Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Etnográfica

versão impressa ISSN 0873-6561

Etnográfica v.14 n.1 Lisboa fev. 2010

Ethnography and public categories: the making of compatible agendas in contemporary anthropological practices

Susana de Matos Viegas

Instituto de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Lisboa (ICS-UL), Portugal ◊ smviegas@ics.ul.pt

Abstract

This article is a debate on research that deals with categories pre-defined in the public agenda. It is supported by an experience of doing an anthropological study for the Tupinambá of Olivença aimed at the identification of a juridical category of indigenous land defined by the 1988 Constitution of Brazil. The main argument developed in this article starts with the assumption that in the contemporary situation the definition of public categories that involves cultural and social rights of minorities, such as terra indígena, have been defined in public debates in which anthropologists were involved. One of the necessary results of such a situation is that anthropology cannot see these categories as exogenous concepts to be criticized, but as categories of knowledge to be addressed. A detailed proposition of how I have addressed the issue concerning the delimitation of the seacoast border of the indigenous land of the Tupinambá of Olivença is here developed, showing how ethnography in anthropology is a particularly good device to achieve this challenges. Through the Tupinambá case, it is showed how ethnography as situated knowledge, enmeshed in a comparative project and prepared to incorporate the struggles that people face when dealing with conflict situations, intertwines public and indigenous definitions of social categories (in this case, the land) through what is here named compatible agendas.

KEYWORDS: ethnography and advocacy, indigenous human rights, landscape and sociality, indigenous land, Brazil, Americanist debates.

Etnografia e categorias públicas: agendas compatíveis na prática antropológica contemporânea

Resumo

Neste artigo proponho uma forma de a antropologia lidar com investigação sobre categorias de conhecimento que foram definidas previamente na agenda pública. A reflexão sustenta-se na experiência de realizar um estudo antropológico a pedido dos índios tupinambá de Olivença, sob contratação do governo brasileiro, com o objectivo da delimitação de uma área de território definida na Constituição Brasileira como terra indígena. O argumento desenvolvido neste artigo parte da ideia de que a definição pública de categorias como a terra indígena já não é prévia à antropologia, na medida em que, na situação contemporânea, a definição do que é e como se define a terra indígena resulta de um longo debate público no qual a antropologia esteve directamente envolvida. Sendo assim, a antropologia é necessariamente responsável por encontrar um enfoque ajustado que não passe por considerar tais definições como objectos exógenos. A produção actual de etnografia como conhecimento situado oferece condições muito ajustadas para este enfoque, já que permite entrelaçar definições indígenas e públicas de categorias sociais (neste caso, a terra) que alcancem agendas compatíveis. A etnografia como conhecimento situado é aqui apresentada como um projecto de conhecimento empírico e comparativo, capaz de incorporar a luta e conflitos implicados em processos como os da restituição de direitos sobre a terra.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: antropologia e intervenção social, etnografia, socialidade e espaço, direitos humanos indígenas, Brasil, debates americanistas.

This article is an anthropological debate on the contemporary conditions for anthropologists to deal, as researchers, with the study of categories pre-constructed in the public arena.[1] Instead of underlying a radical distance between advocacy anthropology and academic anthropology, the reflection is here developed from two different assumptions. First, that anthropology cannot but be considered a discipline historically enmeshed in the construction of public categories. In this sense, dealing with categories pre-defined in the public arena means in most cases dealing with ideas and concepts to which anthropological action or thinking has somehow contributed. Secondly, the article argues that ethnography is particularly suitable to produce knowledge in situations where we are dealing with public categories, with conflict and the crisscross of diverse agendas, because it produces situated knowledge, that is, it is capable of incorporating both the changing of perspectives resulting from events, different voices and points of view and a broader sense of the world and its meaning in a larger comparative debate. It thus suits the need to incorporate different levels of knowledge that become a possible truth in conflict situations. In this article such a condition of ethnography is highlighted for its advantages of doing academic ethnography as a way of dealing with public processes.

The argument will be here developed following the procedures that I have adopted for the anthropological study for the identification of indigenous land (terra indígena) for the Tupinambá of Olivença – a category defined by the 1988 Federal Constitution of Brazil.[2] This experience can be considered of a larger interest. The definition of indigenous land as a public category has been constructed through a successful debate between indigenous people, anthropologists, jurists and others involved in the defence of indigenous rights. This process resulted in the approval of the 1988 Constitution of Brazil, significantly in the period of democratization. In the 1990s the discussion has enlarged to the international arena. The international legislation approved by the General Assembly of the United Nations in September 2007 – Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (DRIP) – resulting from a decade of debate among indigenous people at the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, states that: Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired (United Nations 2007, Article 26, my italics).[3] In the Brazilian Constitution, indigenous land is defined as a land traditionally occupied by Indians, linking cultural, social and environmental arguments in terms of the occupation of that territory. The similarities of both definitions should be thus highlighted and may help to consider the importance of the Brazilian experience.

Since 1988, Indigenous land claims in Brazil have been conducted by the Brazilian government through administrative and juridical procedures. The identificação (literally identification) is the first phase of government recognition of the rights of indigenous people to their lands. Academic anthropologists became engaged in this phase that precedes the juridical contestations, mainly because of their expertise in fieldwork experience with a particular people and region. In fact, the anthropological study for the identification of indigenous land is conceived, first of all, as the study of the area that indigenous people claim to be their territory and the construction of an ethnographical argument based on the requirements of the Constitution. This phase in the recognition of an indigenous land is followed by four government and juridical phases in which anthropologists do not participate (cf. Gonçalves 1994: 85; Mendes 2002: 17; Lima e Barreto Filho 2005: 10).[4] In this respect, the role of anthropology in indigenous land claims in Brazil is substantially different from, for instance, indigenous land claims in Canada where the anthropologist is considered more as an expert witness in the juridical process than as an expert fieldworker and ethnographer (cf. Oliveira 2002; Santos 1995; Hedican 2000: 68-73).

The identification process is conceived as collaboration between indigenous people and the anthropologist. This relationship involves a great deal of negotiation at different levels and phases of research. But the situation is not unfamiliar to those involved in contemporary conditions of research in the indigenous context in South America, where anthropologists are constantly called to intervene in public issues (cf. Albert 1997; Jackson 1999: 284; Oliveira 2002: 253; Ramos 2003: 110-111; Freire 2003; ODwyer 2005: 217). As Bruce Albert argued a decade ago:

Combining ethnographic research with advocacy work has thus become the basic fieldwork situation for many anthropologists in countries where indigenous people have emerged as important political actors, as in Australia, Brazil or Canada (Albert 1997: 58).

The anthropological research required for the identification of an indigenous land can thus be envisaged as an exemplary situation to consider this intertwined relation of ethnography and advocacy practice. Although the questions I want to raise are not directly related to the debate on advocacy and anthropology (cf. Sillitoe 2006: 13), I will progressively get to that issue. On many levels what happens in this situation exemplifies a frequent condition in contemporary research. As a result of the history of intervention of the social sciences in the public sphere, many categories are now defined in the public arena with the participation of both anthropology and indigenous people.

This commitment of the social sciences in the history of the construction of public categories constitutes a kind of synergy that confronts anthropologists more deeply with their social responsibility, bringing to light three important issues for debate. First, the possibility that indigenous voices substitute the voice of the anthropologist. In this respect I would agree with Jean Jackson when she argues that anthropologists are indeed entitled to speak about them [indigenous people] although as she considers, this may bring serious ethic and emotional dilemmas when they are engaged in fieldwork in a politically charged and rapidly changing site (Jackson 1999: 283). Moreover, indigenous people recognize the voice of anthropology as legitimate (e. g. Jackson 1999; Santilli 2001: 124).

Secondly, we must consider if ethnography is a kind of knowledge particularly suited to conditions where negotiation of meanings and political debates are at stake. I will argue in this article that, taken as situated knowledge, ethnography helps us to deal with processes where the fight for new rights and political organization is the issue, as is the case in land rights claims in Brazil. This is because ethnography takes into account how people live in the world and helps us to understand this experience in a larger context of comparable meanings. Further, it incorporates the political and social processes that may occur during the fieldwork research, even when they result from the relationship between the anthropologist and the people we study.

A final issue to be considered is how anthropology deals with a situation in which the ethnographer is, simultaneously, the observer and the subject of multiple conflicts of interest, being positioned as a mediator. In this respect, I follow Bruno Latours (2002) inspiring proposal that to assume a common denominator prior to social and cultural relations has never been helpful in finding satisfying solutions for mediating agendas based on difference and inequalities. It is preferable to accept that perspectives, attitudes and conceptions of the world are intrinsically conflicting. They are, in Latours words, at war. From this point of view, the identification of indigenous land becomes a permanent endeavour of constantly seeking peace, in ways that necessarily imply exchanging meanings, experiences and observations with people in the field and then trying to establish a mediation in which the anthropological agenda of doing ethnography is also included. I will call this a way of looking for compatible agendas, in which we must be prepared to make compatible what at first sight would seem to be misunderstandings (Pina-Cabral 1999; Viegas 2007: 237-274; Viveiros de Castro in press).

Latour uses the figure of the diplomatic work for the description of this process, in the sense that diplomats know that if a solution is to be found it arises from negotiation, among the people, with them here and now (Latour 2002: 37-38). Thus, I follow the idea that in the identification of indigenous land, the anthropologist must also use fieldwork skills as diplomatic work, in order to find a position in which ethnography is at the forefront.

THE PRE-DEFINITION OF INDIGENOUS LAND

As situated knowledge, ethnographical approaches start by taking into account how a category such as indigenous land has been constructed and what the role is of the social scientist and indigenous leaders in that history. The legal rights derived from the definition of indigenous land rely on cultural diversity, articulating original, immemorial, but mostly consuetudinary rights.[5] Article 231 of the Constitution of Brazil defines indigenous land as traditionally occupied by Indians:

The Indians [Os índios][6] shall have their social organization, customs, languages, creeds and traditions recognized, as well as their original rights to the lands they traditionally occupy, it being incumbent upon the Union to demarcate them, protect and ensure respect for all of their property (cit. in Magalhães 2003a: 29).

In the context of South America, this article is considered as pioneering the recognition of indigenous land rights. Although in countries like Venezuela, Colombia or Peru special rights have been recognized for indigenous people, until 1988 they were not recognized at such a high level of legislation as the Constitution. In Colombia only the 1991 Constitution integrated a similar recognition (Ramos 2002: 260) and in Venezuela this came about only in 1999 (cf. Freire 2003).

This achievement of the Brazilian Constitution has been already evaluated as a result of multiple historical situations. One is indigenous mobilization on a global scale, that began in the 1970s mostly in Canada (Ramos 2002: 253), or the post-colonial situation on the international scene. On a national level, as mentioned above, a very important issue to take into account is the democratization of Brazil, a country that had a series of dictatorial regimes between 1937 and 1985, the most repressive being the military dictatorship between 1968 and 1985 (cf. Santos 1995: 87). The intervention of the national organization of indigenous people in Brazil, the Union of Indigenous Nations (União das Nações Indígenas), founded in 1981, was also one of the most significant achievements for indigenous people in this period. At the same time, indigenous leaders, such as Mario Juruna of the Xavante and Payakã of the Kayapó, gained notoriety on an international level (cf. Conklin and Graham 1995: 699-701). These and other significant achievements of the indigenous social and political movements explain how indigenous people were able to participate directly in the constitutional assembly that took place in Brasilia in 1988 (Ramos 1998: 19). In the course of discussing indigenous rights, they also made important alliances with different branches of intellectuals, from jurists to anthropologists.

Brazilian anthropologists have been largely involved in the debate on indigenous rights through different associations, from NGOs to ABA, the Brazilian Association of Anthropology (Agier and Carvalho 1994: 107; Santos 1995: 87; Ramos 1998: 19).[7] This is why when we deal with the category of indigenous land, meaning land traditionally occupied by Indians, we must take into account the fact that for the most part it is a category coined by indigenous people and anthropologists. Moreover, the involvement of both anthropologists and jurists did not stop in 1988. On the contrary, various important discussions ensued, namely in terms of what is meant by the traditional and permanent occupation of a land, as these are the main terms for the identification of a specific territory as indigenous land.

The Constitution establishes that a land is traditionally occupied by Indians when the following four principles occur simultaneously: a) areas inhabited by the indigenous group on a permanent basis; b) areas used by them for productive activities; c) areas that are essential for the preservation of environmental resources necessary to their well-being; d) areas needed for their physical and cultural reproduction, according to their usages, customs and traditions (Article 231, §1, cit. in Magalhães 2003a: 29).

These principles indicate a turning point in indigenous politics in Brazil formerly based on territorial reservations. The ideology involved in indigenous reservations was based on the long-term modern project of the civilization of indigenous people. Being conceived as areas to gather and control indigenous people who were living scattered throughout the territory, and to help their civilizing process, indigenous reservations were pieces of land defined through administrative and political interests, independently of the will of the people concerned or difference in indigenous ways of living (cf. Lima 1995: 288). One of the destructive results of such politics for indigenous people in Brazil, and in many other countries in other parts of the world, is the fact that, first, the location and frontiers of such reservations are defined by interests foreign to indigenous people, such as governmental or capitalistic interests, very similar to those adopted, for instance, by the colonial countries of Europe when they divided the African continent in the 19th century. Secondly, history has shown us that the areas for indigenous people defined in this way were undersized. Because they have never been thought of as real spaces to be inhabited, they did not allow indigenous people to survive there. In Venezuela, reservations were submitted to the Agrarian Reform Law in the 1960s and thus atomized and restricted [indigenous] possession, ignoring basic aspects of their land use practices (Freire 2003: 355).

Contrary to this legislation and policy, the definition of indigenous land on the basis of traditional occupation recognizes that landscape is a sociocultural entity and not an extension of terrain measured by demography or agricultural needs. In one of the important publications that resulted from the debate between anthropologists and jurists after the 1988 Constitution of Brazil, a jurist from the Public Federal Ministry argued, quoting anthropologists, that traditional means that indigenous people have a sociocultural relationship to the landscape, and that it is this relationship that needs to be described and mapped if land is to be regarded as traditionally occupied by Indians (Gonçalves 1994: 83). Gonçalves further establishes that the traditional occupation must be considered from the contemporary situation of life: the past is only considered as a time reckoning of a long-term inhabitation of the area, and the future is considered as a measure of the physical and cultural reproduction, which means calculating the area of land indigenous people need in order to maintain their well-being in the future (cf. Gonçalves 1994: 83).

The first alliance of anthropology and the public sphere after 1988 arose from the relationship between the Brazilian Association of Anthropology and the Attorney General (Procuradoria Geral da República), at the beginning of the 1990s, when the Procuradoria had to reply to lawsuits of landowners. They concluded that only anthropologists would do sufficiently qualified work that could prevent the Federal State from losing these juridical cases (Oliveira 2002: 255). When faced with the international spotlight on Brazil that came with Eco 92 (the second Conference of the United Nations for the environment and sustainability) the first important demarcation of indigenous land occurred effectively sustained by anthropological knowledge (Oliveira 2002: 256). Indigenous social movements attracted international financial support, which allowed several projects connected with the demarcation of indigenous land in Amazonia in the 1990s to be carried out.[8]

From 1995 onwards, the collaboration of anthropologists in these processes became more explicit to the point of being legislated (cf. Oliveira 2002: 253). In 1996 (under the government of President Fernando Henrique Cardoso), the four principles of the above-mentioned Article 231 of the Constitution were multiplied in terms of requirements for the anthropological study for the identification of the indigenous land. These requirements are strongly based on detailed ethnographical description of indigenous social, political, and economic life, just as much as their use of natural resources, sense of belonging to the landscape and symbolic meanings of space and nature.[9]

TWO TYPES OF FIELDWORK

As outlined above, the debate in this paper is rooted in my experience of being the coordinator of research for the identification of the indigenous land of the Tupinambá of Olivença (south of Bahia). This research was conducted in 2003-2008 and was a result of a contract with UNESCO and Funai (National Indian Foundation – the department of the Brazilian Ministry of Justice that deals with indigenous affairs) at the request of the Tupinambá of Olivença.

The previous fieldwork experience I had amongst the Tupinambá of Olivença involved one continuous year of fieldwork in 1997-1998 supplemented by shorter periods of one month in 1999 and 2000 (cf. Viegas 2007: 20-23). This first type of fieldwork loosely involved what various anthropologists have called the anthropology of daily life (cf. Gow 1991; Carsten 1995, 2000: 18; McCallum 2001; Overing and Passes 2000: 8-10; Harris 2000: 19; Viegas 2007: 37-42). I thus cohabited with an Indian family and based my participant observation in one of the localities where the Tupinambá live (Sapucaeira), investing mostly in fieldnotes of everyday life, and carrying out only a few interviews with people in several areas of the territory. During this period I also came into contact with indigenous social movements in the nearby town of Ilhéus, and I participated in several regional meetings of indigenous people in the south of Bahia.[10]

As the coordinator of the research for the identification of the indigenous land in 2003-2008, a completely different fieldwork situation arose. First of all, this fieldwork is official, which means that, for instance, a government act is published giving the exact time the anthropologists will arrive and leave the region of fieldwork; and secondly, until the research is submitted, the anthropologists cannot visit the area nor carry out fieldwork without the knowledge and permission of Funai, who must send a person to accompany them during any visit they might choose to make. Consequently, the periods of fieldwork are short, on average around one month, and extremely controlled. A final important specific requirement of the fieldwork is the constitution of a multidisciplinary team with an environmentalist and a skilled topographer – making a GPS [Global Positioning System] survey of pathways, rivers and, above all, places where Indians live.[11]

The area we studied is around 50.000 hectares in a region of Atlantic forest. I then had to drew up a plan for extensive research (that seemed more like fieldwork in the form of expeditions), with the aim of getting to know as many units of indigenous residential compounds as possible. Although it has been partly deforested, the roads that connect the whole territory are dirt tracks and sometimes seriously damaged or nonexistent. But in the end we have been able to visit around 70 indigenous residential compounds (taking in a total of 220 houses), which the Tupinambá of Olivença call lugares (literally places) in seven different localities. We mapped the houses and gardens, conducting semi-structured interviews and a genealogical survey. We also visited other houses that are not aggregated in residential compounds, making a total of around 300 houses visited, covering almost the entire population of the Tupinambá of Olivença. I taped around sixty hours of conversation, following semi-structured guidelines. The outline for the interviews arose from the issues I had already debated in the ethnography that resulted from the first type of academic fieldwork (Viegas 2007), such as: ways of giving meaning to inhabited space and landscape, life histories, ways of becoming kin and of making sociality.

The involvement of indigenous people in the research was fundamental and should be considered in different ways. I witnessed the increasingly growing enthusiasm of the Tupinambá of Olivença during the years of 2003-2008 while the study for the identification of indigenous land was proceeding. The expressions of that enthusiasm were of different kinds, from the most subjective – like the increasingly frequent occasions for laughter and talking in meetings, the fluency of conversations and a general expression of hope – to the more measurable, such as the growing number of participants in meetings (from an average of twenty in 2003 to seventy in 2008). During the fieldwork for Funai, leaders of the Tupinambá of Olivença in different political positions collaborated closely with me. The official leader (liderança) who represents the Tupinambá for Funai, named cacique, was elected to that position in 2001. The cacique elected was a woman who lived in the town of Olivença. She filled the role of mediator between the highly bureaucratic and political relationships of the federal government departments for indigenous affairs, and the community – a role of mediation that characterizes this type of late twentieth century Latin American indigenous leadership (cf. Brown 1993: 311).[12]

The fieldwork was also carried out in close collaboration with local leaders, such as agentes de saúde (health agents). In order to get indigenous health assistance from the government, the Tupinambá of Olivença also divided their territory into twenty two communities. In each community there is a person responsible for health affairs, officially named health agent (agente de saúde) by the governmental agency Funasa. They are responsible for calling Funasa to attend people who fall sick in the community they represent or for taking people directly to the Funasa post in the nearby city. The Tupinambá thus consider these local agents as a kind of local leaders. During the fieldwork process for the identification of the indigenous land they fully assumed that role. Local leaders (agentes de saúde) helped us as fieldwork assistants, collecting data in places we did not have time to visit. They were also usually chosen by the cacique to guide us to the houses of indigenous people in the different localities we visited and so we kept up a lively continuous relationship with them throughout the whole process of fieldwork.

The cacique had a continuous and double role in the process. First, we had daily debates on how the work was being conducted and that, taking into account the legislation on indigenous land, I might need to propose a reduction of the area previously considered by them as indigenous territory. Sharing the daily experience of travelling on such damaged roads somehow aided these open debates and understanding each others points of view. These dialogues and exchanges of ideas became part of my fieldwork material. The fact that I already knew some of these leaders and that they had confidence in my work, was of the utmost importance in making this kind of collaboration possible. Our mutual understanding and mutual confidence enabled these leaders to both gain a deeper understanding of the complex demands of the indigenous land legislation and, as mediators, to discuss contentious subjects, such as the need to reconsider the limits of the land, with other indigenous people and later with the government agencies.

The involvement of the Tupinambá in this research was not, of course, only restricted to the leaders. As I mentioned above, we visited the Tupinambá in their homes, and they were so grateful for our presence that they would, in general, talk with enthusiasm on any subject of enquiry. This was particularly astonishing to me, because my previous experience of fieldwork revealed shyness in interaction and, at the beginning, an attitude of distrust (cf. Viegas 2007: 183-188). The leaders were extremely sensitive to the necessity of not interfering with these interviews. We would only exchange ideas and opinions about the Indians situation after leaving from each visit to the residential compounds.

Besides this daily work, the collaboration with the Tupinambá also resulted from meetings we organized. Indigenous people from the different localities of the territory came to these meetings to listen to us and discuss the preliminary results of the research, mainly in terms of the limits of the land. Theoretically, these meetings should have gathered together local leaders from each community of the territory. But the fact that this type of representation did not yet constitute an effective means of political organization was by then becoming clear. People would come to the meetings representing their own residential compound, following the former political organization strongly based on the autonomy of these social units (cf. Viegas 2007: 112-117, 173-175, 208-212).

Three months after delivering the four-hundred-page anthropological study for the identification of the Tupinambá of Olivença indigenous land to Funai, in July 2005, Funai asked me to go back to fieldwork with only a Funai administrative. I realized that the idea was to present the map to the Tupinambá and confirm, with the testimony of an official representant of the Department of Land Affairs in Funai (Brasília), that the Tupinambá did in fact approve my work. This representant of Funai was there to record the meetings and draw up a report for the indigenous people to sign, approving the results that had been presented to them. This final process, which I will address in the section preceding the closing remarks, constituted the highest point of tension, where the description of the position of the anthropologist as someone who is not defending the Indians against Funai nor mediating their relationship, but is on her own, trying to achieve compatible agendas, is depicted with crystal-like clarity.

AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF TRADITIONAL OCCUPATION: THE MANGROVE AND THE SEACOAST

It is of general consensus that the most important aspect of indigenous human rights in the contemporary world is the recognition of the limits of an indigenous territory in accordance with the way indigenous people use it – as defined by the concept of traditional occupation (cf. Baines 1997: 2; Oliveira 2002: 265). In this section I will address the argument on traditional occupation from the point of view of the recognition of the coastal border of the indigenous land as land traditionally occupied by the Tupinambá.

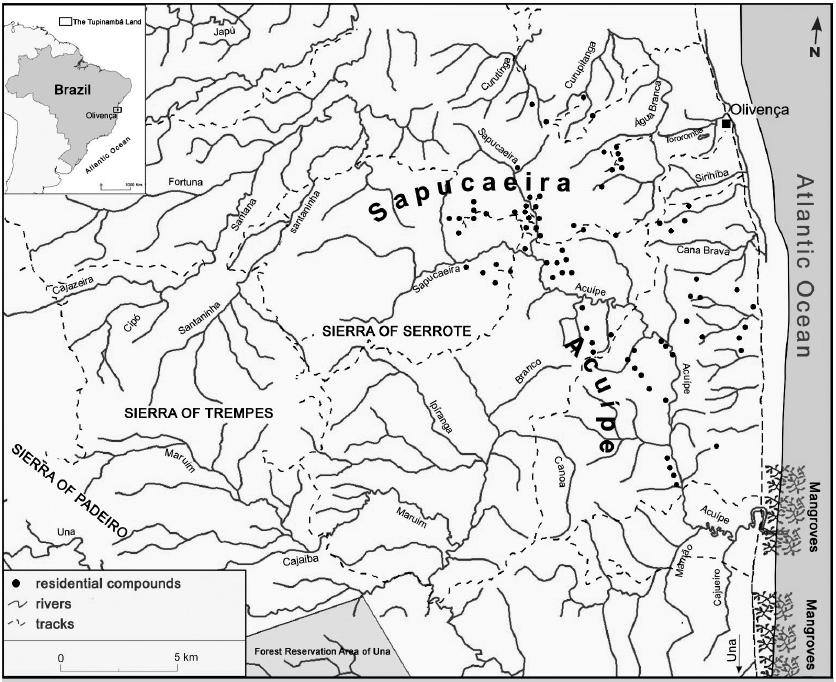

The area claimed by the Tupinambá in 2003 covered approximately 50.000 hectares, between a strip of coastline of about 17 kilometres in length and a mountainous region (see figure 1). This territory is inhabited by roughly 3,000 Tupinambá, 50 tradesmen, ranchers and tourist-resort owners and about 10,000 peasants, having considerable differences in terms of natural resources. For instance, in each of the localities they make use of specific water and forest resources that constitute their social meaning of space: some small rivers are mainly used to provide water for houses and occasionally for fishing outside the area of each residential compound, while in other branches of the territory houses are located closer to deeper rivers where fishing techniques are more sophisticated and differentiated from other areas.

In the whole territory, the Tupinambá do not live isolated from their non-indigenous neighbours either in demographic terms or in sociability habits. However, they do live and make residential arrangements differently from their migrant neighbours, inhabiting small compounds consisting of several houses of an extended family. Compounds, as mentioned above, are locally known as lugares (literally places) and each lugar is known by the name of its founder. This is usually the husband, but it could also be the wife, of the first couple to establish the compound. Each compound is located close to a stream, which is used on a communal basis by all of its inhabitants. Each compound comprises from one to six buildings, the number of which is constantly changing due to various significant reasons. One is that buildings are viewed as ephemeral structures to be destroyed and rebuilt in short periods of time; another is that death often functions as an invitation to abandon a building (cf. Viegas 2007: 212-225). Despite their eventual mobility, however, residential compounds have a definite effect on the way parent-child links are established. One of these consequences is the intimate relationship established between a child and the kinswomen on the fathers side who inhabit the same compound (cf. Viegas 2003). The autonomy of each residential compound is thus at the centre of sociality among the Tupinambá of Olivença. As we will see later, this is of the utmost importance to the significance of spaces that are used by the Tupinambá of Olivença living in the total of 70 residential compounds spread out in the 50.000 hectares of land (see also Viegas 2009).

The argument over the coastline was one of the most problematic issues in the process of the identification of the indigenous land of the Tupinambá of Olivença. Not only because the seacoast of Olivença is an attractive touristic area, with all kinds of tourism facilities – from hotels and resorts to urban blocks of apartments aimed at attracting people from the nearby town of Ilhéus – but also because the Atlantic is a geographical border of Brazil, under the jurisdiction of the military seacoast police. The official map of my proposal for the limits of the indigenous land of the Tupinambá of Olivença only considers the inclusion of around five kilometres of seacoast, but to include even this comparatively reduced area I had to make a strong argument (cf Viegas, Melo and Paula 2009). The possibility of juridical contestation is particularly high when more powerful economic and political interests are involved and in order to avoid this it is particularly important to rely on the consistency of the ethnographical argument in accordance to the Constitution. But at the same time my final decision on the reduction of the area on the seacoast also resulted from constant conversations on the issue, particularly with indigenous leaders, and in the meetings. The meetings were particularly good occasions for debate and negotiation because they usually involved staying together for two or three days, eating together, sharing the floor to sleep, chatting at night, having a bath together in the river and so on and so forth.

In order to justify any part of the seacoast that the Tupinambá claimed, in accordance to the Constitution, a central issue is to understand in what ways it is an area used by the Tupinambá in their contemporary way of life, and in what ways it may be indispensable when thinking of their survival in the future (an issue defined in lines c) and d) of Article 231 – see above). From my previous fieldwork I had no idea about the sociocultural relevance of the coast for the Tupinambá of Olivença. I knew that one of the seasonal activities of people living in the village was to sell artefacts on the beach. I also knew some people even from inland would occasionally come to fish on the coast, but I had no concrete data about it.

The fieldwork inquiries developed in 2003 and 2004 revealed that actually there were no fishing communities among the Tupinambá. Differently from other non-indigenous people living in the village, none of the Tupinambá would consider himself a fisherman. Moreover, I began to realize that the Tupinambá did not like sailing far away from the coast either. The use of rafts (jangadas) that the Tupinambá sometimes refer to as a symbol of their way of living in a traditional way is an indicator of this, because jangadas are meant to sail in calm water and the sea in Olivença is rough.

My conversations with the Tupinambá, when visiting their homes, also confirmed that the fishing activity of the Tupinambá is seasonal and of a specific type. At the same time I came to the conclusion that, for reasons related to their fishing techniques, they very often fish at a specific site in a rocky area that juts out into the sea. I had heard about this area many times since my first year of fieldwork in 1997. In 2003 I was guided to visit it by two men who live nearby. We made a GPS point there so that I could mark it on the map as a symbolic area – a category considered in the legislation for the indigenous land. Memories of old people also made reference to how in the past the Tupinambá would fish from that rock and that the beach was a meeting point for the Tupinambá to exchange fish for other consumables.

I used this symbolic reference in order to argue that the indigenous land should at least guarantee the access of the Tupinambá to this area. In 2003 this access was a problem for the Tupinambá living in the nearby locality. The construction of a fence and the vigilance of a closed condominium forced indigenous people to walk more than one kilometre by the beach to get to this fishing point. Although the actions performed by the owners of the closed condominium were illegal (because they cannot legally block access to the beach), this is a frequent practice in Brazil that exemplifies why it is important for indigenous people to have power over the use of the land where they live.

The most important argument to identify part of the seacoast as indigenous land resulted, however, from a much broader ethnographical reflection, related to the meaning of an area of mangrove to the south of the village. In my first ethnography and fieldwork I had not paid much attention to the importance of the mangroves to the Tupinambá. One of the reasons for this was the fact that its importance could only be totally revealed by more extensive research. Since 2003 I had heard several descriptions of the limits of the Tupinambá territory in which rivers, mountains and mangroves would be the geographical points. In one of the meetings, I organized a kind of workshop, in which I asked the Tupinambá who inhabited different localities to discuss and draw up a map indicating the limits of the territory they claimed to be indigenous land. I observed then that rivers were used to mark the limits of the territory, but most importantly to this argument that the limits of the seacoast in these drawings always included mangroves.

From the conversations with the Tupinambá in their homes, and in visits we made specifically to the mangrove area, I began to understand the importance of the mangroves as part of the sociality of the Tupinambá and relate it to my previous ethnography. Although the mangrove is next to the sea and far away from most of the areas where the Tupinambá live, they all love to collect crabs seasonally in the mangrove, irrespective of the area or ecosystem of the territory they usually live in. The Tupinambá who inhabit areas near the seacoast go on foot and come back home after a whole day collecting crabs. Indigenous people living inland organize trips to collect crabs in the mangrove among the inhabitants of each Tupinambá residential compound. In the past they used to go to the mangrove seacoast area by mule, but now they usually join up with neighbours and go by car. When they get there, however, they divide again into groups of the same residential dwelling.

The descriptions I heard of the joy and happiness of their stay in improvised houses, made of plant leaves, for five days eating crabs, day after day, in the mangrove area, is particularly meaningful when we realize that the area of the mangroves is usually dark, because the vegetation is intertwined and low, that the clay is humid and in general the activity of collecting crabs is considered physically demanding. Crabs are caught no more than four times a year in the mangrove, at the time of year when the crabs come out of their hiding places in the earth, and walk about on land. The Tupinambá of Olivença call this the crab-walking period (andada do caranguejo) or the date of the crabs (a data do caranguejo). Moreover, when the Tupinambá manage to catch a large amount of crabs (I heard people mention numbers of around one hundred and even five hundred), these are shared not only between relatives of the same dwelling unit, but also between relatives in other neighbouring dwelling areas. People clearly mention that they offer some of the crabs they collected to their neighbours who did not go to the mangrove.

In sum, crabs are shared among an unusually wide circle of relatives, making important social bonds in a context otherwise strongly marked by the autonomy of the house, the dwelling units and local groups (cf. Viegas 2007: 208-212, Viegas 2009). The amount of crabs to be collected is usually even greater than that needed for consuming and offering to neighbours. I heard reports of people eating crabs for five days in a row while watching the crabs, unable to survive five days out of the mangrove, die in front of them. The Tupinambá do not seem to have, and more importantly do not seem to be interested in finding, a way of keeping the crabs alive or fresh. This is exactly because crab eating is marked by excess and even by waste. Eating crabs is thus not only a way of establishing solidarity ties but also related to abundance and excess.

In order to understand the social and cultural meaning of this practice, the reference to the previous ethnographical understanding of social life among the Tupinambá was of the utmost importance, revealing how ethnography as contextualized and comparative thought could be useful in the identification of indigenous land. This can be referred to here in relation to two aspects: first of all, the meaning of the residential compounds and their autonomy; secondly, the importance of acts of eating and of pursuing and preparing food that is particularly pleasurable for the Tupinambá of Olivença. I have developed these arguments in the context of an ethnographic and comparative argument that aims at a broader ethnographical perspective (Viegas 2003, 2006, 2007, 2009), concerning Amerindian socialities and their different ways of emphasizing, on the one hand, the centrality of the body and eating practices on the construction of the person, and, on the other hand, the meaning of the autonomy of small residential dwelling units.

In my previous ethnography I addressed the emotional power entailed in the intertwining of what is eaten and the pleasure derived from eating certain food, with feelings of belonging among the Tupinambá, expressed in the care for children in the construction of kinship and of an indigenous body and person (Viegas 2006, 2007: 73-142). I showed that certain food that the Tupinambá eat, such as manioc-based food, makes their bodies different, because it carries special meanings concerning their identity (Viegas 2006). At the same time, kin links are seen as relationships that need to be constantly reiterated by daily feeding and being cared for (Viegas 2003).

The Americanist debate on how socialities are meaningful in terms of bodily dynamics and personhood is therefore of particular importance (Seeger, Viveiros de Castro and DaMatta 1979; Viveiros de Castro 1998; see also Gow 1989, 1991; Vilaça 1998, 2005; Conklin 1995; Turner 1995; Fausto 2007), not only in terms of commensality (the act of sharing food) but also because people become the same through acts of being made and / or transformed through the sharing of a food code, i.e. what one eats (Rival 1998: 621; Vilaça 2005: 446; Fausto 2007). Commensality occurs when the definition of kin is based on ideas of their being my co-eaters, as is the case for the Yanomami Sanumá (Ramos 1995: 43) or when belonging to a sib depends on sharing food, as among the Cubeo (cf. Goldman 2004: 142). Numerous examples exist, not only in South Amerindian contexts but in many other parts of the world, in which social solidarity is to a great extent based on food and / or culinary mediation, and can even be considered a kind of extensive common denominator of what it is to be human.[13]

Different to commensality, though complementary, is the second aspect mentioned above – what one eats. This stresses a specific preference for certain foods as a strong indicator of difference in bodies and personhood. These are ways of producing related bodies through sharing food and a culinary code [that] make [...] people of the same kind (Fausto 2007: 502). I have already highlighted in other articles how emotions and affection involved in acts of caring / giving food are constitutive of a temporality for kin ties and, in the case of manioc-based food are deeply intertwined with feelings of belonging to a specific landscape where manioc grows (Viegas 2003, 2006).

The second aspect of this broader understanding of sociality among the Tupinambá is the importance of the autonomy of the residential dwellings that the practice of collecting crabs reinforces so well. In the Americanist debate Peter Rivière (1984) once called this the Amerindian individualism, considering this autonomy in different manners, depending on the context: from a kind of social philosophy in which the idea of living in larger and communal groups and being represented on a higher level than these small groups of relatives does not make sense, to being a way of avoiding conflicts. In an important argument about the indigenous land of the Makuxi, the anthropologist Paulo Santilli also argues the importance of the autonomy of small groups of relatives among the Makuxi when considering indigenous land, because it is a structural factor of social organization (Santilli 2001: 87).

The occupation of the territory by the Tupinambá of Olivença in separate and autonomous residential dwellings must then be considered as part of their historical way of living. In 1997-1998, when the indigenous movement in Olivença was just beginning (cf. Viegas 2007: 15-27), indigenous people did not show much interest in knowing their relatives living in different localities (not that far away from where they lived). Indigenous people living in different localities did not frequently visit each other, except when a marriage between a man and a woman from different and distant localities occurred and people kept relationships between affines.

The political process of identifying indigenous land confirmed the importance of this economic, political and social way of living in separate residential dwellings, shaping a sense of general validity of this principle of sociality (cf. Viegas 2009). As I already mentioned in the former section, in the meetings to discuss the results of the fieldwork in 2003-2004, instead of being represented by the leaders of each community, the Tupinambá of Olivença would not consider that one leader from a community could actually represent them or the community. The significant social units still were the residential compounds.

In sum, in order to argue in favour of the identification / inclusion of an area of seacoast as indigenous land of the Tupinambá of Olivença, I sustained the ethnographic argument incorporating my previous ethnographic knowledge and comparative perspective, and the fieldwork experiments and social processes that were occurring during this period. I thus discussed this material in constant negotiation, throughout events occurring during the process of fieldwork for the identification of the indigenous land.

NEGOTIATION AND THE ACHIEVEMENT OF A COMPATIBLE AGENDA

In 2005, two months after delivering the first draft of the anthropological study to the Department of Indigenous Land Affairs (Funai), I had to present a draft version of the map to both the Tupinambá and to Funai in order to get their approval. In the meetings among the Tupinambá I had to face expectations regarding the outline of the borders and again the issue of the seacoast borders was discussed. Despite the previous talks about it, the Tupinambá appealed again to accounts of their history to remind me that they were forced out from the north seacoast area that had not been possible to consider traditionally occupied in accordance to the 231 article of the Constitution. I again showed that I knew their stories and considered their memories as valid markers of those past events, not only from their point of view but also from our understanding of memory and landscape in social sciences. However, I argued again, since the area is no longer inhabited, it becomes a weak argument considering the justification of indigenous land. I made them notice that this is because indigenous land is based on the rights over contemporary practices and not historical restitution, and that in many ways this is an advantage for them and more acceptable for public opinion in Brazil.

I argued further that by including the area of the mangrove and the access to the fishing point I was sustaining the juridical justification of the definition of indigenous land in a strong argument that would have real chances of being maintained, even in the face of the economic, political and juridical pressures that would necessarily occur. I knew, however, that I was just trying to make a compatible agenda suitable for the identification of the indigenous land. The memories of the massacres that occurred in the past to expel the Tupinambá of Olivença from this area of the seacoast would not vanish. For this reason, I insisted on the fact that this was the only possible political and juridical alternative at the moment.

After finishing the meetings with the Tupinambá in July 2005 I went to Funai in Brasilia to finish the map and make a presentation of my arguments to the chief of the Department of Land Affairs. There, predictably, tense moments arose in regard to the inverse situation: I was asked how I could account for such an extensive area in a region like the Atlantic coast of Brazil. Before this official agency I had to rely heavily on how my data would justify the four principles that define indigenous land in the 1988 Constitution.

In both cases – the meetings with the Tupinambá and the one with Funai in Brasilia – I was reaching an agreement which depended solely on an argument in which anthropological and constitutional issues had been fixed to make a compatible relationship feasible. This also implied listening to and incorporating different results of our conversations in the field. After the meetings with the Tupinambá I always tried to fix the borders of the indigenous land taking into account their requests. After the meeting with Funai in July 2005, I was able to include in my arguments issues that could be important from the perspective of the government and political pressures, such as to rely solely on technical arguments.

CLOSING REMARKS

In this article I showed that the case of the legal definition of indigenous land in the 1988 Constitution of Brazil is paradigmatic in clarifying the idea that the construction of public categories can no longer be considered external to debates in the social sciences. The definition of indigenous land given by the Constitution was legislated upon and debated among indigenous leaders, anthropologists, jurists and public opinion, linking issues of national and international politics to academic agendas and to the defence of equal social and human rights. Secondly, I argued that we need to cling to the contemporary way of doing ethnography through connecting, on the one hand, how people live in-the-world to a more abstract regional and comparative thinking, and, on the other hand, by contextualizing this experience of living within ideas developed in the public sphere: for instance, understanding how public opinion and ethnic politics face indigenous rights and how people construct meanings from their own sites of understanding in the world. This creates a state of affairs where, as Ramos put it, the anthropologists activism is not secluded from the academic interests of the profession. Quite the opposite, one nourishes the other (Ramos 2003: 113). It is in this perspective that the work of the anthropologist can be defined as the search for compatible agendas strongly sustained in ethnographical approaches.

This type of research cannot be defined as applied anthropology, currently understood as work done outside academic departments of anthropology, by people who make direct use of an anthropological training in policy- or practice-oriented work (Sillitoe 2006: 1-2). However, as a result from many different circumstances of the post-colonial world, we know that nowadays public policy-makers are more interested in listening to what anthropologists have to say than before: they are willing to have insights coming from bottom-up approaches in development policies and to include traditional knowledge in development projects (Sillitoe 2006: 10; Mosse and Lewis 2006). Reflections on applied anthropology, mainly in the field of development, are also increasingly critical of definitions in which they see themselves acting as mediators in a situation previously defined as the interface between two different sides. As Mosse and Lewis put it:

The key concept of interface (between different social or life worlds, knowledge and power) itself involves an unhelpful compartmentalisation of identities and may be an increasingly inadequate metaphor for the various types of exchange, strategic adaptations, or translations contained within development interventions (Mosse and Lewis 2006: 10).

We can thus consider that the argument for working towards compatible agendas can be an alternative to the concept of interface and be of interest in a broader reflection on how public and academic knowledge are intertwined. In situations such as the identification of indigenous land, the engagement of an anthropologist in advocacy tends to be a continuing result of their experience in academic fieldwork, confirming, as Alcida Rita Ramos also argues, the merit of blending anthropological activism with the quest for knowledge (Ramos 2003: 115).

In this article, in sum, I presented the arguments and negotiations of meanings in the definition of the seacoast limits of the indigenous land of the Tupinambá of Olivença in order to make clear that ethnography, as situated knowledge, is the most suitable way of dealing with categories pre-defined in the public arena, because it allows us to negotiate from different perspectives seeking and constantly working, in this way, for a compatible peace.

REFERENCES

AGIER, Michel, and M. Rosario G. de CARVALHO, 1994, Nation, race, culture: les mouvements noirs et indiens au Brésil, Cahiers des Amériques Latines, 17: 107-124.

ALBERT, Bruce, 1997, Ethnographic situation and ethnic movements: notes on post-Malinowskian fieldwork, Critique of Anthropology, 17 (1): 53-65.

ALMEIDA, Miguel Vale de, 2004, An Earth-Colored Sea: Race, Culture and the Politics of Identity in the Post-Colonial Portuguese-Speaking World. Oxford and New York, Berghahn Books.

BAINES, Stephan Grant, 1997, Tendências Recentes na Política Indigenista no Brasil, na Austrália e no Canadá. Brasília, Departamento de Antropologia da Universidade de Brasília (Série Antropologia, 224).

BARTH, Fredrik, 1998 [1969], Introduction, in Fredrik Barth (ed.), Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture Difference. Illinois, Waveland Press, 9-38.

BELAUNDE, Luisa Elvira, 2000, The convivial self and the fear of anger amongst the Airo-Pai of Amazonian Peru, in Joanna Overing and Alan Passes (eds.), The Anthropology of Love and Anger: The Aesthetics of Conviviality in Native Amazonia. London and New York, Routledge, 209-220.

, 2001, Viviendo Bien: Género y Fertilidad entre los Airo-Pai de la Amazonía Peruana. Lima, Centro Amazónico de Antropología y Aplicación Práctica.

BROWN, Michael, 1993, Facing the state, facing the world: Amazonias native leaders and the new politics of identity, LHomme: la remonté de lAmazone – anthropologie et histoire des sociétés Amazoniennes, XX (126-128): 307-326.

CARSTEN, Janet, 1995, The substance of kinship and the heat of the hearth: feeding, personhood, and relatedness among Malays in Pulau Langkawi, American Ethnologist, 22 (2): 223-241.

, 2000, Introduction, in Janet Carsten (ed.), Cultures of Relatedness: New Approaches to the Study of Kinship. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1-36.

CONKLIN, Beth A., 1995, Thus are our bodies, thus was our custom: mortuary cannibalism in an Amazonian society, American Ethnologist, 22 (1): 75-101.

CONKLIN, Beth A., and Laura R. GRAHAM, 1995, The shifting middle ground: Amazonian Indians and eco-politics, American Anthropologist, 97 (4): 695-710.

CUNHA, Manuela Carneiro da, 1986 [1983], Parecer sobre os critérios de identidade étnica, in Manuela Carneiro da Cunha, Antropologia do Brasil: Mito, História, Etnicidade. São Paulo, Brasiliense, 113-119.

FAUSTO, Carlos, 2007, Feasting on people: eating animals and humans in Amazonia, Current Anthropology, 48 (4): 497-530.

FREIRE, Germán, 2003, Tradition, change and land rights: land use and territorial strategies among the Piaroa, Critique of Anthropology, 23 (4): 349-372.

GOLDMAN, Irving, 2004, Cubeo Hehénewa Religious Thought: Metaphysics of a Northwestern Amazonian People. New York, Columbia University Press.

GOLDMAN, Marcio, 2006, Como Funciona a Democracia: Uma Teoria Etnográfica da Política. Rio de Janeiro, 7 Letras.

GONÇALVES, Wagner, 1994, Terras de ocupação tradicional: aspectos práticos da perícia antropológica, in Orlando S. Sampaio, Lídia Luz and Cecília M. Helm (eds.), A Perícia Antropológica em Processos Judiciais. Florianópolis, UFSC, 79-87.

GOW, Peter, 1989, The perverse child: desire in a native Amazonian subsistence economy, Man, 24 (4): 567-582.

, 1991, Of Mixed Blood: Kinship and History in Peruvian Amazonia. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

HARRIS, Mark, 2000, Life on the Amazon: The Anthropology of a Brazilian Peasant Village. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

HEDICAN, Edward J., 2000, Applied Anthropology in Canada: Understanding Aboriginal Issues. Toronto, Buffalo and London, University of Toronto Press.

JACKSON, Jean, 1999, The politics of ethnographic practice in the Colombian Vaupés, Identities, 6 (2-3): 281-317.

LATOUR, Bruno, 2002. War of the Worlds: What about Peace? Chicago, Prickly Paradigm Press.

LIMA, António Carlos de Souza, 1995, Uma Grande Cerca de Paz: Poder Tutelar, Indianidade e Formação do Estado no Brasil. Petrópolis, RJ, Vozes.

LIMA, Antonio Carlos de Souza, and Henyo Trindade BARRETTO FILHO, 2005, Antropologia e identificação: os antropólogos e a definição de terras indígenas no Brasil, 1977-2002: uma apresentação, in A. C. de Souza Lima and Henyo T. Barretto Filho (eds.), Antropologia e Identificação: Os Antropólogos e a Definição de Terras Indígenas no Brasil, 1977-2002. Rio de Janeiro, Contracapa, 9-28.

MAGALHÃES, Edvard Dias (ed.), 2003a, Constituição da República do Brasil – 1988, Legislação Indigenista Brasileira e Normas Correlatas. Brasília, CGDOC / Funai, 21-30.

, (ed.), 2003b, Decreto n.º 1.775 de 08 de janeiro de 1996, Legislação Indigenista Brasileira e Normas Correlatas. Brasília, CGDOC / Funai, 146-152.

McCALLUM, Cecilia, 1999, Consuming pity: the production of death among the Cashinahua, Cultural Anthropology, 14 (4): 443-471.

, 2001, Gender and Sociality in Amazonia: How Real People are Made. Oxford, Berg.

MENDES, Artur Nobre, 2002, Introdução: reconhecimento das terras indígenas, situação atual, in Márcia Maria Gramkow (ed.), Demarcando Terras Indígenas II: Experiências e Desafios de um Projeto de Parceria. Brasília, Funai / GTZ / PPTAL, 13-22.

MOSSE, David, and David LEWIS, 2006, Theoretical approaches to brokerage and translation in development, in David Mosse and David Lewis (eds.), Brokers and Translators: The Ethnography of Aid and Agencies. Bloomfield, Kumarian Press, 1-26.

MUNN, Nancy D., 1992, The Fame of Gawa: A Symbolic Study of Value Transformation in a Massim Society (Papua New Guinea). Durham, Durham University Press.

ODWYER, Eliane Cantarino, 2005, Laudos antropológicos: pesquisa aplicada ou exercício profissional da disciplina?, in Ilka Boaventura Leite (ed.), Laudos Periciais Antropológicos em Debate. Florianópolis, Associação Brasileira de Antropologia, 215-238.

OLIVEIRA, João Pacheco, 2002, O antropólogo como perito: entre o indianismo e o indigenismo, in Benoit de LEtoile, Federico Neiburg and Lygia Sigaud (eds.), Antropologia, Impérios e Estados Nacionais. Rio de Janeiro, Relume Dumará, 253-277.

OVERING, Joanna, and Alan PASSES, 2000, Introduction, in Joanna Overing and Alan Passes (eds.), The Anthropology of Love and Anger: The Esthetics of Conviviality in Native Amazonia. London, Routledge, 1-30.

PINA-CABRAL, João de, 1999, Trafic humain à Macao: les compatibilités équivoques de la communication interculturelle, Ethnologie Française, XXIX (2): 225-236.

RAMOS, Alcida Rita, 1995, Sanumá Memories: Yanomami Ethnography in Times of Crisis. Madison, University of Wisconsin Press.

, 1998, Indigenism: Ethnic Politics in Brazil. Madison, The University of Wisconsin Press.

, 2002, Cutting through state and class: sources and strategies of self-representation in Latin America, in E. Jean Jackson and Kay B. Warren (eds.), Indigenous Movements, Self-Representation, and the State in Latin America. Austin, University of Texas Press, 251-279.

, 2003, Advocacy rhymes with anthropology, Social Analysis, 47 (1): 110-115.

RICHARDS, Audry, 1969 [1939], Land, Labour and Diet in Northern Rhodesia: An Economic Study of the Bemba Tribe. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

RIVAL, Laura, 1998, Androgynous parents and guest children: the Huaorani couvade, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (n.s.), 4: 619-642.

RIVIÈRE, Peter, 1984, Individual and Society in Guiana: A Comparative Study of Amerindian Social Organization. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

SANTILLI, Paulo José Brando, 2001, Usos da terra, fusos da lei: o caso Makuxi, in Regina Reys Novaes and Roberto Kant de Lima (eds.), Antropologia e Direitos Humanos. Niterói and Rio de Janeiro, EdUFF.

SANTOS, Sílvio Coelho dos, 1995, O direito dos indígenas no Brasil, in Aracy Lopes da Silva and Luís Donisete Benzi Grupioni (eds.), A Temática Indígena na Escola: Novos Subsídios para Professores de 1.º e 2.º Graus. Brasília, MEC / MARI / UNESCO, 87-108.

SEEGER, Anthony, Eduardo VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, and Roberto DA MATTA, 1979, A construção da pessoa nas sociedades indígenas brasileiras, Boletim do Museu Nacional, 32: 2-19.

SILLITOE, Paul, 2006, The search for relevance: a brief history of applied anthropology, History and Anthropology, 17 (1): 1-19.

SISKIN, Janet, 1973, To Hunt in the Morning. London, Oxford and New York, Oxford University Press.

TURNER, Terence, 1995, Social body and embodied subject: bodiliness, subjectivity, and sociality among the Kayapo, Cultural Anthropology, 10 (2): 143-170.

UNITED NATIONS, 2007, United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, available at the Official Document System of the United Nations, <http://documents.un. org/mother.asp>, ref. A / RES / 61 / 295.

VIEGAS, Susana de Matos, 2000, Depois da diferença: identificações étnicas e de classe num contexto indígena no Sul da Bahia, in Boaventura de Sousa Santos, Amélia Cohn e Aspásia Camargo (eds.), O Diálogo dos 500 Anos: Brasil-Portugal entre o Passado e o Futuro. Rio de Janeiro, EMC Edições, 261-283.

, 2003, Eating with your favourite mother: time and sociality in a South Amerindian community (South of Bahia / Brazil), Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 9 (1): 21-37.

VIEGAS, Susana de Matos, 2006, Nojo, prazer e persistência: beber fermentado entre os Tupinambá de Olivença (Bahia), in John Monteiro (ed.), Dossier História dos Índios, Revista de História, 154: 151-188. [ Links ]

, 2007, Terra Calada: Os Tupinambá na Mata Atlântica do Sul da Bahia. Rio de Janeiro, 7 Letras.

, 2008, Mulheres transitivas: hegemonias de género em processos de mudança entre os Tupinambá de Olivença (Brasil), in Manuel Villaverde Cabral, Karin Wall, Filipe Carreira da Silva and Sofia Aboim (eds.), Itinerários: A Investigação nos 25 Anos do ICS. Lisbon, Imprensa de Ciências Sociais, 623-640.

, 2009, Can anthropology make valid generalizations? Feelings of belonging in the Brazilian Atlantic forest, Social Analysis, 53 (2): 147-162.

VIEGAS, Susana de Matos, Juliana Melo, e Jorge Paula, 2009, Resumo do relatório circunstanciado de delimitação da terra indígena tupinambá de Olivença, Diário Oficial da União, vol. 1, issue 74, April 20, 52-57. [ Links ]

VILAÇA, Aparecida, 1998, Fazendo corpos: reflexões sobre morte e canibalismo entre os Wari à luz do perspectivismo, Revista de Antropologia, 41 (1): 9-67. [ Links ]

, 2005, Chronically unstable bodies: reflections on Amazonian corporalities, Journal of the Anthropological Royal Institute (n. s.), 11: 445-464.

VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, Eduardo, 1998, Cosmological deixis and Amerindian perspectivism, Journal of the Anthropological Royal Institute (n.s.), 4: 469-483.

, in press, Dinâmica da equivocidade objectiva (comentário), in Carlos Fausto and John Monteiro (eds.), Tempos Índios: Narrativas do Novo Mundo. Lisbon, Assírio e Alvim.

NOTAS

[1] The subject evolved from one of the proposals for debate in Ethnografeast III, where a first version of the argument of this article was presented (see introduction to this dossier).

[2] This article is based on fieldwork I carried out in Southern Bahia, Brazil, from August 1997 to August 1998, supported by the Foundation for Science and Technology, Portugal, through research reference PRAXIS PCSH / P / ANT / 42 / 96, and in 2003-2008 research reference POCI / ANT / 61198 / 2004. This last period was also funded by the National Indian Foundation (Funai) and UNESCO (research reference SA-12333 / 2004; 914BRA3018). I am most grateful for the comments and insights made by reviewers of the journal to the previews version of this article.

[3] The same article of DRIP establishes in line 3 that, States shall give legal recognition and protection to these lands, territories and resources. Such recognition shall be conducted with due respect to the customs, traditions and land tenure systems of the indigenous peoples concerned (United Nations 2007, Article 26).

[4] The following phases are: Declaration (the responsibility of the Ministry of Justice), demarcation (the responsibility of Funai), homologation (signed by the President of the Federal State) and register (Funai) (cf. Mendes 2002: 17). When the process becomes open to juridical contestation, the government will uphold its arguments using information from the anthropological study, but anthropologists do not intervene directly.

[5] It must be emphasised that indigenous land only includes the rights of use and not ownership, which will be given to the Federal State. This means the register of indigenous land does guarantee the right for indigenous people to inhabit the land, but neither to sell it nor use it as any kind of guarantee for commercial transactions individually or collectively (Santos 1995: 87).

[6] In contrast to what happened in the United States of America or in British Columbia, it should be noted that indigenous movements in Brazil empowered the term índio (Indian) on their own behalf and thus do not consider it as an expression of colonial oppression.

[7] Even before the Constitution, anthropologists were consulted to give a professional opinion on issues such as the definition of ethnic identity that resulted in the famous article of Manuela Carneiro da Cunha (1986 [1983]). This article has been influent both in the academia and in public indigenous policies on the self-determination rights of indigenous people in Brazil until the present. The theoretical perspectives adopted by Cunha are strongly influenced by Fredrik Barths 1960 concept of ethnic identity as boundaries constituted by the people and recognized by others (Barth 1998 [1969]).

[8] Especially with a cooperation programme financed by the World Bank and several European countries in 1994 – Projeto Integrado de Proteção às Populações e Terras Indígenas da Amazônia Legal (PPTAL) – a G7 funded initiative to demarcate indigenous lands in the Brazilian Amazon.

[9] The Act 1.775, January 8th of 1996, in its Article 2 explicitly considers the collaboration of anthropologists necessary in the identification of indigenous lands in Brazil: The demarcation of lands traditionally occupied by Indians will be supported by research carried out by a properly accredited anthropologist, who will put together an anthropological identification report within a deadline determined by the responsible entity of the federal organism in charge of the Department of Indigenous Affairs (cit. in Magalhães 2003b: 146).

[10] For a more detailed ethnography of social and political movements in Ilhéus see Almeida (2004), Viegas (2000) and Goldman (2006). I also carried out some interviews with indigenous people, landowners and with people in different administrative and political positions of responsibility in the region. I taped around fifty of those interviews, but during that year the fieldwork material resulted mostly from daily informal conversations and observation of daily life: from the interaction in a house at night, to baths, gardening, making manioc flour, taking care of children, attending festivities and so on and so forth.

[11] Because I am a foreigner (Portuguese), the team for the identification of the Tupinambá of Olivença indigenous land also included another anthropologist from Funai who is Brazilian. Funai had to make a juridical consultation to see what could be done about the fact of having a foreign anthropologist coordinating the process.

[12] As mediators, the Tupinambá women revealed special skills, because on average they have a higher educational level and experience of dealing with urban people and life (cf. Viegas 2007: 170-175, 2008). For the Tupinambá of Olivença this type of leadership is different from what they considered traditional leadership, based on dynamics of kinship (cf. Viegas 2007: 173-174).

[13] It would be impossible to mention here all ethnographies devoted to the subject, but reference must be made to the classic works by Audry Richards (1969 [1939]), and Nancy Munn (1992: 49-73) among the Gawa of Papua New Guinea. In these cases, as in many ethnographies on Amazonia, what is noteworthy is the moral and emotional code involved in the act of giving, receiving and / or sharing food (Siskin 1973: 9; Gow 1991; Belaunde 2000: 209, 2001: 182; McCallum 1999).