Introduction

Populism appeared between 2016 and 2022 as one of the main challenges to the stability of liberal democracies.1 The victories of the Brexiters in June 2016 and Donald Trump in the US presidential election of November 2016 triggered a long potential reshuffle on how the relationship between representatives and represented is built.

It must be said that the Brazilian and Italian contexts that triggered the rightist populist wave were very different. In the first case, the rise of right populism was the consequence and took place in the aftermath of a long wave of left populism established through the victory of the PT candidate, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, in 2003. In the Italian case, populism was triggered by the economic crisis of 2008 and the subsequent technical executive, led by Mario Monti and supported by almost all the parties. In both cases, however, populism was a reaction based on the need for the subject or topic to cover all aspects amid a solid political crisis.

In this context, the results of the 2018 and 2019 elections in Italy and Brazil must be taken into account. The League increased its vote share from 4% to 17% in the Italian political elections. After the election, a populist government was formed with the 5 Star Movement (Movimento 5 Stelle). After a few months, in the 2019 European elections, Salvini’s party increased its vote again to 34%. In October 2018, Jair Bolsonaro won the Brazilian presidential election (first run 46% / 29% and run-off 55.13% / 44.87%).

For both countries, Italy and Brazil, the populist wave seemed to enable the entire political framework to be revised. However, the League’s upturn in popularity appeared to diminish after the initial powerful push. Italy and Brazil reacted differently. In Italy, the populist wave shifted from one party, the League, to another, the Brothers of Italy. Jair Bolsonaro was defeated in Brazil but continues to be a contender.

The paper will be divided into three main parts: Introduction - in this section, the cases and the methodology will be presented. The second section will divide and develop the analytical sections into three main dimensions: the leader, the ideology, and the audience. In the third section, the results will be summarised.

The populist way to represent the people

Representation is generally theorised in a liberal-democratic context. Pitkin came up with the most famous definition in portraying it as a way to “make present again”. Therefore, following this definition, political representation makes citizens’ voices, opinions, and perspectives “present” in public policy-making processes (Pitkin, 1967). This paper aims to define the populist way of representation as a model and not a disfiguration of the liberal-democratic ones. The main aim is to analyse whether or not we can speak about a specific form of populist representation as being qualitatively different from the liberal democratic one.

Populism has been mainly described as a sickness of the liberal-democratic model. We advance here the hypothesis that it is a model per se. Following Urbinati’s conceptualisation, populism is a form of “degeneration” of the democratic representation, which inevitably ends up as a form of a distinctive representation model. Laclau and Urbinati agree in underlining that populist logic is fuelled by some forms of delusion or distrust in view of how it works in a liberal democracy. Demands not fulfilled within the liberal democratic representative framework will seek to be answered outside. To build this “outside”, a populist model of representation is needed. Following Laclau’s thought, populism must be conceived as a political articulation rather than as a specific ideology. As stated by Laclau, “Populism itself tends to deny any identification with or classification into the Right/Left dichotomy. It is a multiclass movement, although not all multiclass movements may be considered populist” (Laclau 2005: 4). From this, we can deduce that the imprecision or vagueness that constitutes the language of a populist discourse does not have any pejorative connotation. In Laclaunian terms, ideological imprecision is an essential component of any populist phenomenon since it operates performatively within a social reality that is largely heterogeneous and fluctuating (Laclau, 2005: 118). This is why the article will focus on how the populists build their audience and the specific relationship between represented and representatives.

To understand the populist representation, two dimensions are crucial. The first dimension is related to the political subjects that will be represented by the leader, explaining how the bonds between him/her and his/her supporters are established. The second dimension aims to describe the effects of this new conformation on the political system. The non-mediated link between the leader and the people (the main aim of the populist representation) is closer to the organic representation rather than the individualistic liberal-democratic one. In the populist Laclau’s logic, the people are more than a sum of individuals; they are a body in which the individuals are a sort of atom. In this case, the definition of legitimacy given by Carl Schmitt helps us to better understand the populist phenomena (Schmitt, 2004 [1932]). The contrast between legitimacy and the rule of law, highlighted by the German constitutionalist when he refers to parliamentarianism, must be resolved, and the legitimacy of the people must prevail over the rule of law. In this context, representation is the outcome of two actors: the claim maker or the leader, as Saward (2010) explained, and the audience or the people. This relationship is never exclusively top-down but is at the same time top-down and bottom-up. There is a twofold relationship between the “claim maker” and “the audience” (Saward, 2010). Hence, the main enemy of populism is not democracy per se but liberal and representative democracy. However, here is the question: How can a populist democracy be ruled? That is, populism is not just a demagogical rhetoric used by charismatic leaders to boost their audiences; it is also an overarching framework to establish the relationship between citizens and power. In other words, it must also encompass how the rhetorical discourse is translated into a consistent institutional apparatus to overcome all the intermediate bodies that separate the leader from the audience (Laclau and Mouffe, 1985).

As Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe stated in Hegemony and Socialist Strategy, the agent (the representative figure) in the political dimension functions as a constitutive exterior (Laclau and Mouffe, 1985). Its role is to transform a set of social subjects into a cohesive political subject (Laclau, 1994), that is, the people. This means that any social objectivity is constituted through acts of power, since the constitution of an identity is always based on exclusions that establish a violent hierarchy between the resultant two poles. No matter what, this identity shows traces of this exclusion, which governs its constitution, what we can call its “constitutive outside” (Mouffe, 1993: 141).

This is the process that, twenty years later, was named by Ernesto Laclau (2005) “the populist reason”; the reason that is conceived as a dynamic of representation through which the bonds between leaders and followers are formed. According to Laclau, such a relationship is constitutive of every political subject. The specificity of populism, in turn, is that the connection between different social groups will shape the people. Another group, identified as the “enemy”, creates this connection through the perception of a common threat (Silva, 2018). By incorporating the “populist reason” as an explanatory hypothesis about the origins of political identities, which necessarily presupposes the presence of a constitutive exterior, these exclusions do not need to be justified by criteria beyond those conferred by the political struggle for hegemony. The speech leader points out the common enemy, and it is through the identification that the equivalence chains are created, bringing the different social subjects closer together.

Ernesto Laclau introduced the concept of an equivalential chain in his book Politics and Ideology in Marxist Theory. In the text, the category is defined as a chain of demands not necessarily related but linked together through a common, empty, and floating signifier with no inherent meaning and can be filled with different meanings depending on the context. Claude Lévi-Strauss introduced the concept of floating signifiers in his work on Marcel Mauss. According to Lévi-Strauss, these signifiers are “floating” because they are not connected to particular signifiers and specific meanings. Instead, they represent an undetermined quantity of signification devoid of meaning and thus apt to receive any meaning (Lévi-Strauss, 2013).

In other words, the equivalent chain is a chain of demands linked together through a common signifier. This empty signifier can be filled with different meanings depending on the context. This chain of demands creates an unfulfilled totality, inside which one signifier subordinates the rest and assumes representation of the rest via a hegemonic process (Laclau, 2012).

It will be through this theoretical framework that we shall understand Bolsonaro and Salvini’s rise through the dissemination of right-wing discourses, capable of spreading the perception of threat and hostility towards the Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT), in particular, and the left in general, such as in the impressive rise of Matteo Salvini through an identarian discourse - in which religion is one of the primary sources of legitimation (DeHanas and Shterin, 2018) - based on the dichotomy of us (white and Catholic) and them (non-white and Muslim).

Populism is a form of representation per se that is quantitative and qualitatively different from representation in a liberal-democratic framework. It is closer to organic representation since it is built over an idea of the people not as individuals but as bodies (“the People”) more than the representation of the individual interests. To do so, the populist leader, in order to be successful, needs to transform the “liberal” delimitations of the power described in the constitutions.

The dimensions of the populist representation

Brazil and Italy, Jair Bolsonaro and Matteo Salvini; two countries and continents with different contexts, institutional structures - presidentialism toward parliamentarianism - and other social structures. However, there are several aspects in common: being the leader of a weak or almost non-existent party, being in power, and being supportive of very conservative values; a fragmented party system that undermines the consistency of leadership. These factors are the reason why analysing Jair Bolsonaro and Matteo Salvini comparatively is exceptionally fruitful in understanding the intimate meaning of populism.

Following Urbinati and Laclaus’s insight, populist representation could be operationalised by three analytical dimensions. Firstly, the leadership, defined by Saward as the “claim maker” or, in Laclau’s terminology, “the agent”. The leader is the centrepiece of the entire populist structure, who must be, at the same time, charismatic and centralised, being directly connected to the people by figures that act above the political system and are the instrument of constructing the equivalence chain. Secondly: the ideology. Ideology plays a crucial role in the construction of political subjects. It is through the boundaries made by political issues that the identity of the people is built. It is within a confrontational and dichotomic logic that the people is constructed. Thirdly: the audience. The social subject became political through a constitutive process in which two actors are the audience and the agent. In this context, the audience is not just a passive actor. The populist leader has to transform a shapeless audience into definite people with boundaries and a feeling of belonging. In doing so, ideology is certainly the vector. Still, this vector must be consistent with the categories of the society that the agent wants to transform into a cohesive political subject.

The leaders

The Brazilian captain

The populists’ rhetoric claims that the people’s power has been stolen by professional politicians, an argument that fits very well into the Brazilian context and has existed since 2014. Bolsonaro does not escape this framework and, despite his longstanding political career and the fact that he left the army in 1988, he rejects being defined as a professional politician and, in his Twitter account, Bolsonaro presents himself as a captain in the army.

Bolsonaro’s political activity has never been directly connected to a specific party. After his brief passage through the Chamber of Councilmen, Bolsonaro ran for Federal Deputy in 1991 and remained an MPS until he was elected President in 2018. He was elected by several parties, among them the Partido Democrata Cristão (1989-1993), the Partido Progressista Renovador (1993-1995), the Partido Progressista Brasileiro (1995-2003), the Partido Trabalhista Brasileiro (2003-2005), the Partido da Frente Liberal (2005), the Partido Progressista (2005-2016), the Partido Social Cristão (2016-2017) and the Partido Social Liberal (Social Liberal Party PSL).

Before he was elected as President of Brazil, the political performances of the “Captain” were abysmal: in his first election for Federal Deputy (1990), Bolsonaro obtained 67,041 votes; in the second (1994) 111,927; in the third (1998) 102,893; in the fourth (2002) 88,940; in the fifth (2006) 99,700; and in the sixth (2010) 120,000. It coincided with the 2014 political crisis, brought about by the Car Wash process (Lava Jato process), when Bolsonaro’s political career started to gain relevance. In the 2014 legislative elections, he gained 464.572 votes, being the most voted-for congressman from Rio de Janeiro and among the country’s five most voted-for federal deputies.

Even considering this meteoric rise between 2010 and 2014, it is essential to underline that Jair Bolsonaro was promoted to the most critical position in the Brazilian executive without ever having played a role in this power sector before and without any significant achievements.

Therefore, to understand the ascent of Bolsonaro, it is crucial to consider the constellation of factors that afforded him the potential to expand his base and build up a legion of supporters. It is in this dynamic that the original agenda (military) begins to share space with other demands to be articulated in the chain of equivalence formed in his discourse, whose nodal point is the contraposition with the left, associated with political and moral corruption, and the antagonism with PT and its prominent leader, Lula.2

In a superficial analysis, we can grasp some attributes of this new political subject that was formed around Bolsonaro: this was a group identified with the symbols of the middle and upper classes, which identifies itself with conservative issues, with the nostalgia for the military dictatorship (1964-1985),3 with the promotion of religion and the reduction of the role of the state; three of the fundamental elements to contrast Brazilian decadence, and a policy that presents itself as “far right”, in favour of a presumed majority, hampered by PT governments, and made up of the white heterosexual middle-class.4

The League’s leader

Matteo Salvini was directly elected the Northern League’s federal secretary in primary elections on 7th December 2013. Similar to Bolsonaro, Salvini’s nickname is “The Captain”. In 2012, Carroccio’s party was experiencing its most profound crisis since its official foundation as a party in 1991. In September 2012, the party was shaken by several corruption trials, one of which directly involved its founder, Umberto Bossi, the charismatic former LN leader (McDonnell, 2016). Inevitably, there was a sharp downturn in the party’s results in the 2013 elections. LN garnered only 4% of the share; that is, only half of the votes won in the previous elections 2008. Over this period, LN’s leader was Roberto Maroni, former interior minister from the party’s conservative wing. On 23rd September 2013, the League’s Federal Council, in a desperate attempt to overcome the crisis, called for an election in December of 2013 to appoint a new leader and for a programmatical congress to revamp the party.

For the first time in the League’s history, the members were allowed to vote directly for their leader through primary elections. The poll results were ruthless, as Bossi was heavily defeated by Salvini, the supposed outsider, who was elected with an 80% share of the thousands of the League’s militant supporters.

Although the basic assumption of Salvini’s official rhetoric is based on the idea of the newcomer, not compromised by the LN’s corrupt political elite, that is entirely and somehow paradoxically untrue. Salvini has been a member of the LN since 1990, a representative at the Milan Council from 1993 to 2006, an MEP from 2004 to 2014 and, ultimately, an MP in the Italian parliament.

Furthermore, during his political career. Salvini has played several propaganda roles. Firstly, he was a journalist for the party newspaper La Padania, then at Radio Padania, where he was director from 1999 to 2013. Thus, for 20 years, Salvini has dealt with the media rather than playing leadership roles at a national or regional level. Therefore, the League’s leader has developed solid media and communication skills.

During his political career as part of the propaganda branch of its party, Matteo Salvini has developed a strong and helpful capacity in demagoguery. The League’s leader has always run, not along, but beside the party and the institutions. His attendance at the European Parliament and in the offices of the Interior Ministry are very few, while his attendance at social media and street events are multiple. Since he was elected Secretary of his party in 2013, he has frozen the intermediate body of this party and has run it on his own (Diamanti and Pregliasco, 2019).

It is worth underlining that, similarly to that of Jair Bolsonaro and Donald Trump, Salvini succeeded in what some would describe as a miraculous way: inheriting a weak party and making it into the top force in the country. After being appointed Interior Minister, the number of communication staff has been consistently increased. Outside the League party’s structure and under Salvini’s tight control, a vast social media structure called “La Bestia” (The Beast) was created.

To sum up, the Captain’s communication strategy is composed essentially of two main layers. The first layer focuses on real life: that is, streets, markets, events and so on. This is where the content to be shared through social media is produced: selfies, the leader’s speeches, crowds surrounding the leader, et cetera. The second layer is the official social networks like Twitter and Facebook. This is real life, where the content is released and analysed and where followers can share, comment and the like (Bobba, 2017).

Ideology

Religion and economic liberalism: the old and the new in the discourses of Jair Bolsonaro

Religion represents one the most essential, critical factors in understanding the Bolsonaro maxim; “Brazil above us, God above all”.5 Despite being Catholic, he also enjoys powerful support from the evangelical community. This process of approximation has been built gradually through the incorporation of a conservative moral agenda centred on fighting public policies geared to gender issues, as well as against abortion and same-sex marriage. In 2011, when the Brazilian congress discussed the vote on the 122/2006 bill, also known as the anti-homophobia law, Bolsonaro launched himself as one of the leading spokesmen of conservative reaction.

It should be noted that there was an intimate relationship between the growing popularity of Bolsonaro and the discursive line he adopted on the verge of the presidential election 2018. In Brazilian political history, no presidents have been elected by popular vote that could be directly identified as conservative or right-wing. The strong adherence of Christians, especially Protestants, to Bolsonaro’s propaganda revealed the growing importance of an agenda associated with religious, traditional and conservative values so that his speeches could extend their penetrative effect. Furthermore, it is essential to highlight the role of the facilitators exercised by religious leaders, mainly of the Pentecostal denomination, within social groups of this population segment. Using their great prestige, they have enabled the spread of their proposals by acting directly with their congregations.

Aggregating demands from different conservative segments constructed the chains of equivalence from his discourse. First, the military and admirers of the dictatorship led by them, then the religious segments identified with positions contrary to the advancement of policies oriented to gender issues and the legalisation of abortion.

There is, however, an exception in which we can observe a rupture in the speeches made during the Bolsonaro trajectory: the economy. This can be understood as the last discursive movement of the former congressmen as it marks the consolidation of his ambitions as a candidate for the presidency, being able to rally majorities through speeches that can be typified as populist precisely because of this hegemonic pretension, geared to overthrow the “block in power”. In this process that contemplates the mutation of a corporatist representative of minority groups into a leader of the masses, the most recent agenda to be incorporated in his discursive performances was the defence of liberalism/economic orthodoxy, which allowed him to win the support of the financial elites and the middle classes identified with this discourse. Two months before the election of Lula to the presidency in 2002, Bolsonaro declared that if his candidate (Ciro Gomes, PPS) did not reach the second round (as he did not), he would support the PT candidate.6 However, some months later, Bolsonaro initiated a series of criticisms of the Social Security Reform, sponsored by PT, for being excessively draconian and for his neoliberal orthodoxy. In 2004, this criticism began to be linked to the theme of corruption. Since then, the congressman has initiated a process of radicalisation of his attacks against the PT, in which he combines the association of party members who participated in the guerrilla war against the dictatorship with compliments to the military for having managed to eradicate this communist threat.

In addition, Bolsonaro’s speeches addressing the economic plan reveal a criticism of the PT’s redistributive policies (in terms of taxation and regarding the public policies directed at the popular classes, as is the case of Bolsa Família) that are focused on the lower strata of the economic pyramid, and, because of that, would have undermined the “real working class”. From then on, Bolsonaro presents himself as a representative of this affected majority (plebs) for the sake of a minority favoured by PT’s policies.

Religion, nationalism, and identity

The transition from Northern League to League is not merely an act of reshaping the party’s name, but it unveils a consistent ideological change. One prevails over the other: the new League ceased to be a regionalist party to embrace a nationalistic stance. The Northern League’s main aim was to increase the autonomy of the regions of the north of the country. At the same time, the Salvinian League’s central claim is similar to that of the Marine Le Pen’s party: to put the Italian first and, clearly, the immigrant second.

Anti-Europeanism and sovereignism are the ideas that Italy should fight for more considerable independence toward the European Community, and traditional values are the two main dimensions that shape the new League’s ideology.

Therefore, the Salvinian League shares the central values of other radical right parties built on three main pillars: the idea that national laws should have primacy over European laws, that religion should be the utmost framework of the Italian identity, and to restore popular power through a profound reform of the institutional framework.

Roots and identity play a central role throughout the structure of the League’s party. Christianism represents, at the same time, the border and the identity of a new community that is supposed to be rebuilt (Caiani and Carvalho, 2021). The radical right parties (RRP) do not necessarily act coherently or follow the official church, but they build in their way to translate Christianism. Despite the secularisation of Italian society, battles against progressive values are far from secularised. Although religion is not conceived as a faith in terms of attendance, Christian values are considered a source of inspiration for legislation.

However, what is essential to pinpoint here is the association of religion, not merely as a fact of faith but as an identity. As Baumann (2001) explained, the fear of globalisation fosters a backslash that fuels the vote for parties that appear to be the defenders of traditional values.

There are two layers of such an ongoing process: a nostalgia for a lost past and a wish for a new community established around the symbolic.

While religion represents the shared values of the Italian community, a new institutional framework represents the way to gather together that community against the political elite and around the people’s will. Contrary to the Brazilian case, the Italian political system rejects any direct election of the state’s body as the election of the head of state. To connect the leader with the people, it is necessary to enact a comprehensive constitutional reform. The programme presented by Matteo Salvini for the Italian legislative election held in March of 2018 included an extensive section on that subject - “Giving the people back their sovereignty”.

The League’s manifesto states, “Democracy means the rule of the people”. The bodies of representative democracy are blamed for having stolen the people’s sovereignty; therefore, it is necessary to “develop the institutions of direct democracy”.

The central axis of the constitutional reforms proposed by the League’s manifesto is built around restructuring the three branches of political power: executive, judicial and parliamentary.

The executive has to become the prevalent body in the hierarchy legitimated by the “direct election of a strong Head of the Executive” (La Lega, 2018) that “must not be appointed by parliament” (La Lega, 2018) and should also be the “Head of State” (La Lega, 2018). The independence of the judicial branch and the judges is significantly reduced and subjugated to politics in two main ways. On the one hand, “Judges must apply the law and not make it” (La Lega, 2018). On the other hand, constitutional judges must be elected by the head of the republic (executive branch), parliament and the regional assemblies. No role is given to the judicial branch in the selection process of the constitutional court judges. Last but not least, it is proposed to abolish “referenda’s minimum quorum to increase their effectiveness” (La Lega, 2018).

The people/community have become the primary source of any legitimation, systematically more significant than the rule of law. This happens through referenda reform, the direct election of the head of government and the state and the limitation of the independence of both MPs and judges.

The rhetoric of the stolen sovereignty is transformed into a directly exerted and illiberal democracy in which the hidden, implicit and inevitable output is, as explained by Nadia Urbinati (2014), plebiscitarian.

The audience

Bolsonaro’s popularity

Jair Bolsonaro is a consistent politician in terms of speech and practices; in the same way, his support among the popular segments has a pattern over time. His main support groups are the army, public security agents and individuals who identify themselves with a military idea of order structured by a patriarchal and reactionary conception of family.

So far, Bolsonaro fits the pattern of other far-right leaders like Matteo Salvini. However, when we observe the social demographic profiles from the surveys carried out right after his election in 2018.

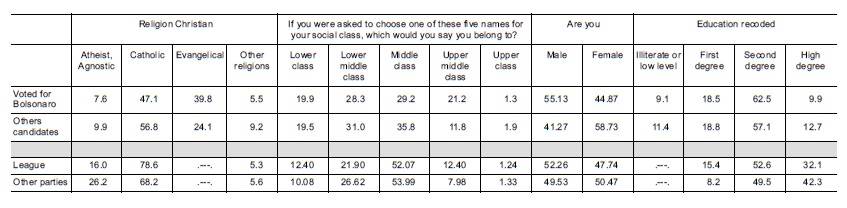

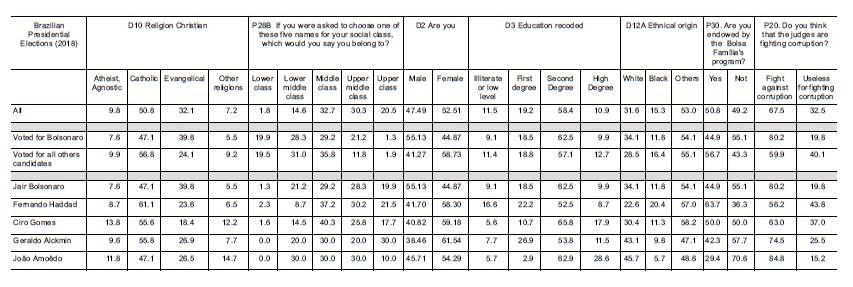

An analysis of the electoral survey released in 2018 by the Center for Studies on Public Opinion (Cesop, 2018) shows the main components of Bolsonaro’s electorate. We divided the dimensions into two different levels (table 1). First, the general dimensions: religion, social class, male/female, education and ethnical origins (this latter only for the Brazilian case), and two dimensions proper to detect the triggering factors that bear Bolsonaro’s victory: to be part of Bolsa Familia’s programme and to be in favour of or against the corruption trials.

Table 1 Bolsonaro’s Voters and their values - (All - Bolsonaro and others - Main candidates) - Presidential election

The first division among the five leading candidates is the feeling of belonging to a religion (table 1). Bolsonaro’s voters are the least atheist or agnostic (only 7.6%) and by far the most evangelical; almost 40% of all voters of the five leading candidates. While it is among the voters of Fernando Haddad that we found the highest rate of Catholic voters (61%), the differences between the self-position of the social classes are nuanced and contradictory. While Bolsonaro has a low average number of voters that belong to the lower class, the main difference with the PT’s candidate, Haddad, is the average number of voters belonging to the lower-middle class, with Bolsonaro at 21% and Haddad at 8.7%. The second highest difference is among middle class voters, where the difference between the populist leader (29%) and the leftist (37%) is more substantial (table 1). Among the five leading candidates, Bolsonaro has the highest average of male voters (55%), compared with his primary challenger, Fernando Haddad. Literacy is the second cleavage, in having completed a double degree or a higher degree is part of Bolsonaro’s voter profile (62% second degree, 10% higher degree).

Haddad’s voters are more nuanced and anchored to the lower strata (16% are illiterate or with a lower degree, 52% with a second degree and 8% with a higher degree). Among the two leading candidates, being a white voter is another factor. Comparatively, Bolsonaro and Haddad are set at 34% to 22%.

There are two more divisions regarding the triggering factors: being endorsed or having had some relative that has been supported by the Bolsa Familia’s programme, where voters for Haddad make up 63.7%, a more significant percentage than those of Bolsonaro (44.9%), and to be supportive of the anti-corruptions investigation that took place in those years. Compared with the other candidate’s voters, the Bolsonaro voters had a greater belief that they were fighting against corruption (80%), while those of Haddad were less convinced (56.2%) about this.

If we compare this data with the most recent polls, we conclude that, although there has been a general decrease in the president’s popularity, his support clusters are still congruent. When we detail this latest survey regarding social-demographic patterns, we observe that Bolsonaro continues to be more popular among men and inhabitants of Brazil’s south and southeast regions, especially among evangelicals. However, when we look at educational patterns, we observe that his popularity declines as the years of study increase.

This data can be framed by the analysis of Bolsonaro’s career as a federal deputy and by his years as president, both marked by the lack of priority for social issues, in terms of public policies for the most vulnerable groups of the population, even though, during the pandemic, the federal government implemented a programme of rent transfer to those that were living on the minimum wage. These policies allowed poor Brazilian citizens to survive during the most critical moments of the pandemic, since their income depended on informal jobs, mostly made impossible by social distancing. After the interruption of this financial assistance, distributed between April and December of 2020, there was a significant increase in poverty and extreme poverty.

The rising poverty did not become a source of instability for Bolsonaro’s government, nor his low popularity among the poorest, since political and economic elites guaranteed its stability. For this, religion, that is, its support among evangelical leaders, will not be enough.

Salvini’s people

On the 26th of May 2019, the League reached its highest voter support in elections: 34% of the votes at the election for the members of the European Parliament, and the second most voted-for party was the Democratic Party, with 22% of the votes. The League increased its average vote by almost six times in five years.

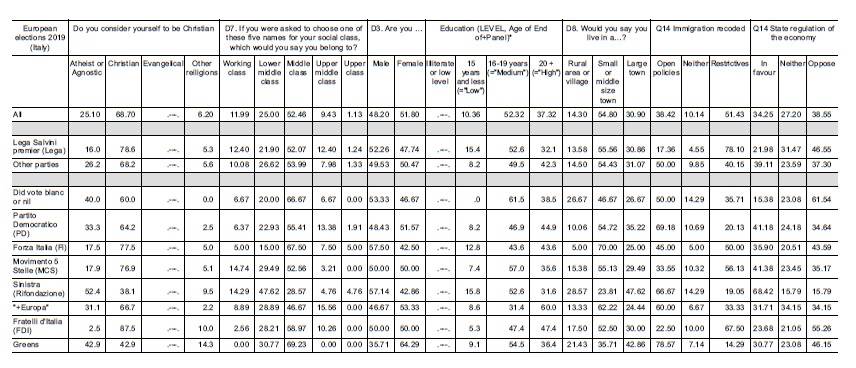

Who voted for the League in 2019? Or otherwise stated, how is the average League voter characterised? Alongside the Brazilian case, variables are divided into two groups: generic profile (religion, social class, male/female, education, rural area/city) and variables able to grasp the triggering factors analysed in the paragraph above: position toward immigration and state intervention in the economy). Table 2 shows data from a survey of the European Election Study (EES, 2019). The League’s voters present differences in several dimensions compared to the vote for other formations. The first, and certainly the most important, is the overwhelming percentage of voters who claim to have a sense of belonging to the Christian community (83%).

Table 2 League‘s Voters and their values - (All - League and others - Main parties ) - European election 2019

In contrast, among other parties, the percentage drops to 73%, a result that confirms how rightist populist parties attract more voters from those who consider themselves to be part of the Christian community. The second dimension is literacy. The average number of voters who claimed to have undertaken less than 15 years of studies was 15%, while the percentage among the other parties was significantly reduced (8%). This data also reveals the capacity of the League to attract voters from all social classes, that is, from the upper to the working class and of any range of educational levels.

In all other aspects, voters of the League and the other parties are similar: voters mainly live in small and medium-sized cities (54%-55%), to the middle class (52%-53%) and an almost equal male/female percentage of voters.

The second level of the triggering factors is clearly shown in table 2, demonstrating how vital the rejection of immigration is for the League’s voter (78% of them reject policies of integration) and how the League’s voter aims for a less interventional state in the economy: 46%.

Soon after the European elections, on 5th September 2019, a new government headed by the former prime minister was installed. It signalled the end of a crisis brought about by Salvini, at that time the Interior Minister, in the aftermath of the European elections (Adinolfi, 2022). The captain’s strategy was to capitalise on the highly positive wave of consensus around his leadership. Given the balance of the parties in the parliament, Salvini’s thought was that any other coalition able to support a government without the League was not possible. Without the League’s support and, given the distance between the 5 Stars Movement and the PD, the only way out for the head of state to solve the crisis was to schedule new legislative elections. On the verge of the outbreak of the governmental crises, the polls were firmly in favour of the League and, more broadly, for the coalition of rightist parties. In July 2019, the League’s support was 38%, Go Italy 6.5% and Brothers of Italy 6.6%. The sum of the three parties in the summer of 2019 was slightly above 50%, and the internal balance favoured Salvini’s party.

After this peak, Salvini’s leadership triggered the crisis and became evident after the local elections in October of 2021. There were two primary challengers: one internal, with two different Leagues wings, one favourable to a process of moderation and one external, for the leadership of the rightist coalition. Giorgia Meloni, the Brothers of Italy’s leader, completely eroded the support his contender had and, in the 2022 political election, Brothers of Italy garnered a 25% share of votes and the League 8%.

Conclusions

Italy and Brazil, Latin America and Europe: two completely different geographical scenarios united paradoxically by two similar figures: the Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, and the Italian League’s leader, Matteo Salvini. The two leaders share several points: long-standing political careers, weak parties, very conservative social values, and neo-liberal in the economic field. Although there are several common points between Italy and Brazil, there were also two different contexts that both produced the populist backslash and, therefore, there are two pathways to power. In the guise of operationalising a comparative analysis, we selected three different dimensions:

First: the leader. The main characteristic of a populist exercise of power is its leadership typology; this must be centralised and charismatic and not be connoted with a form of professional politics. In this dimension, we saw how, despite the differences, there are several points of continuity between the two leaders. Both leaders are nicknamed as captains, with a clear military connotation. Despite their longstanding political career in which neither Bolsonaro nor Salvini played an outstanding role in the political system at the moment of their appointment, they are not connoted as professional politicians. After the wave opened by the elections of Donald Trump, they suddenly became the pinnacle of the system of the equivalence chain within the conservative wings of public opinion. They both had very contradictory roles within their parties. In the case of Jair Bolsonaro, the party was never crucial, and he has changed many times. In the case of Matteo Salvini, he managed to undermine the Northern League by transforming it into an instrument to affirm his leadership. But both, through populist rhetoric, managed to revitalise small factions in transforming parties into those being able to win an electoral competition.

Second: the ideology. The equivalence of the chain of the two leaders is built around the Christian religion, but it is articulated in the two countries in different ways. The Bolsonaro people fought against corruption and the redistributive policies introduced during Lula’s era. It is a framework within religious values that connects all Brazilian citizens. In the Italian case, Salvini transformed the way the League’s discourse was taking from a regionalist to a nationalistic one, creating a nation where Christian values appear as the most critical unifying source, with a people that would fight against a secularised Europe; a people seeking its values in a sovereigntist vein fighting within the country against immigration. In these dimensions, the Brazilian and the Italian, the two people find the sources of the equivalence chain in Christian values. Still, they are different on the grounds of the sovereigntist obsession and the use of racial origins. In Salvini’s way of thinking, Christianism is a fundamental tool to unite the people against Muslim immigrants. In contrast, for Bolsonaro, it is an instrument against the alleged relativism of the leftist government.

Third: the audience. Despite being completely different environments, continents and countries, the question is: can we discern some thread of continuity between the vote for Salvini and Bolsonaro in establishing their chain of equivalences? Do they use the same empty signifiers? For the two cases, we selected similar dimensions - religion, social class, gender and literacy. The differences were fewer: in Italy, the gulf between rural areas and the cities, whereas in Brazil, it was the ethnic origins, being part of the Bolsa Familia’s programme and supporting the anti-corruption programme. Consistent with the ideology supported by the two leaders, in both cases, the electors of Bolsonaro and Salvini expressed a strong feeling of belonging to the Christian community (table 3). In Brazil, the divide is between Catholic and Evangelical; the latter voted more for Bolsonaro, 39.8% / 24.1%, and the former for the other candidates 47% / 56.8%). In Italy, despite the higher average of atheists or agnostics, the divide between religion/non-religion was more substantial. 78% of the League’s voters declared that they belonged to the Catholic community, while 68% voted for other candidates. Minor divides were the female/male voters, more substantial in the Brazilian case (55% male, 44% female) than in Italy (52% male, 47% female). The differences in social classes are vast, reflecting the differences between the two countries. Bolsonaro, in comparison with the vote for the other candidates, attracted his voters from the upper middle classes (21.2% / 11.8%), receiving the same average from the lower classes (19%). Some continuity was displayed in Italy, where Salvini is voted for, compared with other Italian parties, by the upper middle classes (12.4% / 7.9%) and the working class (12.4% / 10%). The central part of the vote came, in line with all the Italian parties, from the middle class (52% / 53%). The two triggering factors in Brazil were Operation Car Wash (Lava Jato) and the reaction coming from the upper classes to the Bolsa Familia’s programme. In Italy, the triggering factors were the waves of immigrants and the sharp increase in the imposition average introduced by the Monti government. The context in the two countries mobilised that part of the electorate in Brazil, which was not endowed with the Bolsa Famlia’s programme and was in favour of the anti-corruption trials, while that in Italy was vehemently opposed to immigration and state intervention.

The three dimensions, leadership, ideology and the audience, show, on the one hand, how the populist attitude helped in establishing the connection between the People and the Leader. The equivalence chain, based on the two countries in identifying between society’s values and the leader, unites a shapeless audience into a people. However, as explained by Laclau, this organic body that is the People is only an illusion, and it remains permanently unstable. The two leaders established a solitary leadership, founding new parties (as was the case of Salvini) or dominating weak parties (as in the case of Bolsonaro). The empty signifiers establishing their populist reaction was religion: Catholic for Salvini, evangelical for Bolsonaro. The victory was fuelled by some triggering factors that mobilised the voters. The factors relevant in establishing the equivalence chain, the Captains’ strength and charismatic leadership, however, became their weakness. Without solid systems of control of their power and their parties in confronting the pandemic crisis, they could not offer their supporters a constant mobilisation outside of the rhetorical discourse due to the lack of concrete results. Populism is not just a discourse; it is a complex political framework based on a discourse and an institutional arrangement, allowing for less intermediated representation. However, the outcome of the two leaders is very different. Salvini was defeated within the rightist populist field by a more effective leader, Giorgia Meloni, head of the government and her party Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d’Italia, FDI). Bolsonaro maintained his audience and lost the presidential elections in 2022, increasing the number of absolute voters.

To conclude, the ideological content of these discourses of Salvini and Bolsonaro can be appropriately typified as right populism according to Laclaunian characterisation, as they are structured from a dynamic of antagonism through symbols and actors considered enemies of the people. They both present a challenge to the political system since they focus their discursive performances and decisions on an ideology that is (i) morally conservative, (ii) economically orthodox and (iii) politically confrontational.