The decline

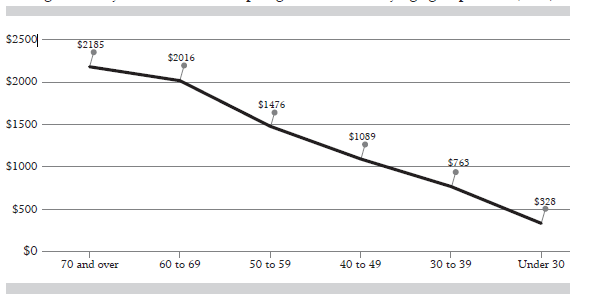

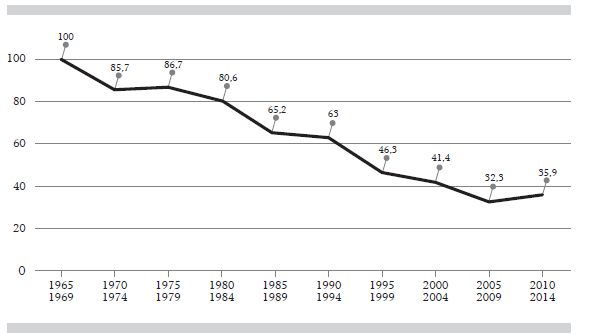

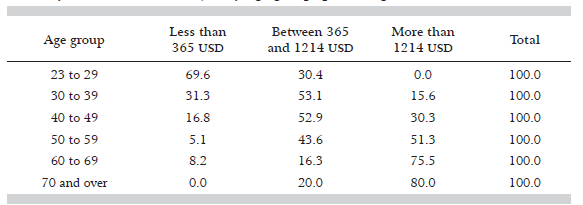

Employment1 conditions for anthropologists2 in Mexico have worsened considerably throughout the last few decades, according to a survey conducted in 2016.3 Certain key indicators reveal a wide gap in working conditions from one generation to the next. Figure 1 shows the decrease in average income for younger cohorts with respect to older ones.

Source: own analysis based on Survey on Professional Practice and Working Conditions of Anthropologists in Mexico (CIEPA-CEAS 2016).4

Figure 1 Average monthly income for anthropologists in Mexico by age group, 2016 (USD)

The income drop is notorious. In 2016 anthropologists over the age of 60 earned an average of 2000 USD5 a month,6 whereas those between ages 30 and 39 averaged 763 USD, and those under 30 averaged only 328 USD. Incomes for the youngest anthropologists are lower than those of high school graduates, and in some cases even lower than those of unskilled workers. It is not surprising that older anthropologists have higher incomes. After all, they have obtained degrees, qualifications, experience, contacts, opportunities, seniority and other assets, all of which lead to better wages. Nevertheless, it is striking to see such a wide margin between age groups: anthropologists over the age of 70 make almost seven times as much as their youngest colleagues. They also make twice as much as those between ages 40 and 49.

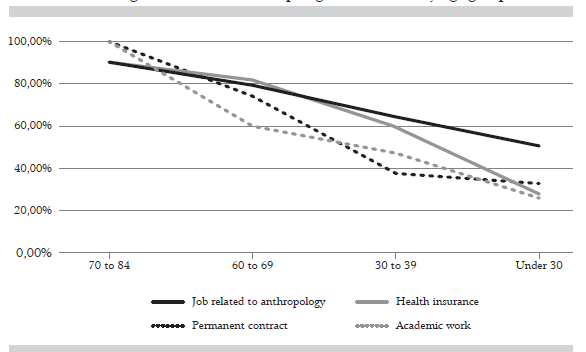

The youngest anthropologists in Mexico also face more precarious working conditions than their elders. Figure 2 shows how the situation has worsened from one generation to the next.

Source: own analysis based on Survey on Professional Practice and Working Conditions of Anthropologists in Mexico (CIEPA-CEAS 2016).

Figure 2 Decline in working conditions for anthropologists in Mexico by age group, 2016.

Among working anthropologists under the age of 30, only about half (51.1%) have jobs that relate to their field. This points to how difficult it can be for them to find work where they actually apply the skills acquired in training. In contrast, 78.9% of anthropologists between ages 50 and 69, and 90% of those over 70, have jobs directly related to their field.

Job stability is one of the main factors that distinguish precarious from decent employment. In this crucial aspect, younger cohorts face a complicated panorama: only 37.9% of working anthropologists between ages 30 and 49, and 32.6% of those under 30, have indefinite contracts. In other words, only about a third of working anthropologists under 50 have permanent employment; the remaining two thirds hold temporary jobs. Meanwhile, older anthropologists face very different circumstances: 74% of those between ages 50 and 69, and 100% of those over 70, have permanent employment. Additionally, among working anthropologists under 30, only 28.3% have health insurance and a mere 26% work in academia.

These figures reveal a sharp contrast between different age groups. Among anthropologists aged 50 and over, most have access to stable jobs in academia, with benefits and decent salaries - a monthly average of 1476 USD for those between 50 and 59, and over 2000 USD a month for those aged 60 and over. Meanwhile, most anthropologists under 50 do not work in academia or have stable employment, and average low to very-low incomes for professionals in Mexico - 1089 USD for those between ages 40 and 49, 763 USD for those between 30 and 39, and 328 USD for those under 30.

What has caused such a steep drop in wages? How can this decline in working conditions be framed and understood? What follows is an attempt to answer these questions.

Crisis of success and neoliberal policies: job market dynamics for anthropology in Mexico

Precarity and insecurity in the job market are not exclusive to anthropology. This problem affects most young professionals in Mexico and several other countries (Mora and Oliveira 2011, 2014; Oliveira 2009). This phenomenon relates to demographic changes, overcrowding in higher education and a general devaluation of educational credentials, as well as to certain neoliberal policies of job market flexibilization that have stagnated the creation of stable jobs with good working conditions.

In the case of Mexico, these unfavorable career prospects also relate to specific public policies in education, science and technology that have catered to market dynamics, as well as to a stratification of academic personnel encouraged by the National System of Researchers (SNI, for its Spanish acronym) and other systems that incentivize and prioritize individual productivity (Krotz 2011). Furthermore, these contextual factors, which are common to a number of fields, are accentuated by issues that specifically relate to professional anthropology, namely the popularization and expansion of the field throughout the last five decades.

Fifty years ago, there were no more than a few dozen anthropologists in Mexico. Anthropology was a fairly unusual occupation, practiced mostly by middle and upper-class professionals who studied in Mexico City. Nowadays, it is a popular field of work that draws thousands of candidates from a wide range of social backgrounds, and there are numerous academic programs throughout the country.

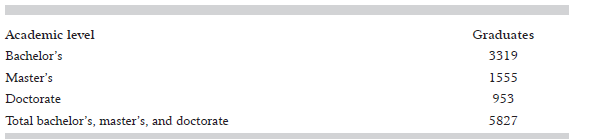

Anthropology in Mexico is undergoing a crisis enabled by its own success - it attracted thousands of students but has recently failed to create enough job opportunities for young graduates. This crisis can be explained, firstly, by the exponential growth in the number of anthropologists in Mexico 7 over the last 50 years. The present century in particular has witnessed an astonishing boom. Between 2000 and 2017, at least 5827 anthropologists completed professional degrees: 3319 bachelor’s graduates, 1555 master’s graduates and 953 doctorate graduates, as shown in the following table 1.8

Table 1 Anthropology graduates in Mexico between 2000 and 2017 at bachelor’s, master’s and doctorate levels.

Source: own analysis based on Historical Catalogue of Theses on Social Anthropology in Mexico (RedMIFA 2018).9

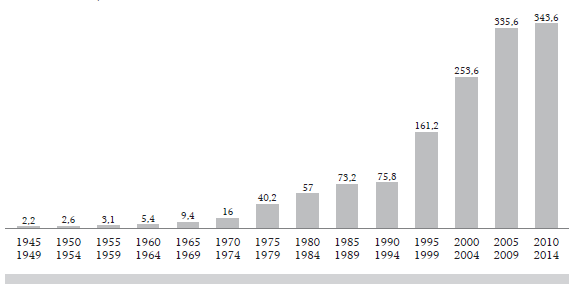

Between 2000 and 2017 at least 3319 anthropologists completed an undergraduate degree, and 1555 completed a master’s degree, from one of 22 different academic programs. There are also eight anthropology doctorate programs in Mexico, which certified 953 PhD’s in that same time period. (Figure 3) In the 1950’s, only one or two anthropologists graduated every year; now more than 300 do so. According to the Catalogue, between 2000 and 2017, an average of 324 anthropologists completed professional degrees each year (185 bachelor’s, 86 master’s and 53 doctorates).

Source: own analysis based on Historical Catalogue of Theses on Social Anthropology in Mexico (RedMIFA 2018).

Figure 3 Yearly average of anthropology graduates in Mexico (quinquennial periods from 1945 to 2014)

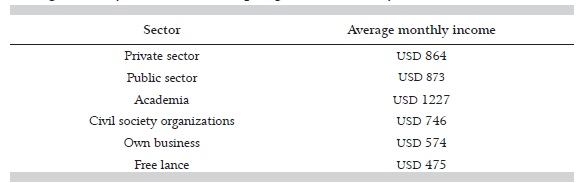

Most anthropologists in the country do not have stable jobs. From those who are employed, only 46.2% have indefinite contracts; more than half (53.8%) have no job security and depend on either renewing temporary contracts, signing new contracts, taking part in new projects or securing teaching positions for the following academic term. (figure 4) There is a clear trend towards job insecurity for those who graduated in the past few decades, which itself points to a nationwide problem of employment instability (Mancini 2017).

Source: own analysis based on Survey on Professional Practice and Working Conditions of Anthropologists in Mexico (CIEPA-CEAS 2016).

Figure 4 Percentage of anthropologists with indefinite contracts in 2016, relative to when they graduated.

Among the anthropologists who completed the survey, those who graduated between 1965 and 1969 all have permanent employment. But this number has consistently decreased: only 32.3% of those who graduated between 2005 and 2009, and 35.9% of those who graduated between 2010 and 2014, have this kind of security. Indefinite contracts were common for anthropologists who graduated between the 1940’s and the first half of the 1980’s; they became less so in the second half of the 20thcentury and are altogether rare for anthropologists who have graduated in the current century. Very few under the age of 40 have stable employment: only 29.7% have indefinite contracts, against 60.4% of their colleagues between ages 40 and 59, and 86% of those aged 60 and over.

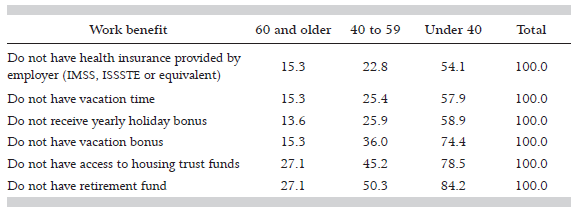

This precarity for young anthropologists in Mexico also means that many of them lack even the most basic work benefits, as shown in the table 2.

Table 2 Percentage of anthropologists without work benefits in their current job, by age group.

Source: own analysis based on Survey on Professional Practice and Working Conditions of Anthropologists in Mexico (CIEPA-CEAS 2016).

Most anthropologists under the age of 40 work without essential benefits: 54.1% do not have health insurance provided by their employer, 57.9% have no vacation time and 58.9% do not receive a yearly holiday bonus. The situation is worse when it comes to less widespread benefits: 74.4% have no vacation bonus, 78.5% have no access to housing trust funds, and 84.2% have no retirement fund.

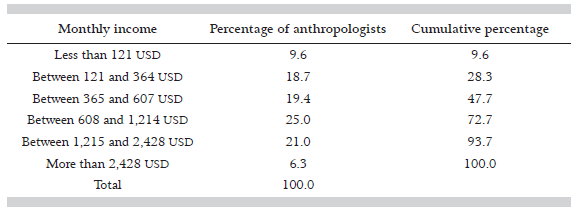

This data suggests that professional anthropology is highly stratified. Only a few enjoy full benefits, some have basic benefits, and others have no benefits at all. This is partly related to age, as shown in the data on anthropologists’ incomes. The Survey shows that the average income for anthropologists in 2016 was 990 USD. However, an average monthly income of 990 USD is one thing; exactly how much each person makes is quite another. This stratification, which is an expression of the social inequality that surrounds it, can be observed in table 3.

Table 3 Monthly incomes of anthropologists in Mexico, 2016.

Source: own analyisis based on Survey on Professional Practice and Working Conditions of Anthropologists in Mexico (CIEPA-CEAS 2016).

There are three large groups. The first, which represents 28.3% of working anthropologists, averages a monthly income of under 364 USD. This is less than the wages of many unskilled or administrative workers in the country (in 2016, the average monthly income for high school graduates in Mexico was 342 USD). The second group, which represents 44.4% of working anthropologists, earns between 365 and 1214 USD. This is similar to the average earnings among college graduates in Mexico (599 USD).10 Lastly, the third group, which represents 27.3% of working anthropologists, averages a monthly income of over 1214 USD. This is higher than the average among bachelor’s, master’s and doctorate graduates. Moreover, there is a small segment (6.3% of working anthropologists) with a monthly income of over 2428 USD. A good portion of those with the highest incomes work in academia and belong to the SNI. Grants awarded by the SNI when the Survey was carried out ranged from 363 to 1821 USD a month, in addition to the salaries these anthropologists received from their universities.

Incomes vary considerably from one sector to another. Naturally, anthropologists in academia have much higher incomes than the rest - a monthly average of 1277 USD. Below are anthropologists in the public sector (873 USD), the private sector (864 USD) and civil society organizations (746 USD). Incomes are notoriously low for those who own a private business (574 USD) or those who work freelance (475 USD). This suggests that the alleged advantages of entrepreneurship and flexible careers with no permanent jobs and employers might be questionable, to say the least. More than anything, starting a business or working freelance in anthropology seem to reflect uncertainty, precarity and a lack of more gainful career opportunities. People who work in these sectors face the harshest conditions: according to the Survey, out of 45 freelance anthropologists only three earn more than 1214 USD; out of 20 who started their own businesses only three earn more than 1214 USD. (table 4) 11

Table 4 Average monthly income of anthropologists in Mexico by sector, 2016 (USD).

Source: own analysis based on Survey on Professional Practice and Working Conditions of Anthropologists in Mexico (CIEPA-CEAS 2016).

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, young anthropologists have the lowest incomes. According to the Survey, there is a strong correlation between age and income - as professionals get older, their incomes get higher.

In most cases, younger anthropologists have lower salaries than their older colleagues. Monthly incomes for anthropologists under 40 are extremely low: 42.4% earn less than 365 USD, and 46.5% earn between 365 and 1214 USD; only 11.1% earn more than 1214 USD and none earn more than 2429 USD. Conditions are very different for anthropologists aged 60 and over: only 6.8% earn less than 365 USD and 16.7% earn between 365 and 1214 USD, while over three quarters (76.3%) earn more than 1214 USD. Moreover, a third of them (32.7%) earn more than 2428 USD. (table 5).

Table 5 Monthly incomes in current job by age group (percentages).

Source: own analysis based on Survey on Professional Practice and Working Conditions of Anthropologists in Mexico (CIEPA-CEAS 2016)

Incomes for anthropologists under the age of 30 are also notoriously low: 69.6% earn less than 365 USD a month, and 30.4% earn between 365 and 1214 USD. None earn more than that. It is true that many of these young anthropologists are still studying, and in many cases still live with their parents, but such low wages make it very difficult for them to cover even their most basic expenses. More often than not, they do not earn enough to maintain a household and support a family, except in very precarious conditions. Among anthropologists between ages 30 and 40, 31.3% earn less than 365 USD a month; a little over half (53.1%) earn between 365 and 1214 USD, and only 15.6% earn more than 1214 USD. Most of them make enough to cover their own cost of living, but certainly not enough to support children, buy a home or face larger expenses (35% of anthropologists between ages 30 and 39 have economic dependents). The group between ages 40 and 49 is in a similar situation, and only slightly better off: 16.8% earn less than 365 USD, 52.9% earn between 365 and 1214 USD, and only 30.3% earn more than 1214 USD. Members of this age group are under considerable financial pressure, as 69.4% of them have dependents. The group between ages 50 and 59 is the first where most anthropologists can be considered high income earners by Mexican standards: 51.3% earn more than 1214 USD a month, which is also the case for 75.5% of anthropologists between ages 60 and 69, and for 80% of those over 70. Anthropology in Mexico seems to be a profession where the older generations have relatively high incomes. Those aged 60 and over average over 2000 USD a month. Very high salaries, comparable to those of doctors, lawyers, architects or business managers are rare, but most senior anthropologists have managed to procure decent incomes. This relates to the aforementioned “crisis of success” that anthropology underwent in the last decades of the 20thcentury, as well as to the fact that, during that same time period, many were able to secure permanent jobs in the public sector and, most importantly, in academia. The success was not only financial. Anthropology in Mexico has gained academic prestige and is now established as an attractive career option for younger generations. Paradoxically, this has led to an accelerated growth in the number of anthropologists, who are valuable for their contributions to solving a wide range of social issues in Mexico but have considerably less employment opportunities now than in previous years.

The key question here is whether younger generations of anthropologists may in time be able to secure the kind of income that older generations have today. As desirable as that would be, there are signs that it will not happen automatically, partly because older generations tend to defer retirement as much as possible in order to maintain higher salaries, which are guaranteed while they remain active. Older anthropologists face a considerable income cut upon retirement, especially if they rely entirely on the pensions granted by the Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers (ISSSTE, for its Spanish acronym), which are capped at around 1300 USD a month. Deferring retirement delays generational turnover and makes it difficult for new cohorts to access permanent, well-paid positions. At the same time, one must also account for the effects of certain disadvantages among age groups, which are present from the start.

The following table 6 and 7 shows incomes for different age groups in their first job after completing undergraduate studies. It is interesting to see incomes for different age groups in similar stages of their careers, as opposed to comparing anthropologists in different stages (for example, a 25 years old college graduate and a 60 years old PhD with over 30 years’ experience in the field).

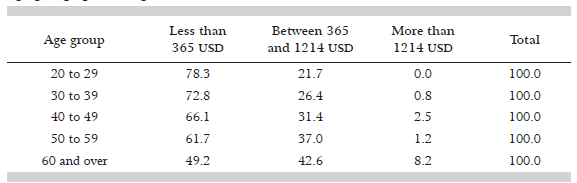

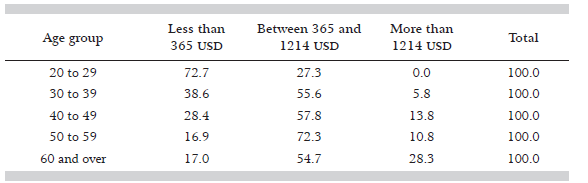

Table 6 Monthly incomes for first employment after completing undergraduate studies, by age group (percentages).

Source: own analysis based on Survey on Professional Practice and Working Conditions of Anthropologists in Mexico (CIEPA-CEAS 2016).

In their first job after completing a bachelor’s degree, younger anthropologists clearly had lower incomes than older ones: 78.3% of those between the ages of 20 and 29, and 72.8% of those between ages 30 and 39, had incomes of less than 365 USD a month. The percentage is much lower (49.2%) for anthropologists aged 60 and over. It is also true that, among those under 40, incomes of more than 1214 USD a month were exceptionally rare - only two people out of 352 (0.6%). The group aged 60 and over had the best incomes right after undergraduate studies: only 49.2% had incomes below 365 USD; 42.6% earned between 365 and 1214 USD, and even 8.2% earned above 1214 USD. These people were all born before 1957 and started their careers between the 1960’s and the beginning of the 1980’s, when there were fewer anthropologists in Mexico, before the outset of major economic crises and the implementation of neoliberal policies.

Table 7 Monthly incomes for first employment after completing postgraduate studies, by age group.

Source: own analysis based on Survey on Professional Practice and Working Conditions of Anthropologists in Mexico (CIEPA-CEAS 2016).

In their first job after obtaining postgraduate degrees, the group aged 60 and over had, once again, the highest incomes: 28.3% earned over 1214 USD a month. Contrastingly, the youngest age group (those under 30) had comparatively very low incomes despite having completed postgraduate studies - 72.7% earned less than 365 and none earned more than 1214 USD. In other words, almost three quarters of anthropologists under the age of 30 with a postgraduate degree got jobs where they earned below 365 USD, which is less than many unskilled workers and close to the average among high school graduates. It is very difficult for young anthropologists nowadays to find well-paid jobs, even with a master’s degree.

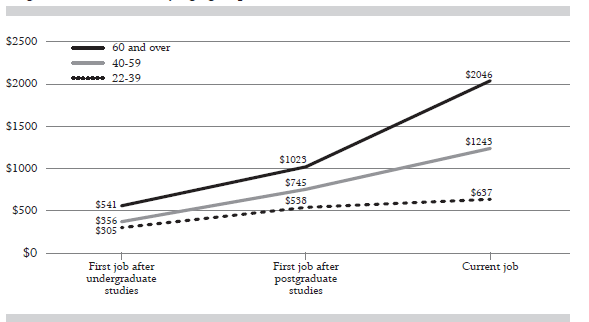

According to the data, younger generations of anthropologists have had lower incomes than previous generations throughout their careers. They started off in more precarious conditions and the disadvantages persisted, as shown in figure 5.

Source: own analysis based on Survey on Professional Practice and Working Conditions of Anthropologists in Mexico (CIEPA-CEAS 2016).

Figure 5 Development of average monthly income for anthropologists in three different stages of their careers, by age group (USD).

Each line on the graph represents one age group; the lower one is for the youngest anthropologists (23 to 39 years old). It is an almost horizontal line - they had low incomes right after their undergraduate studies, then increased them slightly after graduate school and earn slightly more in their current jobs, but have generally earned less than the older generations at each stage. Their trajectories are still very short, but they were at a disadvantage to begin with. Contrastingly, the group who are now aged 60 and over had higher incomes from the start, and have increased them considerably over time. The line is a clear upward diagonal. This means that the starting point for anthropologists of different generations has been far from even: in their first job after graduating college, the youngest (23 to 39) earned an average of only 305 USD a month, against 356 USD for the group aged between 40 and 59, and 541 USD for those aged 60 and over. The first job after graduate school also shows disparities: the group aged between 23 and 29 earned 538 USD a month, against 745 USD for those aged between 40 and 59, and 1023 USD for those aged 60 and over. Each cohort increased their incomes with time, but the youngest started off with disadvantages that were never fully surmounted. In other words, the gap is not narrowing; it will most likely remain as it is or widen over time.

Precarious working conditions and the diversification of anthropological practice

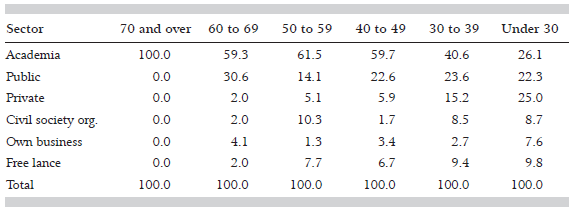

There is a strong tendency towards diversification in Mexican anthropology. For a long time, the majority of professionals in the field worked in academia. But the situation has changed for new generations, who work in many different sectors and have to seek alternative employment opportunities. Table 8 shows how employment in academia has diminished, while more are working in the private sector, civil society organizations, in their own businesses or as freelancers.

Table 8 Sectoral distribution of employment for anthropologists by age group, 2016 (percentages).

Source: own analysis based on Survey on Professional Practice and Working Conditions of Anthropologists in Mexico (CIEPA-CEAS 2016).

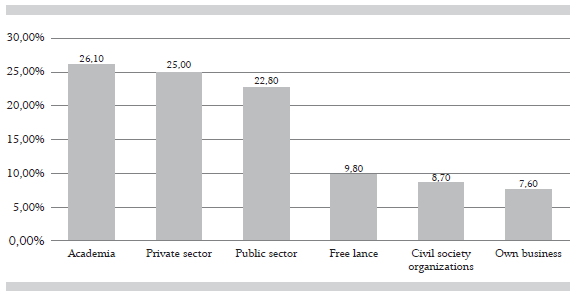

100% of anthropologists aged 70 and over, and around 60% of those between 40 and 69, are employed in academia, making it the most popular sector for professionals over 40. Contrastingly, only 40.6% of those between ages 30 and 39, and 26.1% of those under 30 work in academia. The diversity of jobs for anthropologists under 30 is shown in figure 6.

Source: own analysis based on Survey on Professional Practice and Working Conditions of Anthropologists in Mexico (CIEPA-CEAS 2016).

Figure 6 Sectoral distribution of anthropologists between the ages of 23 and 29, 2016.

Only around a fourth of anthropologists under 30 work in academia, 22.8% of them work in the public sector and the rest work in a wide range of fields, where they often face tasks they are not trained for. It is striking that over half of them (51.1%) are employed in areas typically unrelated to classical anthropological work: 25% in the private sector, 9.8% as independent freelancers, 8.7% in civil society organizations and 7.6% in their own businesses. Until about 20 years ago, freelance anthropologists were exceptionally rare. Since the end of the 20thcentury this sector has expanded: the Survey reported 45 freelance anthropologists (7.9% of those employed), two thirds of them under the age of 40. Their most popular work areas are surveys and interviews (28.9%), editing and proofreading (15.6%), translating (13.3%) and transcribing (8.9%).

It is important to add that only 48.9% of anthropologists under the age of 30 have jobs related to anthropology. In light of this, it seems fair to venture that a substantial portion of them are not satisfied with their profession, either because their work is not related to their field, or because they work in sectors other than academia. A good portion of young Mexican anthropologists are forced to renounce their interests and academic aspirations to take jobs where their formal training is not applicable, either because the work is not related to anthropology or because it involves a specific kind of applied anthropology that is not taught in classrooms. Thus begins a complex process of adaptation - young anthropologists are forced to develop different skills and adjust ethically and ideologically to tasks that are often frowned upon in academia. An employee at a consulting agency specializing in market research argues that this ethical and ideological conundrum is stronger for those who work in private companies:

“First I said ‘What am I going to do with all my ideological baggage if I take this job?’ And the first thing X said to me was ‘Hey, you have this baggage working against you and, I don’t know, it might affect your development here’. So, the only thing I could reply was that work is work; that what I cared about was being ethical. I could try to be ethical in what I thought, within myself, from anthropology; I could try to be transparent and show things as they are. And that’s what I try to do here. I’m not just trying to lure customers with half-truths. I tell things as they are, and that’s it.” 12

As far as I have been able to establish from several interviews with young freelance anthropologists who work for consulting firms and civil society organizations, this adjustment does not necessarily mean they relinquish their convictions. Often, they explore different ways of reconciling their need of a job and their aspiration to be consistent with an anthropological ethos: they try to respect the ethical codes of their employers while participating in other anthropological activities on the side. Young anthropologists can inventively adapt to a professional life outside academia. This adaptation is not only a result of employment instability, it is the expression of novel efforts to transform the practice of anthropology within different contexts.

Audit culture and the paradox of the academization of Mexican anthropology

Paradoxically, an important consequence of the lack of decent employment opportunities in academia as well as in other fields is, precisely, the tendency towards academization in Mexican anthropology! This contradiction is due both to the deterioration of anthropologists’ working conditions and to the phenomenon of the explosion of quantification and ranking devices that experts have called audit society (Power 1994 and 1997), audit culture (Shore and Wright 2015 and 2024) and metric society (Mau 2019).

In Mexico, anthropologists have responded to the competition and rankings characteristic of the audit culture by increasing their years of academic training. This has driven the trend towards the academization of anthropology. Juan Luis Sariego argued that the academization of anthropological formation consists in prioritizing the conceptual and historical aspects of the discipline, which can be useful in education and research, in lieu of teaching practical and methodological skills for problem solving and applied anthropology (Sariego 2007). This academization is related to strategies used in research and education, and to the creation of the SNI, which has encouraged individual productivity through grants and other incentives. Thus, many anthropologists prefer to focus on rewarding work such as research, publishing and thesis advising, while areas like promotion, field work, social service, community outreach, development programs and other aspects of applied anthropology are sidelined. In short, the need to increase production rates and income within systems that encourage individual productivity has caused a disproportionate growth in academic anthropology, as well as a decline in socially and politically oriented anthropology.

One of several negative consequences of audit culture is its “classificatory effect”. Statistical classifications determine who is included and excluded and therefore shape our ideas and mold our lives (Shore and Wright 2015: 439). In the case of Mexican anthropologists this effect can be seen in their efforts to pursue post-graduate studies. Young professionals trained within this context face a job market that offers few positions in academia, alongside unattractive alternatives with low pay and poor working conditions. This explains why many try to prolong their education by attending graduate school. In the last few decades, the number of postgraduate programs has multiplied, in tandem with more opportunities to obtain grants from Conahcyt (Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías). These grants often represent a better living than anthropologists could expect from the job market. In 2016 the average monthly income for working anthropologists under the age of 30 was 328 USD, and 763 USD for those between ages 30 and 39. That same year, Conahcyt grants amounted to 544 USD a month for master’s candidates and 731 USD a month for PhD candidates. It is no surprise that many young anthropologists defer entering the job market. The prevalence of precarious work thus becomes an incentive to study postgraduate degrees, because candidates can rely on grants for several years and generally stand to improve their future income.

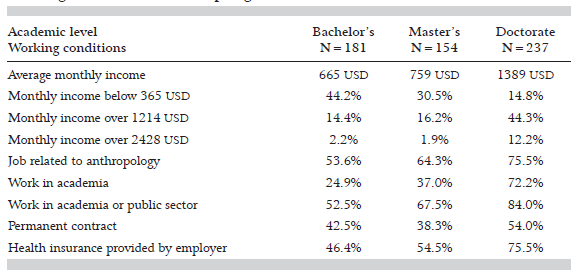

Anthropology is one of the professions with the highest proportion of postgraduate students, and anthropologists generally have notoriously high academic qualifications. Out of the thesis candidates registered in the Catalogue from 1945 to 2017, 60.6% were undergraduates, 25.8% were master’s candidates and 13.6% were doctorate candidates. The proportion of postgraduate candidates has also increased since the last century: of all the anthropology degrees awarded nationally between 1945 and 1999, 70.2% were bachelor’s, 23.4% were master’s and 6.4% were doctorates; from 2000 to 2017, 57% were bachelor’s, 26.7% were master’s and 16.3% were doctorates. The prevalence of anthropology PhD’s has also increased considerably: throughout the entire 20thcentury there were only 143 anthropologists who completed a doctorate; between 2000 and 2017 there were 953. The amount of anthropologists with master’s and doctorate degrees is also higher than average for Mexico. In 2015, out of every 100 people with higher education in Mexico, only 14 had a master’s degree and less than two (1.5) had been accepted into a PhD program. Meanwhile, out of every 100 people who completed the Survey, 27 had a master’s degree and 41 had been accepted into a PhD program. Anthropology is one of the areas with the higher proportion of master’s and doctorate graduates in the country, which means it is strongly biased towards academic work. Naturally, higher education and research institutions increasingly require master’s and PhD’s from people who want to work for them. The fact that 41% of the anthropologists who completed the Survey had been accepted into a PhD program is very revealing: anthropology is a profession that demands outstandingly high qualifications but offers few decent job opportunities outside of academia, encouraging young professionals to pursue postgraduate work. Nevertheless, a graduate degree does not guarantee a significant income boost or better working conditions. This is shown in table 9.

Table 9 Working conditions for anthropologists relative to educational attainment, 2016.

Source: own analysis based on Survey on Professional Practice and Working Conditions of Anthropologists in Mexico (CIEPA-CEAS 2016).

There are no significant differences between those with an undergraduate degree and those with a master’s; however, PhD’s are noticeably ahead of the rest. Anthropologists with an undergraduate degree earn a monthly average of 665 USD; those with a master’s average 759 USD, and PhD’s average 1389 USD. It is striking how little difference there is between those with bachelor’s and those with master’s degrees (only 94 USD). Those with master’s degrees make, on average, 14.1% more than those with a bachelor’s. The incomes of PhD’s, however, are much higher: they make more than twice as much as those with a bachelor’s degree, and 82.9% more than those with a master’s. Bachelor’s and master’s degrees are seemingly not enough to get a decent job, since 44.2% of anthropologists with bachelor’s degrees, and 30.5% of those with master’s, earn less than 365 USD a month. In contrast, only 14.8% of PhD’s earn less than that. The difference is clear even within the high-income bracket: only 14.4% of anthropologists with bachelor’s degrees, and 16.2% of those with master’s, earn more than 1214 USD a month, while 44.3% of PhD’s exceed this figure.

Aside from higher salaries, PhD’s have better working conditions: 75.5% have jobs related to anthropology, against 64.3% of those with a master’s and only 53.6% of those with a bachelor’s. They also have better chances of securing academic positions: 72.2% of PhD’s work in academia, against 37% of those with a master’s and 24.9% of those with a bachelor’s. It is also much more common for them to have permanent contracts with benefits.

In recent years higher educational attainment equals better income and working conditions. However, the differences between anthropologists with bachelor’s and master’s degrees are not very significant, and the real leap comes only for those with doctorate degrees. This suggests that the job market for anthropology in Mexico is going through a significant shift. In the 1970’s a bachelor’s degree was enough to get decent employment. Up to the 1990’s those with a master’s had good chances of getting well-paid jobs. As of this century, a master’s degree in anthropology does not guarantee a much higher income than a bachelor’s. Only those with a doctorate can expect a considerable increase in their salaries, and optimal working conditions. This is a clear example of the rapid devaluation of academic credentials. In a span of under 30 years, many of the advantages of having bachelor’s and master’s degrees have been lost. Given the swift increase in doctorate enrollment, it is likely that in a few years even PhD’s will face lower incomes. In fact, they are already having difficulties getting good jobs. The income monitor at the Universidad Iberoamericana de Puebla 13 has pointed out that, between 2012 and 2016, there was a 12% income drop for doctorate graduates with 11 to 13 years’ work experience (Moreno 2018).

New generations of anthropologists have very high academic qualifications, owing to the consolidation of several higher education and research institutions, and to the high prevalence of postgraduate candidates. Though these are the most educated anthropologists in history, they have the least job opportunities. They face a fiercely competitive job market where several hundred professionals with very high credentials have to fight over very few decent work opportunities. Those who fail to get them are forced to take precarious jobs with low incomes, poor benefits and no security, performing tasks that often have little to do with anthropology. The current generation is marked by diversity, but also by precarity, inequality and stratification. For most, the situation is far from the safety of permanent jobs with decent working conditions. It is also far from the situation of older anthropologists, who began their careers in a time of better opportunities. Work precarity has caused inequality and fragmentation in professional anthropology. The differences in salaries and working conditions between those who have a PhD and those who do not show another effect of the metric society that Mau highlights, the increase in inequality: “representations such as tables, graphs, lists or scores ultimately transform qualitative differences into quantitative inequalities” (Mau 2019: 6) Until the 1980’s there were no major asymmetries in the income of Mexican anthropologists. In the last four decades there has been a deep and growing inequality in the working conditions in the field of anthropology, with negative consequences on solidarity in this profession.

Shore and Wright have drawn attention to the perverse effects of the audit culture, which include the distrust built in the audit system and the increased stress and anxiety that ranking produces in individuals who are driven to overperform (Shore and Wright 2015). The analysis of the academization of Mexican anthropology shows another perverse effect: anthropologists are pressured to develop a practice that allows them to obtain income and comply with institutional rules, but does not necessarily translate into a benefit for society. Paradoxically, this reduces the social value of anthropology and, in the long run, may also negatively affect anthropologists’ salaries.

In conclusion, employment prospects for anthropologists in Mexico have deteriorated considerably in the last decade of the 20thcentury. As a result, new generations of anthropologists experience great difficulties in finding decent work. The majority of anthropologists under the age of 40 have ill-paid, temporary positions with no social security, which has caused diversification in anthropological practice. In contrast, the majority of anthropologists worked in academia or the public sector only a few decades ago; this is not the case for the new cohorts, where many work for private companies, civil society organizations, or as freelancers. Some anthropologists have also decided to open their own businesses, mostly in fields other than anthropology.

Despite this precarity and diversification, professional anthropological training is still geared towards academia. A considerable number of college graduates choose to pursue master’s and doctorate degrees, even though this will not necessarily guarantee a good position. It is likely that, in the near future, even a PhD will not be enough to secure well-paid, stable employment.

The decline in working conditions has paradoxical implications: on the one hand, the practice is diversified and most professionals work in fields other than academia; on the other, professional training continues to be highly academized.