

This study found that practically all the respondents (91.0%) interviewed selected their husbands on their own, in contrast to parents’ (8.0%) and other parties’ choices (1.0%) (see table 2). As teens, most of the respondents had been engaged in dating relationships with their spouses for some time before their marriages. Their decision to marry early was certainly influenced by social and cultural norms, as well as peer and parent pressure to a sizable extent. Some respondents replied that they married as soon as possible usually to prevent undesirable things from happening and, at the same time, to evade the gossip of their neighbors, as was the norm among the girls around them.

In relation to the phenomenon of girls and early marriage in the East Java province, 67.3% of the respondents were generally aware of the minimum age at which a marriage is legally allowed, but 32.7% were not. They decided to enter marriage early as it was acceptable in their social environments. A couple of the respondents even stated that their parents believed that marrying older than 19 years was, or was feared to be, late - something they saw as taboo.

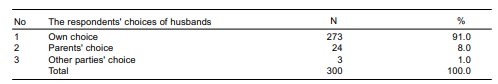

This study found many factors that encouraged girls to marry early. Marriage is an important stage in life; hence, deciding on when to marry certainly takes due consideration (see table 3). Nearly all the respondents (91.3%) stated that they chose to enter marriage at young ages as they had already fallen in love. It is presumed that this mindset of the respondents was influenced by movies or news about celebrities marrying young and the romanticism of youth. Some respondents conveyed that they frequently saw sinetron (soap operas) stories about the marriage of young people falling in love with each other, which are usually depicted as delightful. The reality, however, was different, they said, as what happened was unlike anything they had imagined.

Table 3 Factors encouraging early marriage

Note. N=300. Row percentages are displayed. Source: primary data.

This study found that 61.7% of the respondents chose to engage in early marriage to be independent of their parents and also to relieve them of some of the burden of caring for a child. Interestingly, as discovered here, 42.0% of the respondents decided on marrying early in order to escape from their parents’ constraints. Just like those who chose to find a job in the city and become migrants, this decision was not only based on their wish to be independent, but also on their wish to get out from under the control of their parents, which was considered restrictive and all controlling. As many as 23.0% of the respondents were married at an early age to avoid being labeled spinsters. Furthermore, 31.7% of the respondents married young because their friends had done the same. A habitat in which early marriage was common seemed to be one of the influencing factors of girls eventually choosing the same path.

The results of in-depth interviews show that parents supported their daughters’ decisions to marry at a young age, as revealed by Lis (17 years old):

I got married when I was only 13 years old. My husband, I chose him myself. I love him. He is my boyfriend. My father and mother did not forbid me to marry at that time, in fact my father and mother were happy that I was getting married soon. Yes…. Your father’s life is difficult, so if I get married, I will join my husband. I have many siblings and they are still small. At that time, my father was very happy that I got married.

Some girls marry because their parents have chosen a boy to marry their child, even though their daughter is still young, as was the case with Dea (18 years old):

I got married when I was 15 years old. Many of my friends my age are married. My husband is the ono f my father’s friend. At first I was afraid to get married because I was young, but in the end I wanted to. My father and mother always said they would get married soon, they were afraid they would not sell. If anyone wants to get married, get married quickly. Instead of being a spinster, people don’t talk well. Finally I wanted to. At that time I had no other choice.

For poor families, children usually hold some strategic role, particularly as a source of income for the families. It is normal for children to follow and help their parents at work. If they don’t help with the family livelihood, they usually get married to not be a burden to their parents. Indeed, when the respondents were asked to choose between working and getting married, some said either of the two options would be just fine (46.0%). However, not a few (39.7%) were more in favor of getting married than in working in the city. Of the 300 respondents investigated, only 14.3% preferred working to getting married. Many would rather start a marriage than work in the city because they believed that was the most realistic option available.

When asked to choose between getting married and going to school, the majority of the respondents selected the former (38.7%). As many as 37% of the respondents said that they would be fine with either, depending on the situation. Meanwhile, 24.3% were inclined toward pursuing studies at school.

That not many of the respondents chose to continue their studies was actually somewhat surprising. While for many respondents school is an ideal place for one to prepare and acquire social capital before work, for the majority of the respondents; thus, did not seem to be the case. Some of them stated that they did not feel like continuing their studies at school because in many cases school actually presented them with a burden. The obligation to study and complete assignments from the teachers, to some of them, was bothersome. In addition, they generally were aware that schooling was costly; education was often unaffordable for their poor parents. Although by schooling they could socialize and play with their friends, they admitted that in the environments where they lived, marrying early was preferable to continuing their education with children their ages.

More than half of the respondents (58.3%) admitted that they did not really feel they were burdening their parents, 22.7% reported that they sometimes did, and 19.0% of the respondents felt that they had become an extreme economic burden to their parents. In the midst of the slumping economy, many of the respondents were concerned about the economic condition of their parents and felt sorry for them. Marrying young, despite the many factors girls must consider, was believed to be the most realistic solution.

In the social environment where they resided, girls getting married older than 18 years was not a problem and did not generate gossip (78.3%). In urban societies, the way of thinking is admittedly changing. Yet, 8.7% of the respondents were still convinced that some part of society still regarded girls who did not start marriage young as spinsters. As many as 13% of respondents felt that most people gossiped about such girls. Some informants stated that in today’s society, there was no gossip about girls who were labeled as late-married or spinsters just because they did get married as young as most girls. Society has changed much from a decade ago. Still, among parents, the view that girls should not enter marriage late is still strongly upheld and is a particular belief.

When first married, 83.7% of the respondents said they were not expecting a child. However, 16.3% others admitted that they actually had conceived a child before their marriages. The majority of the respondents decided to get married not because they had committed a transgression, fallen into the wrong relationship, or any other reason that got them pregnant. For the societies in the Horseshoe region, the decision to marry young was integral to the prevailing traditions or habits.

Early marriage experience of abandonment and violence

There is a saying that marriage is like buying a pig in a poke. This means that no one really knows the temperament of his or her spouse or how his or her spouse actually behaved before marriage. There is an element of gambling in marriage as people, especially girls, have no precise knowledge or assurance of what they will experience after marriage. For those who are fortunate, girls will have good-natured spouses and live relatively harmonious family lives. However, for those who are less fortunate or ill-fated, married lives may be akin to a living hell, instead.

In addition to impacts on physical health, early marriage often had negative impacts on mental, emotional, and psychological conditions of the couples and their children (Pearson and Speizer, 2011; Mubasyaroh, 2016). Emotional instability in girls who married young may lead to domestic violence. Theoretically, age is one of the factors which influences emotional maturity. There is a period of transition from childhood to adulthood that starts with puberty, during which processes of physical maturity as well as social and emotional maturity take place. A girl is said to reach emotional maturity if, by the end of the teenage period (ages 17-22 years), she is able to control her emotions, understand herself, and critically judge a situation before reacting emotionally.

However, in cases of early marriage, girls and their spouses oftentimes have yet to reach emotional maturity, heightening the risk of disputes, divorce, and domestic violence (Pearson and Speizer, 2011). Domestic violence may leave trauma or even lead to divorce, which will harm the futures of girls. Separation and domestic violence may also impact the psychological state of the any children, who will experience a lack of attention and feel uncomfortable at home.

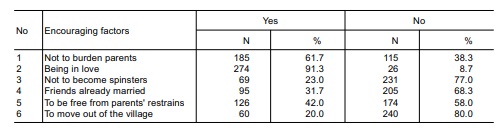

Although not through crude subordination or physical violence, this study found that most married girls generally felt the impact of the patriarchal culture that places men in a superior position. When the respondents were pregnant, most acknowledged that their husbands were responsible. This means that almost all respondents acknowledged that they are usually accompanied by their husbands when they visit the puskesmas (public health center) or doctor (96.7%) and as many as 93.0% of respondents claimed to feel protected and pampered by their husbands during their pregnancy (see table 4). However, as many as 34.0% of respondents informed that during their pregnancy, the husbands did not help with or take over responsibility for some of the women’s domestic tasks at home. The division of labor in couples where girls married at an early age is generally based on gender differences. Although 66.0% of respondents recognized that during pregnancy their husbands took over some of the household domestic tasks, that 34.0% did not help take over women’s domestic tasks shows that there are still many men who do not want to help their pregnant wives. Society is still patriarchal and considers domestic work to be the wife’s duty even when she is pregnant. This conclusion is reinforced by the results of in-depth interviews with women involved in early marriage.

Table 4 Husbands’ roles during the respondents’ pregnancies

Note. N=300. Row percentages are displayed. Source: primary data.

According to the 2013 U.S. Census Bureau, as quoted by Women’s Health, the recommended age for marriage on average was 27 years for women and 29 years for men. Psychology Today reported that women who are married after having reached adulthood and maturity will have more stable marriages than those who are married at young ages. This is logical, given that those who marry young have unstable financial conditions. Furthermore, girls who are married to equally immature partners usually have no experience with serious relationships. Data indicate that the rate of divorce is 50.0% lower for those who are married at the age of 25 years than the divorce rate of those who are married younger. Sociologist Nick Wolfinger in a study issued by the Institute of Family Studies which analyzed data from 2006 to 2010 and in the National Survey of Family Growth of 2011-2013 found an inverted bell curve, indicating that the probability of divorce tended to decrease with the increase in the age of the spouse to whom one was married until the late 20s and early 30s. This probability would generally tend to bounce back into the late 30s and early 40s.

The factors that lead couples to separate vary. The complicated adjustment process at the beginning of married life often worsens unless reconciliation and good adaptation are achieved as soon as possible. This study discovered that during the early stage of marriage, 45.0% of the respondents stated they had no problem in the adjustment process with their spouses. However, 35.3% recognized that they faced a few problems, and 15.0% reported that they often experienced difficulties. The study also found that 4.7% of the respondents constantly encountered problems at the beginning of their married lives. The respondents who have faced various problems since the onset of their marriages generally have a greater risk of being mistreated.

Among couples who are married early, the roles of women in the management of family’s assets generally are insignificant. This study found that 60.7% of the respondents had a major role in managing savings. Yet, only 31.7% played a major role in managing business capital. The same was the case in matters related to the family business, in which only 28.0% of the 300 respondents had a major part in the management of the family’s business.

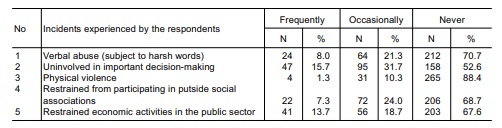

During the marriage, most respondents admitted to being subject to wide-ranging forms of violence, from verbal abuse to physical violence. This study found that 88.4% of the respondents had not experienced any physical violence (see table 5), 68.7% had not experienced any restrictions on their economic activities, and 70.7% never received any verbal abuse from their spouses. However, even if more respondents claimed not to have experienced violence, this does not necessarily mean that the respondents were not mistreated over the course of the marriage. As many as 8,0% or 24 of respondents who admitted that they often were subject to acts of verbal violence and as many as 21.3% or 64 women admitted that they were sometimes abused by their partners. As many as 10.3% or 31 respondents admitted that they sometimes suffered physical violence from their partners.

Table 5 Incidents experienced by the respondents during the marriage

Note. N=300. Row percentages are displayed. Source: primary data.

Women who marry at an early age often experience various forms of violence. As stated by Sar (18 years old):

My husband is often angry. Nagging and hitting me. Sometimes he gets angry for no reason. What I do is always wrong. If I fight, he gets angrier. He wanted me to do what he said. But even though I obeyed him, sometimes he still got angry. He also kicks me sometimes. Grabs my hair. Often. Countless times already.

Based on the results of the in-depth interviews, some women experience verbal/psychological violence every day. As stated by Mer (17 years old):

I was scolded every day. Getting scolded every day. It’s just that he’s angry. If my cooking is not good, he gets angry. He often said that I was a useless wife. Cooking not good. If he’s angry, I can’t answer. I have to be quiet. He said it was a sin if the wife dared to answer her husband.

The number of cases of violence is very large when viewed in a broader context. As the data on violence reported by Women’s Commission of the Republic of Indonesia, domestic violence is included in the category of violence in the personal realm. Data of National Commission on Violence against Women Annual Report of Republic of Indonesia or Komisi Nasional Anti Kekerasan Terhadap Perempuan Indonesia (2022) shows that there were 7,029 cases of violence during 2021, of which violence in the personal sphere ranks the highest at 5,243 cases or 74.6%. This data on violence shows that in the personal realm, violence is mostly experienced by women in the 14-24 years old age group, namely as many as 1,940 cases or 37.0%. This is the highest number of cases compared with the other age groups.

Early marriage experienced of risks and impacts

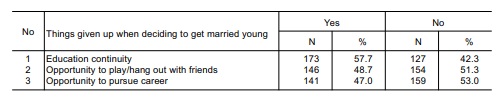

This study found that the respondents realized that deciding to get marry early would lead to a number of consequences. A total of 57.7% of the respondents had to sacrifice their education when they decided on early marriage. As many as 48.7% lost the opportunity to play or hang out with friends following marriage, and 47.0% lost the opportunity to pursue careers due to marrying young (see table 6). Getting married and, later, taking care of children, left girls with little time to do anything else outside the domestic affairs they were responsible for.

One of the reasons the respondents reported for getting married young was to live a better life. For the respondents’ families that were in poverty, marrying young was a solution to their economic problems. The study found that after marriage, most of the respondents reported that their economic condition had improved over that when they were still living with their parents. Twenty-five percent of the respondents reported there was no difference in their economic condition, and only 3.7% stated that their economic condition had worsened.

Economically speaking, marrying at a young age proved to be functional. Yet, would it be considered functional psychologically? This study found that more than half of the respondents (51.3%) did not experience any stress after marriage. However, 35.0% revealed that they occasionally felt stressed postmarriage, and 13.7% frequently experienced stress. The triggers of stress were many. Based on the in-depth interview results, most of the respondents stated that their stress stemmed from the incompatibility between the way their husbands actually were and how they imagined their husbands would be. Some respondents reported being mocked and suffering physical violence from their husbands. They generally experienced stress on a daily basis because they were worried about something undesirable happening.

Table 6 Things given up when deciding to get married young

Note. N=300. Row percentages are displayed. Source: Primary data.

Some of the interviewed respondents stated that during this period of being married, many things had triggered their stress, including having to deal with physically and verbally abusive husbands. In addition, the burden of household chores they were responsible for as wives was also stressful. As discovered through the interviews, in most of the respondents’ families, domestic tasks were entirely performed by the respondents (45.3%), 21.7% of the respondents claimed that domestic tasks were shared with their husbands, while many others (32.2%) said that the responsibility for most of the domestic tasks fell on them.

By bearing the considerable responsibility for the domestic tasks, there was not much the respondents could do. There was little possibility that the respondents could continue their studies at school or play an economic role in helping the family earn a livelihood. Indeed, 29.7% of the respondents were given full permission to pursue working in the public sector. Yet, 11.7% were only permitted to work after their children had reached a certain age and no longer needed the intensive care of the mother. As many as 30.7% were permitted to work in the public sector, provided that they remained responsible for domestic tasks, while 28.0% were not permitted by their husband to work at all.

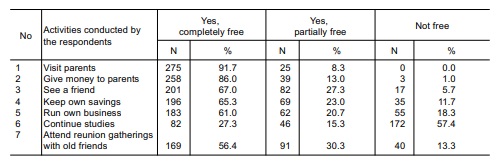

Most of the respondents were free to visit their parents (91.7%) and 86% of the husbands gave the girls money (86.0%) (see table 7). However, to conduct other social activities, such as continuing studies, 57.4% of the respondents admitted that they were not given as much freedom. Their husbands usually did not allow them to return to school as they had to take care of their child at home. This study found that 18.3% of the respondents were not free to run a business on their own after marriage; only 61.0% stated that they were.

Table 7 Husbands’ permission to pursue various activities

Note. N=300. Row percentages are displayed. Source: primary data.

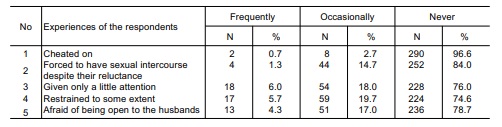

The majority of the respondents conveyed that during their marriages, they did not generally experience anything worrisome. However, this was not true for all respondents; 19.7% reported being occasionally restrained by their husbands, and 5.7% reported being restrained frequently (see table 8). Anything they did must have the approval of their husbands; hence, it was little wonder that some respondents felt restrained. Eighteen percent claimed that on some occasions they did not receive sufficient attention from their husbands, and 6.0% claimed they frequently did not receive attention from their husbands. Of the 300 respondents, 17.0% revealed that they were only occasionally open with their husbands and 4.3% reported that they frequently had to do the same as their husbands as they were worried that something bad or undesired would occur if they did not.

Table 8 Experiences the respondents received from their husbands after marriage

Note. N=300. Row percentages are displayed. Source: Primary data.

One of the most interesting findings in this study was that 14.7% of the respondents conceded that sometimes their husbands forced them to have sexual intercourse despite their reluctance, and 1.3% reported that their husbands often forced them to have sexual intercourse without their consent. Data from the interviews also show that the husbands often force their wives to have sex even though the women are reluctant to do so.

I was also forced to serve him in bed, even though I was sick, I was tired, he didn’t care. He will be very angry if I refuse his wishes. What can I do, in the end, I have to do what he wants. It didn’t just happen once, and it happened often [Ain, 18 years old].

I couldn’t stand living with my husband. But what are you going to do? I dared not fight my husband. Besides being angry, he also liked to hit me. Almost every day he asked for sex. Even though I was tired of taking care of children, I did all the household chores too. But he didn’t want to know. When he came home from work, he immediately played with his cellphone, he didn’t care about children [Den, 17 years old].

Data of this study shows that women experience various forms of violence. In addition to experiencing verbal/psychological and physical violence, they also experienced sexual violence. They are forced to have sexual relations even though they did not want to.

Discussion

This study found that early marriage is traditional in some of the societies in the Horseshoe region (Tapal Kuda) of the East Java province, Indonesia. In this region, girls married at age 16-17 is common. In some of the societies in the region, the 20s is late for girls to marry. Girls who have completed elementary education or have pursued religious education from pondok pesantren (Islamic boarding school) are usually married off quickly or get married to evade inappropriate rumors. Unlike urban societies in which women usually start marriage when they are older than 22 years, in the rural areas in the Horseshoe region, women who marry after age 20 will be labeled women as spinsters. Across the research location, it was normal for girls who had graduated from elementary school or junior high school to have the idea of marriage as soon as possible; they are considered ready to assume the role of housewife. In rural areas, the interest of girls in pursuing education at the university level was generally low. Rather than budgeting money and savings so their daughters could complete their education at university, most parents in villages were more inclined to marrying off their daughters as soon it was considered realistic.

Moreover, among the communities in the Horseshoe region, nikah siri, or marriages that are legal religiously but unregistered at the KUA, are very common and considered valid. For them, the most important thing is that the children do not commit zina (adultery) practices. Nikah siri is valid when seen from the perspective of the religion they adhere to. The term “kawin pemutihan” or marriage verification is also popular in this area. This refers to conducting an official marriage ceremony after the couple engages in nikah siri, in which case authorization is requested from the KUA after the minimum age is reached.

Girls who have grown up in communities where the majority of their peers and family members are married early are, to some extent, encouraged to do the same. This research found that girls are not only victims of what is considered a counterproductive cultural practice for their futures, but also a reflection of the limited choices they have. As with Kooij’s study (2016), this study found that the limited premarital decision-making, poor level of education, and wrong cultural backdrop all take girls unknowingly into married lives, robbing them of their time as children. The various efforts made by social institutions and children’s rights activists to prevent early marriage often fail or have yet to show desirable outcomes. Across many areas and communities in East Java, early marriages are still pervasive and harmful to girls (Djamilah and Kartikawati, 2014).

Many girls who are married at younger ages are generally not allowed an to participate in the daily decision-making process of their families (Bloom, 1996; Schlecht et al, 2013; Mubasyaroh, 2016). As found by Parsons, Edmeades, Kes, Petroni, Sexton, and Wodon (2015), they are also prone to drop out of school, participate less in the workforce and earn less as laborers, and have less control over productive household assets. Girls who work at young ages usually also undergo harmful, difficult, and complicated childbirths and are generally less healthy. It is also likely that the infant mortality rate for young-age mothers is high. Ultimately, as a result of early marriage, the economic impacts and the high marriage costs incurred often lead to successive generations of poverty (Parsons et al., 2015; Biswas, Khan and Kabir, 2019).

This study found that not all girls who are married young have a better socioeconomic condition than before marriage. Parents of poor families who marry off their daughters in hopes that their daughters will become free of the pressure of poverty often turn out to fall even more deeply into poverty after their daughters’ marriage instead, as they must bear the burdens of their daughters and the life needs, which are not small. Many girls who have already been married still live with their parents as they have yet to own a house (Biswas, Khan and Kabir, 2019; Chauhan et al., 2020).

The dreams of joyful days throughout marriage do not always come true. Many millennial girls who are accustomed to watch television and consume romantic stories over social media admit to imagining and hoping for happy marriages. However, the reality is not always as expected. In this study it was found that those who were married young turned out to have experienced restrictions on their mobility in various forms, and a few even experienced marital rape. Some revealed that they were forced to serve their husbands through sexual intercourse.

It was also found that some girls were fortunate that, despite their early marriages, they did not experience many problems in their married lives with their spouses. The support of husbands in the form of cooperation with and assistance to the wife in the completion of domestic tasks is often a pleasure for the girls. Unfortunately, although most of the respondents said that their husbands helped them, for example by taking them to the doctor for a pregnancy check-up, most domestic chores were still carried out by the majority of respondents in this study. Traditional understandings of gender roles still dominate the these early marriage partners. The role of men as husbands, fathers and heads of the family is traditionally understood as being unwilling to perform domestic tasks that are considered the domain of women or wives. The attention given to the wives during pregnancy is also influenced by their attitude toward fatherhood as the dominant significant others in the family.

In most cases, girls who were married early were often subject to subordination and acts of violence by their spouses. In the study by Zakar, Zakar, and Nasrullah (2014), a third of females aged 15-24 years in Indonesia and Pakistan were reported to experience and fall victim to their spouses’ acts of violence. The violence received by girls who were married young took the form of verbal abuse, psychological violence, and physical violence, including actions considered domestic violence (Pearson and Speizer, 2011; Djamilah and Kartikawati, 2014). Based on the in-depth interview results, the researchers found that the domestic violence experienced by many respondents in this study was correlated with their immature emotions, a rushed marriage process without knowing their future husband very well, and the social, economic, and cultural burdens as “young wives” and housewives who must be ready to serve their husbands in marriage. Continued domestic violence that gets worse in early marriage usually results in divorce being initiated by the girls. However, it can also happen that the girl maintains her household despite experiencing violence because she has no other choice.

In Indonesia, many efforts have been made to prevent girls from being victims to early marriage (Fadlyana and Larasaty, 2009). However, eliminating early marriage in society is not without its challenges. The efforts to prevent early marriage are often challenged by the traditions and beliefs in society. In Ethiopia, for instance, Boyden, Pankhurst, and Tafere (2012) showed that the efforts to prevent early marriage failed because their did not greet and pay attention to the local culture. Arguments that position societies in which early marriage is common as being backward, unintelligent, or behind the times will result in alienation and the rejection of any advice as going against the prevailing culture.

In many cases, early marriage prevention efforts are not effective if they solely rely on regulations and penalties (Bloom, 1996). Increasing the minimum age for girls to marry to 19 years will indeed serve as a robust foundation to drive up female marriageable age. Yet, beyond just increasing such an age limit for girls to marry, it is also important to use approaches that will win the support of local communities. Experience teaches that efforts to engage in social engineering and prevent girls from taking the wrong path will need the support and participation of watchdogs from the local society itself. Without the commitment of the people and local communities, efforts to significantly lower the rate of female early marriage will fail. Socioreligious institutions committed to early marriage prevention will play various roles. In reality, however, the fight of local social institutions to prevent early marriage will likely face the challenge of the traditions in developing societies (Grijns and Horii, 2018).

Other than the local community support, efforts to prevent early marriage also rely on government intervention programs (Fadlyana and Larasaty, 2009; Malhotra, Warner and McGonagle, 2011). By incorporating early marriage prevention efforts into people’s welfare improvement programs, significant impacts are hoped to be generated as one of the sources of early marriage is the life pressure poor families are under.

To reduce and prevent early marriage in the East Java province in particular and Indonesia in general, there are some things to which attention should be paid in the future. First, to protect girls from early marriage risk, one of the measures that can be taken is to provide sufficient access to formal education (Priohutomo, 2018). Encouraging and offering wide opportunities for girls to continue their studies will not only bring economic benefits for the girls themselves but also for the country (Malhotra, Warner and McGonagle, 2011). A large body of research has proven that highly educated women will have better opportunities for stable employment and will eventually contribute to the economy of the country. To make sure that girls continue their education and to prevent them from marrying early, the government should ensure that girls exercise their rights to participation in the compulsory 12 years education program, which is equal to the level of senior high school.

Second, it is necessary to develop special education for girls and youths in general on education and sexual reproductive rights. Numerous studies proved that girls’ lack of knowledge of reproductive health and how they should keep their own safety is one of the reasons why early marriage still persists (Priohutomo, 2018). To some degree, there are still many girls who are unaware that engaging in sexual intercourse will make them pregnant and then force them to marry young. Many girls also have knowledge that early pregnancies will put them at twice as great a risk than pregnancies in their 20s.

Third, it is necessary to socialize matters on gender equality among girls, especially those in the Horseshoe region. Girls should not only be educated on how they should maintain and respect their own bodies, but also on why it is important to build a marriage based on the principles of equality and respect for women. Over time, society will develop the view that females are considered ready to enter marriage when they have acquired the ability to manage a family, while for males, when they are ready to marry is seen in terms of whether they are able to earn an income on their own. The idea of building a marriage in the context of unequal relations and men’s superiority should be eroded, as families should be built on equality (equal family).

Fourth, it is necessary to develop a counter-discourse which opposes those cultures that still regard early marriage as necessary (Malhotra, Warner and McGonagle, 2011). In the societies in the Horseshow region, we know that there are still many who think that girls should be married off upon their first menstruation to prevent them to engaging in free sex behavior. If such a view is allowed to drag on, it will be counterproductive for efforts toward girls’ empowerment. Therefore, society’s social construction, which is biased toward patriarchal ideology, should be deconstructed and remade with a new discourse on a more promising future for girls.

Conclusion

This study has found that the root causes of early marriage are not restricted to economic reasons, but also involve sociocultural factors. Poor education and patriarchal ideology to some degree also influence the perspectives of those who support female early marriage. Unlike society’s hopes and beliefs that marrying young is a promising solution for girls’ futures, this study found that some girls are at risk of sustaining harm from various things such as stress and even abusive acts by their spouses.

This current study found many causes of early marriage in the Horseshoe region (Tapal Kuda) on the eastern part of Java island, in East Java province, Indonesia. Other than economic factors, the study also discovered that early marriage is also affected by poor education, the culture or view in society that still regards girls who marry later as spinsters, and strong traditional norms. To some girls, changes in the value system in society and the patterns of girls’ associations that are relatively more permissive also influence premarital sexual relationships and undesired pregnancies.

The impact of early marriage differs from one girl to another. Girls who are married early are at risk of not only medical problems but also being prohibited to pursue education and work opportunities due to responsibilities for domestic work. Early-age marriage burdens girls with responsibilities as wives, sexual partners, and mothers, roles which are supposed to be played by adults and which girls are not yet ready to assume. In some cases, early marriage is also closely related to the possibilities of intimate partner violence, or at least verbal abuse that hurts their feelings.

This research on early marriage in the Horseshoe region (Tapal Kuda) in East Java province, Indonesia, has complemented other studies. In particular, this study has made an important contribution to the existing research by using the qualitative approach that was previously not used by early marriage researchers. With this in-depth interview data that complements this study, the “voices” and subjectivity of the victims of early marriage can be heard and better understood. In addition, this research also brought an important strength related to the impact of early marriage in Muslim countries, particularly in Asia and Southeast Asia. As a country with the second largest Muslim population in the world, Indonesia has a very strong influence of religious views in any aspects of life. In the previous studies, the influence of religious values and teachings on early marriage practices has not been widely studied.

However, this study also has a number of limitations. Research that is local in nature should be assessed carefully and not understood as generalizable to all of early marriage. In addition, the lack of previous studies on early marriage in Indonesia is also an obstacle to obtaining in-depth data on the subject. Therefore, further research on early marriage can perhaps be carried out by considering these weaknesses. Future studies that are more global or cross-country, comparative studies with multiple variables, and studies that are more focused on preventive efforts should be carried out so that the practice of early marriage and its negative impacts do not continue to take place.